Jails/ Prisons: India

Contents |

Administration

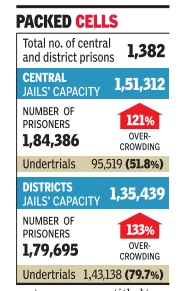

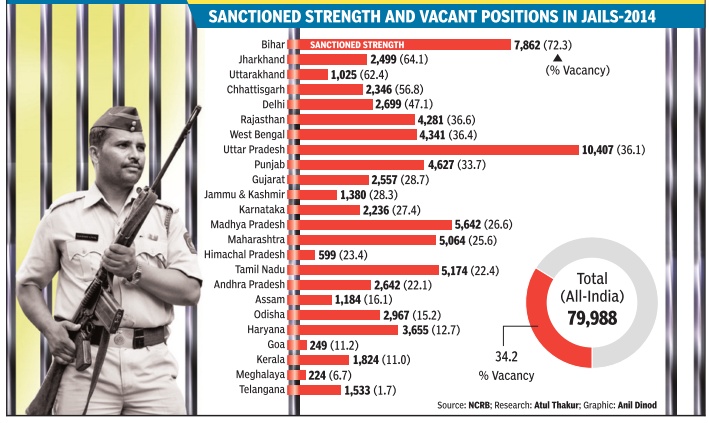

See graphics including ‘Total number of central and district prisons’ and ‘Sanctioned strength and vacant positions in jails.’

Crime inside jails

Bihar

India Today, February 3, 2016

Amitabh Srivastava

Bihar's jails are the new nerve centres of crime, offering a safe haven for gangsters to operate from.

In June 2015, the authorities at Sheohar divisional jail allowed a strange, joint "register entry", a process allowing undertrials to visit the jailer's office to deposit money. The people involved were an under-trial couple-kidnapping accused Puja and her gangster husband Mukesh Pathak-and, according to prison records, they parked some Rs 15,000 rupees with the office. But that wasn't all they were doing there. With the authorities looking the other way, the two apparently used the assistant jailer's office to pursue "physical relations". Only a select few, the top bosses of Sheohar jail, knew of the arrangement. But the fact was outed when, during a regular medical check-up in September, the doctor declared Puja pregnant. While the Sheohar jail officials tried to hush it up, it couldn't go on forever. Once the name of Mukesh Pathak-now roaming free after his daring escape last year-surfaced as the main accused in the December 26 killing of two engineers at Darbhanga, the police started digging deeper. Soon, the details of his in flagrante proclivities in jail tumbled out.

The facilitators

The prisons in Bihar have always had an unsavoury reputation, but of late things have taken a turn for the worse. Many known criminals now rush to surrender in the courts after committing a crime, which suggests they find the going better in jail than on the run. And what's not to like? Jails are safe havens, and since they have surrendered, it prevents confiscation of property and makes it easier to post bail. In September 2014, a joint report of the DM and the SP in Sitamarhi revealed how a select group of prisoners was allowed to avail facilities like ACs, coolers and mobiles. Even marijuana and liquor were provided to the "privileged" ones, it said. All this when the number of CCTV cameras have gone up, jails are less crowded, and the media is more active than ever. None of this has acted as an deterrent. And while the report did raise eyebrows, it has been conveniently buried. Take the Mukesh Pathak case, for instance. Pathak married Pooja in Sheohar jail in October 2013, after obtaining prior court permission. Jailer R.N. Shafi had then played the role of the girl's father and even performed the kanyadaan. Last year, after the jailer's office incident, the groom complained of medical issues and was promptly shifted to the government hospital in Sheohar from where he escaped on July 20 after drugging his guards. The irony here is the resultant inquiry did not even question the doctor who recommended him to hospital nor those who 'treated' him there for a week. (You can't blame the doctors either. In 2011, jail Dr Buddhadeo Singh was beaten to death in Gopalganj district jail after he refused to issue a fake medical certificate. According to latest NCRB figures, Bihar jail inmates made 7,051 visits to hospitals for "medical reasons" in 2014.) It's been four months since Puja's pregnancy was detected in September 2013, and an 'internal probe' is yet to conclusively establish anyone's guilt. IG prisons Prem Singh Meena says the probe has revealed "three dates when the couple could have had a private meeting (leading to her pregnancy). One such day was when they visited assistant jailer's office. The assistant jailer, head warden and warden of Sheohar jail have been served a show cause notice. We will take action once we get their response". Jha's gang is not an isolated example. Bihar's jails are the new hunting ground for criminals on the make. One of the reasons is also the low conviction rate. When it comes to percentage share of prison inmates, Bihar today has the lowest share of convicts (14.2%) against undertrials (85.6%)- the national average ratio is 31.4% convicts to 67.6% undertrials. This is also indicative of another fact. The number of arrests has gone up, and so has the number of police cases. But one of the worst conviction rates in the country means it is no deterrent to major crime. (In fact, criminals prefer the jail route nowadays than taking the police head-on. In 2001, the number of police 'encounter' deaths in shootouts stood at 41. The number dropped to two in 2015.) All this breeds a vicious circle. Once the police arrest a hardened criminal, he is produced in court that remands him to judicial custody. But, once the accused reaches jail, he starts operating with impunity from there. It leads to a horrific conclusion: higher the arrests, higher the crime. So it holds true that the jails-headed by a pliant gang of prison officials-have defeated the very purpose for which they were created. Bihar's jailed bahubalis are as active in this as your common variety don. In 2015 itself, independent MLC Ritlal Yadav, MLA Anant Singh, former RJD MP Shahabuddin have all had fresh FIRs filed against them for "jail violations". Leader of the Opposition, the BJP's Prem Kumar, says, "A majority of criminal cases committed in Bihar are linked to jails. Prison officials are either being pressured or are hand-in-glove with inmates. CM Nitish Kumar mans the home portfolio, he has to set things right fast or admit the situation is outside his control."

