Right to privacy: India

(→Supreme Court’s judgements) |

(→1975 Govind vs MP (is an FR); 1976: ADM Jabalpur) |

||

| Line 445: | Line 445: | ||

Later, in 1976, the SC, in ADM Jabalpur case, succumbed to the powers that be and gave a blot of a ruling that all rights, including right to life, remained suspended during Emergency . It virtually accepted then attorney general Niren De's constitutionally flawed argument that during Emergency , even if a triggerhappy policeman shot a citizen, there was no constitutional remedy available to the victim's kin. | Later, in 1976, the SC, in ADM Jabalpur case, succumbed to the powers that be and gave a blot of a ruling that all rights, including right to life, remained suspended during Emergency . It virtually accepted then attorney general Niren De's constitutionally flawed argument that during Emergency , even if a triggerhappy policeman shot a citizen, there was no constitutional remedy available to the victim's kin. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Not a fundamental right; not an absolute entitlement: SC, 2017== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Right-to-privacy-not-absolute-state-can-place-20072017001039 Dhananjay Mahapatra & Amit Anand Choudhary|Right to privacy not absolute, state can place limits, says SC|Jul 20 2017 : The Times of India (Delhi)] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Supreme Court on Wednesday expressed strong reservations about declaring right to privacy a fundamental right, and said privacy could never be an absolute entitlement with the state having no power to restrict it. | ||

| + | “You all are arguing as if right to privacy should be declared as an absolute right.What should be its width and contour? What should be the reasonable restrictions attached to it? Right to privacy cannot be so absolute and overar ching that the state is prohibited from legislating restrictions on it,“ a nine-judge bench told petitioners who argued for privacy to be treated as fundamental right. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The remarks came on the opening day of the hearing by the CJI J S Khehar-led bench to settle the question of whether right to privacy , which is not guaranteed under the Constitution, can be included among the fundamental rights. The judicial exploraition of whether the right to privacy can be a fundamental right saw a nine-judge SC bench directing a whole set of searching questions at the lawyers representing petitioners. Senior advocate Gopal Subramanium said privacy was embedded in all forms of liberty , which stood at the core of an individual's fundamental rights. He drew support from former attorney general Soli J Sorabjee, who said even though right to privacy did not find mention in the Constitution, it continued to be an “inalienable right“ inherent in every human being. “Right to privacy can be deduced from other fundamental rights as was done by the SC while terming freedom of press as part and parcel of right to freedom of speech and expression despite freedom of press not finding mention in the Constitution,“ Sorabjee said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Questioning counsel's attempt to link privacy to liberty , the bench said, “Every element of liberty is not privacy . Like right to dissent is part of liberty but it is not right to privacy . If we declare right to privacy as a fundamental right, will it permit the government to enact a law prohibiting social media from making personal details of its users public? So, what will be the obligations of a state in such a situation?“ The enormity of crystallising a concept which has remained amorphous and can mean different things to different people became immediately obvious, putting paid to the CJI's ambitious objective of wrapping up the hearing within a day. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The bench comprising CJI Khehar and Justices J Chelameswar, S A Bobde, R KAgrawal, R F Nariman, A M Sapre, D Y Chandrachud, Sanjay K Kaul and S Abdul Nazeer will continue the hearing on Wednesday as the Centre is yet to put forward its arguments. | ||

| + | [[File:righ.png||frame|500px]] | ||

| + | Chelameswar, Bobde, Nariman and Chandrachud took the lead in outlining the bench's concerns and fired a volley of questions. “There is an amorphous right called right to privacy . If we can't define what is right to privacy and what are its limitations, can we just leave it with a declaration that it is a fundamental right? We do not know what proportions social media will attain in the next five years and the issues of privacy it would throw up. We can understand privacy in the context of cohabitation with wife, sexual orientation but can right of privacy be so broad that parents can decide whether or not to send their children to school? | ||

| + | Should we attempt giving a broad definition to it?“ | ||

Revision as of 12:58, 30 September 2017

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents

|

The legal position

See graphic, ' The court cases that led to the SC taking up the issue of the right to privacy'

Not every aspect of privacy is fundamental right: SC

From The Times of India, August 25, 2017

See graphic, 'Seven cases in the Supreme Court that upheld the right to privacy'

Chief Justice Khehar sums up Centre’s arguments as also saying that not every aspect of privacy is a fundamental right and it “depends on a case-by-case basis.”

The Centre told the Supreme Court that privacy was indeed a fundamental right, but a “wholly qualified” one.

This led a nine-judge Constitution Bench headed by Chief Justice of India J.S. Khehar on Wednesday to sum up Attorney General K.K. Venugopal’s submission thus: “You are saying that right to privacy is a fundamental right. But not every aspect of it [privacy] is a fundamental right. It depends on a case-to-case basis.”

Mr. Venugopal agreed to the court’s interpretation of the government stand on privacy.

Earlier the court kept prodding Mr. Venugopal to make the government’s position clear. At one point, Chief Justice Khehar even said that the reference to the nine-judge Bench could be closed if the Centre agreed that privacy was a fundamental freedom.

“Petitioners had argued that there is a fundamental right to privacy. You [Centre] had stalled them by saying that privacy is not a fundamental right. You quoted our eight and six judges’ Benches’ judgments to claim privacy is not a fundamental right. So, the five-judge Bench hearing the Aadhaar petitions referred the question ‘whether privacy is a fundamental right or not’ to us. Now if you are saying that privacy is a fundamental right, shall we close this reference right now itself?” Chief Justice Khehar asked Mr. Venugopal.

The Attorney General explained to the Bench that the government did not consider privacy to be a single, homogenous right but rather a “sub-species of the fundamental right to personal liberty and consists of diverse aspects. Not every aspect of privacy is a fundamental right.” Some aspects of privacy were expressly defined in the Constitution, while some were not.

