Pulses/ lentils (dal): India

(→2016: Rise in sown area) |

(→2017, Buffer stock) |

||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

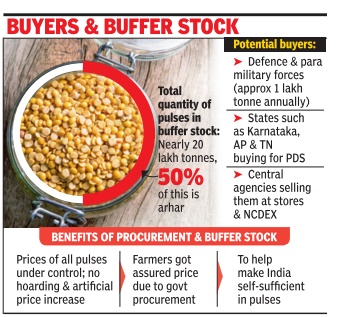

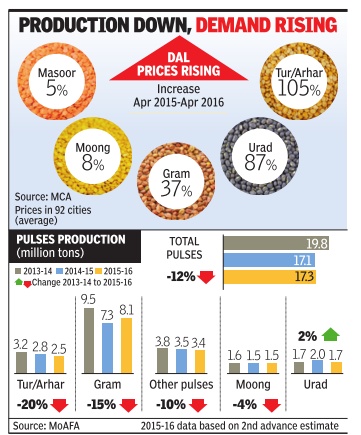

See graphic. | See graphic. | ||

| − | [[File: Buffer stock, 2017, and likely buyers.jpg| Buffer stock, 2017, and likely buyers ; | + | [[File: Buffer stock, 2017, and likely buyers.jpg| Buffer stock, 2017, and likely buyers; [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Gallery.aspx?id=23_04_2017_012_025_012&type=P&artUrl=Forces-may-buy-govts-excess-pulse-stock-23042017012025&eid=31808 The Times of India], April 23, 2017|frame|500px]] |

Revision as of 23:45, 24 April 2017

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Indian food habits

Fading pulse?

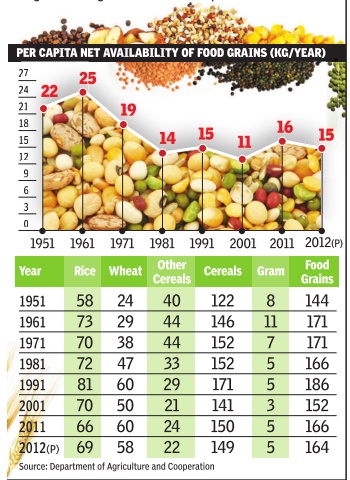

India is by and large a vegetarian country. Recently released NSSO data shows that only 27% of urban and 22% of rural households consumed chicken. Fish was consumed by 21% of urban and 27% of rural households. Mutton was consumed by even fewer people. Thus, for a large majority of Indians, pulses are the major source of proteins. Yet, while the per capita net availability of cereals like rice and wheat is significantly higher today than soon after Independence, availability of pulses is sharply lower, though a little higher than the lowest point reached in 2001