Killings ordered from jail

The Darbhanga murders of the two engineers, Brajesh Kumar Singh and Mukesh Singh, happened after their Gurgaon-based construction company, currently building a 120-km stretch of the Begusarai-Darbhanga state highway, refused to pay extortion money. The project, nearly halfway through, is worth Rs 700 crore. Police sources say the construction company was asked to cough up 10 per cent of the project cost as extortion money. The killings, which immediately put a question mark on the fate of big ticket projects in Bihar, and the investigation trail, led the police to another jail. Santosh Jha, mastermind of a flourishing extortion racket in Bihar and Mukesh's boss, was cooling his heels in Gaya central jail. Jha was in touch with hitmen via mobile phone and issuing elaborate orders via Facebook messenger, one of which was to bump off the two engineers. The extortion cell

Santosh Jha, 40, an ex-Maoist-turned-criminal, has over a dozen cases of murder, extortion, kidnapping and one of even 'landmine explosion' against him. He's believed to have extracted several crores from some of the major construction firms in Bihar. One of the new breed of tech-savvy criminals, Jha operates under the facade of a 'People's Liberation Army', which targets road contractors in north Bihar and affluent businessmen of Nepal. He mostly enrols his castemen as gang members and is said to have collected levies from over 1,000 people in north Bihar and Nepal. At least, six engineers have been killed in Bihar in the past for not caving in to the demands of the gang. Though Jha, who was arrested from West Bengal in June 2014, was lodged in Gaya, it was his influence which helped Pathak lord it over the Sheohar jail authorities. Police investigations have revealed that besides being in touch with gang members through FB, Jha even paid a fixed salary to his seven sharpshooters using net banking. Seized documents so far pertain to 25 bank accounts belonging to Jha's shooters. A dozen ATM cards belonging to gang members have also been seized. This is not a problem relating just to the Jha gang. Despite repeated recommendations, the prisons department is yet to instal jammers in any of Bihar's 58 jails while all agree that inmates using mobile phones has emerged as the single biggest reason for the spurt in crime. This also explains why Chief Minister Nitish Kumar's zero tolerance against crime has failed to have the desired effect in Bihar. K.C. Tyagi, Rajya Sabha MP and JD(U) spokesperson says, "The government has taken note of the rising criminal incidents with links to jails in Bihar. Nobody, including jail officials, will be spared if found guilty of irregularities." All the talk, though, will have to backed up by action. Considering Bihar's history and the spurt in violent crime in the last six months, that'll be no easy task.

Maharashtra

Use of cellphones in jails

The Hindu, December 4, 2016

Gautam S Mengle

For the affluent and well-connected jailbird, incarceration can come with all mod-cons, including liquor, drugs and even visits to dance bars. Most importantly, he is allowed to stay in touch with his underlings with his own mobile phone.

Police officials, both serving and retired, say the first thing convicts from organised crime syndicates do behind bars is set up a system that allows them to get whatever they want.

The well-oiled supply chain includes family, fellow gang members, lawyers, and prison staff willing to help — for a price. With the prisons department being understaffed and underpaid, that last crucial link isn’t hard to set up. Retired Crime Branch officials say this was at its peak in the 90s, when gangs like Dawood Kaskar’s ‘D-company’ and the Chhota Rajan gang were the most active.

The Arthur Road Central Jail in Mumbai, which housed most accused from the gangs, was divided into camps, mirroring gang memberships. Ambadas Pote, retired Deputy Commissioner of Police, calls it the nalli nihari racket, a dish of slow-cooked meat along with the bone marrow. Chuckling, he explains: “Family members of inmates with gang-land connections, with due permission of the court, would send tiffin boxes containing nalli nihari to the prison. Unknown to the staff, a SIM card wrapped in plastic would be stuffed inside the bone, which the inmates would remove and use. Cell phones, on the other hand, would be smuggled inside by bribing prison staff.”

When the racket was discovered by the Crime Branch around 10 years ago, it led to raids in several prisons and suspension of prison staff. Needless to say, inmates quickly found new ways to get the SIM cards.

“Court appearances are a boon for inmates when it comes to smuggling in SIM cards,” says a senior Mumbai Police officer.

“In crowded courts it is easy for anyone to slip a SIM to an inmate, and they’re easy to conceal and very easy to get rid of if there is a surprise check by prisons officials. And it’s equally easy to get a new one.”

Though the present day gangs are pale shadows of the groups that ruled the city — with dons and leaders either dead, serving life sentences, in exile or retired — SIM cards are still one of the items most frequently smuggled into prisons because they need to be changed frequently to make it harder for law enforcement to detect their use. Upgraded jail infrastructure, including CCTV cameras and surprise checks by vigilance teams, seems to have done little to stop the smuggling racket.

Active and undetected

Three recent incidents highlight the ineffective preventive measures.

• In 2013, gangster Abu Salem was allegedly shot at by Devendra Jagtap, the main accused in the murder of Mumbai-based advocate Shahid Azmi. This was when both were prisoners inside a jail. Jagtap fired two shots before being overpowered by prison guards, and Salem sustained an injury to his right hand. The fact that a gun and ammunition had been smuggled in to Jagtap shook the Prisons Department, leading to a search and departmental inquiry.

• In May 2013, Mumbai-based builder Rajaram Manjaokar was shot at in Borivali. The Mumbai Crime Branch arrested three men. The three confessed that they were operating on orders from Yusuf “Bachkana” Kadri, a Chhota Rajan lieutenant, who had organised the attack because Manjaokar had refused to pay extortion money. Bachkana was, at the time, a prisoner in Hindalga Central Jail, Belgaum. He was subsequently transferred to a central jail in Bangalore and several Hindalga officials were suspended.

• In 2015, three mobile phones were found in Taloja Central Jail, in the cell of Ravi Mallesh Bora alias D.K. Rao, another Chhota Rajan aide. His call data records revealed that he had made over 500 calls from those numbers in six months, a large chunk of them to international numbers. Rajan, who had been arrested a month earlier, had been on the run during this period and Rao is suspected to have kept in touch with him through these calls.

Additional Director General of Police (Prisons) Bhushan Upadhyay accepts that inmates getting access to cellular phones and running their gangs from inside jails is a reality despite efforts to prevent them. “We keep conduct regular surprise checks in central central jails to look for any such activities,” he said.

“Whenever such a case comes to light in our checks or through other channels, we take strict and immediate action against any prison staff who are found to be involved.”

CCTV surveillance

The Times of India, Jul 24, 2015

Put all prisons under CCTV camera surveillance: SC to govt

Amit Anand Choudhary

In a landmark verdict to ensure protection of human rights of prisoners, the Supreme Court on Friday directed the Centre and all state governments to put prisons under surveillance of CCTV cameras.

