Monsoons: India

(→2015) |

(→Years in which the monsoon arrived early) |

||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

= Years in which the monsoon arrived early = | = Years in which the monsoon arrived early = | ||

[[File: years in which the monsoon arrived early.jpg|Years in which the monsoon arrived early: 2011-2014; Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com//Gallery.aspx?id=15_05_2015_009_024_009&type=P&artUrl=Monsoon-may-be-early-but-El-Nino-fear-15052015009024&eid=31808 ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | [[File: years in which the monsoon arrived early.jpg|Years in which the monsoon arrived early: 2011-2014; Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com//Gallery.aspx?id=15_05_2015_009_024_009&type=P&artUrl=Monsoon-may-be-early-but-El-Nino-fear-15052015009024&eid=31808 ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

=Droughts in India= | =Droughts in India= | ||

[[File: Droughts in India.jpg|Some facts: Droughts in India, Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com//Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=DEFICIENT-RAIN-03062015023056 ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | [[File: Droughts in India.jpg|Some facts: Droughts in India, Graphic courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com//Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=DEFICIENT-RAIN-03062015023056 ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

Revision as of 16:47, 20 August 2015

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Monsoons: India

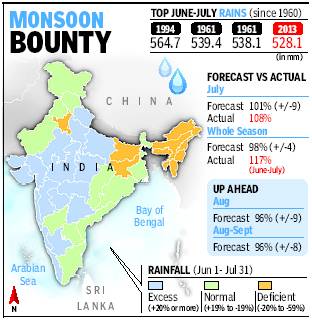

Monsoon going strong, hopes soar

Rains Set To Cross 100% Of Long-Period Average, Record Rice Output Likely

Neha Lalchandani TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/02

A bountiful monsoon normally benefit the kharif crop and augurs good rice production with the area under sowing touching 196 lakh hectares in 2013, a 16 lakh hectare increase over 2012.

Monsoons that crossed the 100% mark

Since 1901, there have been 59 years when the monsoon has crossed 100% of the LPA. Since 2000, there have been only four years when monsoon crossed the 100% mark. These are 2003, 2007, 2010 and 2011. The projection is welcome news for the government as a stuttering monsoon can cast a long shadow on its political fortunes with growth slipping below 5% and high food inflation — prices for consumers rose 11.84% in June — proving a sizeable thorn in the side for UPA-2.

The government hopes the farm sector significantly improves on 2012’s 1.8% growth with R Rangarajan, chairman of the PM’s economic advisory council, saying a normal monsoon could even yield a 3.4% growth.

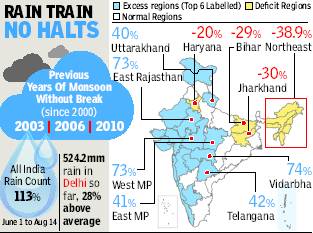

Monsoons without a break

Non-stop monsoon marches on

Amit Bhattacharya TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/16

One or two periods of a break in monsoon — defined as three straight days of very low rain activity across central India — are common during the rainy season. Since 2000, there have only been three years when there was no monsoon break. And all three years coincided with plentiful rains.

“Two months of monsoon activity without a break is rather rare. It’s an indication of agood monsoon,” said M Rajeevan, senior weather scientist at the earth sciences ministry.

At least four factors have worked in favour of the monsoon in 2013. The first good sign was an absence of El Nino — an anomalous rise in ocean surface temperatures in the east Pacific that is linked to monsoon failure in India.

Currently, weak La Nina conditions exist in the Pacific, which is the opposite of El Nino and is known to help the monsoon here.

“Then, typhoons breaking out over the south Pacific this season have also helped because these have generally moved in a direction that reinforces the Indian monsoon. This is consistent with the weak La Nina conditions,” said Rajeevan.

More importantly, what has helped sustain the rains — and distribute it more or less evenly across the region — has been a series of low pressure formations over the Bay of Bengal that have travelled westwards at regular intervals.

“There have been an unusually high number of low pressure systems, along with cyclonic circulation over land. These have nurtured the monsoon this year, especially in the interior regions of south and central India,” said Pai.