Prices

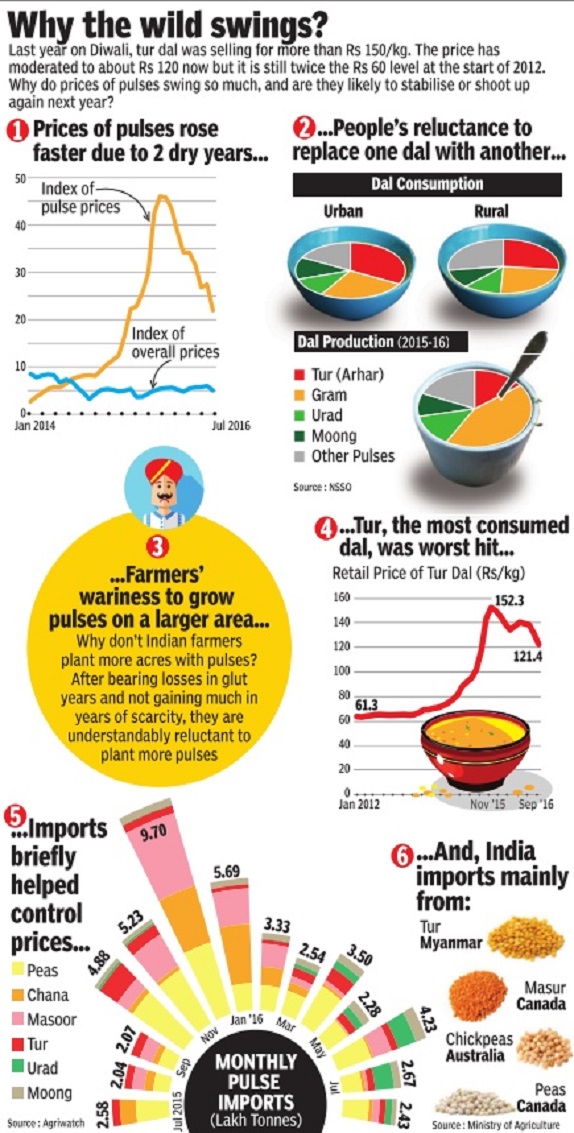

A graphic on this page traces prices from 2012 to mid-2016.

Eating habits and pulse prices

The Times of India

Nidhi Nath Srinivas Sep 30 2016 : The Times of India Your eating habits too are keeping pulse prices high

Why have pulses become so expensive over the past two years? The easy answer is scarcity. Two consecutive dry years hit production in India and eroded stocks while bad weather in the other major producers--Canada, Australia, Africa and Myanmar--reduced room for imports in 2015-16.

But equally, the price hike is a result of our palate. You cannot make sambhar with chana nor eat bhatura with tur dal.Even if our favourite dal becomes scarce and unaffordable, we don't substitute it with a cheaper option.

There are regional preferences: Uttar Pradesh likes sabut masoor and Punjab loves sabut urad, while the rest of India stays away from `kali' dal. Rajasthan eats the small desi chana but Madhya Pradesh and Punjab use the bigger `dollar' chana and white kabuli chana. Even millers are choosy about the type of chana they process into `besan' for snacks and namkeen.

The third important reason for price rise is farmers' reluctance to plant more acres with pulses despite the seeming scope for immense profit in crisis years.But over the years, they have too often suffered losses when prices crash while receiving little extra when prices rise.Only when they are convinced that they will not suffer in years of plenty will farmers adopt smart techniques to increase yields of each pulse type.

And so India continues lurching between shortage and severe shortage of pulses. However, the outlook for the next one year now seems brighter. Weather has turned favourable in Canada and Australia. Tur, moong and chana are now available in the world market below our average minimum support price of Rs 50kg. The wholesale markets are reacting to this fall. Farmers have also responded to the higher prices and good rains this summer by planting pulses on 29% more area. Prices at grocery shops will eventually fall in line.

(Chief Marketing Officer, NCDEX)