Mr. Venugopal said there was a “fundamental right to privacy. But this right is a wholly qualified right.”

He submitted that citizens could not agitate against Aadhaar, saying it was a violation of their right to privacy. And as far as Aadhaar was concerned, privacy was not a fundamental and absolute right. The state could subject privacy to reasonable restrictions in order to preserve the right to life of the masses. He said an elite few could not claim that their bodily integrity would be violated by a scheme which served to bring home basic human rights and social justice to millions of poor households across the country.

At this, Justice Rohinton Fali Nariman retorted: “But Mr. Venugopal, don’t forget the little man’s right to privacy, everything about right to privacy is not connected to the Aadhaar issue.”

To this, Mr. Venugopal argued that privacy was submissive to the fundamental right to life under Article 21. Aadhaar was a measure by the state to ensure the teeming millions of poor in the country were not reduced to lead an “animal existence.”

“Petitioners have divided privacy into the realms of the body and mind. They say the three aspects of privacy include bodily integrity, dissemination of personal information and the right to make own choices. Tell us which among these aspects do not fit the Bill under Article 21 [right to life],” Justice Nariman asked.

"You are wrong to say that privacy is an elitist construct. Privacy also affects the masses. For example, there is an increase in instances of cervical cancer among women in impoverished families. Right to privacy of these women will be the only right standing in the way of State subjecting them to a ‘health trial’ or, say, compulsory sterilisation," Justice D.Y. Chandrachud pitched in.

As an aside, Justice Chandrachud suggested a middle way in the Aadhaar conundrum, saying personal data could be handed over to the state, provided it collected the personal information under a statutory law; had facilities to keep them secure; and used the data only for a legitimate purpose.

But Chief Justice Khehar intervened, saying “we [the nine judges] are here to decide whether there is at all a fundamental right to privacy... The question whether Aadhaar violates privacy will be decided later by the five judges. So now you [Centre] have said privacy is a fundamental right,” the Chief Justice told Mr. Venugopal.

At this, Additional Solicitor General Tushar Mehta intervened for some of the States, saying he wanted to argue that “privacy is a right but not a fundamental right.”

“But he [Mr. Venugopal] has already said that privacy is a fundamental right,” Chief Justice Khehar responded to Mr. Mehta.

Challenging aspects of Aadhaar

The Times of India, Aug 21 2017

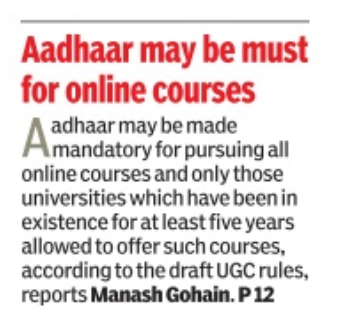

A nine-judge Constitution bench is set to give its judgment on whether a fundamental right to privacy exists under the Constitution.The verdict will remain authoritative for decades, defining the relationship between citizens and the state in the digital era. It will rightaway impact the outcome of about 24 cases where various aspects of Aadhaar have been challenged, petitioners arguing that the scheme and making it mandatory violates fundamental rights to privacy and equality.Here, a lowdown ahead of the privacy hearing

Will the nine-judge bench decide on Aadhaar?

The bench will decide whether a fundamental right to privacy exists under the Indian Constitution. This bench will not decide the fate of Aadhaar, only the nature and status of the right to privacy under the Constitution.

The SC ruling will, however, be extremely important in deciding the fate of Aadhaar and will impact all public and private services with which Aadhaar is linked, from requesting an ambulance to opening a bank account. It will have far-reaching ramifications in this digital age: how much can the state know about us, and what it can do with that knowledge? The right to privacy impacts many more issues than just Aadhaar and will allow claims in the context of beef ban laws, prohi bition, women's reproductive rights as well.

What are the arguments on either side?

The petitioners say that the SC has recognised the fundamental right to privacy in an unbroken chain of judgments. They say privacy is associated with and is the bulwark of other rights. There can be no dignity without privacy , and dignity is part of the Preamble, which is part of the Constitution's basic structure. Privacy is located in the golden trinity of Articles trinity of Articles 14, 19, and 21. They argue that the Constitution is a living document. Its interpretation must be in accord with passage of time and developments in law. They say India has international obligations to recognise a fundamental right to privacy.

The respondents say that privacy is a vague concept, and vague concepts cannot be made fundamental rights. Some aspects of privacy are covered by Article 21 and its other aspects should be regulated by laws only , not separately as a fundamental right.Right to life of others is more important than right to privacy .If right to privacy impedes Aadhaar, then it would deprive millions of food and shelter. They argue framers intentionally did not include privacy in fun damental rights section.

Without linking Aadhaar, will government schemes be impacted?

There is conflicting data.A 2012 study by National Institute of Public Finance and Policy estimated that linking Aadhaar could save a tenth of money spent on PDS and MGNREGS schemes. But the study was criticised for using outdated data on leakages, and overestimating the number of ghost beneficiaries.

It is also unclear how much of the `savings' from linking Aadhaar to schemes is because genuine beneficiaries are now excluded. In a study of Hyderabad PDS outlets linked to Aadhaar, nearly 10% of households reported technical problems with Aadhaar due to which they did not receive rations.The Economic Survey 201516 claimed that linking Aadhaar to LPG subsidies had saved the government 25%. But the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) estimated that 92% of this `saving' was due to the fall in global oil prices.

Apart from these uncertain savings, rollout of government schemes would continue as earlier without Aadhaar, since Aadhaar is meant to help existing schemes. In fact, there have been reports that rollout of Aadhaar-based systems is posing some problems. Fingerprint authentication often does not work if labourers' hands are callused; the elderly and disabled have trouble accessing affordable transport go to government centres, instead of sending others as they did earlier; technical problems abound with uneven quality of connections and devices.

Is the demand for citizen data the issue, or the security of the data?

