Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: Biography

(→Early life) |

(→Early life) |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

Nonetheless, Nehru's tribute to his former colleague read, “He was not only brave but had deep love for freedom.He believed, rightly or wrongly, that whatever he did was for the independence of India.... Although I personally did not agree with him... nobody can doubt his sincerity .He struggled throughout his life for the independence of India, in his own way .“ | Nonetheless, Nehru's tribute to his former colleague read, “He was not only brave but had deep love for freedom.He believed, rightly or wrongly, that whatever he did was for the independence of India.... Although I personally did not agree with him... nobody can doubt his sincerity .He struggled throughout his life for the independence of India, in his own way .“ | ||

| + | |||

| + | =The disappearance of Netaji= | ||

| + | [[File: Portrait of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.jpg|Picture courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Netaji-The-Saint-07092015010013 ''The Times of India''], Sep 07 2015|frame|500px]] | ||

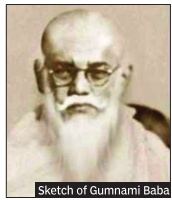

| + | [[File: Sketch of Gumnami Baba.jpg|Picture courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Netaji-The-Saint-07092015010013 ''The Times of India''], Sep 07 2015|frame|500px]] | ||

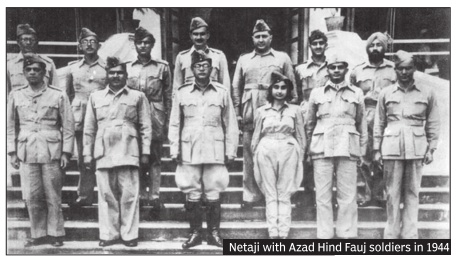

| + | [[File: Netaji with Azad Hind Fauj soldiers in 1944.jpg|Picture courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Netaji-The-Saint-07092015010013 ''The Times of India''], Sep 07 2015|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Netaji-The-Saint-07092015010013 ''The Times of India''], Sep 07 2015 | ||

| + | |||

| + | It's one of the greatest mysteries of modern india: was gumnami baba, also known as the ascetic of up's faizabad, actually netaji subhas chandra bose? subhro niyogi, saikat ray and a team of reporters track down some people who actually interacted with him and are convinced that it was none other than the charismatic leader himself, living under an assumed identity. read on to find out what they have to say | ||

| + | |||

| + | A moment that lasted a fraction of a second 33 years ago is etched so vividly in Sura jit Dasgupta's memory that a mere recollection triggers a myriad emotions. Dasgupta's facial muscles twitch, lips quiver and eyes turn misty as he strives to utter something, stutters and then gives up. | ||

| + | After several minutes of internal strife, Dasgupta composes himself. “He was seated before me like every day when I had an urge to see him. I stole a glance and was so dazzled by the glow that emanated from within that I had to immediately lower my gaze. It is a sight I will never forget,“ he mumbles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The “he“ Dasgupta refers to was Bhagwanji, an ascetic in Faizabad, UP , who very few “knew“ to be Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. Here was the man who had been pronounced dead 37 years ago, a death millions refused to believe. Many felt he would return to India one day to finally solve one of the most baffling mysteries of modern times. And there he was! “Netaji's associate and our guru, Sunil Gupta, had been visiting Bhagwanji for two decades. In the initial years, it was very secretive. He wouldn't disclose where he was going. All that we knew was that he had some very important mission. Later, he cryptically said: `Contact has been established'. I knew at once he was referring to Netaji. I was thrilled. In the years that followed, I would accompany Gupta till the station as he took a train twice a year to travel to Neemsar and later Faizabad, once during Durga Puja and again on January 23, Netaji's birthday . It was much later, in 1982, that Gupta decided it was finally time we could be let into the exclusive circle, and we travelled to Faizabad to meet Bhagwanji,“ Dasgupta recalls. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It was Netaji's elder brother, Suresh Chandra Bose, who had tasked Gupta with exploring every news and rumour that surfaced on Netaji's return to India. Gupta faithfully went to Shaulmari and other places where it was rumoured Netaji had returned in the guise of an ascetic. He was disappointed on each occasion, till he finally met Bhagwanji at Neemsar in 1962. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A few ground rules were laid before Dasgupta's first meeting; the most important being not to look at Bhagwanji. He generally communicated with a short curtain drawn between him and the visitors that hid his face. That is how Dasgupta met him as well. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “We would go to his house every day , have breakfast and then go to shop for the day's meals. While Saraswati Devi would cook, we would discuss world politics.After lunch, it could be about theology , music, even metaphysics. Sometimes, the discussions went on till the wee hours next morning. We would sit transfixed, listen with rapt attention and take down notes.He predicted the disintegration of USSR that was unthinkable then, talked about the mess in the Vietnam War. He even remarked that communism would die in the place of its birth. During the Bangladesh Liberation War, he followed the developments keenly and we believe he even passed on strategic instructions that helped decide the war,“ Dasgupta says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the first two-three days, Bhagwanji trusted that the youths would follow the rules, and stopped drawing the curtain. It was on one of these days Dasgupta was seized by the irresistible desire to steal a glance at the person hero-worshipped across Bengal. And what a sight it was! “There was no mistaking it was Netaji. His hair had thinned, much more than what we were used to seeing in his photographs. He had a flowing beard. But the features were exactly the same. Only , he had aged. The eyes were so powerful I had to turn away immediately . I realized then that the patriot our parents and we had worshipped since we were kids had reached a higher plane of existence. He had become a mahatma,“ he recalls. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rita Banerjee of Faizabad, too, refers to a “bright light“ emanating from Bhagwanji. “The aura was so intense that I could not establish eye contact with him,“ says Rita, whom Bhagwanji called “Phoolwa Rani“ and her husband “Bachha“. Gyani Gurjeet Singh Khalsa, the chief priest of Gurdwara Brahamakund Sahib that overlooks the raging Saryu river, recounts a similar experience when he saw Bhagwanji face-to-face. “I was a 17-year-old when I saw him. The radiance on his face was astounding. It cannot be explained in words,“ he recounts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dasgupta, who is now 64, and some others who are convinced that Bhagwanji was Netaji, are waging a silent legal battle against the Indian government to extract the truth and discredit a lie they claim has been propagated for seven decades. In later years, Bhagwanji talked about the escape to USSR via Diren in Manchuria after a “concocted air crash“. He talked vividly about how prison camps functioned in Siberia. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dasgupta is among the very few alive to have met Bhagwanji. Bijoy Nag, a former auditor at a private firm, is another. Though he never looked at Bhagwanji, he can recall each meeting with amazing clarity . “On my first visit, I touched his feet while he remained behind a curtain. Blessing me, he said: `Your dream is now a reality'. I was 31 and thrilled,“ recalls Nag, now 76. In all, he had met the ascetic 14 times between 1970 and 1985, and each meeting was memorable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most of Dasgupta's visits were when the ascetic was living in Purani Bustee.But it was at Brahma Kund (Ayodhya) where Bhagwanji stayed for a few months between 1975 and 1976 that Nag was in closest proximity with him. “I stayed in the room next to his. I could have looked at him any time if I wished because by then, the curtain had been drawn.He had only instructed us not to look at him and we didn't disobey him,“ says Nag, who had on Bhagwanji's request collected and delivered photographs of Netaji's mother, father and school teacher. | ||

| + | |||

| + | More stoic than Dasgupta, Nag is in control of his emotions but there is no mistaking the glimmer in his eyes when the subject is discussed. “Though I didn't look at him, I don't have an iota of doubt it was Netaji speaking to me. It is an unshakeable truth,“ he says with such definitiveness that one realizes it is backed by absolute conviction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It was because of his aunt Lila Roy -who had been in constant touch with Netaji between 1922 and January 1941 -that Nag got the opportunity to meet Bhagwanji. It was Sketch of INA secret service agent Pabitra Mohan Roy who told Lila about Bhagwanji in December 1962 after another Netaji associate, Atul Sen, broke the news on his return from Neemsar. His meeting Bhagwanji had been sheer providence. Sen, who had contested the legislative seat from Dhaka in the 1930s on Netaji's insistence and won, was in 1962 travelling to various places in UP on “change“ on doctor's advice. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In April, he reached Neemsar, a pilgrimage site near Lucknow. It is here that he heard from locals about a Bengali mahatma who lived in an abandoned Shiva temple. Sen's curiosity was piqued and d went to meet the ascetic. He finally met d him after several attempts -and instant ly knew it was Netaji. Over the next few n days, he met Bhagwanji many times. | ||

| + | |||

| + | . An ecstatic but cautious Atul Sen re) turned to Kolkata in 1962 and disclosed s the news to Pabitra Mohan Roy and his torian RC Majumdar. Sen also wrote to e PM Jawaharlal Nehru on August 28, 1962. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Netaji is alive and is engaged in spiritual e practice somewhere in India... From the talks I had with him, I could understand that he is yet regarded as enemy No. 1 of Allied powers and that there is a secret protocol that binds the Indian government to deliver him to Allied `justice' if found alive. If you can assure me otherwise, I may try to persuade him to return to open life,“ he wrote. In the reply dated August 31, 1962, Nehru denied the existence of any such protocol. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lila, meanwhile, resolved to serve Bhagwanji till her last day. From 1963 till her death in 1970, she would send money and sundry items to him every month through emissaries. Bhagwanji was fond of typical Bengali dishes like ghonto, sukto and keema. During his birthday celebrations, a closed-door affair with some family members and close acquaintances, delicacies served included mishti doi and khejur gur payesh. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It wasn't just people from Bengal who were meeting Bhagwanji. From December 1954 to April 1957, UP CMs Sampurnanand and Benarasi Dasgupta were in constant touch with Bhagwanji.Their letters as well as those from former railway minister Ghani Khan Chowdhury and other important leaders were found in Bhagwanji's belongings that are now in Faizabad Treasury . | ||

