Pathalgarhi movement

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> Additional information ma...") |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

=The movement= | =The movement= | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

Sensing the mood, the Congress, in its election manifesto, had promised to protect ‘jal, jungle and jameen’ of tribal communities. After coming to power, the Congress government returned the land acquired from tribals in Bastar to its original owners after Tata Steel’s integrated steel plant project — for which the land was acquired — failed to come up. | Sensing the mood, the Congress, in its election manifesto, had promised to protect ‘jal, jungle and jameen’ of tribal communities. After coming to power, the Congress government returned the land acquired from tribals in Bastar to its original owners after Tata Steel’s integrated steel plant project — for which the land was acquired — failed to come up. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Politics= | ||

| + | ==As in 2019, April== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2019%2F05%2F04&entity=Ar01913&sk=5E5391A7&mode=text Jaideep Deogharia & Chandrima Banerjee, May 4, 2019: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Why Jharkhand’s Pathalgarhi villages plan to vote in fight for autonomy | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tribal Resistance Changes Tack After Crackdown | ||

| + | |||

| + | Khunti: | ||

| + | |||

| + | The undulating roads of Khunti are dotted with huge stone slabs, painted green with white text, claiming the tribal communities’ right to self-rule. The Pathalgarhis (stone plaques) have been in place for two years, delegitimising the rule of any elected government over tribal land. But now, before Khunti votes in the Lok Sabha elections on May 6, the movement has changed tenor, and strategy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Older Pathalgarhis, set up in 2017, have switched from Hindi to Mundari, asserting in even stronger terms the tribals’ claim to autonomy. These go back to older precedents, referring to the Chotanagpur Tenancy Act and Mundari Khuntkatti (a lineage-based system of collective landholding by tribal communities). Pathalgarhis erected in 2018 have stuck to Hindi, declaring “India Non Judicial” and dismissing voter cards and Aadhaar cards as “anti-Adivasi” documents. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At Laterjang, which set up its Pathalgarhi in 2017, freshly painted wall graffiti repeats these statements — “Lok Sabha na Vidhan Sabha, sab se ooncha Gram Sabha (not Lok Sabha or assembly, gram sabha is the highest authority)” — but other messages make the political climate clear. One sarcastic take says, “Adivasi log gehri neend mein soye huye the. Raghubar Das aur Narendra Modi ne milkar Momentum Jharkhand laaya to yahaan paanchvi anusuchi ka bhoot nikal gaya. Bahut achchha kiya Raghubar Modi ne isliye CM ko bahut bahut dhanyavaad (Adivasis were in deep slumber. CM Raghubar Das and PM Modi together brought investors’ summit Momentum Jharkhand and destroyed the spirit of the Fifth Schedule. We thank the CM),” says another. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the next lane, as Congress workers distribute NYAY enrolment forms and put up party flags, there is no resistance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Just like Laterjang, Kochang — a stronghold of the Pathalgarhi movement — has decided to participate in the elections. A year ago, Kochang shot to the headlines after an alleged gang-rape in which Pathalgarhi supporters were implicated. Several arrests followed, including that of a cardinal at the Burudih church. While the government accused the movement of fostering criminal elements, Pathalgarhi supporters saw it as a conspiracy against them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A week ago, a Congress party office was set up opposite the Pathalgarhi. “Everyone here will vote, just to replace the present government. Under Pathalgarhi, we do not believe in elections, but the kind of repression we faced forced us to change our strategy,” says Kali Munda, a Pathalgarhi leader at Kochang. “The government has tried to take away the rights of indigenous people across the country. It has tried to divide Christians and Sarnas (followers of animism), but we don’t believe we’re different.” | ||

