Gujarat: Assembly elections, 2017

(→Urban Gujarat stays with BJP, Cong rules in agricultural pockets) |

|||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

==Urban Gujarat stays with BJP, Cong rules in agricultural pockets== | ==Urban Gujarat stays with BJP, Cong rules in agricultural pockets== | ||

| − | [http://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2017%2F12%2F19&entity=Ar01213&sk=8206534D&mode=text Urban Gujarat stays with BJP, Cong rules in agri pockets | + | [http://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2017%2F12%2F19&entity=Ar01213&sk=8206534D&mode=text Urban Gujarat stays with BJP, Cong rules in agri pockets, December 19, 2017: ''The Times of India''] |

| − | , December 19, 2017: ''The Times of India''] | + | |

Revision as of 20:22, 19 December 2017

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

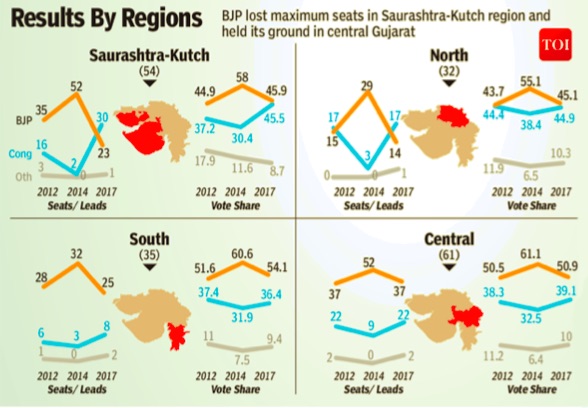

The regions

The results, region-wise

(Jai Mrug, co-author of the article, is director of VotersMood Research)

From: Nalin Mehta and Jai Mrug, Why Gujarat verdict heralds a new BJP 3.0, December 19, 2017: The Times of India

From: Nalin Mehta and Jai Mrug, Why Gujarat verdict heralds a new BJP 3.0, December 19, 2017: The Times of India

From: Nalin Mehta and Jai Mrug, Why Gujarat verdict heralds a new BJP 3.0, December 19, 2017: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

The verdict disaggregated at a subterranean level was as much about each party’s ground game & last-mile political connectivity between the message and the voter.

BJP 3.0 has managed to retain an urban support base, winning 55 of 73 urban seats.

Modi has delivered Gujarat & the extra premium he brings to BJP has been accentuated even more by this result.

While the bitter political acrimony of the Gujarat campaign - from neech politics to Aurangzeb and from Gabbar Singh Tax to Grand Stupid Idea - seemed to boil the high stakes battle down to issues of identity and economic distress, the verdict disaggregated at a subterranean level was as much about each party's ground game and last-mile political connectivity between the message and the voter. Narendra Modi has no doubt delivered Gujarat again to the BJP for its sixth successive term but the 2017 battle is the closest an electoral fight has been in Gujarat in over four decades.

This time, while Congress, fighting a prestige battle under its newly minted president Rahul Gandhi, adopted a me-too strategy on Hindu issues, the data shows that BJP, which had peaked ideologically in Gujarat, pivoted quickly under the radar to a post-ideological formulation in parts of north Gujarat and a huge swathe through central Gujarat to wrest previously Congress constituencies which tactically offset its losses in the Patidar-dominated areas of Saurashtra.

While Congress reaped the harvest of the Patidar revolt, gaining as many as 18 new Saurashtra seats (and about 30 overall) in a straight belt from Rajula at the southern tip of the peninsula to Dasada in the north, it was hit badly by its failure to retain its traditional constituencies in central Gujarat. While the caste cowboys delivered for Congress in the Hardik Patel/Alpesh Thakore heartland in Mehsana and Patan, their advances set off the making of a new ring of saffron in the adjoining areas of central Gujarat with counter-mobilisation by other castes. Incisive Congress advances into new areas were also undermined by its inability to hang on to many of its 2012 seats and that may well be the story of the election.

Gujarat was the original laboratory of Hindutava and it remains a BJP bastion but the 2017 result ironically is driven less by saffron and more by a welding together of new economic forces and social identities that have come together to create a new social matrix for the party. The only parallel we have for BJP's Gujarat ascendancy in the post-Janata phase is with the Left Front's three-decade long rule in West Bengal. Yet, both models are strikingly different. While the Left was driven by a clear rural votebank across set regions, BJP since the 1990s in Gujarat has had a dynamically evolving geographic imprint and vote base. It has kept wining elections with what we might call smart incumbency.