=The concerned panels= | =The concerned panels= | ||

Revision as of 14:33, 9 September 2015

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

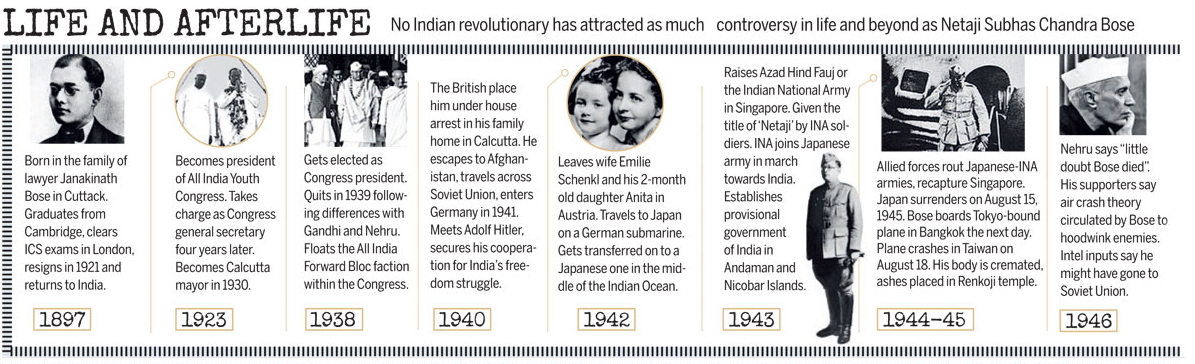

Early life

Mridula Mukherjee

April 9, 2015

Unlike Nehru, Netaji believed that authoritarian rule was essential for achieving radical social goals

A misguided patriot

Subhas Chandra Bose fulfilled a promise to his father that he would sit for the Indian Civil Service examination in London. He secured the fourth position in 1920 but then went on to fulfil his own wish. He resigned from the coveted service the following year, saying "only on the soil of sacrifice and suffering can we raise our national edifice". Returning to India, he plunged into the national struggle and by 1923, was secretary of the Bengal State Congress and president of All India Youth Congress.

By 1927, he emerged, along with Jawaharlal Nehru, as leader of the new youth movement, which came into its own by playing a major role in the anti-Simon Commission agitation which swept India that year. He was also the chief organiser of the Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress (INC) in December 1928, which demanded that the goal of the Congress be changed to 'Purna Swaraj' or 'Complete Independence'.

Imprisonment in the Civil Disobedience movement followed by bad health in 1932 took him to Europe where he observed European politics, particularly Fascism under Mussolini and Communism in the Soviet Union. He was impressed by both and believed that authoritarian rule was essential for achieving radical social goals.

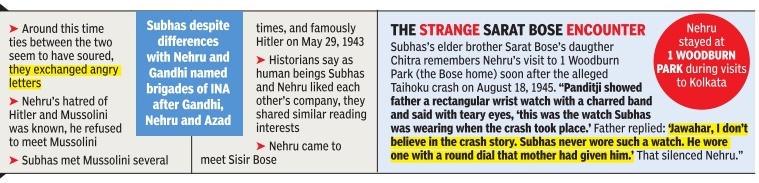

In fact, it is in this period that the political views of Nehru and Bose begin to diverge sharply, especially on the issue of Fascism and Nazism. Nehru was so vehemently opposed to Fascism that he refused to meet Mussolini even when the latter sought him out, whereas Bose not only met Mussolini but was impressed by him. Nehru was sharply critical of the growing danger to the world from the rise of Hitler. Bose, on the other hand, never expressed that kind of aversion to Fascism, and was quite willing to seek the support of Germany and later Japan against Britain. However, he was not happy with the German attack on Soviet Union in 1941, and that was one reason why he left Germany for Japan. For Bose, Socialism and Fascism were not polar opposites, as they were for Nehru.

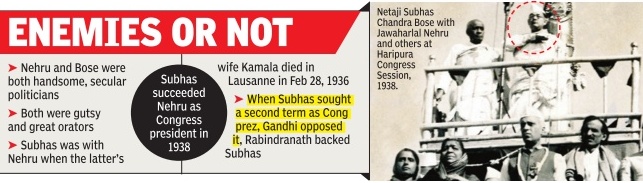

In 1938, Bose was unanimously elected, with the full support of Gandhiji, as Congress president for the Haripura session. But the next year, he decided to stand again, this time as a representative of militant and radical groups. An election ensued which Bose won by 1,580 to 1,377 votes, but the battle lines were drawn. The challenge he threw by calling Gandhian leaders rightists who were working for a compromise with the British Government was answered by 12 members of the Working Committee resigning and asking Bose to choose his own committee. Nehru did not resign with other members but he was unhappy with Bose's casting of aspersions on senior leaders. He tried his best to mediate and persuade Bose not to resign.

The crisis came to a head at Tripuri in March 1939, with Bose refusing to nominate a new Working Committee and ultimately resigning. The clash was of policy and tactics. Bose wanted an immediate struggle led by Gandhiji, whereas Gandhiji felt the time was not ripe for struggle.

Having burnt his boats with the Congress, Bose went first to Germany in January 1941 and then to Japan in 1943 to seek help in the struggle against their common enemy, Britain. He finally went to Singapore to take charge of the Indian National Army (INA) which had been formed by Mohan Singh in 1941 from Indian prisoners of war captured by the Japanese. The INA was clear that it would go into action only on the invitation of the INC; it was not set up as a rival centre of power. Bose made this more explicit when on July 6, 1944, in a broadcast on Azad Hind Radio addressed to Gandhiji, he said, "Father of our Nation! In this holy war of India's liberation, we ask for your blessing and good wishes".

The INA was allowed to participate with the Japan Army only in the Imphal Campaign, and the experience was none too happy-discriminatory treatment, a painful retreat and surrender to the British. Captured soldiers were brought back to India and threatened with court martials. The Congress, led by Nehru, demanded leniency, calling the INA men patriots, albeit misguided. There was a wave of sympathy across the country, and Nehru, Bhulabhai Desai, Sapru, Katju and Asaf Ali donned lawyer's robes to defend the INA leaders in the Red Fort trials.

Meanwhile, Subhas Bose succumbed to burn injuries received in a plane crash in Taiwan on August 18, 1945. What Nehru said of the INA soldiers may well be said of him: a patriot, albeit misguided.

‘Samyavad': a mix of Fascism and Communism

The Times of India, Apr 20 2015

Netaji wanted dictatorship for 20 yrs

Manimugdha Sharma

Recent allegations of the Nehru government snooping on the relatives of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose have led to conspiracy theorists propounding that Netaji was a greater patriot than India's first Prime Minister. What is conveniently ignored is his treaty with the evil Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan in raising the INA. By his own admission, in his book Indian Struggle (published in 1935 in London), Netaji said India needed a political system that was a mix of Fascism and Communism: something he called `samyavad'. Netaji made a special trip to Rome in 1935 to present a copy of his book to the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, whom he greatly admired, and whose ideals he followed. Bose's reactionary views naturally brought him in conflict with the pacifist leaders of Congress, most notably Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Nehru. But their friction didn't occur in 1935; it happened much earlier.

Bose had organized the annual session of the Indian National Congress in 1928 in Calcutta. There, he organized a guard of honour in full military style: over 2,000 volunteers were drilled in military fashion and arranged into battalions; half of them wore military uniforms with “officers“ wearing metal epaulettes.

For himself, Bose got a British military officer's dress tailored by Calcuttabased British firm, Harman's, complemented by an aiguillette and a field marshal's baton. He also assumed the title of general officer commanding, much to the chagrin of Gandhi, who described the whole thing as `Bertram Mills circus'. But Bose's love for militarism continued.

In 1938, at the 51st session of the Congress at Haripura, Bose was the president. He organized for himself a grand ceremony that was no less than the march of a triumphant ancient Indian king returning from conquest. He is said to have entered the venue in a chariot drawn by 51 bullocks, accompanied by 51 girls in saffron saris, after a two-hour procession through 51 gates that also had 51 brass bands playing. He would do similar shows in Southeast Asia when he helmed the INA and Indian Independence League.

In October 1943, Bose announced the formation of the provisional government of free India , assuming the titles of head of state, prime minister, and minister for war and foreign affairs. He demanded total submission from his countrymen; anybody who opposed him, his army or government could be executed.

