Rabindranath Tagore

(→2015: Chinese translation draws ire) |

(→2015: Chinese translation draws ire) |

||

| Line 306: | Line 306: | ||

Tagore, who had visited China thrice, has a fanatical following in the country. | Tagore, who had visited China thrice, has a fanatical following in the country. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Chinese author: Feng Tang== | ||

| + | [http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/feng-tang-lost-in-translation/1/564317.html ''India Today''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Best-selling Chinese author Feng Tang on what the uproar in China about his new translation of Tagore's 'Stray Birds' says about the limits of expression.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | When Feng Tang, one of China's most popular writers, decided to begin in the summer of 2014 a three month-long project translating the poems of Rabindranath Tagore, it was meant to be a welcome escape. For two decades, Feng has been one of China's most controversial writers. | ||

| + | His six novels, three essay collections and one work of poetry have been read by millions. His widely-read trilogy that presented a no-holds-barred look at growing up in a changing Beijing established Feng as a voice for the youth-and as an irreverent, even subversive, writer who told it like it is; a writer who spoke in the language of the people, writing vividly of youth discovering sex and poking fun at Communist dogmas, a writer who did not dress up his often profanity-littered language in the formalities beloved by the political establishment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But little did Feng expect that his translation of 'Stray Birds', a collection of 300-odd short verses penned by Tagore in 1916, would turn out to be perhaps his most controversial. In early December, a number of commentaries in the Chinese State-run press took aim at Feng, accusing him of 'vulgarity' and of blaspheming the Indian poet, who has been revered in China as a saintly 'poet-sage' figure since his 1920s Shanghai visit. | ||

| + | The English-language government mouthpiece, China Daily, published an extraordinary commentary by its film critic, Raymond Zhou, describing Feng's translation as a 'vulgar selfie'. Zhou called him a 'hormone-obsessed' writer with a 'colossal insecurity'. The Party mouthpiece, People's Daily, penned a similar commentary, rattling the publishers who on December 28 took the unprecedented step of removing Feng's translation from all the shelves of bookstores across the country. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Unwrapping Tagore''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | This storm of anger has left Feng puzzled. "Out of 326 poems," he says, "it is just three verses, and in those only five words, that they are upset about." The commentaries all pointed to three specific translations. In the first instance, where Tagore writes, 'the great earth makes herself hospitable with the help of the grass', Feng in Chinese used a more suggestive word for hospitable that means coquettish or flirtatious. In the second instance, where Tagore writes of the world removing its 'mask of vastness to its lover' and becoming 'one kiss of the eternal', Feng interprets this verse sexually, speaking of a world removing its 'underwear of vastness' and one 'French kiss of the eternal'. The third offence was Feng's use of a colloquial Chinese character, used by young Internet users, instead of a formal article, seen by some critics as disrespecting Tagore. | ||

| + | "Most of the people criticising the book only read those three poems," says Feng. He says most of the 323 other verses have been rendered more faithfully, and are more similar to Tagore's original haiku-like verse than the widely used translation, done by Chinese writer Zheng Zhenduo in the 1920s. "When Zheng translated Tagore, the modern Chinese language he was using was at an early stage so it actually feels awkward in many places." Feng says he wanted to more closely reflect Tagore's own brevity. For instance, where Tagore writes, 'O Beauty, find thyself in love, not in the flattery of thy mirror', Feng uses only 8 Chinese characters to rather neatly capture the verse, in comparison with Zheng's rather flowery 23. | ||

| + | Not everyone shares his opinion. The work has divided China's literary world, to some extent on generational lines. Many older scholars have been appalled by his sexualised rendering. One Chinese academic who has been translating Indian works for two decades said it was "good that Feng's unprofessional work" was taken off the shelves. His view was shared by a Chinese Indologist in Beijing who said his work was needlessly "crude". | ||

| + | On the other hand, many younger Chinese writers have come to his support, expressing outrage at the move to remove his books from the shelves-all because the sensibilities of some scholars and critics were offended. Even if Feng was 'vulgar', they argue, his right to expression shouldn't have been curtailed. Leading Chinese sociologist Li Yinhe, who has written pioneering studies on sex in China, praised Feng, saying his version "was not bad but just a version where the translator's individual style is strong." In her view, Feng's version was 'the best Chinese translation so far.' Several writers, including the prominent feminist writer Liu Liu who praised his interpretation as 'fantastic', have taken to Chinese social media to defend Feng, where, especially from his 8 million followers, he's received more bouquets than brickbats. | ||