| + | Beyond Kochang, the villages of Sakey and Saali are still holding their ground against elections, as is Udburu, the first Pathalgarhi village to set up its own banking system. Just like Kochang, Udburu saw a massive crackdown on its leaders last year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Areas around arterial roads, like Chitramu or Burudih, have either pulled down the Pathalgarhi or painted over it. Chitramu pulled down its plaque last year, with a ceremony marked by funerary rituals. “Government officials told us we will get access to development schemes if the Pathalgarhi is removed,” says Kishun Swasi, a village elder. Others simply don’t want any more trouble. “We will vote and see if anything changes for us,” says a villager at Alhaudi, where the Pathalgarhi still stands at the village square and has been painted over, but not enough to render the text illegible. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:India|P | ||

| + | PATHALGARHI MOVEMENT]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|PATHALGARHI MOVEMENT]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Politics|P | ||

| + | PATHALGARHI MOVEMENT]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:10, 17 November 2020

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] The movement

[edit] As in 2019

From: Jaideep Deogharia and Chandrima Banerjee, (With reports from Mihir Ray in Rourkela and Joseph John in Raipur), January 25, 2019: The Times of India

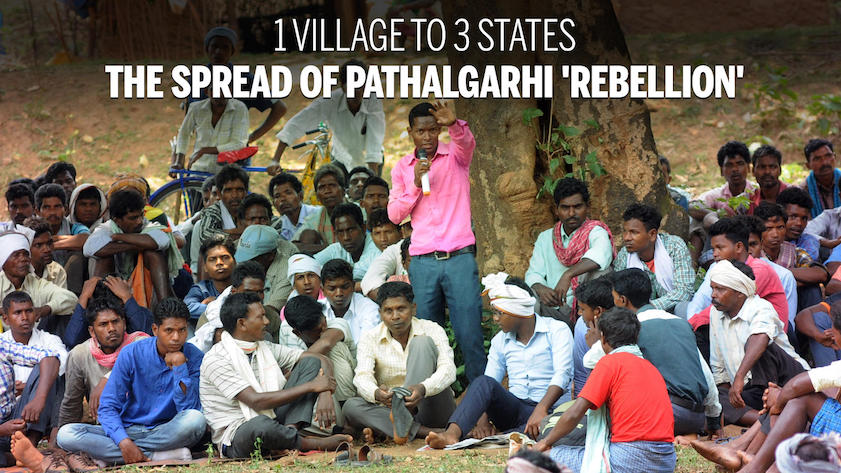

The signs of change are hard to miss the moment one enters Jharkhand’s Khunti district, birthplace of two tribal rebellions separated by a century. “ Sab se upar gram sabha (gram sabha above all else),” announces the writing on a wall. It all started on March 9, 2017, when Bhandra village in the tribal-dominated district inaugurated its ‘pathalgarhi’, a huge stone slab announcing the autonomy of the village from all forms of government control. The Pathalgarhi movement that erupted from this is still going strong, having spread and made impact in neighbouring Odisha and Chhattisgarh.

“Pathalgarhi will not stop. The government has to recognize the legitimacy of what we are asserting. No effort to quell the movement with subversive tactics will deter us,” says Marcus Purti (name changed) from Torakera village, Jharkhand, associated with the movement.

What the villages are asserting is the right of the people to administer areas where they live, based on an interpretation of constitutional provisions like the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 or PESA Act and the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution. Pathalgarhi has been inspired by two systems — the traditional system of ‘sasandiri’, or stone slabs with which Munda tribespeople mark the spot where ashes of the dead are buried, and an awareness drive launched by IAS officer BD Sharma, commissioner of Bastar and champion of tribal rights, and IPS officer-turned-politician Bandi Oraon to empower tribals by spreading the word about PESA provisions.

Demarcating every Pathalgarhi village is one such megalith. Meetings go on for days to arrive at a consensus on what each Pathalgarhi should say. Inaugurations of the slabs are grand affairs. In the initial days of the movement, the villages would send out invitations even to the President, Prime Minister, governor and chief minister.

A few men linger around the point of entry to each village, carrying axes just out of sight. Gram sabhas, governing councils for villages in areas administered under the Fifth Schedule are the final word in areas that have adopted Pathalgarhi, rejecting government intervention. Archers guard gram sabha meetings.