The INA proclamation stated: “If any person fails to understand the intentions of the Provisional Government of Azad Hind and the Indian National Army , or of our Ally , the Nippon Army , and dares to commit such acts as are itemized hereunder which would hamper the sacred task of emancipating India, he shall be executed or severely punished in accordance with the Criminal Law of the Provisional Government of Azad Hind and the INA or with the Martial Law of the Nippon Army .“

In a speech the same year in Singapore, Bose spoke about India needing a ruthless dictator for 20 years after liberation. The now-defunct Singapore daily , Sunday Express, printed his speech in which he said, “So long as there is a third party , ie the British, these dissensions will not end. They will disappear only when an iron dicta tor rules over India for 20 years. For a few years at least, after the end of British rule in India, there must be a dictatorship...No other constitution can flourish in this country and it is so to India's good that she shall be ruled by a dictator, to begin with.“

By this time, Netaji seems to have preferred Nazism more than Fascism. In a speech to Tokyo University students in 1944, Netaji said India needs a philosophy that “should be a synthesis between National Socialism (Nazism) and Communism“. Around this time, of course, any form of cordiality that existed between Bose and Nehru had evaporated.

Nonetheless, Nehru's tribute to his former colleague read, “He was not only brave but had deep love for freedom.He believed, rightly or wrongly, that whatever he did was for the independence of India.... Although I personally did not agree with him... nobody can doubt his sincerity .He struggled throughout his life for the independence of India, in his own way .“

The disappearance of Netaji

The Times of India, Sep 07 2015

It's one of the greatest mysteries of modern india: was gumnami baba, also known as the ascetic of up's faizabad, actually netaji subhas chandra bose? subhro niyogi, saikat ray and a team of reporters track down some people who actually interacted with him and are convinced that it was none other than the charismatic leader himself, living under an assumed identity. read on to find out what they have to say

A moment that lasted a fraction of a second 33 years ago is etched so vividly in Sura jit Dasgupta's memory that a mere recollection triggers a myriad emotions. Dasgupta's facial muscles twitch, lips quiver and eyes turn misty as he strives to utter something, stutters and then gives up. After several minutes of internal strife, Dasgupta composes himself. “He was seated before me like every day when I had an urge to see him. I stole a glance and was so dazzled by the glow that emanated from within that I had to immediately lower my gaze. It is a sight I will never forget,“ he mumbles.

The “he“ Dasgupta refers to was Bhagwanji, an ascetic in Faizabad, UP , who very few “knew“ to be Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. Here was the man who had been pronounced dead 37 years ago, a death millions refused to believe. Many felt he would return to India one day to finally solve one of the most baffling mysteries of modern times. And there he was! “Netaji's associate and our guru, Sunil Gupta, had been visiting Bhagwanji for two decades. In the initial years, it was very secretive. He wouldn't disclose where he was going. All that we knew was that he had some very important mission. Later, he cryptically said: `Contact has been established'. I knew at once he was referring to Netaji. I was thrilled. In the years that followed, I would accompany Gupta till the station as he took a train twice a year to travel to Neemsar and later Faizabad, once during Durga Puja and again on January 23, Netaji's birthday . It was much later, in 1982, that Gupta decided it was finally time we could be let into the exclusive circle, and we travelled to Faizabad to meet Bhagwanji,“ Dasgupta recalls.

It was Netaji's elder brother, Suresh Chandra Bose, who had tasked Gupta with exploring every news and rumour that surfaced on Netaji's return to India. Gupta faithfully went to Shaulmari and other places where it was rumoured Netaji had returned in the guise of an ascetic. He was disappointed on each occasion, till he finally met Bhagwanji at Neemsar in 1962.

A few ground rules were laid before Dasgupta's first meeting; the most important being not to look at Bhagwanji. He generally communicated with a short curtain drawn between him and the visitors that hid his face. That is how Dasgupta met him as well.

“We would go to his house every day , have breakfast and then go to shop for the day's meals. While Saraswati Devi would cook, we would discuss world politics.After lunch, it could be about theology , music, even metaphysics. Sometimes, the discussions went on till the wee hours next morning. We would sit transfixed, listen with rapt attention and take down notes.He predicted the disintegration of USSR that was unthinkable then, talked about the mess in the Vietnam War. He even remarked that communism would die in the place of its birth. During the Bangladesh Liberation War, he followed the developments keenly and we believe he even passed on strategic instructions that helped decide the war,“ Dasgupta says.

After the first two-three days, Bhagwanji trusted that the youths would follow the rules, and stopped drawing the curtain. It was on one of these days Dasgupta was seized by the irresistible desire to steal a glance at the person hero-worshipped across Bengal. And what a sight it was! “There was no mistaking it was Netaji. His hair had thinned, much more than what we were used to seeing in his photographs. He had a flowing beard. But the features were exactly the same. Only , he had aged. The eyes were so powerful I had to turn away immediately . I realized then that the patriot our parents and we had worshipped since we were kids had reached a higher plane of existence. He had become a mahatma,“ he recalls.

Rita Banerjee of Faizabad, too, refers to a “bright light“ emanating from Bhagwanji. “The aura was so intense that I could not establish eye contact with him,“ says Rita, whom Bhagwanji called “Phoolwa Rani“ and her husband “Bachha“. Gyani Gurjeet Singh Khalsa, the chief priest of Gurdwara Brahamakund Sahib that overlooks the raging Saryu river, recounts a similar experience when he saw Bhagwanji face-to-face. “I was a 17-year-old when I saw him. The radiance on his face was astounding. It cannot be explained in words,“ he recounts.

Dasgupta, who is now 64, and some others who are convinced that Bhagwanji was Netaji, are waging a silent legal battle against the Indian government to extract the truth and discredit a lie they claim has been propagated for seven decades. In later years, Bhagwanji talked about the escape to USSR via Diren in Manchuria after a “concocted air crash“. He talked vividly about how prison camps functioned in Siberia.

Dasgupta is among the very few alive to have met Bhagwanji. Bijoy Nag, a former auditor at a private firm, is another. Though he never looked at Bhagwanji, he can recall each meeting with amazing clarity . “On my first visit, I touched his feet while he remained behind a curtain. Blessing me, he said: `Your dream is now a reality'. I was 31 and thrilled,“ recalls Nag, now 76. In all, he had met the ascetic 14 times between 1970 and 1985, and each meeting was memorable.

Most of Dasgupta's visits were when the ascetic was living in Purani Bustee.But it was at Brahma Kund (Ayodhya) where Bhagwanji stayed for a few months between 1975 and 1976 that Nag was in closest proximity with him. “I stayed in the room next to his. I could have looked at him any time if I wished because by then, the curtain had been drawn.He had only instructed us not to look at him and we didn't disobey him,“ says Nag, who had on Bhagwanji's request collected and delivered photographs of Netaji's mother, father and school teacher.

More stoic than Dasgupta, Nag is in control of his emotions but there is no mistaking the glimmer in his eyes when the subject is discussed. “Though I didn't look at him, I don't have an iota of doubt it was Netaji speaking to me. It is an unshakeable truth,“ he says with such definitiveness that one realizes it is backed by absolute conviction.

It was because of his aunt Lila Roy -who had been in constant touch with Netaji between 1922 and January 1941 -that Nag got the opportunity to meet Bhagwanji. It was Sketch of INA secret service agent Pabitra Mohan Roy who told Lila about Bhagwanji in December 1962 after another Netaji associate, Atul Sen, broke the news on his return from Neemsar. His meeting Bhagwanji had been sheer providence. Sen, who had contested the legislative seat from Dhaka in the 1930s on Netaji's insistence and won, was in 1962 travelling to various places in UP on “change“ on doctor's advice.

In April, he reached Neemsar, a pilgrimage site near Lucknow. It is here that he heard from locals about a Bengali mahatma who lived in an abandoned Shiva temple. Sen's curiosity was piqued and d went to meet the ascetic. He finally met d him after several attempts -and instant ly knew it was Netaji. Over the next few n days, he met Bhagwanji many times.

. An ecstatic but cautious Atul Sen re) turned to Kolkata in 1962 and disclosed s the news to Pabitra Mohan Roy and his torian RC Majumdar. Sen also wrote to e PM Jawaharlal Nehru on August 28, 1962.

“Netaji is alive and is engaged in spiritual e practice somewhere in India... From the talks I had with him, I could understand that he is yet regarded as enemy No. 1 of Allied powers and that there is a secret protocol that binds the Indian government to deliver him to Allied `justice' if found alive. If you can assure me otherwise, I may try to persuade him to return to open life,“ he wrote. In the reply dated August 31, 1962, Nehru denied the existence of any such protocol.

Lila, meanwhile, resolved to serve Bhagwanji till her last day. From 1963 till her death in 1970, she would send money and sundry items to him every month through emissaries. Bhagwanji was fond of typical Bengali dishes like ghonto, sukto and keema. During his birthday celebrations, a closed-door affair with some family members and close acquaintances, delicacies served included mishti doi and khejur gur payesh.

It wasn't just people from Bengal who were meeting Bhagwanji. From December 1954 to April 1957, UP CMs Sampurnanand and Benarasi Dasgupta were in constant touch with Bhagwanji.Their letters as well as those from former railway minister Ghani Khan Chowdhury and other important leaders were found in Bhagwanji's belongings that are now in Faizabad Treasury .