Both. Creating one database of all details for an all-purpose ID (Aadhaar) creates its own problems -the spectre of surveillance, the possibility of exclusion from all government services, among others. On the security front, several experts believe that for centralised databases, “the question is not whether it can be hacked, but when.“

The SC verdict, 2017

See graphic, 'What the SC judgement on the right to privacy said, August 2017'

See graphic, 'Issue that the right to privacy ruling, 2017, can impact'

HIGHLIGHTS

The order affects all 134 crore Indians

The apex court overruled previous judgments on the privacy issue

It overruled an eight-judge bench judgment in the MP Sharma case and a six-judge bench judgment in Kharak Singh case

NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court (SC) ruled that privacy is a fundamental right because it is intrinsic to the right to life.

"Right to Privacy is an integral part of Right to Life and Personal Liberty guaranteed in Article 21 of the Constitution," the SC's nine-judge bench+ ruled unanimously. It added that the right to privacy is intrinsic to the entire fundamental rights chapter of the Constitution.

This judgement is a blow to Aadhaar as the Centre now has to convince SC that forcing citizens to give a sample of their fingerprints and their iris scan does not violate privacy. The SC bench's judgment will touch the lives of 134 crore Indians. It was not meant to decide on the fate of Aadhaar, just on whether privacy of an individual was a part of their inviolable fundamental rights. What this means is a five-judge bench of the SC will test the validity of Aadhaar on the touchstone of privacy as a fundamental right.

The apex court's nine-judge bench overruled previous judgments on the issue- an eight-judge bench judgment in the MP Sharma case and a six-judge bench judgment in Kharak Singh case, both of which had ruled that privacy is not a fundamental right+ . The bench comprised Justices Khehar, J Chelameswar, S A Bobde, R K Agrawal, R F Nariman, A M Sapre, D Y Chandrachud, Sanjay K Kaul and S Abdul Nazeer.

Attorney general K K Venugopal, who had argued that right to privacy cannot be a fundamental right, welcomed the SC decision. "Whatever the 9-judge bench says is the correct law," said Venugopal to TOI.

The question about the constitutional status of right to privacy arose in a bunch of petitions, led by retired HC judge KS Puttaswamy, which in 2012, challenged the UPA government's decision to introduce the biometric data-enabled Aadhaar ID for citizens. The petitioners included first Chairperson of National Commission for Protection of Child Rights and Magsaysay awardee Shanta Sinha, feminist researcher Kalyani Sen Menon, and others.

This question was referred to a five-judge Constitution bench on August 11, 2015.

The five-judge bench, led by Chief Justice JS Khehar, met on July 18 to decide the issue, but was told by the Centre that the strength of the bench was inadequate as an eight-judge bench in the MP Sharma case in 1954, and a six-judge bench in the Kharak Singh case in 1962, had ruled that right to privacy was not a fundamental right. The bench was quick to refer the matter to a nine-judge bench, which began hearing arguments from July 19, and concluded hearing on August 2, after a lively debate involving renowned lawyers to greenhorns.

The Centre, through attorney general KK Venugopal, argued against privacy being an inviolable fundamental right+ . This argument presented to the bench the constitutional complications intrinsic to privacy when its width and play is examined through the crosswires of fundamental rights.

"Privacy, even if assumed to be a fundamental right, consists of a large number of sub-species... It will be constitutionally impermissible to declare each and every instance of privacy a fundamental right. Privacy has varied connotations when examined from different aspects of liberties. If the SC wants to declare it a fundamental right, then it probably has to determine separately the various aspects of privacy and the extent of violation that could trigger a constitutional remedy," Venugopal said.

Meanwhile, the petitioners contended that the right to privacy was "inalienable" and "inherent" to the most important fundamental right which is the right to liberty. They said that right to liberty, which also included the right to privacy, was a pre-existing "natural right" which the Constitution acknowledged and guaranteed to the citizens in case of infringement by the state.

1976, emergency-era judgment suspending right to life overruled

It required an exceptionally courageous decision to erase a historical blunder -the 1976 Emergency-era judgment upholding the government's decision to suspend right to life -which had remained a blot in the shining 67-year run of the Supreme Court.

When a nine-judge SC bench did that on Thursday through Justice D Y Chandrachud's lead judgment, the main author was carrying out the unenviable task of overruling his father Justice Y V Chandrachud, who was part of the majority judgment which had endorsed the Indira Gandhi government's decision to suspend right to life during Emergency.

The majority judgment of the 1976 verdict was written by Justice M H Beg with whom then CJI A N Ray and Justices Chandrachud and P N Bhagwati had agreed.Justice H R Khanna had strongly dissented, stressing the inviolability of right to life.

Driven passionately to correct a constitutional blunder to which his father was a party 41 years ago, son Chandrachud displayed steely resolve to tread the constitutional path and declare, “The judgments rendered by all the four judges constituting the majority in ADM Jabalpur are seriously flawed... ADM Jabalpur must be and is accordingly overruled.

“Justice Khanna was clearly right in holding that the recognition of right to life and personal liberty under the Constitution does not denude the existence of that right, apart from it nor can there be a fatuous assumption that in adopting the Constitution, the people of India surrendered the most precious aspect of the human persona, namely, life, liberty and freedom to the state on whose mercy these rights would depend.

On the quality and value of A D M Jabalpur judgment, Justice Chandrachud said, “When histories of nations are written and critiqued, there are judicial decisions at the forefront of liberty. Yet others have to be consigned to the archives, reflective of what was, but should never have been.“

SC Overturns 63-Yr-Old Verdict

Privacy is a postulate of human dignity itself: Chandrachud, August 25, 2017: The Times of India

9-Judge Bench Unanimously Declares Privacy A Fundamental Right, Says It's Intrinsic To Right To Life & Personal Liberty

Court Overturns 63-Yr-Old Verdict

Propelling India into the ranks of progressive societies that ensure privacy of their citizens, a nine-judge Supreme Court bench unanimously ruled on Thursday that privacy is a fundamental right, protected as an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty and as part of the freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution.