Lastly, Pai said a strong Arabian Sea branch of the monsoon first helped accelerate the rain coverage over the country, and also brought good rains over the west coast.

2015: Monsoons in India

The Times of India, May 30 2015

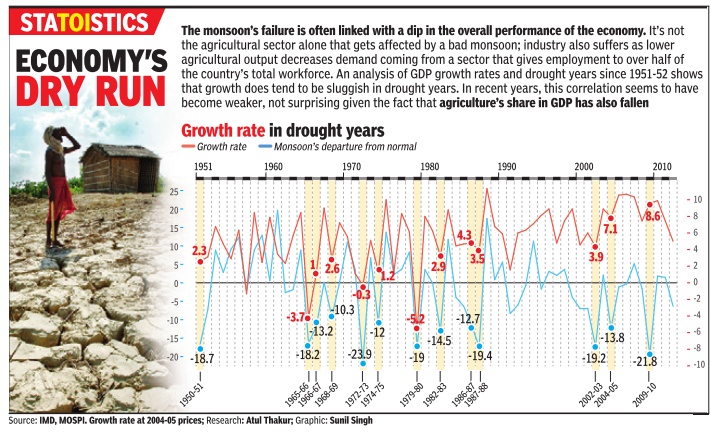

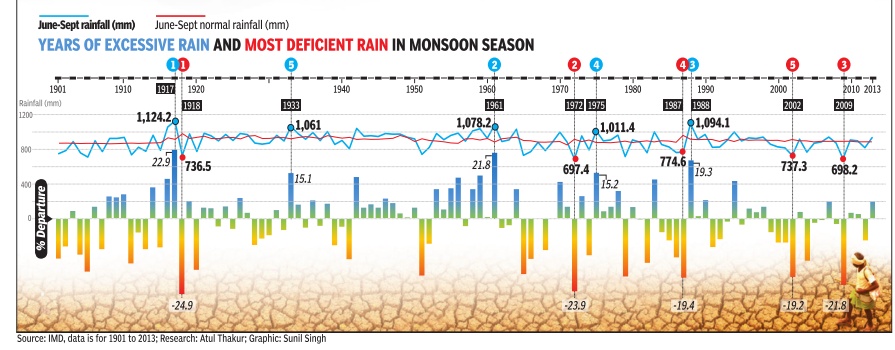

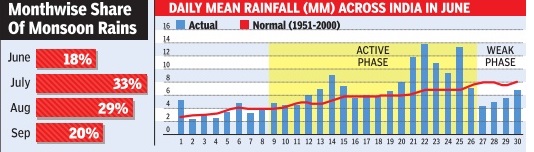

India receives most of the rainfall in four monsoonal months-June, July, August and September. The Met department defines normal monsoon to be 96 to 104% of the long period average, usually the average monsoon over 30 years. If the rainfall deficiency is more than 10%, it would typically be called a drought year. Last year's monsoon was deficient by 12%. This year's monsoon rainfall is predicted to be 93% of the average. If this year's monsoon deficiency crosses 10%, it will be one more year of drought, making it two successive years of drought, an event that has happened only three times in the past 113 years (1904-05, 1965-66 and 1986-87). In 1917, monsoon exceeded normal by the highest percentage (22.9) in 113 years. In 1918, monsoon was deficient by 24.9%, the highest deficiency for this period

2015

The Times of India, Aug 02 2015

Amit Bhattacharya, Vishwa Mohan & Neha Madaan

Dry days: 17% rain deficit in July

After a wet June, when other systems had countered the adverse effects of El Nino, monsoon took a drier turn in July and the month ended with a countrywide rain deficit of 17%. However, kharif sowing remained robust, boost ed by good rain spells in sev eral parts of the country . With the dip in rains monsoon's performance in the first half of the season -June 1 to July 31 -was 5% below the long term average June had a monsoon surplus of 16%.

Heavy rains in Gujarat Rajasthan, West Bengal Jharkhand and parts of cen tral India masked the fact that July this year was the driest since 2002 in terms of average rainfall across the country . The month started on a weak note and rains re mained below par till July 19, except for a brief four day period from the 9th.