For example, in 1998, BJP was powered by Saurashtra-Kutch, where it bagged 53 of 58 seats. In 2002, its mandate was driven by gains in central Gujarat when it wrested the Godhra hinterland (52 of 65 seats in and around Godhra and pockets of north Gujarat) which compensated for its losses in Saurashtra that year. In 2007, this central hinterland went back to Congress and BJP pulled in neo-urban constituencies. Data shows that we may now have entered the third of BJP's avatars in Gujarat.

BJP 1.0 in Gujarat was created initially as a caste alliance against Congress's KHAM (Kshtriya, Harijan, Adivasi, Muslim) gambit in the 1980s, but in saffron clothing. BJP 2.0 saw Narendra Modi as CM consolidating the party's historic gains with his own special blend of personality politics and assertive Hindutva and turning it into the central pole of Gujarati politics.

BJP 3.0 is different. It has managed to retain an urban support base, winning 55 of 73 urban seats. It has similar support across the industrial corridor, winning 44 of 66 seats along with further and tactical gains in the south (25 seats as opposed to Congress's 10). Its southern push has been driven by upwardly mobile classes of rural tribals and the recently industrialised belts of Vapi, Valsad and Surat which created openings for a new kind of identity politics which BJP has leveraged.

Congress 2.0, driven by a renewed Rahul Gandhi may have fallen short of dethroning BJP but has made significant gains. It has succeeded in capturing the rural narrative, gaining a significant lead over BJP largely in agrarian Saurashtra and pockets of north Gujarat. The fact that the Congress charge was led by its new musketeers from outside the party - while its old satraps like Shakti Sinh Gohil, Arjun Modhwadia and Sidharth Patel lost -- shows that the gains it made with its new freelance leadership would have been far more widespread had it nurtured an organic leadership in the state over the years.

In the end, the bottomline is that Narendra Modi has delivered Gujarat and the extra premium he brings to BJP has been accentuated even more by this result. Along with the Himachal loss, Congress is now in power only in two major Indian states: Karnataka and Punjab. The results seems to continue BJP's hegemony but ironically, the signs in the rural areas of Gujarat may contain the green shots or the possibility of a Congress revival. Rahul Gandhi as Congress president will have to sustain the kind of political configuration he deployed in Gujarat while creating an election machinery on the ground that can match up to BJP's if he is to capitalize on the resentments of incumbency as we head towards 2019.

Urban Gujarat stays with BJP, Cong rules in agricultural pockets

Urban Gujarat stays with BJP, Cong rules in agri pockets, December 19, 2017: The Times of India

The rural-urban divide in Gujarat has become even sharper in these elections than five years ago. Consider this. Of the 39 urban seats, BJP won 33, Congress just six; of the 45 ‘rurban’ seats, BJP won 26 and Congress 18. But of the 98 rural seats in the state, BJP won a mere 39, Congress and its allies 55.

Interestingly, BJP’s vote share was higher than Congress’s in each of these three groups of seats, though the gap was narrowest in the rural seats and most pronounced in the purely urban ones where it got 59.2% versus its rival’s 35.5%.

BJP managed to enhance its vote share over the 2012 levels in urban, rurban and rural seats, though in each case they were below the 2014 levels. However, with Congress also improving its share, the saffron party ceded a little ground compared to five years ago even in the urban and rurban seats, where it had won 35 out of 39 and 30 out of 45 respectively last time.

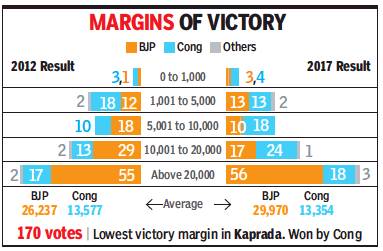

But what explains BJP winning far fewer rural seats despite a clearly higher vote share? Unfortunately for the party, a lot of the votes were used up in chalking up huge victories. Thus in the 39 rural seats it won, BJP had an average margin of nearly 18,000. In contrast, Congress had an average margin of just under 13,000 in the 52 seats it won. As many as 11 of the 52 seats were won by margins of under 5,000.

The same pattern held for the rurban seats too, with BJP averaging margins of over 26,000 in its 26 wins while the Congress average just about 14,000 in its wins. As a result, the six percentage point gap between the two parties did not quite deliver as much to the BJP as it typically would have in a bipolar situation.