2015: Price rise

The Times of India, Oct 17 2015

Subodh Varma

Why pulses are on fire: India's food math explained

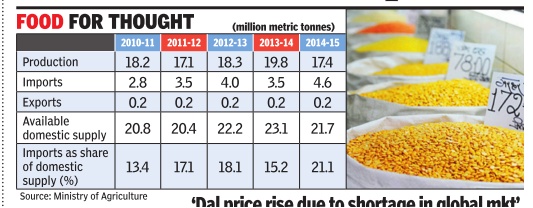

Where does a 12% decline translate as a 100% increase? In the bizarre world of India's food math. Production of pulses slipped down by 12% in 2014-15 compared to the previous year. As a result, prices of this essential item have zoomed up by more than 100% across the country . The government is scrambling to retrieve the situation, especially because an important election is being fought in Bihar and the festive season is just beginning. It's a kind of an onion moment -where merciless spikes in onion prices in the past led to political upheavals. But why are pulses on fire? Here are the basics: India consumes around 23 million metric tonnes (MMT) of pulses. This is an aggregate of a variety of pulses including gram (chana), tur or arhar, mung, masur and urad.Pulses are the main source of protein for a very large number of people in the country -each 100 grams contain about 32 grams of proteins and several amino acids not made by the body . So, it is an essential part of Indian meals. Naturally , India is the largest producer and consumer of pulses in the world. But India's production of pulses has stagnated at around 18-19 MMT for several years now. The shortfall between production and consumption is made up by imports, mainly from Canada, Myanmar and some African countries. This balance has been maintained at a huge cost to the people. A population growing at the rate of about 2% per year in the past decade should have quickly overtaken the pulses rate of growth which was less than half of that. This has not happened because the amount of pulses consumed per person has relentlessly declined over the past several decades.From about 61 grams per person per day in 1951 to about 42 grams in 2013. The balance this year has been rudely and dramatically upset. In 2014-15, production of pulses was clocked in at 17.4 MMT -a decline of 2.4 MMT or 12% over the previous year. This was caused by various factors including unseasonal rains, pests, and unprofitable prices offered to farmers even as import duties were waived. This decline appears to have been seized as an opportunity to make a quick killing by traders -both domestic and global. There are reports of pulses stocks lying in warehouses at ports as traders wait it out and allow shortages to pump up prices even more. And, exporters in touch with producers from Canada (mainly lentil or masur), Myanmar (mainly tur) and Australia (mainly chickpeas or Kabuli chana) have hiked up the rates because India is the biggest player in the pulses import market. So, in 2014-15, India has imported 4.6 MMT pulses, up by 31% compared to the pre vious year. International prices have risen in tandem from Rs 32 per kg to Rs 50 for chana, from Rs 56 to Rs 75 for lentil, from Rs 40 to Rs 90 for tur, and from Rs 50 to Rs 77 for urad between October 2014 and August 2015, according to the latest agriculture ministry profile. The government on its part is tinkering around at the periphery by ordering about 7000 metric tonnes of pulses in the international market and “invoking“ the Rs 500 crore price stabilization fund to subsidise transport of pulses stocks from ports to retailers. In a country that consumes over 6000 metric tonnes of pulses every day , this can hardly be expected to bring down prices. Experts have called for a new impetus to pulses production with new seeds, better pest control, better support prices and a much better organised market so that the future expected requirement of pulses can be met. Otherwise India faces a protein famine in the coming years. `Dal price rise due to shortage in global mkt' The government on Friday attributed the sharp rise in prices of pulses to shortage in the global market and increased prices across the major producing countries. Minister of state for agriculture Sanjeev Balyan said less production last year led to the gap between availability and demand. The agriculture ministry officials refuted charges of delay on their part in importing arhar and urad. Balyan said starting the next harvest season (from November), the government will buy 40,000 tonnes of pulses from farmers to create a buffer stock to control prices. Dipak Dash

Right steps can rein in onion prices: Niti

Niti Aayog has suggested that the volatility in onion prices can be managed through appropriate mechanism and intervention as past price trends show a clear pattern in price spikes and high prices rule only for a few months. NitiAayog member Ramesh Chand said, “These measures include enhancing of storage infrastructure, stocking of onion by central agencies like Nafed, state-level entities and public parastatals .“

The Aayog also slammed previous governments for ineffective response. Chand said, “Till recently, any abnormal rise in onion price was attributed to unfavourable weather and exploitation of situation by traders and so called cartelization, hoarding etc and it was forgotten when prices rolled back to normal.“

Production and consumption of cereals, pulses

The Times of India, Oct 26 2015

Rajeev Deshpande & Dipak Kumar Dash

Dals not given priority in MSP, Food Security Act

Cereal-driven policies reason behind galloping pulse prices'

The current spike in pulse prices could have been anticipated, but India's cerealcentric food security policies emphasise rice and wheat while dis-incentivising the production of pulses despite clear trends that show a declining preference for cereals. Even though India's dependency on imported pulses grew as imports rose from 2.7 million tonnes (MTs) in 2010-11 to over 4 MTs this year, minimum support price-driven procurement and the Food Security Act's commitment of 61 MTs a year drove cereal production despite overflowing godowns.