The concerned panels

Apr 12 2015 The Times of India

The Bose probes

Days after the Taihoku crash, rumours on whether Netaji had survived it began. Several panels have probed the matter

Figgess Report 1946

Found Bose died in Taihoku Military Hospital on Aug 18, 1945. Cause of death heart failure resulting from multiple burns and shock in crash near Taihoku airport. Cremated in Taihoku & ashes transferred to Tokyo

Shah Nawaz panel 1956

Khan was in the INA and the best-known defendant in the INA trials. Two members concluded Bose died in crash.Bose's brother Suresh declined to sign final report, wrote dissenting note saying the two withheld crucial evidence from him, that Nehru directed committee to infer death in crash

Khosla panel 1970

Retd CJ of Punjab HC GD Khosla tasked to probe Bose's “disappearance“ Concurred with reports, suggested political motives behind those denying crash

Mukherjee panel 1999-2005

Following a court order, SC judge MK Mukherjee headed team to probe death. Concluded there was secret plan to ensure Bose's safe passage to USSR with knowledge of the Japanese and Habibur Rahman. It observed ashes kept at the Renkoji Temple, reported to be Bose's, were of Ichiro Okura, a Japanese soldier. Govt rejected the findings

Bose’s files: a top secret

Apr 12 2015

Subhro Niyogi

Nehru spying on Netaji's kin is chicken feed compared to the explosive content of files still marked highly classified, says Netaji researcher and activist Anuj Dhar. “A recently declassified report of British intelligence unit MI5 shows it was receiving information on correspondence of Netaji's nephew Amiya Nath Bose from IB three months after Independence. This is worse than the Watergate scandal! Not just Amiya and Sisir, even Suresh Bose who was deputy magistrate in Dumka was spied on,“ said Dhar whose persistent RTIs led to the declassification of 91 of the 202 Netaji files.There are other top-secret files on Netaji, including 39 highly classified, with PMO.

Both UPA and NDA governments have turned down the declassification demand from Bose's family and activists, citing reasons incomprehensible. The Manmohan government claimed putting the information in public domain could endanger internal security, spark possible unrest in Bengal, and damage relations with foreign nations. Modi's government said India's relations with certain countries could be jeopardized if files were to be declassified. “In a PIL, we sought a judicial commission to review the two governments' stands. We want the courts to decide if there's veracity in the threat perception or is it only a cover-up,“ said Rajeev Sarkar, of Kolkata-based NGO India's Smile. The HC bench of Justices Asim Banerjee and S Prasad on April 9 gave the Centre two weeks to explain its final stand, asking government to explain why the Central Information Commission's (CIC) July 5, 2007, order that all 202 Netaji files be made public, hasn't been complied with.The court asked CIC for its opinion. Anuj Dhar and Sabyasachi Dasgupta were instrumental behind the CIC order.

Under scrutiny too are four missing files: on Netaji's whereabouts and on the ashes at Renkoji Temple that figured in a home ministry affidavit submitted to the Mukherjee Commission December 19, 2001. Replying to RTIs made on the files, the home ministry said in 2013 that the four files were not there. “Our interest is not whether Netaji died or didn't die in the alleged plane crash. What we want to know is how many Netaji files are there and why are they so secret,“ said Sarkar, fearing, like Dhar, that files are being destroyed to suppress India's history. “If truth is exposed, history will have to be rewritten,“ said Sarkar.

Not spying: Pawar

NCP chief Sharad Pawar gave IB a clean chit on the Netaji snooping episode, saying the agency did it for security, not espionage. “IB has to keep an eye on key people who work in public life. “Govt would be accountable if anything happened to Netaji's family. IB kept an eye on his family for their own safety,“ he said.

Keeping up with the bosses

The British CID had the two Bose family homes in Kolkata-1, Woodburn Park and the 38/2, Elgin Road-placed under surveillance at least since the 1930s. This was when the two Bose brothers, Sarat Chandra and his younger brother, Subhas Chandra, emerged at the forefront of the freedom movement in Bengal. The family had learned to live with the police glare. A CID officer once intercepted and duplicated a letter meant for Sarat Chandra but accidentally re-posted a copy. When he arrived at the Bose family doorstep to confess his mistake, the senior Bose told him to come back in a few days and recover it. Placed under house arrest in 1941, Netaji hoodwinked policemen and escaped the Elgin Road residence to land up in Nazi Germany. He was dubbed a fascist collaborator by the British who stepped up surveillance on his family members. As the declassified intercepts show, independent India's government was just as keen to spy on the family.

The IB has been routinely used by ruling parties to snoop on political opponents and even on their own family members. Former IB chief M.K. Dhar revealed in his 2005 book Open Secrets that PM Indira Gandhi ordered the IB to spy on Maneka Gandhi and her family because she suspected their political ambitions. But Netaji's two nephews, Sisir Kumar Bose and his brother Amiya Nath Bose, were political lightweights in the years they were snooped upon. They contested elections long after the papers show the IB had wound down its surveillance. Amiya Nath was elected as an MP from the Arambagh constituency on an All India Forward Bloc ticket only in 1968. Sisir Bose was elected to the West Bengal Legislative Assembly on a Congress ticket in 1987.

The IB seemed obsessed in knowing what the family was doing and who they were meeting. A series of handwritten messages show IB agents phoned in 'Security Control', as IB headquarters was called, to report on the family's movements. But it was in the intercepted family mail that the IB relied on to know what the family was thinking. Netaji figured heavily in their correspondence. What else would the family discuss? The letters were mostly about mundane family matters. Netaji's wife discusses their economic hardships, bringing up her daughter Anita and repairs at their flat in Vienna. The Boses in Kolkata sent them money to meet their expenses. The IB annotated and underlined parts of the letters that had names of people meeting Emilie Schenkl to show what they were interested in. An IB comment on a 1953 letter describes her as "the alleged wife of Sri Subhas Chandra Bose".

"Most mysterious and shocking," says Krishna Bose, 85, wife of the late Sisir Kumar Bose. "Why on earth would they want to tail us?" the former three-term Trinamool Congress Lok Sabha MP wonders as she slowly leafs through the declassified IB documents in 38/2, Elgin Road, now the Netaji Bhawan museum. She laughs at how particularly effective the surveillance was because the family never had a clue. "My husband told me he felt like he was being followed to the hospital and when he was boarding a tram...but that was during the British era."

The surveillance offers a rare insight into the workings of one of the world's oldest intelligence agencies. The letter intercepts almost exclusively focused on the Elgin Road post office from where the unsuspecting Bose family posted their missives to the out- side world. Family members recorded their scepticism over the Shah Nawaz inquiry committee appointed by the Nehru government in 1956 and their disappointment over the lack of recognition for their uncle.

"If you were in India today," Sisir Bose wrote to Netaji's wife in 1955, "you would get the feeling that in India's struggle two men mattered- (Mahatma) Gandhi and (Jawaharlal) Nehru. The rest were just extras."

All family letters were copied and some shared with two bright stars of the IB in the headquarters in Delhi in the 1950s-M.L. Hooja, who later headed the IB in 1968, and Rameshwar Nath Kao, who founded the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) in 1968. The man behind them all was Bhola Nath Mullick, Nehru's internal security czar who headed the IB for an unprecedented 16 years between 1948 and 1964.

That this surveillance was politically sensitive was a no-brainer. The 'Top Secret' and 'Very Secret' stamps on the files would restrict access to a very limited circle of officials. The files were stored in the steel cupboards of the IB's state headquarters in Kolkata's Pretoria Street, just a stone's throw away from the Bose residences.

"When Bengal's bhadraloks were regaled by a fictitious petty crime-solving Byomkesh Bakshi, real-life IB sleuths were performing feats that would give the CIA and KGB a run for its money," says Anuj Dhar, activist and author of India's Biggest Cover-Up that gives an investigative insight into the Netaji mystery.

The IB's surveillance was not restricted to Kolkata. A 1958 report from the Special Branch of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) in Madras reports the movements of Sisir Bose as he sets up the Netaji Research Bureau. A 1963 intercept has Amiya Nath's correspondence with ACN Nambiar, Netaji's former aide, then an Indian diplomat in Switzerland. The prying was not without irony. One of the senior IB officials reading the intercepts in Delhi was Nambiar's own nephew, A.C. Madhavan Nambiar.

British agency MI5

The Times of India Apr 12 2015

Documents reveal Nehru govt shared info on Netaji with MI5

Himanshi Dhawan

Not only did the Nehru government snoop on Netaji Subhas Bose but also shared confidential information with British intelligence agency MI5. Recently , declassified documents reveal India's Intelligence Bureau shared with MI5 a letter between close Netaji aide A C Nambiar and nephew Nambiar and nephew Amiya Nath Bose acquired through “secret censorship and even sought more information on the subject. The MI5 documents have become public at a time when Indian secret documents reveal that the late PM Jawarharlal Nehru had authorized surveillance on freedom fighter Netaji Bose's family including nephews Amiya Bose and Sisir Kumar Bose.

In a letter written on October 6, 1947, IB official S B Shetty sought “comments of MI5 security liaison of ficer K M Bourne posted in Delhi referencing a letter written by Nambiar to Ami ya Bose on August 19, 1947.“The attached is a letter dat ed the 19.8.47 from A C Nam biar, Limmatquai 80, Zurich, Switzerland to Amiya Nath Bose, 1 Woodburn Park, P O, Elgin Road, Calcutta. The letter was seen during secret censorship and was passed on. We should be grateful for your comments on the let ter, the note said.