While traditional gram sabhas did not admit women, the movement in its present form makes no such discrimination. Government schools have been shut down and children study a curriculum different from what prevails in the rest of Jharkhand. Village heads have declared ownership of all natural resources in their areas, including water.

“Pathalgarhi is very much constitutional. We are asserting the rights of traditional gram sabhas under the provisions of the Fifth Schedule,” says Siddhesh Munda (name changed), acting pradhan of the gram sabha in Jikilita village in Khunti district.

From: Jaideep Deogharia and Chandrima Banerjee, (With reports from Mihir Ray in Rourkela and Joseph John in Raipur), January 25, 2019: The Times of India

Government response to the movement has gone from being dismissive to repressive. Opposition party Jharkhand Mukti Morcha has claimed the government has lodged cases against 1,500-odd people involved with Pathalgarhi. The government says only 23 cases have been filed against 250 people.

In June 2018, the gang-rape of five women from an NGO at Kochang, a nodal point of the movement, and the detention of four jawans who were in charge of BJP MP Karia Munda’s security at Ghaghra village brought the movement into the spotlight again.

Chief minister Raghubar Das, Jharkhand’s first non-tribal elected head, calls Pathalgarhi an illegitimate campaign aimed at giving “protective cover” to Maoists. The other spectre the government claims to be behind the movement is the Church. “Christian missionaries are making villagers restrict police from entering their areas so that they can cultivate poppy,” Das said. “We want such elements to mend their ways immediately. If they don’t pay heed, we will crush them,” he added.

In the past year, the movement also spread beyond the state to neighbouring Odisha’s Sundargarh district. Stone slabs were raised at the entrance to some villages in Sundargarh but the demand for tribal ‘self-rule’ here saw more instances of social groups facing off against the district administration over the interpretation and implementation of PESA. The slabs still stand but no new ones have been reported in the past few months.

“It is unfortunate that the state government is not serious about implementing PESA in a scheduled district like Sundargarh. Hence locals adopted Pathalgarhi, an age-old practice of creating awareness,” said Ramesh Minz, a native of Kutra block of the district.

In the recent past, PESA first made headlines in the district when the state government notified the formation of the Rourkela Municipal Corporation in 2014. Tribal rights organisations such as Sundargarh Zilla Adivasi Mulvasi Bachao Manch objected to the inclusion of several hamlets around the city in the proposed corporation area as, according to it, this went against the very spirit of PESA.

From: Jaideep Deogharia and Chandrima Banerjee, (With reports from Mihir Ray in Rourkela and Joseph John in Raipur), January 25, 2019: The Times of India

The anger over the corporation and what many claimed were CM Naveen Patnaik’s “anti-tribal” policies grew in intensity in the rural pockets of Sundargarh. Many local tribal leaders like Biramitrapur MLA George Tirkey and displaced tribals’ leader Baghe Lakra joined the call for decentralisation of power, close reading of the Constitution and implementation of PESA.

“Sundargarh is a scheduled district. We have been demanding the implementation of PESA here and therefore Pathalgarhi had some resonance in the district,” said Tirkey.

Meanwhile, in Chhattisgarh, the movement has quietened down, largely because a lot of the demands of the tribals have since been met. Between April and July, tribals from villages bordering Jharkhand had installed stone slabs.

From: Jaideep Deogharia and Chandrima Banerjee, (With reports from Mihir Ray in Rourkela and Joseph John in Raipur), January 25, 2019: The Times of India

While the movement in the state was peaceful, the then BJP government felt nervous as assembly elections were around the corner and alleged the movement was aimed at declaring these villages as “autonomous republics”.

A group of BJP workers took out a ‘Sadbhavana rally’ in the last week of April 2018 to these villages, where they damaged the stone slabs, leading to stone pelting. Besides, the then ruling party leaders also alleged that the Church was behind the movement, a charge strongly denied by the Christian community.

