Lavasa

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Sharad Pawar and the project

Kiran D.Tare , Still born city? “India Today” 26/6/2017

The Maharashtra government's announcement on May 23, revoking the special planning authority (SPA) status for Lavasa, could have been passed off as just another policy diktat, but for the protagonists involved.

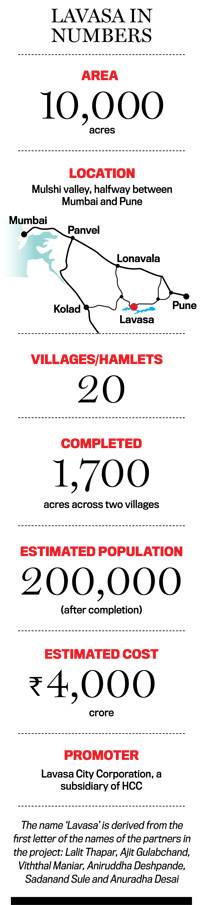

Lavasa, an under-construction hill city near Pune, was originally visualised by Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) strongman Sharad Pawar. His son-in-law, Sadanand Sule, even owned a 12.7 per cent stake in the project until 2007. The history of the project, though, goes back to the early 2000s. As the story goes, while being flown from Mumbai to Pune in a helicopter, Pawar spotted a large tract of vacant land in the Mulshi valley area of the Sahyadri mountain range in Maharashtra. Thinking of it as an ideal spot to plant a new, model city (as conceived by his friend, Aniruddha Deshpande), Pawar took the proposal to realty baron Ajit Gulabchand and his company, HCC. Gulabchand is an old friend of Pawar's, and Lavasa City Corporation (LCC), the firm responsible for the city's construction, is part of HCC's real estate wing.

After the May 23 announcement, political observers were quick to suggest that the fate of Lavasa is yet another stick that chief minister Devendra Fadnavis could wield against the NCP and Pawar, whose nephew, Ajit, is currently facing an Enforcement Directorate probe in connection with alleged benami companies bagging irrigation contracts. The significance of the move was not lost on Pawar, who called on Fadnavis that very evening "to discuss issues pertaining to farmers". While what they discussed remains a secret, Pawar's continuing interest in Lavasa is well known. Lavasa was the first private project to receive the SPA tag, granting it the power to draw up land use plans, develop land in its jurisdiction and sanction construction. The late Vilasrao Deshmukh, then chief minister, had granted the project SPA status at a special cabinet meeting held at a Lavasa hotel in June 2007.

In 2010, construction came to a halt because of restrictions imposed by the Union ministry for environment, Lavasa had become a pawn in a power struggle between the Congress and Pawar. That year, then Union minister Jairam Ramesh had dispatched an official to Pune to serve LCC a stop-work notice, citing destruction of the environment. It was a big blow to Pawar, then Union agriculture minister. Though the company soon overcame the shock, undertaking a plantation drive and taking measures to stop soil erosion, the allegation that it was destroying the local environment stuck.

As a result, HCC had to postpone its initial public offering (IPO) for Lavasa. The company has tried to launch the IPO thrice since then, but the market let them down. HCC holds a 68 per cent stake in LCC, with the remaining held by the Avantha Group (17 per cent), Venkateshwara Hatcheries (8.8 per cent) and the Maniar family (6.2 per cent). So far, several apartments and bungalows have been constructed, as well as hotels and conference halls. A one BHK apartment in Lavasa today costs about Rs 30 lakh, while the bungalows go for about Rs 4 crore. Among the prominent buyers is former Union minister Arun Shourie. "There was no issue when I bought the property there," Shourie says. "I have no comments to offer on what will happen (to Lavasa after the latest decision)."

Fadnavis's decision to cancel Lavasa's SPA status was based on a report by the state public accounts committee (PAC) last year. The panel, headed by Congress MLA Gopaldas Agrawal, had noted that between October 2002 and February 2009, Lavasa purchased 214 hectares of land without taking the necessary permissions. The land was regulated under the Urban Land Ceiling Act, which mandates that the permission of the concerned district collector must be taken before purchasing it. The collector's office has recovered penalties of Rs 11.9 crore from Lavasa for flouting the norms. A 2012 report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India had also recommended the cancellation of Lavasa's SPA status. "The PAC recommended revoking Lavasa's SPA status," says Fadnavis. "Now, the Pune Metropolitan Region Development Authority (PMRDA) will be the planning authority for it."