In a historic judgment, the bench headed by CJI J S Khehar -which included Justices J Chelameswar, S A Bobde, R K Agrawal, R F Nariman, A M Sapre, D Y Chandrachud, Sanjay K Kaul and S Abdul Nazeer -upturned a 63-year-old ruling of an eight-judge bench that had refused to recognise privacy as a fundamental right. The 547-page ruling set up many landmarks to outline what constitutes a dignified life and the obligation of the state to help its citizens lead one.

It emphasised the value of dissent and tolerance, besides the rights of minorities, including sexual minorities, clearing the way for the possible voiding of the SC's controversial order to reverse the decriminalisation of consensual gay sex by the Delhi high court. It also boldly delineated the limits to the state's intervention in the lives of citizens.

However, the bench was alive to the challenges thrown up by technology and recognised that a balance needs to be maintained between the right to privacy and the right of the state to impose reasonable restrictions on it for legitimate aims such as national security , prevention and investigation of crimes and distribution of welfare resources.

What stood out was privacy being declared intrinsic to right to life and that it formed part of the sacrosanct chapter on fundamental rights in the Constitution, which has been regarded since 1973 as part of the basic structure, immune from Parliament's interference. The unanimo us verdict was, “Right to privacy is protected as an intrinsic part of right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 and as part of the freedoms guaranteed by Part III.“

The bench added, “Like the right to life and liberty , privacy is not absolute. The limitations which operate on the right to life and personal liberty would operate on the right to privacy . Any curtailment or deprivation of that right would have to take place under a regime of law. The procedure established by law must be fair, just and reaso nable. The law which provides for the curtailment of the right must also be subject to constitutional safeguards.“

With this ruling, the constitution bench set the stage for a three-judge bench to decide the validity of Aadhaar, challenged by 21petitions led by retired HC judge K S Puttaswamy , by scrutinising whether collection of biometric data and linking it with various activities of citizens violated their right to privacy.

But equally significant were two ingrained sub-rulings -one, it said a two-judge SC bench in 2014 had wrongly curtailed the sexual preferences of the LGBT community and, two, it attempted to erase the Emergency-era judgment in the ADM Jabalpur case by overruling its logic that the government could suspend right to life in critical situations.

It was Justice Chandrachud's 265-page illustrative, analytical and incisive judgment that formed the core of the nine-judge bench's decision. Justice Chandrachud wrote the judgment for himself and for Justices Khehar, Agrawal and Nazeer. The other judges -Justices Chelameswar, Bobde, Nariman, Sapre and Kaul -agreed through separate judgments.

Referring to as many as 300 judgments from India and abroad, Justice Chandrachud demolished the Centre's argument that privacy was a common law right that was a subspecies of many rights, and hence, incapable of being termed as a standalone homogeneous fundamental right.

“Once privacy is held to be an incident of the protection of life, personal liberty and of the liberties guaranteed by the provisions of Part III of the Constitution, the submission that privacy is only a right at common law misses the wood for the trees,“ he said.

Defining the nature and character of privacy , he said, “Privacy postulates the reservation of a private space for the individual, described as the right to be let alone.The concept is founded on the autonomy of the individual.The ability of an individual to make choices lies at the core of the human personality.“ Elaborating on the con cept and attempting to define the limitless footprints of privacy in an individual's activities, Justice Chandrachud said, “The body and the mind are inseparable elements of the human personality . The integrity of the body and the sanctity of the mind can exist on the foundation that each indi vidual possesses an inalienable ability and right to preserve a private space in which the human personality can develop. Without the ability to make choices, the inviolability of the personality would be in doubt. Recognising a zone of privacy is but an acknowledgement that each individual must be entitled to chart and pursue the course of development of personality . Hence, privacy is a postulate of human dignity itself.“

“Dignity cannot exist without privacy. Both reside within the inalienable values of life, liberty and freedom which the Constitution has recognised. Privacy is the ultimate expression of the sanctity of the individual. It is a constitutional value which straddles across the spectrum of fundamental rights and protects for the in dividual a zone of choice and self-determination,“ the judgment said.

“The ability of the individual to protect a zone of privacy enables the realisation of the full value of life and liberty. Liberty has a broader meaning of which privacy is a subset. All liberties may not be exercised in privacy . Yet others can be fulfilled only within a private space. Privacy enables the individual to retain the autonomy of the body and mind. The autonomy of the individual is the ability to make decisions on vital matters of concern to life,“ the verdict said.

Justice Chandrachud wrote the judgment for himself and for Justices Khehar, Agrawal and Nazeer. The other judges -Justices Chelameswar, Bobde, Nariman, Sapre and Kaul -agreed through separate judgments.

Reaction to the judgement

SC's verdict on privacy: Who said what, Aug 24, 2017: The Times of India

The Supreme Court in a landmark judgment, declared that right to privacy was a Fundamental right under the Constitution. Here is how politicians, activists and social media influencers reacted on the apex court's remarkable order:

Rahul Gandhi

Congress vice president Rahul Gandhi termed the SC's verdict as "a victory for every Indian".

Arvind Kejriwal

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal thanked the Supreme Court for this important judgement.

Mamata Banerjee

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee also welcomed the apex court's judgement on privacy.

P Chidambaram

Senior Congress leader P Chidambaram while welcoming the SC's decision said,"The Aadhar we conceived was perfectly compatible with the Right To Privacy.It is the interpretation of this government of the Article 21 which is an invasion of Right To Privacy." He also said that "there is no fault in the Aadhar concept but there is fault in how this government plans to use or misuse Aadhar as a tool."

Jyotiraditya Scindia

Senior Congress leader and Member Parliament from Madhya Pradesh Jyotiraditya Scindia welcomed Supreme Court's unanimous verdict.