In response, Bourne for warded Nambiar's letter en closing his request for fur ther information to MI5 director general the next day itself. Dated October 7, 1947, Bourne's letter says, “Any comments you may make on this letter will be appreciat ed. The letter could be about Bose's wife and daughter though the context is unclear.

Two letters, written just months after India's independence, are part of 2000 pages of MI5 declassified doc uments that were made pub lic last year. The documents were accessed by author Anuj Dhar who has spent 15 years researching Bose.

They raise serious questions about the confidentiality of Indian intelligence documents and the security establishment's doubts over Bose and his links with the Axis powers --Germany and Japan. Both nephews Amiya and Sisir, sons of Sarat Chandra Bose were on surveillance, according to the documents. Only 10,000 of the 70,000 pages of the voluminous records were made public three months earlier.

Other involved security and intelligence agencies

The Times of India Apr 12 2015

V Balachandran

IB played junior partner to MI5 well after 1947

We often think security and intelligence services are bestowed with greater intelligence than bureaucracy . Law rence J Peter of “Peter Principle“ said “Bureaucracy defends... status quo long past when quo has lost its status“. Security and intelligence establishments often follow this policy resulting in hilarious situations.Before 1947 IB was controlled by MI5, Britain's domestic intelligence service and a department called “Indian Political Intelligence“ (IPI), run by India Office, Scot land Yard and India government.

IPI, started by a lone Indian police officer in 1909 to keep vigil on revolutionaries, grew into a massive organization by World War II. By 1935, arrangements were made in all colonies integrating intelligence, police and security organizations to face freedom strug gles. From 1919, Britain considered the “Red Menace“ as their top challenge.

Our bureaucracy and IB continued that policy till 1975 when Indira Gandhi admonished them during the annual IB conference, which I attended.

After 1947 this MI5-IB liaison continued.An unwritten agreement during the transfer of power in 1947 was the secret positioning of a security liaison officer (SLO) tioning of a security liaison in New Delhi as MI5's representative. This was obtained by Guy Liddel, then deputy D-G, MI5, declassified archives say .

Normally , any intelligence liaison with an independent country should've been maintained by Britain's foreign intelligence service -MI6. But MI5 resisted such attempts till 1971. British archives quoted then IB director S P Verma writing to the MI5 chief that he didn't know “how he'd manage without a British SLO“, when told about his withdrawal.

IB followed Britain's intelligence priori ties. British archives reproduced a letter from the late T G Sanjeevi Pillai, IB's first director, on the need for liaison with MI5. Sanjeevi didn't like V K Krishna Menon, a Nehru confidante. The dislike was shared by Liddel who assured his government: “We're doing what we could to get rid of Krishna Menon“. They didn't succeed. B N Mullik, second director, continued this policy . According to British archives he “encouraged“ Walter Bell, then SLO, to visit IB's headquarters to see its work on preventing communist subversion.fied British archives speak of dis Declassified British archives speak of disconnect between Nehru's policies and IB's priorities. This was evident during the exchange visits of Soviet leaders Bulganin and Khrushchev to India and Nehru's USSR visit heralding closer Indo-Soviet ties in 1955. One year later there was a chill in Indo-UK ties when Nehru condemned the Anglo-American invasion on the Suez. This “had little impact“ on the IBMI5 collaboration. IB allowed MI5 to study its records on Moscow's subsidies to Indian communists. In 1957, Mullik wrote to Roger Hollis, MI5 chief: “...I never felt I was dealing with any organization which was not my own“.

Christopher Andrew, official MI5 historian, concludes: “Nehru either never discovered how close the relationship was or -less probably-did discover and took no action“.

This needs to be kept in mind before concluding Nehru ordered IB snooping on Netaji's family. Declassified IPI records indicate Bose was under watch since April 1924. In 1922 revolutionary Abani Mukherjee was sent by Comintern to India. Purabi Roy , Netaji's biographer says he spent 11 months in Calcutta.British intelligence must've started watch over Subhas and his family after this. A full picture will be available only if we declassify all our Bose records.

Surveillance by the Nehru government

The Times of India Apr 12 2015

FAMILY QUESTIONS - Was Nehru privy to a Netaji secret?

Subhro Niyogi

The extraordinary surveillance that Nehru's government mounted on Netaji's kin is akin to intelligence operations against suspected terrorists, shocked Bose family members told TOI in the wake of reports from two declassified files on Subhas Chandra Bose. The Nehru government's surveillance on Netaji's relatives is akin to intelligence operations against suspected terrorists, Bose family members say . “We knew we were being watched, but had no idea it was to this degree. The lengths to which intelligence operatives went to procure information --snooping on our mail, trailing family members--shows this was no ordinary surveillance. It reveals Nehru's anxiety about the Bose clan,“ said Chandra Bose, grandson of Netaji's brother Sarat. Of Netaji's six brothers and six sisters, he was closest to elder brother Sarat.

What the family finds difficult to explain is the motive behind the surveillance. Sarat Bose's daughter Chitra Ghosh says the initial years of spying, post-Independence, could've been a colonial legacy . “It was natural to be under watch during British rule. I don't believe it continued more than two decades without special instructions. It should've ceased after my father died in 1950. It didn't.“

Dwarakanath Bose, son of Netaji's brother Sunil, says Sarat's sons Amiya and Sisir weren't even politicians when surveillance was on. “ Amiya was a barrister and Sisir a pediatrician. Amiya joined politics in 1968 when he was elected MP , Sisir in the 1980s,“ he reasoned.

Was there a Bose secret that made Nehru wary? That appears logical, the family believes. Chitra is certain Nehru knew Netaji hadn't died in the crash but he might not have known where he had gone either. “It's perhaps this desperation to know where Netaji was and the insecurity playing on his mind that led to the surveillance,“ she said.

Sugata, son of Sisir Bose who drove the car from the Elgin Road house in the first leg of Netaji's Great Escape from house arrest in 1941, has another take. “Surveillance... intensified after 1957 when father began inviting former INA members to collect material for Netaji Research Bureau. Perhaps his actions were misconstrued and led Nehru to apprehend that he was preparing to mount a political challenge,“ said Sugata, Harvard professor and now Trinamool RS MP .

What family members find devious is Nehru's apparent friendliness with the family , particularly with Sarat and his son Amiya. Nehru stayed at 1 Woodburn Park during visits to Kolkata. “In 1949, we travelled to Europe to meet INA members...In Rome we met Quorini, Italian consul in Kabul at the time of the Great Escape.He had given Subhas an Italian passport in the name of Orlando Mazzotta. We met Netaji aides ACN Nambiar and NG Swamy . When we arrived in London, Nehru was there and he exclaimed, `What's Sarat doing here?'“ Chitra recounted.

MHA was reluctant to renew Amiya's passport before his Japan visit. “There was curiosity on why he was going to Japan, whether a trip to Renkoji where Netaji's alleged ashes are kept was on the itinerary ,“ says Chandra.

Efforts of Congress to shield Nehru

The Times of India Apr 12 2015

Himanshi Dhawan

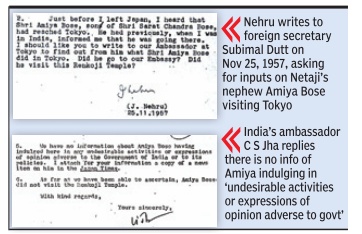

Sought info on Bose nephew's visit to Japan

The controversy over whether the Nehru government ordered surveillance on Netaji Subhas Chan dra Bose's family seems set to escalate following disclosure that the first PM had personally sought information on their whereabouts. Documents accessed by author Anuj Dhar for his book, `India's Biggest Coverup', show that Nehru, in a let ter dated November 25, 1957 to the then foreign secretary Subimal Dutt, sought to know what Bose's nephew Amiya Nath Bose was doing in Tokyo. In response, India's ambassador to Tokyo reported back assuring New Delhi that Amiya Bose had not “in dulged in any undesirable activities. Amiya Bose, son of Subhas's brother Sarat Chandra Bose, was known to be close to Netaji.

Dhar has researched Netaji Bose for the last 15 years and has accessed rare archival material from British and Indian national archives for his book.

The revelation deals a setback to Congress's effort to buffer Nehru against the snooping charge that the Intelligence Bureau reported directly to the home minister. Documents showing that Jawaharlal Nehru had sought information on Netaji Subhas Bose's nephew Amiya Nath Bose's activities in Japan deals a setback to Congress's effort to shield the first PM from charges of snooping by claiming that the Intelligence Bureau reported directly to the home minister.

Congress spokesperson Abhishek Singhvi on Friday had alleged that the allegation that Nehru had spied on Bose's family for 20 years between 1948 to 1968 was a “systematic and sinister propaganda of selective leaks and half-truths in an attempt to tarnish the image of national icons and former home ministers like Vallabhbhai Patel, C Rajagopalachari, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Govind Ballabh Pant, Gulzarilal Nanda and others. The party has held that the IB reports to the home ministry seeking to contain the damage that the snooping was directed by Nehru himself.