A bench headed by Justice TS Thakur also directed the states which have not set up Human Rights Commission to form the panel as soon as possible. There are many states and Union Territories like Himachal Pradesh, Meghalya, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Delhi, which have so far not set up the human rights watchdog panel. The court also asked the state governments to consider installing CCTV camera in police stations and lock ups to ensure that people are not subjected to unnecessary torture. It also directed that there must be two women constable in each police station.

Deaths Jailhouse

1994-2014: Deaths within the prison premises

The Hindu, September 27, 2016

Preventing death in custody

While the liberty of a person in custody can be curtailed according to ‘procedures established by law’, it cannot be stretched to extinguish life.

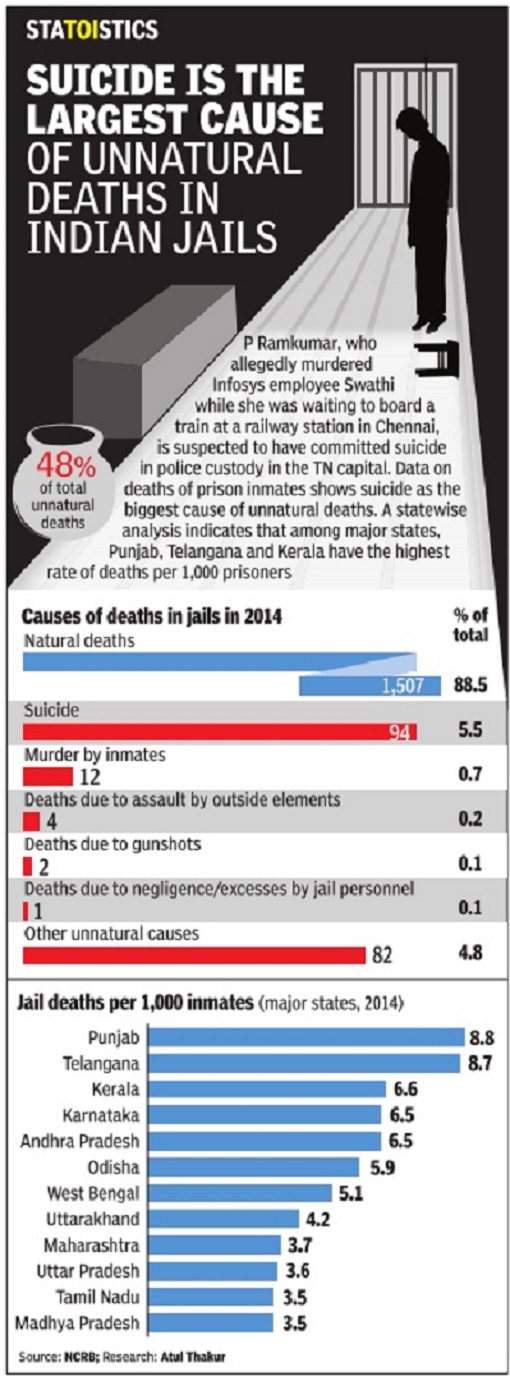

From 1995 to 2014, 999 suicides were reported inside Indian prisons. Tamil Nadu alone has seen 141 of them. The State houses less than 4 per cent of the country’s prisoners, yet it accounts for 14 per cent of suicides inside prisons. With such a poor track record, the State machinery should at least deliberate possible solutions.

Is Tamil Nadu the bad apple or is the entire orchard rotten? Data show that in the last 20 years, three inmates on average have been found dead daily in Indian prisons. In 2014, there were five deaths every day, so 35 deaths in a typical week. Two of these deaths were suicides. In the same period, the death rate inside prisons rose by 42 per cent. Ninety per cent of these deaths were recorded as ‘natural’, but what constitutes ‘natural’ in a custodial set-up is questionable.

Violation of rights

The numbers show that the prison department is ill-equipped to protect the health and safety of inmates. Little public scrutiny in jails provides the possibility of violation of basic rights. It is only when violations result in deaths that questions are raised, and even then only cursorily.

This perfunctory attention to prisons helps overlook the fact that deaths are the consequence of the everyday reality of prison life. Inmates live in despair of little or no contact with the outside world, are denied the basic desires to eat or wear clothes of their choice, to forge relationships. They wait for basic medical needs, their movements are restricted, and they are frustrated as they know nothing about their cases. As they are not taken to court often, they miss the chance of meeting a judge, their lawyers, and families. There is also lack of a mechanism to hear their complaints.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg. As an undercover operation in Uttar Pradesh’s Kasna Jail showed recently, abuse takes place in prisons. Extortions, corruption, and torture are common.

The only way to thwart what goes on in these institutions is to make them accountable. Prison monitors are mandated to regularly visit jails, listen to prisoners’ grievances, identify areas of concern, and seek resolution. These visitors include magistrates and judges, State human rights institutions, and non-official visitors drawn from society.

However, an upcoming Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative study (CHRI), ‘Looking into the haze — a study on prison monitoring in India’, shows that not even 1 per cent of Indian jails are monitored. In Tamil Nadu, according to recent media reports, most prisons await appointment of non-official visitors. As per National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) figures for 2014, just 500 inspections were made across the 136 jails in Tamil Nadu, perhaps by the official visitors. This means that there were less than four inspections per jail in an entire year.

Surveillance

The Supreme Court in 2015 ordered the Centre and the States to install CCTV cameras in all the prisons in the country. CCTV cameras serve two purposes: they bring on record incidents that could otherwise be suppressed, and play a preventive role in violation of rights, as the fear of facing consequences for the same would increase under vigilance.

Suicide is a critical problem in prison complexes — in the last 20 years, the suicide rate (suicides per lakh population) in prisons is recorded at 15.4. A person is 1.5 times more likely to kill himself or herself inside jail than outside it. In Tamil Nadu prisons, the suicide rate is higher than 40.

Providing counselling to inmates is crucial for them to deal with the ordeal they undergo in custody. But are prisons prepared for this? Tamil Nadu prisons have only sanctioned 105 correctional staff. Less than half the positions are filled. Out of the 13 psychologists sanctioned, only eight have been hired. With around 16,000 prisoners, this translates to one psychologist for every 2,000 inmates.

After Ramkumar’s death, the DG (Prisons) announced that a magisterial inquiry will be ordered. But does that mean anything? The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has expressed concern in the past about post-mortem reports “appearing to be doctored due to influence”. There is no information in the public domain about the details of these reports, whether the magistrate visited the death scene, what evidence was gathered, the time taken for the inquiry, the outcome, and whether prison officials were charged or found guilty.