The MSP policies have resulted in buffer stocks of 61 MTs, largely rice and wheat, as of June this year some 20 MTs more than the strategic reserve of 40 MTs. Though the NDA government has moderated the yearly increase in MSP , procuring cereals remains priority for the Centre and states.

The situation presents a widening demand-supply mismatch as while per capita consumption of cereals declined in both urban and rural areas (see chart), the demand for other protein food is rising, indicating emerging preferences for “high value“ food across all income segments according to National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) consumption expenditure data.

Analysis of NSSO data from 1993-94 to 2011-12 across three income segments the 10-30, 30-70 and 70-100 deciles broadly representing the lowest, middle and high income groups show the trend clearly .The monthly per capita consumption of cereals declined 8.2% in the lowest decile, 16.5% in middle decile and 21.6% in the highest in rural areas. The decline in per capita consumption of cereals makes a strong case for more targeted support to the most needy rather than the food security scheme's coverage of 67% of the population or an estimated 82 crore individuals -more than thrice the number of people below the official poverty line.

According to NSSO data, while consumption of cereals (as a proportion of proteins) fell from 69.42% to 62% in rural areas between 1993-94 and 2011-12, consumption of pulses went up from 9.76% to 10.57%.The trend was even more pronounced in urban areas.

At the same time, production of pulses fluctuated between 17.09 MTs and 19.2 MTs during 2010-11 and 2013-14. During 2014-15, it was 17.38 tonnes against the domestic requirement of about 22 MTs. The government estimates the production to increase to 18.32 MTs as the sown area has risen from 10.2 million hectares in 2014 to 11.5 million hectares in 2015.

2016: Rise in sown area

The Times of India, Sep 03 2016

Vishwa Mohan

33% rise in sown area boosts hopes of dip in pulse prices

It may take time for India to be self-sufficient in meeting its domestic demand of pulses, but the ongoing kharif sowing season has sent a reassuring signal as farmers have opted for their cultivation in a big way in many parts of the country . Figures, released by the Union agriculture ministry, show a significant jump in coverage area under pulses, an indication that the price of the most popular source of protein in India is set to fall post-harvest when higher production compensates for the supply side shortfall.

Total sown area under pulses has increased from 106.92 lakh hectares at this time last year to 142.02 lakh hectares as on Friday , a rise of nearly 33%. If compared to the usual average sown area under pulses at this time of the season (102.01 lakh hectares), it recorded an increase of over 39% this year.

Arhar (tur dal or pigeon pea) which recorded the maximum price rise has, in fact, led the pack of pulses in terms of coverage.

Experts believe that the enthusiasm of farmers towards pulses can be attributed to an increase in minimum support price (MSP) as the cultivators see the prospect of better returns.

As a result of good sowing season, the agriculture ministry expects a record production of pulses (20 million tonnes) in 2016-17, the highest since 1957.

Though the country will still have to depend on import to meet the domestic demand, higher production is expected to soften retail prices.

Though the other kharif crops, rice, coarse cereals and oilseeds, too recorded increases in their respective sown areas, the rise in such cases was only marginal.Other crops like cotton, sugarcane and jute, on the other hand, recorded a decline as compared to 2015.

Overall, the total sown area for all kharif crops together stands at 1,033.99 lakh hectares on Friday as compared to 997.11 lakh hectares at this time last year, an increase of a mere 3.7% over 2015, which was the drought year.

Sowing of kharif crops begins with the onset of south-west monsoon from June and continues till midSeptember. Harvest generally starts in October, mainly for the crops which are sown in June.

Availability of water in reservoirs also signals the prospect of a better season for rabi crops during the winters.

According to the central water commission (CWC) data, the water storage available in 91 major reservoirs of the country was 105.248 billion cubic meter (BCM) as on Thursday , which is 67% of total storage capacity of these reservoirs and 114% of the storage of corresponding period of last year.

The water availability in these reservoirs will keep on increasing till the end of monsoon season (September end), giving hope for a bumper rabi crop since it largely depends on irrigation.

2017, Buffer stock

See graphic.