Subramanian Swamy

Senior BJP leader Subramanian Swamy pinned his hope on modification of Aadhaar.

Omar Abdullah

After SC's verdict, former Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah expressed his happiness that he now has right to privacy.

Rajeev Chandrasekhar

BJP MP Rajeev Chandrasekhar was glad over the SC's verdict.

Randeep S Surjewala

Congress spokesperson Randeep S Surjewala said that the SC's verdict is a decisive defeat for BJP Government.

Kamal Haasan

SC upholds the right to privacy Nothing vague or amorphous about it. People thank the Honourable Judges. These are moments that make India.

Impact on Aadhaar

Remarkable change of stance

Menaka Guruswamy, August 25, 2017: The Times of India

The privacy verdict signi fies a remarkable shift in the self-imagination of the Supreme Court from a reticent post-colonial liberty court to an erudite constitutional court for a modern democracy .While the Constitution's right to life and personal liberty was expanded to protect socio-economic rights like health, livelihood and education, it was correspondingly fragile on personal liberty -a classical civil right. The privacy verdict is remarkable because it's a shift away from the apex court that's deferred to the State when it overpowers private citizens' `right to be left alone'.

The writer practices law in SC and is visiting faculty at Columbia Law School

SC: Data storage is permissible to check leak of resources

The landmark ruling giving right to privacy the status of a fundamental right may not serve as a dampener for Aadhaar-based schemes as the Supreme Court listed the need, apart from security concerns, to prevent pilferage of scarce public resources as among grounds on which the government would be justified in collecting and storing data.

If, on the one hand, the SC rejected the Centre's argument that privacy could not be treated as a fundamental right to scuttle the right of impoverished millions to access food through Aadhaarlinked welfare schemes, on the other hand, it unhesitatingly conceded the need for collection of personal data by the government to ensure essential items reach the needy .

The Centre has cited diversion of subsidies for the poor as the chief defence for storage of personal data of citizens on the Aadhaar platform.

Justice D Y Chandrachud, writing the main judgment, said: “In a social welfare state, the government embarks upon programmes which provide benefits to impoverished and marginalised sections of society . There is a vital state interest in ensuring that scarce public resources are not dissipated by the diversion of resources to persons who do not qualify as recipients.“

He added: “Allocation of resources for human development is coupled with a legitimate concern that the utilisation of resources should not be siphoned away for extraneous purposes. Data mining with the object of ensuring that resources are properly deployed to legitimate beneficiaries is a valid ground for the state to insist on the collection of authentic data.“

However, he said the data collected by the state had to be utilised for legitimate purposes and not in an unauthorised manner for extraneous purposes. “This will ensure that the legitimate concerns of the state are duly safeguarded while, at the same time, protecting privacy concerns,“ he said.

“Prevention and investigation of crime and protection of revenue are among the legitimate aims of the state.Digital platforms are a vital tool of ensuring good governance in a social welfare state.Information technology , legitimately deployed, is a powerful enabler in the spread of innovation and knowledge,“ he said. This is in sync with the Modi government's publicly declared policy in making Aadhaar mandatory .

But the final outcome of the petitions challenging the validity of Aadhaar will depend on the manner a threejudge bench construes right to privacy, the newly-declared fundamental right, while scrutinising the alleged privacy invasive element of biometric data-enabled Aadhaar.

Justice Chandrachud said: “Both anonymity and privacy prevent others from gaining access to pieces of personal information yet they do so in opposite ways.Privacy involves hiding information whereas anonymity involves hiding what makes it personal. An unauthorised parting of the medical records of an individual which have been furnished to a hospital will amount to an invasion of privacy .

“On the other hand, the state may assert a legitimate interest in analysing data borne from hospital records to understand and deal with a public health epidemic such as malaria or dengue to obviate a serious impact on the population. If the state preserves the anonymity of the individual it could legitimately assert a valid state interest in the preservation of public health to design appropriate policy interventions on the basis of the data available to it.“

UID: Right To Privacy Subject To Restrictions

Says Right To Privacy Subject To Restrictions

There is sufficient leeway for the government to pursue digitalisation programmes, many of which are centred around Aadhaar, with the Supreme Court setting out “legitimate state aims“ that can allow linkage of UID with social welfare schemes.

The SC's clear cut reference to national security , prevention and investigation of crime, encouraging innovation and making delivery of welfare programmes' more efficient as permissible objectives will help preserve Aadhaar-driven programmes that have been challenged over privacy issues.

While the petitioners had sought the establishment of privacy as a fundamental right by itself the court has located it within the right to life and liberty and therefore subject to restrictions that apply to Article 21.This would mean initiatives like linking Aadhaar to tax returns can be justified on the grounds that this will help check fraud through use of multiple PAN cards commonly used to duck tax.

The judgement provides grounds for the government to argue that the use of Aadhaar, and the consequent implications for privacy , need to be weighed against whether UID has improved governance. So if the government can show duplicate and ghost beneficiaries have been eliminated, graft reduced and right beneficiaries benefited, it will have a strong case for use of biometric verification.

Data protection is the other crucial issue as the SC expressed concern during arguments that it did not want information to leak and users harassed by telemarketers. Here UID's own security systems -dispersal of servers and protocols requiring several staff to share codes before accessing internally -are as important as guidelines for government and private users of KYC services.

The SC judgement does make it evident that the government will have to present a robust reasoning for expansion for Aadhaar use to more areas apart from delivery of government services. But the court itself has asked for Aadhaar linkage to mobile telephone connections and its use for verification of identities does not seem likely to be affected.

The international references to use of biometrics include maintainence of DNA profiles of convicts in some countries like the US where the facility has helped law agencies resolve unsolved crimes while also, on occasion, establishing a wrongly convicted person as innocent. The expansion of privacy into a fundamental right, however, means the provisions of the Aadhaar Act not to allow collation of data on individuals will be taken more seriously by the current and succeeding governments. On the other hand, the ruling that there is no general right to privacy means government action will continue.