Saving lives

The prison department is mandated to report all cases of custodial death to the NHRC within 24 hours of their occurrence. But the prison department data collated by the NCRB and the NHRC data don’t match. Also, almost half of the unnatural deaths in prisons are reported as ‘others’ by the NCRB. It is important that these ‘others’ be demystified.

While the liberty of a person inside custody can be curtailed according to “procedures established by law”, it cannot be stretched to extinguish life itself. The NHRC has repeatedly issued guidelines to prevent and respond to custodial deaths. It is time for the State governments to start taking these guidelines seriously. If the state works to promote communication between the inmate and his family and lawyer, increase conjugal visits, ensure adequate trained prison staff, and open up the prison to civil society, we might be able to save some lives. If not, we know who is responsible for the next suicide inside our jails.

Delhi, UP

Jailhouse deaths

By Anon, The Times of India, 12 March, 2013

The Times of India

“Unnatural” deaths: 2013

The Times of India, Jun 12 2015

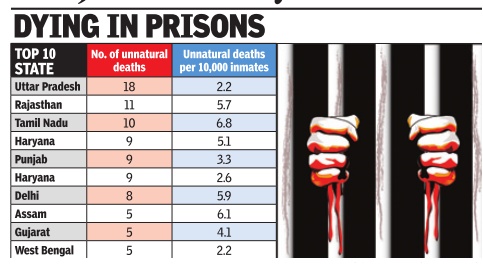

10 unnatural deaths occur in Indian jails every month

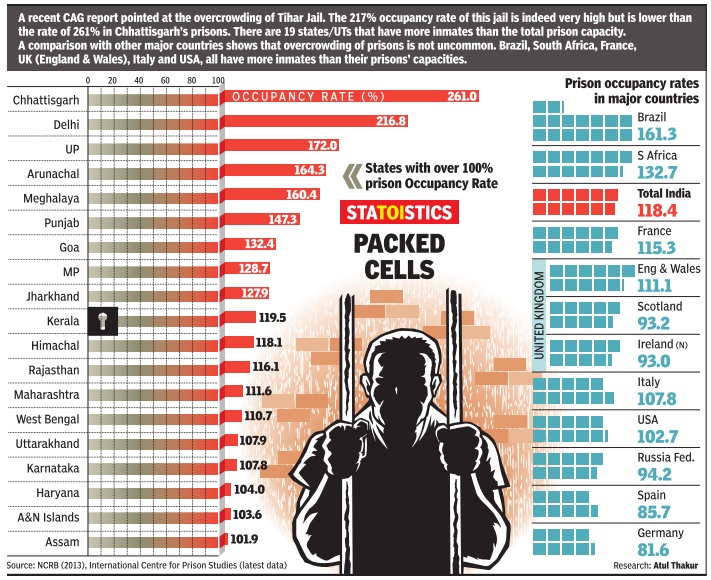

The murder of an inmate in Tihar is no isolated incident, with official data showing that there were 115 “unnatural deaths“ in India's jails in 2013, the latest year for which data is available from the National Crime Records Bureau. That's about 10 unnatural deaths every month. At 5.9 unnatural deaths per 10,000 inmates, Delhi's jails clock more than twice the national rate of 2.8 per 10,000 inmates. Whether this has anything to do with Delhi jails having over twice as many inmates as they are supposed to hold, against a national average of 118% occupancy, is a moot question.

The NCRB's prison statistics in India 2013 shows that of the 115 deaths due to unnatural causes, more than half (70) were officially classified as suicides, 12 were attributed to “assault by outside elements“ and eight to murders by inmates.With one execution and one death due to firing, the causes of deaths of 23 “others“ have not been spelt out.

The highest rates of unnatural deaths (per thousand inmates) were in Jammu & Kashmir, Tamil Nadu, Assam, Delhi and Rajasthan in that order. The lowest rates among bigger states were in undivided Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Maharashtra and Jharkhand. The prison statistics also show that barring Chhattisgarh, a state severely affected by Maoist insurgency , Delhi had by far the most overcrowded jails in the country . Chhattisgarh had 15,840 inmates in its jails which had a capaci ty of just 6,070, thus recording an `occupancy rate' of 261%. Delhi's 13,552 inmates were stuffed into jails meant to hold 6,250 people, an occupancy rate of 217%.The national average occupancy rate was about 118%, which shows that while jails as a rule are overcrowded in India, Delhi's prisons are almost twice as congested as the average.

UP, 2010-16: One prisoner dies every 26 hours

Deepak Lavania | TNN | Oct 17, 2016, In UP, a prisoner dies every 26 hours, The Times of India

AGRA: On an average, one prisoner dies in Uttar Pradesh every 26 hours. According to the state prison department's response to an RTI query, more than 2,050 prisoners have died in Uttar Pradesh since 2010.

Human rights activist Naresh Paras, who filled the RTI application, has witten to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), governor of UP and the PMO to take up the matter.

According to the response to the RTI query (a copy of which is with TOI), 2,062 prisoners died in a period of 74 months from January 2010 to February 2016. Out of them, more than 50% were undertrials. As many as 44 prisoners had committed suicide between 2010 and 2015. Around 24 died in police custody or allegedly got murdered.

"Age and natural causes behind the death of prisoners is just another excuse to escape the reality. The situation inside UP prisons is pathetic. There is a major lack of medical treatment for inmates and poor infrastructure at prison clinics. The state government and prison authorities have no concern for prisoners' rights. The atmosphere inside the prisons provokes convicts to commit suicide. Protection of priso ners is the prime responsibility of prison authorities, yet murders and unnatural deaths in jails and police custody continue to take place on a frequent basis," Paras told TOI on Sunday.

In 2010, 322 prisoners died. Out of these, half a dozen killed themselves, one died in police custody and six were murdered. In 2011, 285 prisoners died, including an undertrial from Pakistan.

There was an increase in the number of deaths in 2012, with 360 recorded, including another Pakistani undertrial. Three inmates killed themselves. In 2013, 358 prisoners died, while 345 lost their lives in 2014. This was follo wed by 345 deaths in 2015 and 53 in the first two months of 2016.

