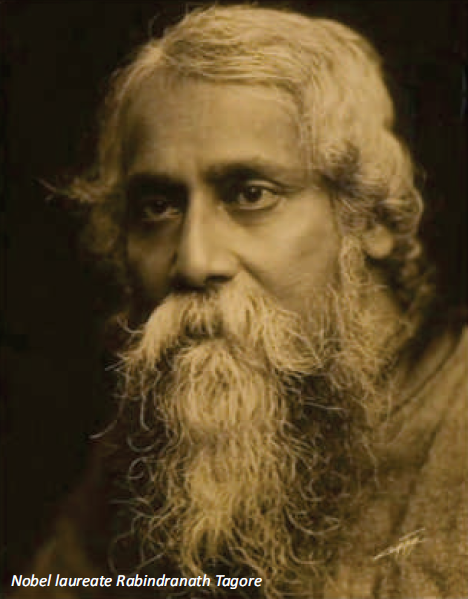

Rabindranath Tagore

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

A profile

A new India free from the conflict of communities

By Uma Dasgupta

India Harmony VOLUME - 1 : ISSUE – 3 APRIL, 2012

It is hard to put a person's vision into words. There is something a little ephemeral about visions. But Tagore was different. He did not just speak or write of his vision for the future. He worked for it all his life.

A cosmopolitan almost by instinct, Tagore worked hard from the fortieth year of his life till the end to build experimental and felt communities based on the universal truths of civilisation where there would be no scope for domination of any one culture over another. There would only be learning from each other's cultures and lifeexperiences leading to a meeting of minds or a human brotherhood of the world's races. 'Truth does not know of East and West', wrote Tagore, in his essay on “Ideals of Education”.

In exploring the roots of his almost intuitive cosmopolitanism, He believed keenly that India's history grew out of a social civilization where every attempt was made to evolve a human adjustment of peoples and races. In his writings on Indian history he confidently argued that even though 'race conflict' was his country's historic problem, efforts towards unity was his country's ideal or sadhana. He identified this sadhana as an ethical code of conduct that became the most crucial factor in preserving the unity of India for centuries. Otherwise, its truth would have been obscured.

In this history of living within the differences Tagore saw an ideal of unity that he hoped might transcend into India's and Asia's contribution to the Modern Age where the scientific facility had brought the human races closer but not without their baggage of psychological barriers. He insisted that the psychology of the world had to change in order to meet the new environment of the new age. Europe was at the time conceiving of a League of Nations. Tagore wrote enthusiastically that this was a momentous period for India and Asia to restore their spirit of cooperation in culture and heal the suffering peoples of the modern age from the divisive politics and materialistic greed which were vitiating even the citadels of education. He called for the study of histories and cultures as a rational way of fighting the forces of war and aggression. He spoke out for the need of higher ideals in politics to save humanity. He wrote, 'Even though from my childhood I have been taught that idolatry of the nation is almost better than reverence for God and humanity, I believe I have outgrown that teaching, and it is my conviction that my countrymen will truly gain their India by fighting against [emphasis his] the education which teaches them that a country is greater than the ideals of humanity'.

This humanism was also a response to what he identified as the ideal source books of India's history. His strong imagination and his sense for a people's history took him to his country's epic literature in the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and the Puranas for an understanding of India's unified culture arguing that the epics tell us about a larger synthesis in Indian society and culture. He interpreted this synthesis as a victory of the religion that broke away from Brahmin orthodoxy by relegating to a secondary place the ceremonials or rituals for avenging injury or acquiring merit. He reckoned this breakthrough was Brahmavidya, knowledge of the Supreme Truth, the worship of love between God and man and their spiritual unity. 'Unless we have this history', wrote Tagore, 'the true picture of India will remain only partially known to her children and such partial knowledge might be very erroneous.'

Tagore's mentor in this remarkable striving was Rammohan Roy who was the first leader of modern India to realize the fundamental unity of spirit in the Hindu, Muslim, and Christian cultures. 'Rammohan represented India in the fullness of truth, based not upon rejection but on perfect comprehension', wrote Tagore. 'I follow him', he added, 'although he is practically rejected by our countrymen.'

There was also in Tagore's background the other remarkable man of those times, his grandfather Prince Dwarkanath, who was the first independent merchant of British India. As middlemen in a trading world the Tagore family willingly allied themselves with European merchants in banking and insurance believing that was good for their country and its future. When examining the family's history one is left without doubt that these pioneers, (or the “Calcutta Medici” as they have been described by historians), established the material foundation of a society which was at ease with high British culture, and which held their own solidly in British-Indian commerce, and all along grew in strength as cultural nationalists. With them there was an advent of new ideals, which at the same time were as old as India.