In the urban areas, too, the average margin of BJP wins was way higher than that of Congress, but here the difference in vote share of almost 24 percentage points was just too much to allow Congress to benefit from a more even spread of its votes.

Cities remained loyal to BJP

From: December 19, 2017: The Times of India

See graphic:

Seats won by BJP and Congress in Ahmedabad, Rajkot, Surat and Vadodara, 2012 and 2017

Cong retained an edge in dairy belt

From: December 19, 2017: The Times of India

See graphic':

Seats won by BJP and Congress in the dairy belt, Gujarat-Assembly elections, 2012, 2017

5 key takeaways

December 19, 2017: The Times of India

1. GST and demonetisation

Could cease to be poll issues with the BJP prevailing in urban areas and largely retaining non-Patel vote.

2. Hindu turn

Congress put anti-Modi issues like the 2002 riots in deep freeze and Rahul's temple visits gave its campaign a 'soft Hindu' flavour. The BJP's current dominance could make this a lasting trend.

3. Caste quotas

The Patel agitation took a heavy toll on BJP but could not unseat it. The limits of quotas were exposed as the reservation demand made other communities wary.

4. Farm distress

Anger of cotton and peanut farmers over crop prices hurt BJP. Modi government may need to consider more pro-farmer policies, and pressure for loan waivers will rise.

5. Youth and jobs

Young voters have signalled impatience over stagnant employment. Slow-to-moderate growth could hurt BJP unless a trunaround happens well before 2019 Lok Sabha polls.

Why BJP Got More Votes, But Fewer Seats

Why BJP Got More Votes, But Fewer Seats, December 19, 2017: The Times of India

From: Why BJP Got More Votes, But Fewer Seats, December 19, 2017: The Times of India

Vote Share Rises To 49%, But Seat Tally Drops By 16

Slice and dice the Gujarat results along rural-urban axes, reserved and unreserved seats or by regions, and the seat tallies would convey the impression that there are sharp differences in the way different parts or sections of the state voted. Yet, look at the vote shares and a somewhat surprising pattern emerges. Across all of these divides, the BJP’s vote share is higher than that of the Congress.

This is true for every region, it is true for the rural/rurban/urban categories and whether it is SC or ST reserved seats or unreserved seats. Of course, the gap between the vote shares of the two parties would differ in each of these cases, but in every one of them Congress is behind BJP.

That is quite a surprise given the seat shares where, for instance, Congress has trounced the ruling party in the rural areas. Indeed, for the state as a whole BJP’s vote share of 49.1% in these polls is a slight improvement over the 47.9% it achieved in 2012 though a huge comedown if one were to compare it with the 59.1% share it got in the 2014 Lok Sabha polls.

Congress too improved its vote share from 38.9% five years ago to 41.4% this time.

But that still meant it was nearly 8 percentage points behind BJP, only a marginally smaller lead in votes than in 2012. In a bipolar election, a gap of that magnitude should normally result in a fairly big win for the leading party, as in fact happened last time.

Yet, this time round, the fight became agonizingly close for BJP, which finished just seven seats above the majority mark. What explains this inability of BJP to convert its lead in votes into a more sizeable lead in seats?

One clear reason was that much of this vote share came from building up huge wins in the cities. In the 33 urban seats it won, its average winning margin was about 47,400.

Similarly, it won its rurban seats by margins of over 26,000 votes on average. Impressive as those wins were, it was an example of a surplus of votes not really adding to seats.

The Congress votes were much more evenly spread. As a result it was able to win more seats than BJP even in regions where its vote share was actually lower. The most dramatic illustration of this was Saurashtra, where BJP won just 23 seats compared to 30 for Congress though its vote share of 45.9% was higher than the 45.5% won by Congress.

North Gujarat was not too different either. While BJP had a 45.1% vote share compared to Congress’s 44.9%, it won fewer seats — 14 to 17.