Inspector general of police (IG) GL Meena said, "Several initiatives have been taken in the past to provide better facilities to prisoners. Deaths reported due to old age and illness is quite normal and inevitable. The situation in prisons has improved in the past few years, but the number of prisoners has also increased. The state government is getting new prisons constructed. This will reduce overcrowding and help in developing better infrastructure. Efforts will be made to control the number of unnatural deaths of convicts."

Economics and jailhouse economy

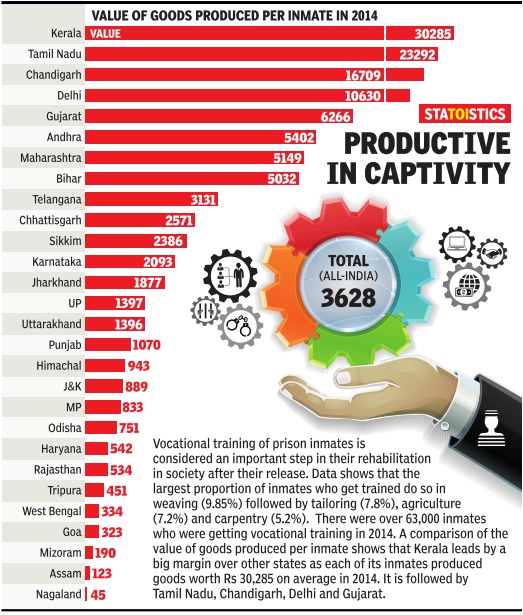

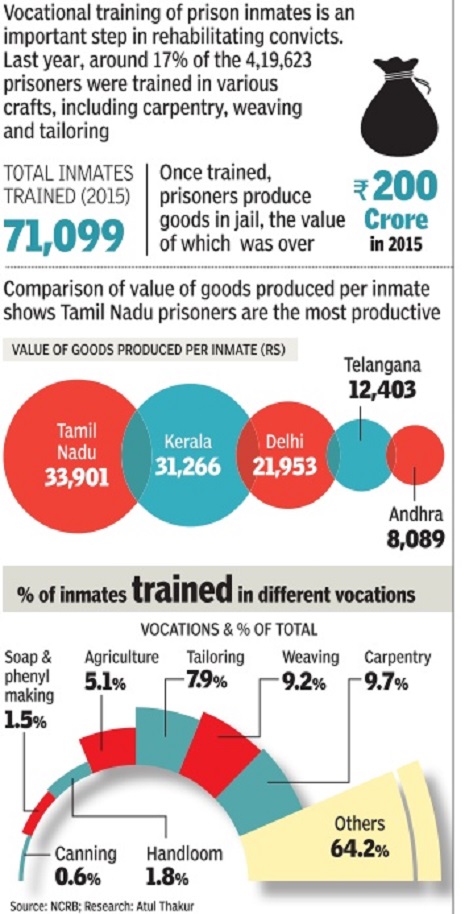

Vocational training of prison inmates is an important step in rehabilitating convicts.Last year, around 17% of the 4,19,623 prisoners were trained in various crafts, including carpentry, weaving and tailoring (PRISONERS IN TAMIL NADU ARE THE MOST PRODUCTIVE, HERE'S WHY, Nov 10 2016 : The Times of India)

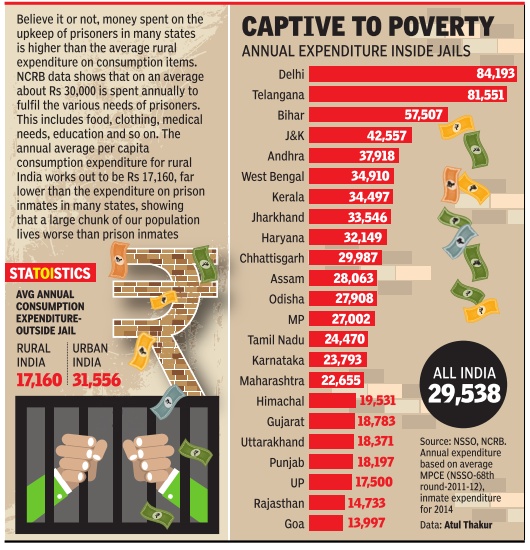

See graphics, including ‘Value of goods produced by prison inmates in India, statewise, in 2014,’ ‘Annual expenditure inside jails’ and ' Value of goods produced by jail inmates...'

The Times of India

Prisoners as labour workforce

Corporate users

The Times of India, Apr 24 2016

Joeanna Rebello

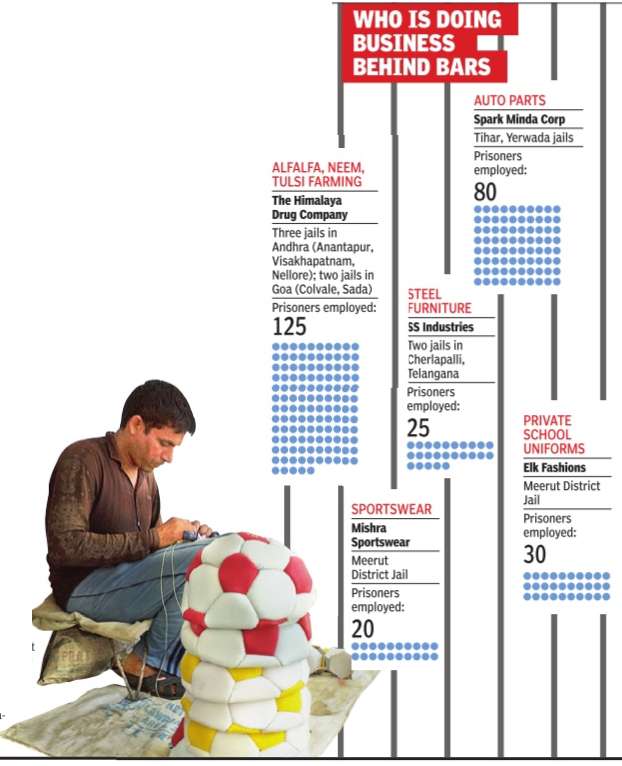

Private sector goes to prison

Jail inmates are fast emerging as the new labour workforce for India's private sector. Is it corporate opportunism, penal reform, or a bit of both? In the 21st century marketplace that makes much of the back story of a product, here's a twist: the football, floor tile, shampoo, or car you own could have featured a prisoner in the workforce. The Indian prison industry -manufacturing for the state or making prison-branded goods so far -has lately started working for the private sector. From The Himalaya Drug Company and automotive component manufacturer Spark Minda Corporation, to small manufacturers in Meerut in UP and Yamunanagar in Haryana, the private sector has started outsourcing -or in prison parlance, `in-sourcing' -jobs to jails.