“Just before I left for Japan, I heard that Shri Amiya Bose, son of Shri Sarat Chandra Bose, had reached Tokyo.He had previously , when I was in India, informed me that he was going there. I should like you to write to our Ambassador at Tokyo to find out from him what Shri Amiya Bose did in Tokyo. Did he go to our Embassy? Did he visit this Renkoji Temple? said Nehru's note to foreign secretary Dutt in November of 1957.

In response, then ambassador in Tokyo C S Jha wrote, “We have no information about Amiya Bose having indulged in any undesirable activities or expressions of opinion adverse to the Government of India or to its policies. I attach a copy of a news item on him in the Japan Times. As far as we have been able to ascertain, Amiya Bose did not visit Renkoji Temple.

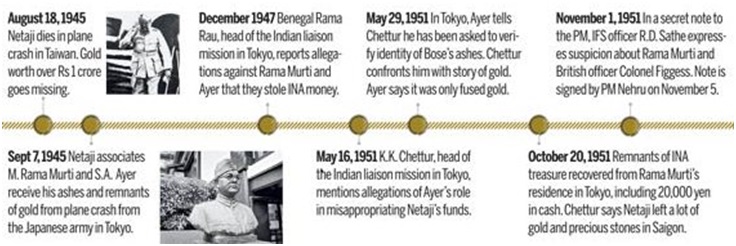

'INA Treasure'

Sources: India Today:

1. India Today

2. India Today

Sandeep Unnithan

May 15, 2015

Netaji files reveal Jawaharlal Nehru government knew of Subhas Chandra Bose's missing treasure chest

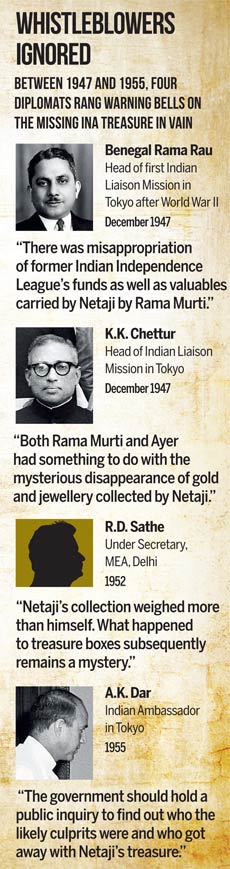

Locked away in the vaults of South Block and protected by the Official Secrets Act for over half a century, are revelations of one of India's earliest scandals. Hundreds of yellowing documents that raise serious suspicions about cash, gold and jewellery that Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose collected to finance his armed struggle for Independence being siphoned away.

One of the 37 secret 'Netaji files' in the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) and Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) deals with the 'INA Treasure'. Built over the years with secret reports, letters and frantic telegrams, it deals with a story of suspected rank greed and opportunism which overcame Indian freedom fighters as they looted the treasury of the collapsed Provisional Government of Azad Hind (PGAH). This suspected loot took place soon after Bose's demise in a plane crash in 1945. But the startling twist is not about the missing Indian National Army (INA) treasure worth several hundred crores of rupees today. It is that the government of the day knew about it but did nothing. Classified papers obtained by INDIA TODAY reveal that the Nehru government ignored repeated warnings from three mission heads in Tokyo between 1947 and 1953. R.D. Sathe, an under secretary (later foreign secretary) in the MEA, wrote a stark warning to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, also the foreign minister, in 1951 that a bulk of the treasure - gold ornaments and precious stones - had been left behind by Bose in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), Vietnam. This treasure, Sathe concluded, had already been disposed of by the suspected conspirators.

All these warnings were ignored. No inquiry was ordered. Worse, one of the former INA men these diplomats suspected of embezzlement was rewarded with a government sinecure.

On April 13, Surya Kumar Bose , Netaji's grandnephew met Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Berlin just three days after an India Today expose revealed this snooping. The family's outrage has now given way to a resolute demand for declassification of over 150 'Netaji files' still held by the government. On May 9, the Prime Minister assured Bose family members of declassification. "Don't call it a people's demand, it is the nation's duty," Modi told family members in Kolkata. But as these extraordinary revelations, some of them mentioned in author Anuj Dhar's 2012 book, India's Biggest Cover-Up, show the government has had much to hide.

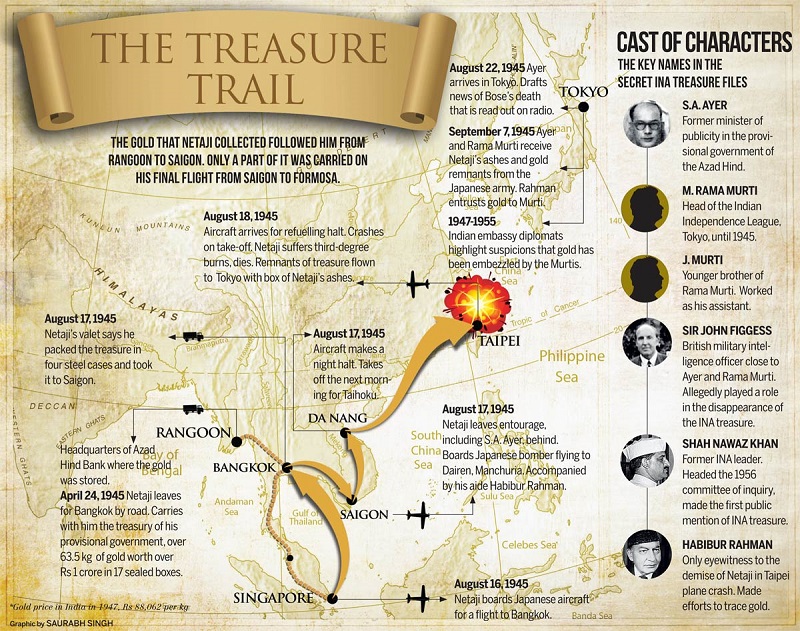

On January 29, 1945, Indian residents of Rangoon, the capital of Japaneseoccupied-Burma, held a grand weeklong ceremony. It was the 48th birthday of Netaji, the head of the provisional government of the Azad Hind. It was a birthday quite unlike any other.

Netaji, the iron patriot who coined the slogan "Jai Hind" and exhorted his troops to march to Delhi, was weighted against gold, "somewhat to his distaste", Hugh Toye notes in his biography The Springing Tiger: The Indian National Army and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. Over Rs 2 crore worth of donations were collected that week including more than 80 kg of gold.

Fund collection drives were not new to the INA. Netaji wanted his two-year-old government-in-exile to depend as little on the Japanese for financing his soldiers. He turned to an estimated two million Indians in erstwhile British colonies conquered by his Japanese allies.

He relied on the sheer dint of his personality, emotive speeches and unswerving commitment to Indian independence to ask the community for funds. "After he spoke," writes Madhusree Mukherjee in her 2010 book Churchill's Secret War, "housewives would come up and strip their arms and necks of gold to serve the cause of freedom". At one such impassioned fund-raising public meeting in Rangoon on August 21, 1944, newspapers of the day recalled, Hiraben Betani gave away 13 of her gold necklaces worth Rs 1.5 lakh and Habib Sahib, a multi-millionaire, gifted away all his property worth over Rs 1 crore to the Netaji Fund. Another INA funder, Rangoon-based businessman V.K. Chelliah Nadar, deposited Rs 42 crore and 2,800 gold coins in the Azad Hind Bank.

Netaji had raised the largest war chest by any Indian leader in the 20th century. But by 1945, this was to no avail as the Japanese army and the INA crumpled in the face of a resurgent Allied thrust into Burma. It was only a matter of time before Rangoon, headquarters of the Azad Hind Bank and the springboard for the leap into India, fell to the Allies. Netaji retreated to Bangkok on April 24, 1945, carrying with him the treasury of the provisional government. There are conflicting accounts on how much gold he took.

Dinanath, chairman of the Azad Hind Bank interrogated by British intelligence soon after the war, said Netaji left with 63.5 kg of gold. Debnath Das, head of the Indian Independence League (IIL) in Bangkok, told the Shah Nawaz Committee of inquiry in 1956 that Netaji withdrew treasure worth Rs 1 crore, mostly ornaments and gold bars in 17 small sealed boxes. General Jagannath Rao Bhonsle of the INA also told the Committee that Netaji brought gold ornaments and cash packed in six steel boxes.

On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers. The 40,000-strong INA also surrendered to the Allied forces in Burma, their officers marched off to the Red Fort to face trial for treason.

A terrible fate awaited the first Indian in nearly a century to lead an insurrection against the British empire. Netaji had been marked for assassination by Winston Churchill in 1941 and in 1945, had told his aides he would be "lined up against a brick wall and shot" if captured. On August 18, Netaji, along with his aide Habibur Rahman, boarded a Japanese bomber in Saigon bound for Manchuria, where he would attempt to enter the Soviet Union.

Habibur Rahman recounted the last hours of Netaji before the Shah Nawaz Committee in 1956. Netaji had been injured in the plane crash but his uniform, soaked in aviation fuel, caught fire, grievously injuring him. He died in a Japanese army hospital six hours after the air crash.