| + | Priyadarsi Mukherji, professor in Chinese language, literature and culture studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, says he can, to some extent, understand the ire of Feng's critics. "There were two or three poems that come across as obscene in the translation," he says. | ||

| + | Mukherji, however, adds that he had an 'open mind' about Feng's interpretation and some of the other poems were, in fact, rendered well. | ||

| + | Rather than 'merely criticising' Feng, Mukherji was hoping 'to engage him in dialogue so he can explain his choices and interpretations'. Feng was scheduled to speak with Mukherji at the New Delhi World Book Fair on January 11. | ||

| + | This controversy, however, has forced him to pull out, after the Chinese partners in the event, the China National Publications Import & Export Company, the biggest official publishing company, advised Feng to not go to India. Feng is saddened he cannot travel, more so by "the labelling of the entire work as vulgar", including by Indian media. When the China Daily published the article, it was picked up by Indian media outlets which Feng notes faithfully reproduced as fact the accusation that his entire work was 'vulgar' without either reading the other poems or bothering to speak to him. He has since received death threats from Indian Internet users. Whether it was the reaction in India or the Chinese State media's campaign against Feng that prompted the official publishers to cancel his trip is unclear. | ||

| + | Feng says his translation-and the reaction-have been illuminating. | ||

| + | One reason for the anger is that as schoolchildren read Tagore, Feng has been accused of trying to corrupt them by sexualising the revered poet. | ||

| + | Another reason, he suggests, is that Chinese tend to worship their writers and philosophers, whether Confucius or Tagore. "They want to see Tagore as a saintly figure. But his verse is not soft, gentle, a children's book as people in China think. He also speaks of love, and of making love. He writes also of darkness: 'I am none of the wheels of power but I am one with the living creatures crushed by it'. Do they think children will understand this?" | ||

| + | |||

| + | Beyond 'Stray Birds', the uproar, Feng says, reflects the unease in China with anyone who swims against the current. "Tagore himself was irreverent, and not someone who liked worship. What makes me uncomfortable is how they can decide what it is that Tagore meant. People hate to have something that challenges their historical view of things. The tree should be green. The flower should be red. If I write about a yellow flower, wrong! Change the colour back to red! It surprises me after so many years in this modern economy, of opening up, so little has changed." | ||

Revision as of 17:59, 18 February 2016

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

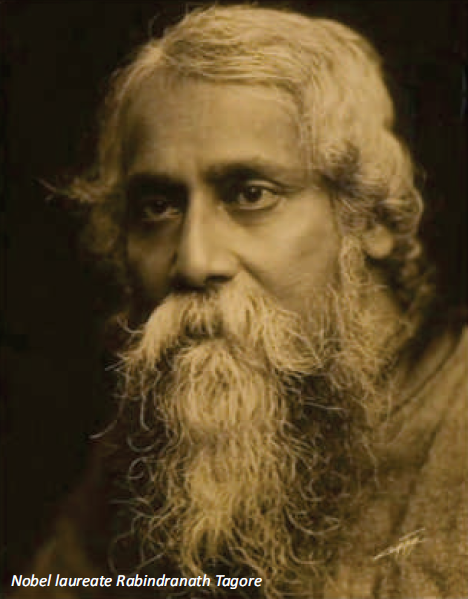

A profile

A new India free from the conflict of communities

By Uma Dasgupta

India Harmony VOLUME - 1 : ISSUE – 3 APRIL, 2012

It is hard to put a person's vision into words. There is something a little ephemeral about visions. But Tagore was different. He did not just speak or write of his vision for the future. He worked for it all his life.

A cosmopolitan almost by instinct, Tagore worked hard from the fortieth year of his life till the end to build experimental and felt communities based on the universal truths of civilisation where there would be no scope for domination of any one culture over another. There would only be learning from each other's cultures and lifeexperiences leading to a meeting of minds or a human brotherhood of the world's races. 'Truth does not know of East and West', wrote Tagore, in his essay on “Ideals of Education”.