The project has met with criticism from environmental activists as well. Vishwambhar Choudhary, who had filed a petition in the Bombay High Court, alleges that Lavasa violated floor space index (FSI) norms while constructing residential and commercial buildings. "Lavasa already has [constructed] buildings in two of the 20 villages. I hope the remaining 18 will be saved now," Choudhary says.

State BJP spokesperson Madhav Bhandari, Choudhary's co-petitioner, also alleges that Lavasa's construction of a barrage at Varasgaon dam, which supplies water to Pune, went against the provisions of the Irrigation Act. "Water was made available to Lavasa because influential politicians are associated with it," Bhandari alleges. An LCC official denies allegations of FSI violation and water diversion. "All construction was as per rules. The Krishna Valley Corporation had allowed us to construct the barrage. Moreover, the government representative was at all the SPA meetings. Let them do a scrutiny of our decisions," he says.

Meanwhile, Fadnavis himself downplayed the May 23 announcement, saying "Lavasa will now have to approach the PMRDA for permissions. If there are violations, an inquiry will be conducted... but that does not mean there will be one for every decision." An official with Fadnavis's office, though, says the CM's statement was only for show. "The PMRDA will go through each and every paper pertaining to Lavasa," he says, pointing out that the authority reports to the CM's office.

Lavasa City Corporation, while denying the allegations of irregularities, tried to put a positive face to the May 23 announcement. "This brings Lavasa into the Pune metropolitan area, and the company will benefit from the broader urban development plan of the region," it said via a press release. An official with LCC, who does not wish to be identified, also dismisses allegations of FSI violations and water diversion. "We have [undertaken construction] as per the rules. The Krishna Valley Corporation allowed us to construct the barrage. Moreover, the government always sent its representative to the SPA meetings. They can conduct a scrutiny of our decisions now."

Gulabchand himself says he can't comment on the matter as he has not yet received a formal order from the government. "I was travelling abroad when the government announced its decision. I was expecting them to send us a formal order in a day or two, but even after a week we have not received any communication," he says. "We don't know what the exact order is yet." HCC itself is cagey on whether it sees a concerted effort by the government to create problems for it. A company official says that decision-making by the government slowed down a few years ago, and is still languishing. He refers to another decision by the government to delay a payment of Rs 640 crore, due to HCC for the construction of the Bandra-Worli sea link in Mumbai.

For her part, Supriya Sule, Sharad Pawar's daughter, has washed her hands of the project, saying that her husband Sadanand had "very very nominal" shares in Lavasa which he sold "ages ago". "I don't have a view on the Lavasa development," she says. "We sold [our] shares ages ago, before the project became large. We personally have zero financial association with it." She refuses to comment on Lavasa's future either. "It doesn't concern me. It is a decision taken by the government of Maharashtra. I haven't thought about whether Lavasa has a future or not."

Why the project failed

HIghlights

Lavasa has turned out to be a typical example of a large-scale infrastructure project gone bad, saddling its bankers with unpaid dues

Estimates suggest, reviving the sagging project would require as much as Rs 100 billion just to start with

This onetime hilltop paradise is becoming for some a hell on earth.

The days of zero crime are over. Garbage collection is sporadic, so litter soils the man-made lake. Storefronts are vacant. Signs of neglect are everywhere: maintenance is late or nonexistent. And that’s for the construction already done. For the unfinished building works—i.e. most of it—there is little happening.

Two decades ago, then-billionaire Ajit Gulabchand envisioned something very different: a city called Lavasa, modeled on the cotton-candy harbor of Italy’s Portofino, a four-hour drive from the slums and pollution that pervade so much of India’s financial capital of Mumbai. To deliver that dream, he hired the architects at HOK, creators of LaGuardia’s Airport Central Terminal B in New York and the Barclays world headquarters in London. Design awards and global news coverage followed.

It would be India’s first privately built and managed city, one of five planned for 30,000 to 50,000 people each, soaking up settlers from the hinterlands looking for opportunities in urban areas. No more government bureaucracy. The cost would be billions of dollars. (The company declined to provide a full estimate.)

Today Lavasa is an incomplete shell housing some 10,000 people, a symbol of the excesses gripping the world’s second most-populous nation. Lavasa Corporation Ltd. faces what may be its final reckoning, as India’s central bank forces lenders to restructure debts quickly or take defaulters to bankruptcy court.

Arguably even worse off than current residents are the thousands of people who have put down their life savings or borrowed money to buy property here, only to fear it may never get built.