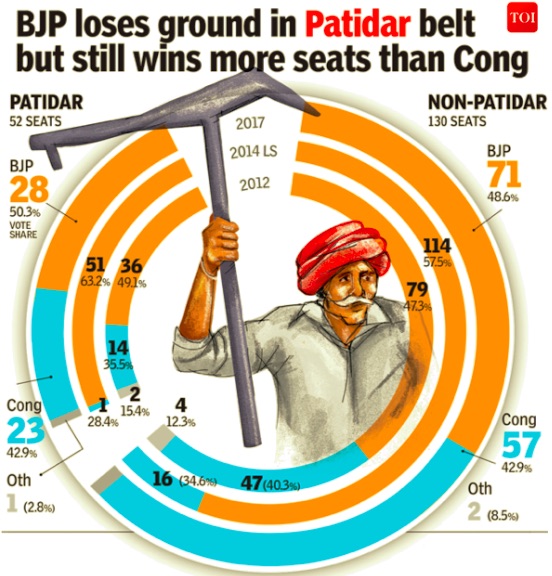

Incidentally, this was the only region where Congress had bettered BJP’s vote share in 2012 but the seat tallies were almost identical to the current ones. Considering how much had been made of the Patidar anger against BJP in these elections, it is ironical that the 52 seats in which Patidars form a significant chunk of the electorate were the ones in which BJP won a majority of votes (50.3%) and of seats (28).

However, this was also reflecting a regional variation in the way the Patidar dominated seats behaved. Of the 28 Patidar seats BJP won, only nine were from the Kutch-Saurashtra region. In contrast, 17 of the 23 seats won by the Congress where the community is dominant came from Kutch-Saurashtra.

These minor variations notwithstanding, what would give BJP reason to cheer in what became a closer election than it would have liked is the fact that it finished ahead on votes in every slice of Gujarat.

The communities

How Hardik, Rural Belt Took Cong To 80, December 19, 2017: The Times of India

Saurashtra Patidars ditch BJP, but Patels in cities remain loyal to Modi

Patidars have left a strong imprint on the Gujarat assembly elections and even though they may not have prevented BJP from winning for the sixth consecutive time, many would be happy that the ruling party’s tally has been reduced to double digits.

Out of 52 seats where Patidar component is 20% and more, BJP won 28 and Congress 23. An independent candidate won the Lunawada seat. The figure in 2012 was 36 for BJP, 14 for Congress and two for Gujarat Parivartan Party (GPP). Quite clearly, this is a distinct improvement for Congress.

The strong performance by Congress in Saurashtra (Congress 30, BJP 23, NCP 1) is also being attributed to Patidar support though agrarian issues may have played a bigger role. Analysts are also pointing at reverse consolidation of other castes which helped BJP in the other three regions. At the village level, other castes are at odds with the Patidars who are envied for their political clout, wealth, large land holdings, enterprise and remittances from abroad.

At the root of the success of the Congress formula of KHAM (Kshatriya-Harijan-Adivasi-Muslim) in 1985 was this caste conflict. The formula alienated the Patidars and many of them developed a deep dislike for the party. This disconnect was finally bridged in 2017 with Hardik Patel’s Patidar Anamat Andolan Samiti (PAAS) extending full support to Congress.

The aggression of Patidars may have alienated other communities resulting in a lower number of Patidar MLAs — from 47 in 2012 to 44 in 2017. These include 25 Leuva Patidars and 19 Kadva Patidars.

Two PAAS conveners — Lalit Vasoya from Saurashtra and Kirit Patel from Patan — won from Dhoraji and Patan seats, respectively. However, other PAAS-backed candidates, including Dhiru Gajera from Varachha, Ashok Jirawala from Kamrej, and B M Mangukia from Thakkarbapanagar, were defeated. Besides, BJP wins in Patidar strongholds of Surat and Mehsana indicate that Hardik may have had a limited impact on the elections.

Hardik, the biggest crowd puller after Modi, cut an isolated picture as he addressed media with a handful of his supporters as he blamed EVM tampering for BJP’s win. “I have been warning for three days now that a software company aligned with BJP has been tampering EVMs. There were many seats in Surat, Rajkot and Ahmedabad where BJP has won with a margin of 500 to 1,000 votes. This was made possible due to EVM tampering,” said Hardik.

C K Patel, president of Patidar Organisation Committee (POC), a consortium of six Patel organisations, claimed that the quota agitation did not make any impact in Surat or Saurashtra. “BJP has been wiped out in Saurashtra due to local issues like problems faced by farmers and small industries but Surat did not have any big issues against the government.”

Girish Patel, senior lawyer and activist, said that the Patidar anger was not converted into votes in Surat unlike some regions in Saurashtra. “Patidars in Surat, including those who have migrated from Saurashtra, are more affluent. The Patels from Saurashtra who migrated to Surat, are cut off from their roots… they are insensitive towards the issue of farmers and unemployed youths.”