In exploring the roots of his almost intuitive cosmopolitanism, He believed keenly that India's history grew out of a social civilization where every attempt was made to evolve a human adjustment of peoples and races. In his writings on Indian history he confidently argued that even though 'race conflict' was his country's historic problem, efforts towards unity was his country's ideal or sadhana. He identified this sadhana as an ethical code of conduct that became the most crucial factor in preserving the unity of India for centuries. Otherwise, its truth would have been obscured.

In this history of living within the differences Tagore saw an ideal of unity that he hoped might transcend into India's and Asia's contribution to the Modern Age where the scientific facility had brought the human races closer but not without their baggage of psychological barriers. He insisted that the psychology of the world had to change in order to meet the new environment of the new age. Europe was at the time conceiving of a League of Nations. Tagore wrote enthusiastically that this was a momentous period for India and Asia to restore their spirit of cooperation in culture and heal the suffering peoples of the modern age from the divisive politics and materialistic greed which were vitiating even the citadels of education. He called for the study of histories and cultures as a rational way of fighting the forces of war and aggression. He spoke out for the need of higher ideals in politics to save humanity. He wrote, 'Even though from my childhood I have been taught that idolatry of the nation is almost better than reverence for God and humanity, I believe I have outgrown that teaching, and it is my conviction that my countrymen will truly gain their India by fighting against [emphasis his] the education which teaches them that a country is greater than the ideals of humanity'.

This humanism was also a response to what he identified as the ideal source books of India's history. His strong imagination and his sense for a people's history took him to his country's epic literature in the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and the Puranas for an understanding of India's unified culture arguing that the epics tell us about a larger synthesis in Indian society and culture. He interpreted this synthesis as a victory of the religion that broke away from Brahmin orthodoxy by relegating to a secondary place the ceremonials or rituals for avenging injury or acquiring merit. He reckoned this breakthrough was Brahmavidya, knowledge of the Supreme Truth, the worship of love between God and man and their spiritual unity. 'Unless we have this history', wrote Tagore, 'the true picture of India will remain only partially known to her children and such partial knowledge might be very erroneous.'

Tagore's mentor in this remarkable striving was Rammohan Roy who was the first leader of modern India to realize the fundamental unity of spirit in the Hindu, Muslim, and Christian cultures. 'Rammohan represented India in the fullness of truth, based not upon rejection but on perfect comprehension', wrote Tagore. 'I follow him', he added, 'although he is practically rejected by our countrymen.'

There was also in Tagore's background the other remarkable man of those times, his grandfather Prince Dwarkanath, who was the first independent merchant of British India. As middlemen in a trading world the Tagore family willingly allied themselves with European merchants in banking and insurance believing that was good for their country and its future. When examining the family's history one is left without doubt that these pioneers, (or the “Calcutta Medici” as they have been described by historians), established the material foundation of a society which was at ease with high British culture, and which held their own solidly in British-Indian commerce, and all along grew in strength as cultural nationalists. With them there was an advent of new ideals, which at the same time were as old as India.

All of these formative influences of looking beyond narrow domestic walls went into the making of the Santiniketan school and Visva- Bharati international university. It was hoped that the institution's holistic values imparted through a new and alternative education would help to build a new Indian personality free from the conflict of communities and capable of appreciating the many currents of the Indian cultural tradition along with the humanistic and liberal values of the West. The new Indian personality would belong neither to the East nor to the West, but be a reconciler of both.

Tagore wrote, 'The India of modern days comprised not only the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain, whose common culture had its origin in India itself, but also the Mohammadan with his wonderful religious democracy of semitic origin and the Christian with his political democracy nurtured in Europe. There was also in India the Parsi from whom we had parted long ago outside the boundaries of India but who had come back to us again ... If Santiniketan was to become truly the guest house of India it had to be so comprehensive as to find room for each and all of these in its ripest scholarship. The treasures which these different religious cultures contained should be brought into practical use in relation to the modern world, not held apart and miserly hoarded'. Tagore gave an important place in Visva-Bharati's research agenda to studying also the life-histories of the medieval sages of India such as Kabir, Nanak, Dadu, Ruidas and others who broke through barriers of social and religious exclusiveness and brought together India's different communities on the genuine basis of spiritual idealism. He honoured them as the 'people's saints'. They swept the country with a progressive movement by their spontaneous message – 'he alone knows Truth who knows the unity of all beings'.