All of these formative influences of looking beyond narrow domestic walls went into the making of the Santiniketan school and Visva- Bharati international university. It was hoped that the institution's holistic values imparted through a new and alternative education would help to build a new Indian personality free from the conflict of communities and capable of appreciating the many currents of the Indian cultural tradition along with the humanistic and liberal values of the West. The new Indian personality would belong neither to the East nor to the West, but be a reconciler of both.

Tagore wrote, 'The India of modern days comprised not only the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain, whose common culture had its origin in India itself, but also the Mohammadan with his wonderful religious democracy of semitic origin and the Christian with his political democracy nurtured in Europe. There was also in India the Parsi from whom we had parted long ago outside the boundaries of India but who had come back to us again ... If Santiniketan was to become truly the guest house of India it had to be so comprehensive as to find room for each and all of these in its ripest scholarship. The treasures which these different religious cultures contained should be brought into practical use in relation to the modern world, not held apart and miserly hoarded'. Tagore gave an important place in Visva-Bharati's research agenda to studying also the life-histories of the medieval sages of India such as Kabir, Nanak, Dadu, Ruidas and others who broke through barriers of social and religious exclusiveness and brought together India's different communities on the genuine basis of spiritual idealism. He honoured them as the 'people's saints'. They swept the country with a progressive movement by their spontaneous message – 'he alone knows Truth who knows the unity of all beings'.

A poem from his Gitanjali, titled India's Prayer in its English translation, is a powerful statement of his hope for a future cleansed of divisive and nationalist politics. The words are,

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Where knowledge is free; Where the world has not been broken up into narrow domestic walls; Where the words come out from the depth of truth; Where tireless striving stretches its arms into perfection; Where the clear stream of reason Has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit; Where the mind is led forward By Thee into ever-widening thought and action Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, Let my country awake.

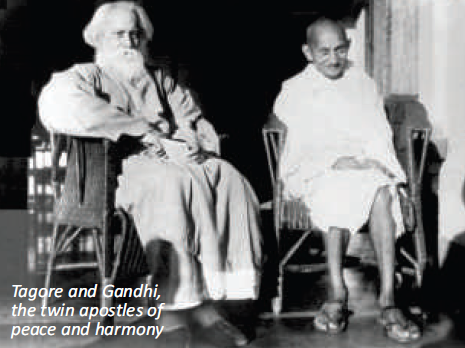

Clearly, there was a longing quest in this poem for an enlightened future for his country. Indeed, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru acknowledged his ideas for a liberal and secular democracy as crucial in shaping India's future particularly in the inter-War years. Yet, for most of the past century, while Tagore was celebrated, his cosmopolitan educational project in Santiniketan was ignored and marginalized by the imperatives of a competitive capitalism and nationalism. There are several areas where I believe Tagore was limited by both the historical forces of his time and his own particular approach. But that cannot diminish the relevance of his vision for the future and some of his strategies for our own time. From the point of view of contemporary global history too, which numerous scholars across the disciplines of political and social sciences have rightly perceived as having entered a new cycle of imperialism, Tagore's ideals offer much scope for important reappraisal. In some ways this is happening in his 150th year when many of the symposia being held in his memory are addressing his ideas and addressing and raising the question of their global relevance today. These symposia are taking place in India and in the Western countries. Unesco is currently preparing a document titled “A Reconciled Universal” by drawing from the works of Tagore, Neruda and Césaire -- Three Humanist Poets of the South in the words of Unesco's Project -- by projecting their individual messages beyond their particular significance and striking a chord more deeply together than singly in building a humanist platform, for an alliance between civilizations, to counter the heightened pressure of economic, political, social, environmental, religious and cultural ruptures and tensions of today.

Finally, let us ask ourselves: today we have roads, four way roads, quadrilaterals, flyovers, bypasses. But bridges? We lack those. We lack the hand that will say 'hullo, what is all this?' Surely, something is wrong. Something is missing. We see but do not notice. We hear but do not listen. We have lost the human touch in the embrace of systems, lost the human face in the gallery of assembly line digits. We plan, but do we feel?

Tagore had a vision for the future, and did what he could for it singlehandedly, because he felt strongly. Perhaps that could be his legacy at least in our personal lives as we honour him in his 150th year. I sense that the organizers of this Tagore Festival have felt a commitment to his legacy in this effort to re-visit Tagore's ideals and the creative unity of his cultural gifts to humanity, and thus to enrich the communities in this large and vibrant city of Los Angeles. I am very grateful to have been able to participate in this effort.