But there were several redeeming features. “The rainfall, although weak, has been fairly well distributed across most parts of the country ,“ said D Sivananda Pai, head of India Meteoro logical Department's long range forecasting section.

However, some distress zones of low rainfall have started emerging. Rains were consistently weak through July in south India as well as subdivisions such as Marath wada and Madhya Maharash tra. From July 1 till 29, the southern peninsula recorded the highest rainfall deficien cy in the country , at 46%.

“We had forecast an 8% rainfall deficit for July , but it has turned out to be more. A typical feature this year has been that most rain-causing disturbances have been com ing from the east. Indian Ocean's monsoon circulation has been weak, which means that the monsoon pulses are not progressing from the south, which has caused a significant rainfall deficiency in the southern parts,“ a Met department official said.

However, rains in the north, most parts of central India and many regions of the east were close to normal.This is reflected in the kharif crop sowing figures. The overall sown area has, so far, been far ahead of the corresponding figures last year, which was a bad monsoon year.

The area under kharif as on Friday (July 31) was still less than what was reported at this time in 2013, when rains were plentiful in the monsoon months. As compared to 819.99 lakh hectares as on August 2, 2013, the kharif sown area this year was 764.28 lakh hectares as on July 31.

The monsoon is predicted to be active through the first week of August, raising hopes that the net sown area would grow in the coming days.

Several agencies, howev er, have predicted a relatively dry period in the country after the first week of August when the monsoon could go into a break, increasing the overall rain deficit.

In its monsoon update in June, IMD had forecast a 10% rain deficit in August. The department will issue another update for the second half of the season in a day or two. It had in June predicted a drought year, with overall seasonal rains at 12% below normal. Meanwhile, private forecaster Skymet downgraded its prediction for the season from 102% to 98%, still staying within the normal range.

PM explores ways on sugar exports

M Modi called for renewed P efforts to raise ethanol blending of fuel and exploring all possibilities for sugar exports as he brainstormed with key ministers and officials to resolve the problems faced by the sector.He reviewed the progress with regard to the Rs 6000 crore incentive package approved by the Centre in June and emphasized that the farmers' interest be kept foremost at all times.

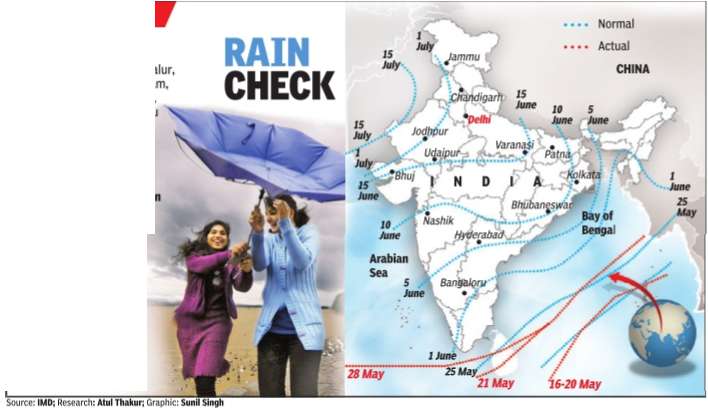

Monsoon cycle

The Times of India , Jun 02 2015

If after May 10, 60% of 14 stations -Minicoy, Amini, Thiruvananthapuram, Punalur, Kollam, Allapuzha, Kottayam, Kochi, Thrissur, Kozhikode, Thalassery, Kannur, Kudulu and Mangalore -report rainfall of 2.5 mm or more for two consecutive days, the onset of the monsoon is declared on the second day. Normally, the monsoon sets in over Kerala around June 1 and then advances northwards. By June 5, it goes past half of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh and crosses Maharashtra by the 10th.It covers significant portions of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh by June 15 and the entire country by June-end.