A poem from his Gitanjali, titled India's Prayer in its English translation, is a powerful statement of his hope for a future cleansed of divisive and nationalist politics. The words are,

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Where knowledge is free; Where the world has not been broken up into narrow domestic walls; Where the words come out from the depth of truth; Where tireless striving stretches its arms into perfection; Where the clear stream of reason Has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit; Where the mind is led forward By Thee into ever-widening thought and action Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, Let my country awake.

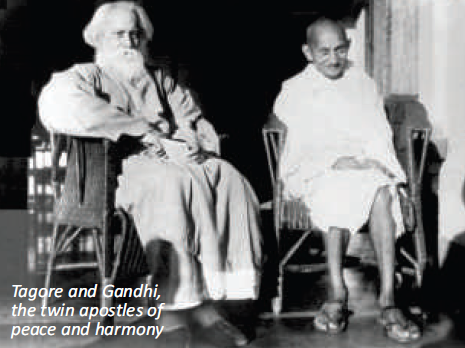

Clearly, there was a longing quest in this poem for an enlightened future for his country. Indeed, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru acknowledged his ideas for a liberal and secular democracy as crucial in shaping India's future particularly in the inter-War years. Yet, for most of the past century, while Tagore was celebrated, his cosmopolitan educational project in Santiniketan was ignored and marginalized by the imperatives of a competitive capitalism and nationalism. There are several areas where I believe Tagore was limited by both the historical forces of his time and his own particular approach. But that cannot diminish the relevance of his vision for the future and some of his strategies for our own time. From the point of view of contemporary global history too, which numerous scholars across the disciplines of political and social sciences have rightly perceived as having entered a new cycle of imperialism, Tagore's ideals offer much scope for important reappraisal. In some ways this is happening in his 150th year when many of the symposia being held in his memory are addressing his ideas and addressing and raising the question of their global relevance today. These symposia are taking place in India and in the Western countries. Unesco is currently preparing a document titled “A Reconciled Universal” by drawing from the works of Tagore, Neruda and Césaire -- Three Humanist Poets of the South in the words of Unesco's Project -- by projecting their individual messages beyond their particular significance and striking a chord more deeply together than singly in building a humanist platform, for an alliance between civilizations, to counter the heightened pressure of economic, political, social, environmental, religious and cultural ruptures and tensions of today.

Finally, let us ask ourselves: today we have roads, four way roads, quadrilaterals, flyovers, bypasses. But bridges? We lack those. We lack the hand that will say 'hullo, what is all this?' Surely, something is wrong. Something is missing. We see but do not notice. We hear but do not listen. We have lost the human touch in the embrace of systems, lost the human face in the gallery of assembly line digits. We plan, but do we feel?

Tagore had a vision for the future, and did what he could for it singlehandedly, because he felt strongly. Perhaps that could be his legacy at least in our personal lives as we honour him in his 150th year. I sense that the organizers of this Tagore Festival have felt a commitment to his legacy in this effort to re-visit Tagore's ideals and the creative unity of his cultural gifts to humanity, and thus to enrich the communities in this large and vibrant city of Los Angeles. I am very grateful to have been able to participate in this effort.

Mining, corruption and gurudev

The Times of India, Aug 8, 2011

Tapan Chatterjee

Mining scandals are rocking the country and daily news reports bring to light more cases of corruption among politicians and businessmen and their total apathy towards the environment and life. However, 72 years ago mining had found a strong proponent in Rabindranath Tagore – as long as it was within limits and kosher, of course. The protagonist in his short story ‘Parting Words’ (Sesh Katha) had conveyed his “Salam to Jamsetji Tata” for the latter’s pioneering effort in mining and setting up a steel factory in 1912. The village Sakchi, where iron ore was first found five years earlier, became Jamshedpur, now a thriving town that is an industrial hub.

The story’s protagonist, Nabinmadhav, castigates the dysfunctional posse of English civilians for their “excessive preoccupation with law and order”. He deprecates, “They had once indulged in indigo cultivation, then they switched to tea plantation…but had utterly failed to explore the huge assets buried deep within Bharat, be it in the hearts and minds of her people, or be it within her nature.”

He further notes, “Deep within her hard-toreach womb, the earth keeps stored tough metals that powerful ones have used to conquer the four winds”. Nabin observes, “The poor have remained contented only with the produce of the earth’s topsoil – crops; and in the process their stomachs have dried out, their ribs gone skeletal.” Hence, Nabin changed his job, learnt mining and became a geologist.