Also destroyed in the aircraft were two leather attaches, each 18 inches long, packed with INA gold. Japanese armymen posted at the airbase gathered around 11 kg of the remnants of the treasure, sealed them in a petrol can and transported it to the Imperial Japanese Army headquarters in Tokyo. A second box held the remains of Netaji's body that had been cremated in a local crematorium in Taiwan.

The two containers came to represent two of modern India's biggest political mysteries: the fate of Netaji and the whereabouts of his treasure. Where was the rest of Netaji's war chest? It beggared belief that over 63.5 kg of treasure could have turned into a 11 kg lump of charred jewellery.

Exact numbers were hard to come by in the melee of defeat. The INA and the Japanese destroyed documents to prevent them falling into Allied hands, further confusing the picture. Inquiry commissions relied on eyewitness accounts to build a picture of the INA treasure.

An 18-page secret note, prepared for the Morarji Desai government in 1978, quotes Netaji's personal valet Kundan Singh as saying that the treasure was in "four steel cases which contained articles of jewellery commonly worn by Indian women, chains of ladies watches, necklaces, bangles, bracelets, earrings, pounds and guineas and some gold wires". It also included a gold cigarette case gifted to him by Adolf Hitler. These boxes were checked before Netaji departed from Bangkok to Saigon. A leader of the IIL in Bangkok, Pandit Raghunath Sharma, said that Netaji took with him gold and valuables worth over Rs 1 crore. There was clearly much more of the treasure than the two leather suitcases burnt in the airplane crash. One man who knew this was S.A. Ayer, a former journalist-turned-publicity minister in the Azad Hind government.

Ayer was with Netaji during his last few days. On August 22, 1945, he flew from Saigon to Tokyo and joined M. Rama Murti, former president of the IIL in Tokyo, to receive two boxes from the Japanese army. They deposited Netaji's ashes with the Renkoji temple in Tokyo. Murti kept the treasure. On August 25, 1946, Lt-Colonel John Figgess, a military counterintelligence officer posted in the headquarters of the Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia, submitted a report to his superior Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Figgess, whose 1997 obituary credited him with "the successful emasculation of the pro-Japanese Indian National Army formed and led by Subhas Chandra Bose", concluded that Netaji had indeed died in the plane crash in Formosa (now Taiwan).

The warnings from Tokyo

On December 4, 1947, Sir Benegal Rama Rau, the first head of the Indian liaison mission in Tokyo, made a startling allegation. In a letter written to the MEA, Rau alleged that Murti had embezzled IIL funds and misappropriated the valuables carried by Netaji. The ambassador's letter was prompted by complaints from local Indians. Japanese media at the time reported how Rama Murti and his younger brother J. Murti lived in affluence and rode in two sedans, an unusual sight in war-ravaged Japan. The formal reply that the president of the Indian Association in Tokyo got from the mission was that the Indian government could not interest itself in the INA funds. The government became interested in the INA treasure only four years later, in May 1951, when an exceptionally persistent diplomat, K.K. Chettur, headed the Indian liaison mission in Tokyo-India was yet to establish full-fledged diplomatic relations with Japan.

Chettur noted with dismay the return of Ayer. He was now a director of publicity with the government of Bombay state. Now, seven years later, Ayer was going back to Tokyo on what he claimed was a holiday but actually with a secret agenda. In a series of back-and-forth cables to the foreign office in New Delhi, Chettur also made the first mention of a phrase "INA treasure". From then on, this phrase stuck in government use.

Ayer told Chettur in Tokyo that he had been entrusted twin tasks by the government of India: to verify whether the ashes kept in the Renkoji temple were those of Netaji and to retrieve the gold jewellery that had been recovered from the crashed aircraft. In a secret dispatch to the MEA, Chettur said that local Indians were "seething with anger at the return of Ayer and his association with these two brothers (the Murtis)" as "both Rama Murti and Ayer had something to do with the mysterious disappearance of the gold and jewellery collected by Netaji".

But Ayer had already pulled a rabbit out of his hat. He informed Chettur that part of the INA treasure had survived and had been in Rama Murti's custody since 1945. In October 1951, the Indian embassy collected the remnants of the INA treasure from Rama Murti's residence. Ambassador Chettur still disbelieved the Ayer-Rama Murti story. In a cable to New Delhi he relayed his apprehensions. Chettur believed that Ayer, apprehensive of an early conclusion of the Peace Treaty in 1945, had come to Tokyo to "divide the loot" and draw a red herring across the trail by handing over a small quantity of gold to the government.

In one of his final communications to New Delhi on June 22, 1951, Chettur offered to probe the disappearance of the "Netaji collections". The first comprehensive warning of foul play in the INA treasure followed just months later. It was a two-page secret note authored by R.D. Sathe on November 1, 1951. "INA Treasures and their handling by Messrs Iyer and Ramamurthi" summed up the story: considerable quantities of gold and treasures were given to the late Subhas Chandra Bose by Indians in the Far East as part of their war effort; all that was left of it was 11 kg of gold and 3 kg of gold mixed with molten iron and 300 grams of gold brought by Ayer from Saigon to Tokyo in 1945. Rama Murti had been questioned several times by Indian officials but had denied the existence of the treasure. Ayer's activities in Japan were suspicious, Sathe said. "What is still more important is that the bulk of the treasure was left in Saigon and it is significant from information that is available that on the 26th January, 1945, Netaji's collection weighed more than himself." Sathe pointed at Ayer's movements from Saigon to Tokyo, an eyewitness who claimed to have seen the boxes in his room. "What happened to these boxes subsequently is a mystery as all that we have got from Ayer is 300 gram of gold and about 260 rupees." Sathe also flagged a relationship that had baffled most Indians in Japan.

Rama Murti's proximity to British intelligence officer Lt-Col Figgess. He was now posted as a British liaison officer at General Douglas MacArthur's occupation headquarters in Tokyo. What was the glue that held Colonel Figgess and his erstwhile INA foes together? Sathe's letter has one conjecture. "Suspicion regarding the improper disposal of the treasure is thickened by the comparative affluence in 1946 of Mr Ramamurthy when all other Indian nationals in Tokyo were suffering the greatest hardships. Another fact which suggests that the treasures were improperly disposed of is the sudden blossoming out into an Oriental curio expert of Col Figgess, the Military Attaché of the British Mission in Tokyo and the reported invitation extended by the Colonel to Ramamurthy to settle down in UK."

This note was signed by Jawaharlal Nehru on November 5, 1951. "PM has seen this note. This may be placed on the relevant file," then foreign secretary Subimal Dutt signed off on it. Prime Minister Nehru's thoughts that year were clearly about the first Indian General Election that began in October that year. The Congress was set to sweep the elections. There was no charismatic opposition leader. The fate of Subhas Chandra Bose was still unclear. Rumours suggested he could still be alive, ready to return to India as a possible challenger only fuelled the government's doubt-one of the probable reasons the Intelligence Bureau had the family members under surveillance.

Conclusive evidence that Netaji had died in the air crash could help silence government critics. This evidence came from Ayer. On September 26, 1951, Nehru wrote to Foreign Secretary Dutt that Ayer had met him with an inquiry report. Ayer, Nehru wrote, "was dead sure that there was no doubt at all about Shri Subhas Chandra Bose's death on the occasion".

It now turns out that Chettur's suspicions were correct. Ayer was on a covert mission for the government. In 1952, Prime Minister Nehru quoted from Ayer's report in Parliament affirming that Netaji had indeed died in an air crash in Taipei. The INA treasure, or what was left of it, was secretly brought into India from Japan. It was inspected by Nehru who called it a "poor show". There was a debate within his cabinet on what to do with it. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the education minister, suggested the gold be given to Netaji's family. Nehru overruled the suggestion. The Bose family had not accepted Netaji's death in an air crash, he said. Besides, the burnt jewellery should be preserved by the government since it was some evidence of the aircraft accident and subsequent fire. The jewellery was sealed and consigned to the vaults of the National Museum, then located in the Rashtrapati Bhavan .

The following year, Ayer was appointed adviser, integrated publicity programme, for Nehru's Five Year Plan. The case was closed. Or was it? The warnings from the Indian mission in Japan continued to pour in. In 1955, A.K. Dar, the ambassador in Tokyo, made another explosive accusation. In a four-page secret note sent to South Block, Dar again demanded a public inquiry which if it would not get back the treasure would at least determine who the likely culprits were and who did away with it.

Dar mentioned the "disinterested attitude of the Government of India for almost 10 years" because "it not only helped the guilty parties concerned to escape without blame but also because it postpones the rendering of honour to one of the great leaders who gave his life for the independence of the country".

More warnings but no action

The INA Treasure papers throw up more questions than answers. A retired diplomat who studied the papers is unable to understand why the government did not order an inquiry. "If we had suspicions that the treasure was looted, the government should have leaned on the Allied Powers then running Japan to order an inquiry," he says.

PM Nehru was in the loop on most INA matters and was quick to intervene in other cases where former INA men sought to cash in on their wartime fortune. In a November 1952 letter signed by B.N. Kaul, principal private secretary to the PM, Nehru directed the Central Board of Revenue not to refund Rs 28 lakh recovered from five INA special forces men who had landed on the Orissa coast in a Japanese submarine in 1944. They were arrested by the British and the money, meant for subversive operations in India, confiscated from them. Nehru's silence on the fate of the INA treasure is baffling, especially since the Shah Nawaz Committee set up by him to probe Netaji's disappearance in 1956 also recommended an inquiry into the fate of it. It was impossible to conclude what had happened to the treasure, the committee noted and called an inquiry into all the assets of Netaji's government.