Monsoon break

A monsoon break — a period when rain activity comes to a stop in most of central India, the region where the monsoon trough is formed — is a common occurrence during the season. “The monsoon has been active without a break since mid-June. This does not happen often and is a reason why the rains were higher than the predicted 101% of LPA for July,” said D Sivananda Pai, IMD’s lead monsoon forecaster. (By Amit Bhattacharya)

Monsoons: date of arrival in various parts of India

See accompanying chart for Delhi

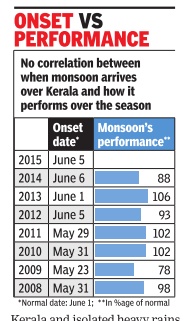

Years in which the monsoon arrived early

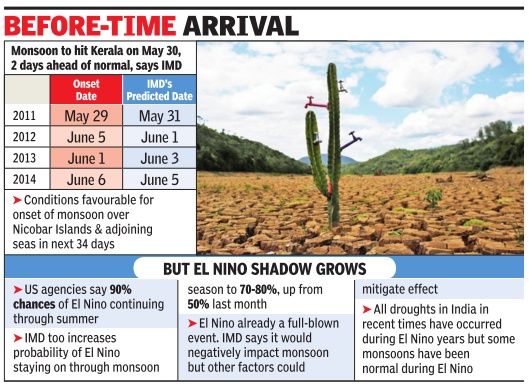

Droughts in India

Drought-proofing in India: 1960s-90s

Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar

Drought not a big calamity in India anymore

The monsoon has failed badly this year as it did in 1965.But its little more than an inconvenience this year,whereas in 1965 it was a monstrous calamity.The drought-proofing of India is a success story,but one widely misunderstood. India in the 1960s was pathetically dependent on US food aid.Even in the bumper monsoon year of 1964-65,food aid totalled 7 million tonnes,over one-tenth of domestic production.Then India was hit by twin droughts in 1965 and 1966.Grain production crashed by one-fifth.Only unprecedented food aid saved India from mass starvation.Jawaharlal Nehru talked big about self-sufficiency.Yet he led India into deep dependence on foreign charity.The 1966 drought drove India into a ship-to-mouth existence.Hungry mouths could be filled only by food aid,which reached a record 10 million tonnes. Foreign experts opined that India could never feed itself.William and Paul Paddock wrote a best-seller titled Famine 1975,arguing that the world was running out of food and would suffer global famine by 1975.They said aid-givers couldnt possibly meet the food needs of high-population countries like India.So,the limited food surpluses of the West should be conserved for countries capable of being saved.Countries incapable of being saved,like India,should be left to starve,for the greater good of humanity.Indians were angered and horrified by the book,yet it was widely applauded in the West.Environmentalist Paul Ehrlich,author of The Population Bomb,praised the Paddock brothers sky-high for having the guts to highlight a Malthusian challenge. The US was never happy with Indias non-alignment.President Johnson made Indian politicians and officials beg repeatedly for more food.This prevented mass starvation,but left Indians writhing with humiliation. Then came the green revolution.This,it is widely but inaccurately believed,raised food availability and ended import dependence.Now,the green revolution certainly raised yields,enabling production to increase,even though acreage reached a plateau.But it did not improve foodgrain availability per person.This reached a peak of 480 grams per day per person in 1964-65,a level that was not reached again for decades.Indeed,it was just 430 gm per day per person last year.Per capita consumption of superior foodsmeat,eggs,vegetables,edible oilsincreased significantly over the years.But poor people could not afford superior foods. How then did the spectre of starvation vanish Largely because of better distribution.Employment schemes in rain-deficit areas injected purchasing power where it was most needed.The slow but steady expansion of the road network helped grain to flow to scarcity areas.The public distribution system expanded steadily.Hunger remained,but did not escalate into starvation.By the 1990s,hunger diminished too. Second,the spread of irrigation stemmed crop losses.The share of the irrigated area expanded from roughly one-third to 55% of total acreage.Earlier,most irrigation was through canals,which themselves suffered when droughts dried up reservoirs.But after the 1960s,tubewell irrigation rose exponentially,and now accounts for four-fifths of all irrigation.Tubewells are not affected by drought. More important,tubewells facilitated rabi production in areas with little winter rain.Once,the rabi crop was just one-third the size of the kharif crop.Today both are equal.This explains why in 2009,which witnessed one of the worst monsoon failures for a century,agricultural production actually rose 1%: good rabi production offset the slump in kharif production. However,arguably the biggest form of drought proofing lies outside agriculture.Rapid GDP growth has dramatically raised the share of industry and services.Agriculture accounted for 52% of GDP in 1950,and for 29.5% even in 1990.This is now down to just 14%.Even if one-twentieth of this is lost to drought,it will be less than 1% of GDP. Back in the 1960s,India couldnt afford to import food,and depended on charity.But today GDP is almost $2 trillion,exports of goods and services exceed $300 billion and forex reserves are $280 billion.Even if we had to import 10 million tonnes of wheat at todays high prices,the cost,$3 billion,would be easily affordable.In fact,no imports are needed: government food stocks exceed 80 million tonnes. This is the real reason that droughts have ceased to be calamities.Foodgrain availability remains as low as in the 1960s,despite the green revolution.But rapid GDP growth,by hugely boosting the share of services and industry in GDP,has made agriculture a relative pygmy,greatly reducing the economys monsoon dependence.There remains a catch: a drought may no longer mean mass starvation,but still means food inflation.