Tagore wrote his last three short stories at the age of 78. Of a different genre, these were compiled in the book, Three Associates. The three protagonists of these stories were professionals of science or engineering to presage industrialisation to the new generation.

But before someone even thinks of loading his trucks with illegally mined ores, he must stop in his tracks and reflect a bit on why he is doing what he is doing and what the consequences of such an action could be.

Illegal mining is the consequence of self-aggrandisement that comes from unbridled greed. Quoting the Upanishad, Tagore had repeatedly advocated ma gridhah, meaning “Do not greed!”

He had reasoned, “Why we must not give in to greed? Everything is pervaded by One Truth. Therefore, an individual’s greed prevents us from realising that One. Tena tyaktena bhunjeethah – let a l l benefit from what emanates from that One…ma gridhah kashyaswiidhanam, that is, do not covet another’s wealth.” Manifested as corruption, greed is gnawing at the entrails of our nation. We need to stop this here and now, without giving in to self-despair. When greed overtakes need, it spells trouble. Tagore wrote his famous song ‘Ekla Chalo’ (walk alone) during the days of national crisis so as to enthuse one and all to make the call of their inner conscience as paramount.

The monsoon is here once again, bringing with it welcome rain. What else can one pray for but renewal and rejuvenation? It’s time to sow seeds of hope for a better tomorrow. It’s also an opportune time to renew our social contact by cleansing our conscience and spreading hope. And it’s a good time to invoke the words of Gurudev as we celebrate 150 years of his birth. Just three months before his death – on his last birthday – Tagore had emphatically declared, “It’s a sin to lose faith in man.”

2015: Chinese translation draws ire

The Times of IndiaDec 22 2015

Beijing

A Chinese writer has translated Rabindranath Tagore's works with “vulgar“ sexual connotations, drawing sharp condemnation from the admirers of the Nobel laureate in China who termed it as an attempt to gain popularity.

“There's a fine line between imprinting creative works with unique personality and screaming for attention,“ columnist Raymond Zhou wrote in state run China Daily, criticising the writer, Feng Tang, who has published the new translations. “Feng just crossed it, when he translated Tago re's tranquil verse in to a vulgar selfie of hormone saturated innuendo,“ Zhou wro te in his column titled `Lust in translation'.

He said the translation is “for ridicule rather than for appreciation“.

Tagore, who had visited China thrice, has a fanatical following in the country.

Chinese author: Feng Tang

Best-selling Chinese author Feng Tang on what the uproar in China about his new translation of Tagore's 'Stray Birds' says about the limits of expression.

When Feng Tang, one of China's most popular writers, decided to begin in the summer of 2014 a three month-long project translating the poems of Rabindranath Tagore, it was meant to be a welcome escape. For two decades, Feng has been one of China's most controversial writers. His six novels, three essay collections and one work of poetry have been read by millions. His widely-read trilogy that presented a no-holds-barred look at growing up in a changing Beijing established Feng as a voice for the youth-and as an irreverent, even subversive, writer who told it like it is; a writer who spoke in the language of the people, writing vividly of youth discovering sex and poking fun at Communist dogmas, a writer who did not dress up his often profanity-littered language in the formalities beloved by the political establishment.

But little did Feng expect that his translation of 'Stray Birds', a collection of 300-odd short verses penned by Tagore in 1916, would turn out to be perhaps his most controversial. In early December, a number of commentaries in the Chinese State-run press took aim at Feng, accusing him of 'vulgarity' and of blaspheming the Indian poet, who has been revered in China as a saintly 'poet-sage' figure since his 1920s Shanghai visit. The English-language government mouthpiece, China Daily, published an extraordinary commentary by its film critic, Raymond Zhou, describing Feng's translation as a 'vulgar selfie'. Zhou called him a 'hormone-obsessed' writer with a 'colossal insecurity'. The Party mouthpiece, People's Daily, penned a similar commentary, rattling the publishers who on December 28 took the unprecedented step of removing Feng's translation from all the shelves of bookstores across the country.