The writer is a senior Supreme Court advocate

Implications go beyond Aadhaar

Alok Prasanna Kumar, August 25, 2017: The Times of India

The implications of this judgment go beyond Aadhaar. It does not necessarily mean that legislations will be struck down for being unconstitutional as that depends on the circumstances in each case and the justifications offered. Nonetheless, those arguing against laws like the ban on beef and alcohol consumption have been given a new and powerful ground to challenge intrusive laws.

The writer is senior fellow at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy

Impact on government

’State interest’ loophole remains

Chinmayi Arun, August 25, 2017: The Times of India

The judgment comes with a barb in its tail -the Supreme Court has carved out a potential loophole through which the state can violate the right to privacy after all. It has held that privacy may be violated when there is a legitimate state interest. The majority judgment has cited web-monitoring for thwarting cyber attacks and terrorists, and social welfare programmes as potential situations in which the state might violate the right to privacy .

This means that like the phone-tapping judgment, the privacy judgment has not done enough to curtail state surveillance. But it must be commended for protecting the dignity and privacy of the individual in the context of sexuality and personal space.

The writer is executive director, Centre for Communication Governance and faculty associate of the Berkman Center, Harvard University

State intrusion into certain aspects of human life

The Times of India, Aug 26 2017

In his separate but concurrent judgment on right to privacy, Justice J Chelameswar said the state should not have “unqualified authority“ to intrude into certain aspects of human life which amounts to violation of right to privacy.

“I do not think that anybody in this country would like to have the officers of the state intruding into their homes or private property at will or soldiers quartered in their houses without their consent. I do not think that anybody would like to be told by the state as to what they should eat or how they should dress or whom they should be associated with either in their personal, social or political life,“ he said.

“Freedom of social and political association is guaranteed to citizens under Article 19(1)(c). Personal association is still a doubtful area. The decision making process regarding the freedom of association, freedoms of travel and residence are purely private and fall within the realm of the right of privacy. It is one of the most intimate decisions,“ he said.

“All liberal democracies believe that the state should not have unqualified authority to intrude into certain aspects of human life and that the authority should be limited by parameters constitutionally fixed. Fundamental rights are the only constitutional firewall to prevent state's interference with those core freedoms constituting liberty of a human being. The right to privacy is certainly one of the core freedoms which is to be defended.It is part of liberty within the meaning of that expression in Article 21,“ he said.

Religious and ancient texts also favour right to privacy: Justice Bobde

Referring to religious and ancient books, Justice S A Bobde said people's right to privacy was recognised from time immemorial and every individual was entitled to perform his actions in private without being observed or spied upon.

Quoting Ramayana, Bible, Hadith, Arthashastra and Grihya Sutras, Justice Bobde said right to privacy had been prescribed as an inalienable right in all religions.

“Not recognising character of privacy as a fundamental right is likely to erode the very sub-stratum of personal liberty guaranteed by the Constitution.The decided cases clearly demonstrate that particular fundamental rights could not have been exercised without the recognition of right of privacy as a fundamental right. Any de-recognition or diminution in the importance of right of privacy will weaken fundamental rights which have been expressly conferred,“ he said.

“Even in the ancient and religious texts of India, a well-developed sense of privacy is evident. A woman ought not to be seen by a male stranger seems to be a wellestablished rule in the Ramayana. Grihya Sutras prescribe the manner in which one ought to build one's house in order to protect the privacy of its inmates and preserve its sanctity during the performance of religious rites, or when studying the Vedas or taking meals. The Arthashastra prohibits entry into another's house, without the owner's consent. Similarly in Islam, peeping into others' houses is strictly prohibited.The Hadith makes it reprehensible to read correspondence between others. In Christianity, we find the aspiration to live without interfering in the affairs of others in the text of the Bible,“ he said.

Right to privacy is not an elitist concept: Justice Nariman

Justice R F Nariman rejected the Centre's submission that right to privacy was an “elitist construct“ which could not be declared a fundamental right in a poor country where people were denied basic amenities of life.

“The attorney general argued that between the right to life and the right to personal liberty, the former has primacy and any claim to privacy which would destroy or erode this basic foundational right can never be elevated to the status of a fundamental right. Elaborating further, he stated that in a developing country where millions of people are denied the basic necessities of life and do not even have shelter, food, clothing or jobs, no claim to a right to privacy as a fundamental right would lie. First and foremost, we do not find any conflict between the right to life and the right to personal liberty,“ Justice Nariman said.

“Both rights are natural and inalienable rights of every human being and are required in order to develop hisher personality to the fullest. Indeed, the right to life and the right to personal liberty go handin-hand, with the right to personal liberty being an extension of the right to life. A large number of poor people that (K K ) Venugopal talks about are persons who in today's completely different and changed world have cell phones, and would come forward to press the fundamental right of privacy, both against the government and against other private individuals. We see no antipathy whatsoever between the rich and the poor in this context,“ he said.

Unity & integrity of nation can't survive unless dignity of citizen is guaranteed: Justice Sapre

Justice Abhay Manohar Sapre said right to privacy was essentially a natural right, which every human inhered by birth and it could not be denied.

Justice Sapre said, “In my view, unity and integrity of the nation cannot survive unless the dignity of every individual citizen is guaranteed. It is inconceivable to think of unity and integration without the assurance to an individual to preserve his dignity. In other words, regard and respect by every individual for the dignity of the other one brings the unity and integrity of the nation.

“In my considered opinion, right to privacy of any individual is essentially a natural right, which inheres in every human being by birth. Such right remains with the human being till he she breathes last. It is indeed inseparable and inalienable from human being. In other words, it is born with the human being and extinguish with human being.