Himalaya's supply chain for alfalfa, a medicinal plant that it uses in several health products, can be traced to a prison farming programme established five years ago in Karnataka Open Air Jail, Bengaluru. It was later extended to three prisons in Andhra Pradesh and two in Goa. “Forty-five percent of our Alfalfa requirement is sourced through contract farming, of which about 3% comes from the Prison Farming Programme,“ says Himalaya CEO Philipe Haydon. “Our goal is to source the entire alfalfa requirement from this programme.“

Three months ago, 20 prisoners in Colvale Central Jail, North Goa were trained by the pharma's field staff in farming and harvesting.They're paid the state's daily prison wage of Rs 120 for skilled labour (Rs 80 for semi-skilled work). Himalaya provides the seeds and manure, and buys back the harvest, which varies from 6.5 to 8 metric tons per prison annually, at an undisclosed price.“Now that we're earning some revenue, we plan to expand such partnerships and scale up wages,“ says Elvis Gomes, Goa's IG, prisons. And so 10,000 square metres in Colvale and Sada Sub Jail have been set aside for the project.

Late last year, 30 inmates at Pune's Yerwada Central Jail were recruited by Spark Minda, which started an assembly unit for automotive wiring harnesses there, after its successful operation in Tihar the year before. “We borrowed the idea from our counterparts in Germany who employed prisoners,“ says N K Taneja, Group Chief Marketing Officer. The company currently employs 80 inmates across both correctional facilities, but believes there's room for at least 200. “Before we got into this partnership, we ran it by our clients, Maruti Suzuki and Mahindra & Mahindra who approved of the initiative,“ he says.

For optimal results from their two-month training, Spark Minda only hires convicts in for the long haul -five years and more. While all prisoners get a certificate of work, Yerwada's inmates earn Rs 200 a day, part of which goes to the prisoners' welfare fund and the institution itself, and Tihar's get the standard wage of Rs 110. Tihar also earns a separate monthly rent of Rs 12sq ft from Spark Minda for use of their premises.

Meanwhile, in Yamunanagar District Jail, 200km from Gurgaon, two dozen inmates produce ceramic floor tiles for a local firm. “They work six to eight hours a day for Rs 40,“ says IG Jagjeet Singh, adding that Ambala Central Jail produces steel furniture for another company .

Indian prison officials speak glowingly of the PPP model -also interpreted as the Private Prison Partnership -saying its income offsets costs. (In 2014-15, the 88,221 inmates lodged in UP prisons cost the state Rs 74 lakh.) But the model also assists in rehabilitation by skilling prisoners for life beyond bars.And finally , as per prison wisdom, a `busy convict is an easy convict'.

Prison brass say convicts are never pressed into work, although they may be nudged. “We first select people who know the work, then bring in those interested but unskilled,“ explains DIG prisons, Telangana, V K Singh. The assembly of electric metre boxes for Hyderabadbased Linkwell Telesystems, and steel furniture for SS Industries are in-sourced to the central and open prisons in Cherlapalli.

“We vet companies for security risks, potential environmental pollution, risk to prisoners' health, their business plans, and other factors. We have valuable land and we don't want firms that only wish to take advantage of our real estate,“ Singh maintains. Not to mention captive labour. The prison-industrial complex worldwide has been under greater scrutiny in recent years.Contracting companies in China and America have been condemned for their exploitative prisoner wages (as low as 2 cents an hour) -and for profiting off the taxpayer, as prisons are usually state funded.Moreover, companies don't have to worry about absenteeism or health benefits and pension.

Nikhil Roy , programme development officer at the London-based Penal Reform International, believes there's nothing wrong with the profit motive. “It's the exploitation of prisoners that we need to guard against. Hence, the Mandela Rules (the UN's recently revised standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners) do not rule out profit but make it clear this should not be “subordinate“ to the welfare of the prisoners,“ Roy says on email.

The conservative view has long argued that prisoners don't deserve market minimum wages because the state sponsors their bed and board anyway . Also, their crime or alleged crime denies them equal wage rights. So income, however paltry , ought to be regarded as a bo nus. But the reformist view is that even prisoners have families to supt port outside, and a decent income earned in incarceration will not only help their kin, but also give them a sense of purpose and dignity .

(In some cases in Tihar, 25% of the convict's income is remitted to the family of his victim).

But even though companies are less wary of their association with prisons today, calling it their CSR, jail authorities know they still have to tread lightly. “If we strike too , hard a bargain on remuneration, companies will stay away,“ points out V K Singh. Kiran Bedi, former IG prisons, Tihar is credited with planting the PPP model in Delhi prisons in the '90s. “Today prison reform is a movement and big companies want their association with it to be visible; earlier they kept a low profile because it could have been be construed as forced work,“ she says.

Signs of changing times are evident from the number of jails being roped in. While Spark Minda plans to set up a unit in Nagpur as well, Himalaya is scoping out Kerala, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal.

Bedi, for one, is upbeat. “I am glad companies are coming in and skilling prisoners at a low cost. Entering a prison is not risk-free, and yet they come here instead of employing elsewhere. I look at it as the glass half full.“

Furlough (discretionary leave) for convicts

The Times of India, Sep 02 2015

Swati Deshpande

30-day parole to Dutt raises questions

Experts wonder whether jail authorities applied their mind in deciding his plea

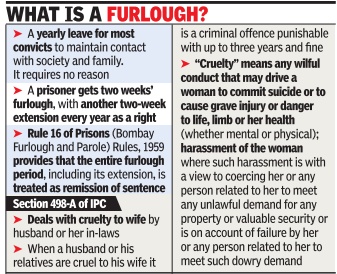

Furlough is discretionary leave that convicts are allowed to enable re-integration with society upon their final release. It requires no specific reason. But parole is leave granted for a specific reason. It is not counted towards days served in prison, unlike furlough.

The jail manual requires a plea for parole to be processed within 45 days after it is made.The convict files and sends a parole plea to the jail superintendent, who forwards it to the divisional commissioner.The decision includes seeking a police report and communicating approval or rejection to the convict.