Chhattisgarh Sarva Adivasi Samaj patron and veteran tribal leader Arvind Netam said the state government never took PESA laws seriously and did not conduct gram sabhas under PESA whenever land acquisition took place for industrial and other projects.

Sensing the mood, the Congress, in its election manifesto, had promised to protect ‘jal, jungle and jameen’ of tribal communities. After coming to power, the Congress government returned the land acquired from tribals in Bastar to its original owners after Tata Steel’s integrated steel plant project — for which the land was acquired — failed to come up.

[edit] Politics

[edit] As in 2019, April

Jaideep Deogharia & Chandrima Banerjee, May 4, 2019: The Times of India

Why Jharkhand’s Pathalgarhi villages plan to vote in fight for autonomy

Tribal Resistance Changes Tack After Crackdown

Khunti:

The undulating roads of Khunti are dotted with huge stone slabs, painted green with white text, claiming the tribal communities’ right to self-rule. The Pathalgarhis (stone plaques) have been in place for two years, delegitimising the rule of any elected government over tribal land. But now, before Khunti votes in the Lok Sabha elections on May 6, the movement has changed tenor, and strategy.

Older Pathalgarhis, set up in 2017, have switched from Hindi to Mundari, asserting in even stronger terms the tribals’ claim to autonomy. These go back to older precedents, referring to the Chotanagpur Tenancy Act and Mundari Khuntkatti (a lineage-based system of collective landholding by tribal communities). Pathalgarhis erected in 2018 have stuck to Hindi, declaring “India Non Judicial” and dismissing voter cards and Aadhaar cards as “anti-Adivasi” documents.

At Laterjang, which set up its Pathalgarhi in 2017, freshly painted wall graffiti repeats these statements — “Lok Sabha na Vidhan Sabha, sab se ooncha Gram Sabha (not Lok Sabha or assembly, gram sabha is the highest authority)” — but other messages make the political climate clear. One sarcastic take says, “Adivasi log gehri neend mein soye huye the. Raghubar Das aur Narendra Modi ne milkar Momentum Jharkhand laaya to yahaan paanchvi anusuchi ka bhoot nikal gaya. Bahut achchha kiya Raghubar Modi ne isliye CM ko bahut bahut dhanyavaad (Adivasis were in deep slumber. CM Raghubar Das and PM Modi together brought investors’ summit Momentum Jharkhand and destroyed the spirit of the Fifth Schedule. We thank the CM),” says another.

In the next lane, as Congress workers distribute NYAY enrolment forms and put up party flags, there is no resistance.

Just like Laterjang, Kochang — a stronghold of the Pathalgarhi movement — has decided to participate in the elections. A year ago, Kochang shot to the headlines after an alleged gang-rape in which Pathalgarhi supporters were implicated. Several arrests followed, including that of a cardinal at the Burudih church. While the government accused the movement of fostering criminal elements, Pathalgarhi supporters saw it as a conspiracy against them.

A week ago, a Congress party office was set up opposite the Pathalgarhi. “Everyone here will vote, just to replace the present government. Under Pathalgarhi, we do not believe in elections, but the kind of repression we faced forced us to change our strategy,” says Kali Munda, a Pathalgarhi leader at Kochang. “The government has tried to take away the rights of indigenous people across the country. It has tried to divide Christians and Sarnas (followers of animism), but we don’t believe we’re different.” Beyond Kochang, the villages of Sakey and Saali are still holding their ground against elections, as is Udburu, the first Pathalgarhi village to set up its own banking system. Just like Kochang, Udburu saw a massive crackdown on its leaders last year.

Areas around arterial roads, like Chitramu or Burudih, have either pulled down the Pathalgarhi or painted over it. Chitramu pulled down its plaque last year, with a ceremony marked by funerary rituals. “Government officials told us we will get access to development schemes if the Pathalgarhi is removed,” says Kishun Swasi, a village elder. Others simply don’t want any more trouble. “We will vote and see if anything changes for us,” says a villager at Alhaudi, where the Pathalgarhi still stands at the village square and has been painted over, but not enough to render the text illegible.