“One cannot conceive an individual enjoying meaningful life with dignity without such right. Indeed, it is one of those cherished rights, which every civilised society governed by rule of law always recognises in every human being and is under obligation to recognise such rights in order to maintain and preserve the dignity of an individual regardless of gender, race, religion, caste and creed.“

He, however, said right to privacy was not an absolute right but was subject to reasonable restrictions, which the state was entitled to impose on the basis of social, moral and compelling public interest in accordance with law.

Clear lines drawn that govt can't overstep

Shyam Divan, August 25, 2017: The Times of India

Unlike the triple talaq de cision that had immedi ate practical impact, this verdict does not have a clear liberating takeaway , but it secures a certain space for all Indian citizens. Many passages argue for balance as well. It agrees that privacy is not an absolute value, and that the state still has the right to use new technologies. But it has drawn clear lines that government cannot overstep.

It also overturned ADM Jabalpur, one of the biggest blots on Indian jurisprudence.The contention that the right to move court to enforce the personal liberty under Art. 21 can be overruled, as happened during the Emergency , has been expressly overruled. On Aadhaar, the hard battle will remain. How can the Indian state barter health benefits for a citizen's fingerprints?

Hopefully , this judgement will get people thinking harder about such transactions.

Impact on Sec. 377 of the IPC

See graphic: Impact of the SC verdict in August 2017 on Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code ‘'

See graphic, ' Right to Privacy, a timeline, 2012-August 2017‘

Suggestions

SC: govt should draw up adequate data protection regime

The Supreme Court did not have difficulty in holding privacy as a fundamental right and mandated the government to draw up a robust data protection regime to shield people's private information from intrusion in today's internet era.

The bench recognised the grave danger to privacy because of the complexities thrown up by sharing of personal data and firms collating them to create meta-data for commercial exploitation.

“One of the chief concerns which the formulation of a data protection regime has to take into account is that while the web is a source of lawful activity -both personal and commercial -concerns of national security intervene since the seamless structure of the web can be exploited by terrorists to wreak havoc and destruction on civilised societies.Cyber attacks can threaten financial systems,“ it said.

In the lead judgment written by Justice D Y Chandrachud, the SC talked about the hidden danger and said: “Data mining processes together with knowledge discovery can be combined to create facts about individuals. Meta-data and the internet of things have the ability to redefine human existence in ways which are yet fully to be perceived.“

The SC said India was fast becoming the hunting ground for such data. Telecom Regulatory Authority of India's figures as on December 31, 2016 show the total number of internet subscribers at 391.50 million, reflecting an 18.04% change over the previous quarter. Total internet subscribers per 100 population stood at 30.56, urban internet subscribers were 68.86 per 100 population and rural internet subscribers were 13.08.

Justice Chandrachud said: “Apart from safeguarding privacy , data protection regimes seek to protect the autonomy of the individual.This is evident from the em phasis in the European data protection regime on the centrality of consent. Related to the issue of consent is the requirement of transparency which requires a disclosure by the data recipient of information pertaining to data transfer and use.“

He added: “Formulation of a regime for data protection is a complex exercise that needs to be undertaken by the state after a careful balancing of requirements of privacy coupled with other values which the protection of data subserves together with the legitimate concerns of the state.“

The SC said during the hearing on the right to privacy issue that the government had placed on record an Office Memorandum of July 31, 2017, by which it had constituted a panel led by Justice B N Srikrishna to make recommendations after reviewing data protection norms in the country .

“Since the government has initiated the process of reviewing the entire area of data protection, it would be appropriate to leave the matter for expert determination so that a robust regime for the protection of data is put into place.We expect that the Union government shall follow up on its decision by taking all necessary and proper steps,“ it said.

SC: non-state actors should be regulated to protect citizens’ rights

Noting that technological development had enabled social networking sites and web service provider companies to invade privacy of individuals by collecting and processing their data, the SC said non-state actors needed to be regulated to protect rights of citizens in the digital age and they should not be allowed to exercise control over people like “big brother“.

The SC said the capacity of online firms to invade homes and privacy of their users stood enhanced and asked the Centre to step in.

“We are in an information age. The information explosion has manifold advantages but also some disadvantages.The access to information, which an individual may not want to give, needs protection of privacy ,“ Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul said in his separate judgment. “Digital footprints can be analysed computationally to reveal patterns, trends, and associations. This is the age of big data... A large number of people would like to keep such search history pri vate, but it rarely remains private, and is collected, sold and analysed for purposes such as targeted advertising.“

Emphasising the need to regulate firms, Kaul said data was generated not just by active sharing of information but also passively , with every click on the `world wide web'.He said: “Uber knows our whereabouts. Facebook... knows who we are friends with. Alibaba knows our shopping habits. Airbnb knows where we are travelling to...“

He added: “George Orwell created a fictional state in `Nineteen Eighty-Four'. Today , it can be a reality . The technological development today can enable not only the state but also big corporations and private entities to be the big brother.“

Supreme Court’s judgements

1954 M P Sharma; 1962; Kharak Singh: not an FR

`1975 Govind Verdict Blindly Followed By Petitioners' The Supreme Court on Thursday stared at a legal vacuum as Maharashtra government, through senior advocate C A Sundaram, demonstrated that the 40-yearold judicially laid down foundation for privacy as a fundamental right was a misnomer. Despite two categorical judgments -one by an eightjudge bench in 1954 (M P Sharma case) and another by a sixjudge bench in 1962 (Kharak Singh case) -declaring that privacy was not a fundamental right, a three-judge bench verdict in 1975 in `Govind vs Madhya Pradesh' was widely believed to have ruled that right to privacy was a fundamental right and this assumption was blindly followed by SC benches over the last 40 years.

A nine-judge bench headed by Chief Justice J S Khehar has undertaken the task of determining the constitutional status of right to privacy , mainly to overcome the hurdle posed by the eight-judge and sixjudge benches.