Two prominent Indians based in Japan who deposed before the one-man inquiry commission headed by Justice G.D. Khosla in 1971 also claimed the treasure had been embezzled. They told Justice Khosla about the sudden affluence of the Murtis in Japan. One of the witnesses, veteran Tokyo-based journalist K.V. Narain, asserted that Ayer had come to Japan with two suitcases of jewellery which he gave Rama Murti in 1945. In its report of June 30, 1974, the Khosla commission noted that part of the treasure had been misappropriated by Ram Murti and his brother J. Murti. But the commission could not find proof and felt the quest would not yield anything.

That the revelations within the 'INA Treasure' file is a ticking time bomb has been known to the government. In 2006, the government declassified one INA treasure file from the sensitive 'Not To Go Out' section of the PMO. File 23(11)/56-57 now placed in the National Archives is, however, scrubbed of any references to the angry reports from diplomats Chettur, Sathe and Dar. The file only speaks of the 11 kg of gold that survived the air crash, now in the National Museum.

"The loot of the INA treasure is free India's first scam, it predates the 1948 jeep scandal by one year. Its implications are far more horrendous as details on record suggest some sort of complicity on the part of Jawaharlal Nehru," alleges Anuj Dhar.

S.A. Ayer's Mumbai-based son Brigadier A. Thyagarajan (retired) rubbishes the speculation that his father had anything to do with the embezzlement of the INA treasure. My father came back to Mumbai after his fact-finding mission and started from scratch," he told india today. "He had no treasure. He had a large family of seven children to look after. When he died in 1980, he had a small bank balance with savings from his pension, he didn't own any property and lived in a rented apartment till his demise."

Netaji's grand-nephew and Trinamool Congress MP Sugata Bose says he is aware of Rama Murti being treated with suspicion by the Shah Nawaz Committee but dismisses reports linking Ayer to the missing treasure as "speculative". "I would be careful about making charges about anyone without credible evidence," he says.

J. Murti's son Anand J. Murti, who runs a chain of restaurants in Tokyo, is baffled by the allegations in the files. "What I remember being told is that when Netaji's cremated ashes and his molten luggage were brought to Tokyo by the Japanese military and received by Rama, he handed the luggage to Ayer and (Habibur) Rahman and took the ashes to a Buddhist temple in hiding from the Allied occupation forces."

That part of the INA treasure had been secretly transferred to Delhi in a secret operation was revealed only in the 1970s. In 1978, Subramanian Swamy, then a Janata Party MP, made a sensational public claim that the INA treasure had been embezzled by Prime Minister Nehru. In a letter written to Prime Minister Morarji Desai, he demanded an inquiry into the disappearance of the treasure and its covert transfer to India. Desai made a statement in Parliament later that year that part of the treasure had indeed been transferred to India. A secret report submitted to Desai's PMO by the MEA summed up all the facts of the case, beginning from Netaji's final journey to the arrival of part of the treasure to India. It included the role of Chettur, the whistleblower in the case, and the questionable conduct of Ayer and Rama Murti. The Morarji Desai government, however, did not order an inquiry. The INA treasure case was quickly forgotten. None of the key players are alive today, although some of their descendants still nurse the hope of reclaiming the fortune.

One of the last claimants to the INA treasure died in 2012. Ramalinga Nadar, the son of Rangoon-based businessman V.K. Chelliah Nadar, had petitioned the government for the Rs 42 crore and 2,800 gold coins which his father had deposited in the Azad Hind Bank in Rangoon in 1944. "In 2011, RBI officials told the Nadars they had nothing to do with the INA treasure and treated the matter as closed," says his son-in-law KKP Kamaraj.

Prime Minister Modi's promise of declassification has breathed life into an issue buried by successive governments. "Declassification of all government files is a must to dispel all the theories about Subhas Chandra Bose and clear mysteries like the disappearance of the INA Treasure," Netaji's grand-nephew and Bose family spokesperson Chandra Bose told India Today. The question remains as it has for over half a century- whether the government can handle the truth.

Treasure trove of secrets

Netaji was a somewhat late entrant into India's pantheon of freedom fighters. His portrait was unveiled in Parliament in 1978, possibly because it marred the Gandhian narrative of a non-violent freedom struggle. Over 2,000 INA soldiers who died fighting the British in Burma and the North-east were also sidestepped by history books. Over the years, the Bose legend has not only attracted admirers such as the LTTE's late chief Velupillai Prabhakaran but also a deluge of conspiracy theories. Bose was believed to have escaped to China and the Soviet Union, later returning to India where he lived as a 'baba' in Faizabad, UP, until his death in 1985. These theories were founded in his real-life escapades: Bose disguised as a Pathan to escape into Afghanistan, an Italian businessman to travel through Russia and finally hopped from a German submarine to a Japanese submarine in the Indian Ocean. The theories would have fizzled out but for the government's refusal to declassify the Netaji files.

"The fact that the files have not been declassified, when they should have been in the 1960s and 1970s, has only added to the Bose mystery," says Wajahat Habibullah. During his five-year stint as India's first chief information commissioner, Habibullah handled multiple requests for declassification of the Netaji files, all of which were turned down by the government.

Every government since Nehru's has told politicians, researchers and journalists that the contents of over 150 secret 'Netaji Files' are so sen- sitive that their revelations would create law and order problems, especially in West Bengal. Worse, they would "spoil India's relations with friendly foreign nations". The Modi government in 2014 deleted the law and order fallout of the revelations but maintained the official line. Responding to a query from Trinamool Congress MP Sukhendu Sekhar Roy, Minister of State for Home Affairs Haribhai Parthibhai Chaudhary said, in a written reply in the Rajya Sabha on December 17, 2014, declassification was "not desirable from the point of view of India's relations with other countries". Five Netaji files locked in the PMO are so secret that even their names have not been disclosed under the Right to Information Act.

What terrible state secrets sit in those files locked in the PMO? Secrets, which in the words of Roy, made Rajnath Singh go from an espouser of the truth to someone who "sat in the Lok Sabha, silently nodding his head while I asked for declassification".

"How can Netaji's death in an air crash be blamed on foreign countries?" Roy asks. "There are clearly some other reasons which both the BJP and Congress want to cover up."

Two of them, the Shah Nawaz Committee in 1956 and the Khosla Commission in 1974 said Netaji died in a plane crash. Their findings were rejected by then Prime Minister Morarji Desai in 1978. The Justice (M.K.) Mukherjee Commission's suggestion that Netaji had faked his death and had escaped to the Soviet Union was rejected by the UPA government in 2006.

Often, the inquiries have fuelled speculation. BJP leader Subramanian Swamy picks out the testimony of Shyam Lal Jain, Nehru's stenographer who deposed before the Khosla Commission in 1970. Jain swore he had typed out a letter which Nehru then sent to Stalin in 1945 in which he admitted knowing of Bose's captivity.

"The plane crash was a ruse. Netaji sought asylum in the Soviet Union where he was imprisoned and later killed by Stalin," Swamy claims. Bose family members, including Anita Bose-Pfaff, want reports lying with the Centre and state governments to be declassified. "A special investigative team with representatives from the PMO, foreign ministry, IB, CBI and historians need to research those papers and reveal to the public the story of Subhas Bose," says Chandra Kumar Bose. If the current revelations are anything to go by, the Netaji files could bring the curtains down on India's longest running political mystery.

Family under surveillance

Nehru govt spied on Subhash Chandra Bose's family for 20 years: Report

The Times of India TNN | Apr 10, 2015

NEW DELHI: The Jawaharlal Nehru government had placed the family and relatives of Subhas Chandra Bose on surveillance for two decades, Times Now reported quoting de-classified intelligence reports.

Reacting to reports, the family of Subhas Chandra Bose sought full declassification of files that revealed that the Nerhu government had placed Bose family under surveillance.

However, taking the line adopted by the previous Congress-led UPA government, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Office has already refused to disclose records related to Subhas Chandra Bose's death as it rejected the argument that there was a larger public interest involved in making them public.

Why snoop on the family?

"Nobody has done more harm to me, than Jawaharlal Nehru," wrote Netaji in 1939, in a letter to his nephew Amiya Nath Bose. The two claimants to Mahatma Gandhi's political legacy split when he chose Nehru over Subhas Bose as his political successor because he was uncomfortable with the latter's push for complete independence. Meanwhile, Nehru was uncomfortable with Bose's admiration for Nazi Germany and Facist Italy. Finally, Netaji resigned as Congress president in 1939. Historian Rudrangshu Mukherjee's 2014 book Nehru & Bose: Parallel Lives states that "Bose believed he and Jawaharlal could make history. But Jawaharlal could not see his destiny without Gandhi, and the latter had no room for Subhas".

Netaji however bore Nehru, eight years his senior, no ill will. He considered him an older brother and even named one of the INA regiments after him. Nehru publicly wept when he learned of Subhas Bose's death in 1945.