Unwrapping Tagore

This storm of anger has left Feng puzzled. "Out of 326 poems," he says, "it is just three verses, and in those only five words, that they are upset about." The commentaries all pointed to three specific translations. In the first instance, where Tagore writes, 'the great earth makes herself hospitable with the help of the grass', Feng in Chinese used a more suggestive word for hospitable that means coquettish or flirtatious. In the second instance, where Tagore writes of the world removing its 'mask of vastness to its lover' and becoming 'one kiss of the eternal', Feng interprets this verse sexually, speaking of a world removing its 'underwear of vastness' and one 'French kiss of the eternal'. The third offence was Feng's use of a colloquial Chinese character, used by young Internet users, instead of a formal article, seen by some critics as disrespecting Tagore. "Most of the people criticising the book only read those three poems," says Feng. He says most of the 323 other verses have been rendered more faithfully, and are more similar to Tagore's original haiku-like verse than the widely used translation, done by Chinese writer Zheng Zhenduo in the 1920s. "When Zheng translated Tagore, the modern Chinese language he was using was at an early stage so it actually feels awkward in many places." Feng says he wanted to more closely reflect Tagore's own brevity. For instance, where Tagore writes, 'O Beauty, find thyself in love, not in the flattery of thy mirror', Feng uses only 8 Chinese characters to rather neatly capture the verse, in comparison with Zheng's rather flowery 23. Not everyone shares his opinion. The work has divided China's literary world, to some extent on generational lines. Many older scholars have been appalled by his sexualised rendering. One Chinese academic who has been translating Indian works for two decades said it was "good that Feng's unprofessional work" was taken off the shelves. His view was shared by a Chinese Indologist in Beijing who said his work was needlessly "crude". On the other hand, many younger Chinese writers have come to his support, expressing outrage at the move to remove his books from the shelves-all because the sensibilities of some scholars and critics were offended. Even if Feng was 'vulgar', they argue, his right to expression shouldn't have been curtailed. Leading Chinese sociologist Li Yinhe, who has written pioneering studies on sex in China, praised Feng, saying his version "was not bad but just a version where the translator's individual style is strong." In her view, Feng's version was 'the best Chinese translation so far.' Several writers, including the prominent feminist writer Liu Liu who praised his interpretation as 'fantastic', have taken to Chinese social media to defend Feng, where, especially from his 8 million followers, he's received more bouquets than brickbats. Priyadarsi Mukherji, professor in Chinese language, literature and culture studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, says he can, to some extent, understand the ire of Feng's critics. "There were two or three poems that come across as obscene in the translation," he says. Mukherji, however, adds that he had an 'open mind' about Feng's interpretation and some of the other poems were, in fact, rendered well. Rather than 'merely criticising' Feng, Mukherji was hoping 'to engage him in dialogue so he can explain his choices and interpretations'. Feng was scheduled to speak with Mukherji at the New Delhi World Book Fair on January 11. This controversy, however, has forced him to pull out, after the Chinese partners in the event, the China National Publications Import & Export Company, the biggest official publishing company, advised Feng to not go to India. Feng is saddened he cannot travel, more so by "the labelling of the entire work as vulgar", including by Indian media. When the China Daily published the article, it was picked up by Indian media outlets which Feng notes faithfully reproduced as fact the accusation that his entire work was 'vulgar' without either reading the other poems or bothering to speak to him. He has since received death threats from Indian Internet users. Whether it was the reaction in India or the Chinese State media's campaign against Feng that prompted the official publishers to cancel his trip is unclear. Feng says his translation-and the reaction-have been illuminating. One reason for the anger is that as schoolchildren read Tagore, Feng has been accused of trying to corrupt them by sexualising the revered poet. Another reason, he suggests, is that Chinese tend to worship their writers and philosophers, whether Confucius or Tagore. "They want to see Tagore as a saintly figure. But his verse is not soft, gentle, a children's book as people in China think. He also speaks of love, and of making love. He writes also of darkness: 'I am none of the wheels of power but I am one with the living creatures crushed by it'. Do they think children will understand this?"

Beyond 'Stray Birds', the uproar, Feng says, reflects the unease in China with anyone who swims against the current. "Tagore himself was irreverent, and not someone who liked worship. What makes me uncomfortable is how they can decide what it is that Tagore meant. People hate to have something that challenges their historical view of things. The tree should be green. The flower should be red. If I write about a yellow flower, wrong! Change the colour back to red! It surprises me after so many years in this modern economy, of opening up, so little has changed."