Petitioners who had challenged Aadhaar on the ground that it violated right to privacy had relied on smaller bench judgments in the last 40 years to caution the apex court against changing what they called the four-decade-long judicial recognition given to right to privacy as a fundamental right. When Sundaram attempted to substantiate his argument that privacy was not a fundamental right, he faced a volley of questions from the bench, also comprising Justices J Chelameswar, S A Bobde, R K Agrawal, R F Nariman, A M Sapre, D Y Chandrachud, S K Kaul and S A Nazeer.

In reply, Sundaram attacked the fountainhead of right to privacy -the 1975 judgment which held sway for the last four decades.

Sundaram and advocate Rohini Musa read out several paragraphs from the 1975 judgment to point out that the three-judge bench had caveated the verdict with “if privacy was assumed to be a fundamental right“. He said there was no logic nor analysis to arrive even at the assumption that privacy formed part of the bouquet of fundamental rights guaranteed to every citizen by the Constitution. “Every subsequent judgment blindly followed the Govind verdict without reason or explanation as to why privacy is a fundamental right,“ he said.

As the facts came out, a sen se of disbelief swept the packed CJI's courtroom, including petitioners who had relied heavily on the Govind verdict. The discovery briefly lulled the bench's instinctive approach to question any counsel arguing against privacy's prime importance in the sphere of fundamental rights.

The bench drew Sundaram's attention to present day reality, when rapid technological advance is making individual privacy increasingly vulnerable. “Do we have a robust data protection regime to protect and secure personal information?“ it asked, indicating its willingness to look at privacy afresh without being burdened by past rulings.

“If we accept privacy as a constitutional right, it will have to be part of personal liberty and right to life guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution,“ it said.

Sundaram responded by reading from Constituent Assembly debates and said the framers of the Constitution had considered a proposal to make right to privacy a standalone fundamental right but discarded it after elaborate debate.

1975 Govind vs MP (is an FR); 1976: ADM Jabalpur

Privacy fundamental right, SC had ruled before Emergency|Jul 28 2017 : The Times of India (Delhi)

A nine-judge Supreme Court bench headed by Chief Justice J S Khehar was pleasantly surprised to find that the SC had delivered a verdict, believed for the last 40 years to be the foundation of privacy as fundamental right, in the year Emergency was proclaimed. The nine-judge bench wanted to know the date of the judgment. When senior advocate C A Sundaram said `Govind vs Madhya Pradesh' judgment, erroneously believed to be the first one to rule privacy as a fundamental right, was delivered on March 18, 1975, the bench broke into a smile.

For, Emergency was declared three months later on June 25, 1975. Justice J Chelameswar said he had pointed this out, as head of a threejudge bench, during the hearing on petitions challenging Aadhaar.

The surprise was understandable as the Emergency period, from 1975 to 1977, saw brutal abuse of fundamental rights of citizens and arrest and incarceration of political leaders without remedy . When the aggrieved moved high courts, some of them gave relief under the writ of habeas corpus.

Later, in 1976, the SC, in ADM Jabalpur case, succumbed to the powers that be and gave a blot of a ruling that all rights, including right to life, remained suspended during Emergency . It virtually accepted then attorney general Niren De's constitutionally flawed argument that during Emergency , even if a triggerhappy policeman shot a citizen, there was no constitutional remedy available to the victim's kin.

Not a fundamental right; not an absolute entitlement: SC, 2017

The Supreme Court on Wednesday expressed strong reservations about declaring right to privacy a fundamental right, and said privacy could never be an absolute entitlement with the state having no power to restrict it. “You all are arguing as if right to privacy should be declared as an absolute right.What should be its width and contour? What should be the reasonable restrictions attached to it? Right to privacy cannot be so absolute and overar ching that the state is prohibited from legislating restrictions on it,“ a nine-judge bench told petitioners who argued for privacy to be treated as fundamental right.

The remarks came on the opening day of the hearing by the CJI J S Khehar-led bench to settle the question of whether right to privacy , which is not guaranteed under the Constitution, can be included among the fundamental rights. The judicial exploraition of whether the right to privacy can be a fundamental right saw a nine-judge SC bench directing a whole set of searching questions at the lawyers representing petitioners. Senior advocate Gopal Subramanium said privacy was embedded in all forms of liberty , which stood at the core of an individual's fundamental rights. He drew support from former attorney general Soli J Sorabjee, who said even though right to privacy did not find mention in the Constitution, it continued to be an “inalienable right“ inherent in every human being. “Right to privacy can be deduced from other fundamental rights as was done by the SC while terming freedom of press as part and parcel of right to freedom of speech and expression despite freedom of press not finding mention in the Constitution,“ Sorabjee said.

Questioning counsel's attempt to link privacy to liberty , the bench said, “Every element of liberty is not privacy . Like right to dissent is part of liberty but it is not right to privacy . If we declare right to privacy as a fundamental right, will it permit the government to enact a law prohibiting social media from making personal details of its users public? So, what will be the obligations of a state in such a situation?“ The enormity of crystallising a concept which has remained amorphous and can mean different things to different people became immediately obvious, putting paid to the CJI's ambitious objective of wrapping up the hearing within a day.

The bench comprising CJI Khehar and Justices J Chelameswar, S A Bobde, R KAgrawal, R F Nariman, A M Sapre, D Y Chandrachud, Sanjay K Kaul and S Abdul Nazeer will continue the hearing on Wednesday as the Centre is yet to put forward its arguments.

Chelameswar, Bobde, Nariman and Chandrachud took the lead in outlining the bench's concerns and fired a volley of questions. “There is an amorphous right called right to privacy . If we can't define what is right to privacy and what are its limitations, can we just leave it with a declaration that it is a fundamental right? We do not know what proportions social media will attain in the next five years and the issues of privacy it would throw up. We can understand privacy in the context of cohabitation with wife, sexual orientation but can right of privacy be so broad that parents can decide whether or not to send their children to school? Should we attempt giving a broad definition to it?“