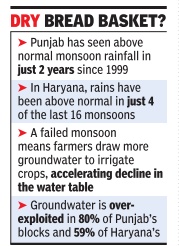

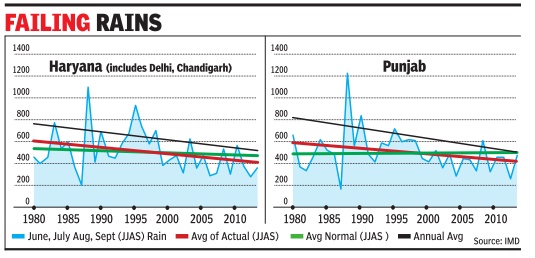

Monsoons in Punjab, Haryana

16-year trend of poor monsoon in Punjab, Haryana

Amit Bhattacharya New Delhi The Times of India Sep 22 2014

India's bread basket states of Punjab and Haryana received just around half the normal rainfall this monsoon season. But more worryingly , this year's rain deficit is not an isolated event. The two key agricultural states have been getting below par rainfall for the past 16 years.

Met department figures reveal Punjab has seen above normal monsoon rainfall in just two years since 1999. The last time that happened was seven monsoons ago, in 2008.The stats are similar for Haryana, where rains have been above normal in just four of the last 16 monsoons.

Experts are divided over why rains have been consistently failing in the region but the trend has dire implications for agriculture, which relies heavily on groundwater. The two states are among the most exploited regions in the world for groundwater.

Deficient rains add another dimension to the crisis.Groundwater mainly de pends on rainfall for recharge. So, less rain means less groundwater availability .A failed monsoon also means farmers draw more ground water to irrigate their crops, particularly paddy , accelerating the fall of the water table.

At TOI's request, Prof Krishna AchutaRao from IIT Delhi's Centre for Atmospheric Sciences plotted the annual and seasonal rainfall in the two states since 1980.The rain stats were obtained from the India Meteorological Department. A linear graph reveals a disturbing trend of decreasing rains in the bread basket of India. It shows average annual rainfall in Punjab falling during this period from just over 800mm in 1980 to less than 600mm in 2014 — a drop of roughly 200mm. Haryana’s annual average shows a similar drop, from around 780mm in 1980 to less than 580mm at present.

For monsoon season rainfall, Punjab has seen a drop of nearly 120mm, from an average of around 600mm in 1980 to roughly 480mm this year.

In Haryana, it’s down from more than 600mm to around 470mm during the same 35year period.

“The long term decrease in rainfall is apparent from the graph,” says AchutaRao, “although the rain statistics for the 1980s show very high variation.” But what’s not so apparent is the cause of the decline.

D Sivananda Pai, head of long range forecasting at IMD Pune, believes the drop is part of natural variability which will get reversed in time.

“Indian monsoon is passing through a low rainfall epoch since the 1990s. The drop in rainfall in this region could be part of that phenom enon,“ says Pai.

The story may not be that straightforward, says AchutaRao, who is coordinating multi-agency research into the Indian monsoon.