Delay in decision-making raises pertinent questions about whether prison authorities apply their mind, said a lawyer. Many lawyers say while the delay has come to light in Dutt's case, many applications remain pending for months, unnoticed and forgotten. “The rule book must be followed strictly as the high court has ruled in several cases,“ said advocate Farhana Shah, who has represented many convicts whose parole pleas were not decided for months. She said while Dutt's leave was “rightly granted“, though delayed, the “same consideration“ should be made for other inmates whose pleas are later rejected on the grounds that the reasons are no longer relevant. “If a parole plea is decided, for instance, after the marriage of the child of a convicted prisoner (for which leave was sought), it would defeat the very purpose,“ she said.

“If a plea is not decided in time, an extension plea would be rendered meaningless,“ said another lawyer, adding that even for furlough, the authorities are expected to verify the convict's conduct and record and only then grant leave.

Overcrowding

Jails in UP, MP, Chhattisgarh most crowded

Deeptiman.Tiwary @timesgroup.com New Delhi

The Times of India Aug 19 2014

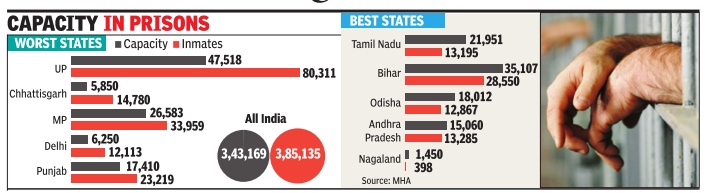

Overcrowding of prisons is often cited as the reason for inmates living in pitiable conditions. However, official data show prisons in almost 20 states have less number of inmates than their official capacity or are just at par.Actually a few states, including UP , MP, Chhattisgarh and Delhi, have skewed the national average with massive overcrowding their prisons.

UP alone contributes to overcrowding by close to 32,000 prisoners when cumulative overcrowding across the country stands at close to 42,000. In its 65 jails with a capacity of 47,518 inmates, UP has crammed 80,311. Chhattisgarh is another laggard state with its prisons overcrowded by 8,930 inmates against a capacity of 5,850. Delhi, whose Tihar jail has often been in the news for overcrowding, has almost twice the number of inmates against its capacity . Madhya Pradesh jails, from where six SIMI accused broke free last year, are overcrowded by over 7,000 inmates.

Curiously , Bihar is one of the best performing states along with Tamil Nadu in building optimum capacity in jails. While TN has almost 9,000 less occupancy against a capacity of 21,951, Bihar over 6,500 less inmates against its total capacity . Odisha is another state where prison capacity has improved over the years with almost 30% less occupancy against capacity

Much of these positive changes have come about in the past one decade when the Centre launched seven-year scheme worth Rs 1,800 crore for modernization of prisons. i In 2002, there were 1,135 jails t across the country with a capacity to hold 2,29,874 inmates.However, 3,22,357 inmates were t crammed in these jails. Between 2002 and 2012, number of jails increased to 1,394 with the capacity improving to 3,43,169.By the end of 2012, there were 3,85,135 inmates in these jails.

While number of inmates increased by close to 50,000 in this period, the capacity of prisons improved by over 1 lakh easing pressure on infrastructure and making life better inside jails.

India and the world: Prison population

Jun 15 2015

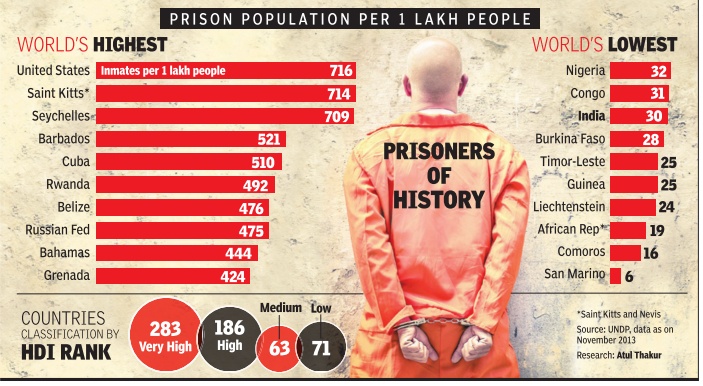

With 716 prisoners per lakh of people, the US has the world's highest incarceration rate. Among 190 countries for which data is available, India is ranked 183rd in terms of the incarceration rate. This rate is dependent not just on the crime rate, but also on urbanization, efficiency of the criminal justice system and marginalization of some sections.Thus, there is a huge difference in incarceration rates among coloured and white people in the US. In India, Muslims, Dalits and tribals constitute 53% of the prison population -much higher than their share in the population.

Judicial intervention to curb overcrowding

The Hindu, October 14, 2016

Krishnadas Rajgopal

SC says jails are overcrowded by 150 %, laments plight of inmates

“Fundamental rights and human rights of people, however they may be placed, cannot be ignored only because of their adverse circumstances”

Blaming Delhi for paying “little or no attention” to the fundamental rights of under trials and convicts, the Supreme Court said it is “not only tragic but also pathetic” to find that prisons in the national capital, along with half a dozen States across the country, are overcrowded by over 150 per cent.

A Bench led by Justice Madan B. Lokur, in a judgment on a suo motu Public Interest Litigation (PIL), observed that prisons are crammed with inmates by over one and a half times the permissible limit.

“Fundamental rights and human rights of people, however they may be placed, cannot be ignored only because of their adverse circumstances,” the judgment observed.

Action not taken The recent judgment refers to jails in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan in this context, while observing that it was “unfortunate that in spite of directions by the Court, the prison authorities have not been able to take any effective steps for reducing overcrowding in jails”.

The court found that authorities have defied repeated orders of the Supreme Court — the latest ones being on February 7 and May 5 of this year — to draw a “viable” plan of action to de-congest jails. Instead, prison authorities have banked on ad hoc proposals like the construction of additional barracks or jails, and these proposals have no time limits for implementation.

Besides, the Court also found that the Ministry of Women and Child Development is yet to frame a Manual for Juveniles in Custody under the recently amended Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015.

Distressing

The Supreme Court directed the Ministry to get the manual ready by November 30 and present it in court. It also ordered the Ministry of Home Affairs to receive and collate plans of action for de-congesting jails from the various States and Union Territories in the next six months. Moreover, the SC directed the government to prepare a viable Plan of Action within the next six months and hand it over to the apex court by March 31, 2017.