“In 2012, when we first came to this place, it was booming—from being a vibrant place it has come down to be a ghost town,” said David Cooper, a 63-year-old resident of Lavasa’s home for senior citizens, Aashiana. “There is hardly anyone who wants to stay.”

Generally abandoned is the original plan of developing five towns with theme parks, school campuses, sports complexes and research centers in the scenic hills of the Western Ghats, a UNESCO world heritage site known for its evergreen tropical forests that shelter 325 species of vulnerable or endangered animals, birds and fauna. The first and only town to be built—Dasve—is littered with concrete skeletons.

Lavasa is a typical example of a large-scale infrastructure project gone bad, saddling its bankers with unpaid dues that are helping drive record losses at many Indian lenders. Lavasa defaulted on dues payable to bondholders and has delayed repayment to other creditors including banks, the company said in a May 3 filing. Its obligations are among the $210 billion stressed assets looming over India, which has one of the world’s worst bad-loan problems.

Lenders as early as August may be left with no choice but to take the firm to bankruptcy court if its backers and bankers can’t decide on a revival plan. The Reserve Bank of India in February scrapped various restructuring programs that had kept Lavasa on life support.

Lavasa was conceived by Gulabchand as India’s first private hill city in 2000, following similar private developments in the US like Seaside, Florida, or the Disney development of Celebration. Now the unit of his Hindustan Construction Ltd. is struggling to repay its Rs 41.5 billion of debt, leaving the township to slowly slip into disrepair. Neglect has taken the Mediterranean sheen off once-bright red and yellow buildings. The cobblestone streets and stone bridges are growing moss. Sidewalks are crumbling in places.

“We are managing the project with whatever limited resources we have,” Hindustan Construction chairman Gulabchand said in an interview at the company’s sprawling office complex in an eastern suburb of Mumbai. “We are now looking forward, to seek a resolution plan.”

Curious tourists and locals looking for a break from city life once flocked to the streets of Dasve, but now they now look deserted. Many restaurants and coffee shops on the promenade facing the lake have shut. The number of visitors has dropped in the past two years, said Mukesh Kumar, a general manager at the Waterfront Shaw, a 43-apartment hotel.

Prakash Sahoo, a retiree who has been living in an apartment near the Dasve lake for four years, bemoans the seven years of hotel construction that’s still a shell just outside his balcony. And yet, Sahoo calls Lavasa India’s paradise city given its beautiful architecture, well-planned infrastructure, reliable water and power supplies, clean air and less traffic.

Erstwhile Mumbaities, David Cooper and his wife, Zerin, are worried though about the rapidly thinning security staff and recent break-ins.

Madhav Thapar, another apartment owner, is disheartened while describing the lawlessness and deterioration gripping the hill city. What’s worse, Sahoo says: The Lavasa civic body is privately managed so residents have little access to its functioning or fund management.

Plans for this retreat from modern India—including a possible IPO of the developer—came off the rails in November 2010 when the environment ministry halted construction for about a year, alleging rule violations. Its cash flow quickly dried up. Efforts to tap equity markets fell through with investors nervous of further government intervention.

About a year later, construction resumed after approvals came through to build on 21 square kilometers—almost the size of Macau. But by that point the project was cursed.

Despite getting environmental clearance, the company had lost the cooperation from government officials, Gulabchand said. Lenders balked at complexities.

The 70-year-old scion of the construction company—known for building roads, power plants, tunnels and more than 300 bridges around the country—is now in discussions with as many as three strategic investors, including private equity players and banks, to come up with a solution and is open to either a partnership, or selling his stake in the project entirely.

“I am open to all possibilities. This is the only way forward,” Gulabchand said.

Undeterred in his vision, Gulabchand stressed that whoever invests in the project will have to develop the five towns as the project was originally planned under the hill development policy. “Obviously it has to be developed,” he said. “There is no escape, and the question is of the pace. It may take little longer.”

It may not be easy to find the right suitor for Lavasa considering the cost involved. Reviving the project would require as much as Rs 100 billion just to start with, Gulabchand estimates.

For a glimpse of where Lavasa may be heading, look to Aamby Valley, another affluent township outside Mumbai turned ghost town built by a separate developer. That $5.5 billion township is facing liquidation after its backer defaulted. After repeated failed attempts to auction Aamby Valley, the court ordered piecemeal sale of the project’s land. But a slump in India’s property market is making matters worse.

“Selling big land banks like Lavasa or finding investors who can write big checks for a project like that would be quite a struggle in the current environment,” said Amit Goenka, managing director of Nisus Finance Services Ltd. “There are just too many distressed sellers and not enough buyers in this market.”