“We are a little distressed to note that even though this Court has held on several occasions that prisoners, both undertrials and convicts, have certain fundamental rights and human rights, little or no attention is being paid in this regard by the States and some Union Territories, including the National Capital Territory of Delhi,” the judgment observed.

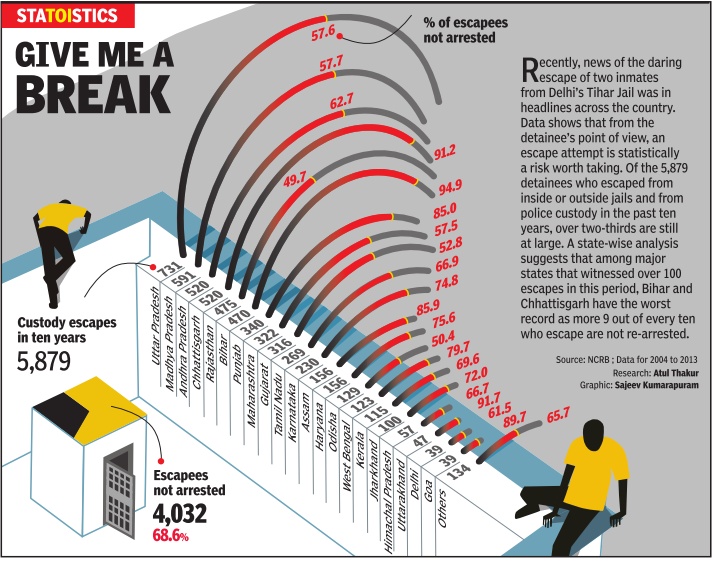

Those who escape are rarely re-arrested

WHY IT MAKES SENSE TO RISK ESCAPING FROM JAILS, Nov 08 2016 : The Times of India

The controversy over the escape and gunning down of eight undertrials of Bhopal Central Jail in Madhya Pradesh hides the fact that from the detainee's point of view, an escape attempt is a risk worth taking because statistics show that two-thirds of those who flee from prisons are never caught again. In Punjab, for instance, 32 fled from jails in 2015, none was ever caught again.

Undertrials

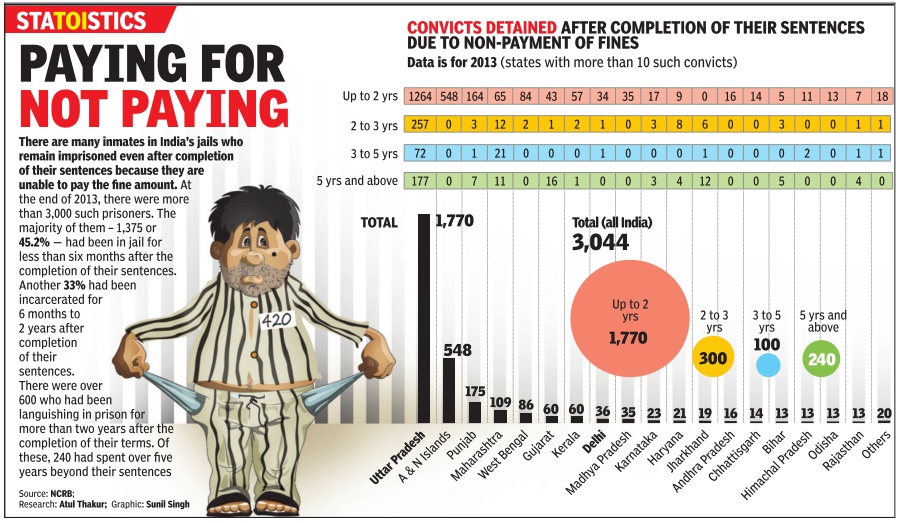

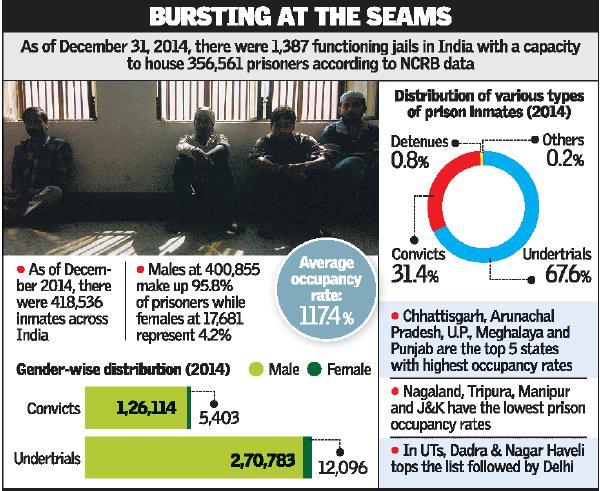

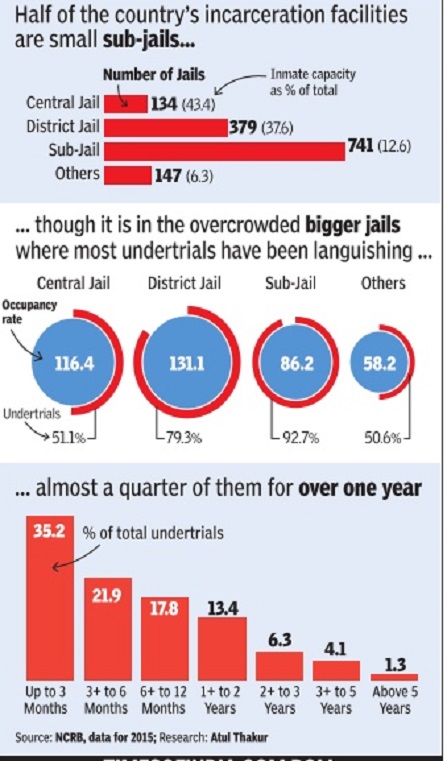

67% OF PRISONERS ARE AWAITING TRIAL, NOT SERVING A SENTENCE, Nov 04 2016 : The Times of India

ii) Jails more likely to have undertrials;

iii) How long undertrials are likely to be in prison, awaiting trial.

The Times of India

Despite various government initiatives such as releasing of certain undertrials who have completed more than half of the imprisonment that they would get if sentenced, criminals awaiting completion of trial constitute the bulk of the country's jail population. They are crammed in jail that are operating over capacity