Rivers: India (issues)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The shrinking of Indian rivers

The extent of the problem

Water Available Per Person In A Year Has Reduced By Over Two-Thirds In Six Decades. And It's Getting Worse. Saving Water Is Not Enough, It's Time To Revive Our Lifelines

India has about 400 rivers. If laid end to end, their length adds up to nearly 2 lakh kilometres, enough to go around the earth five times or reach two-thirds of the way to the moon. They carry an enormous 1,869 billion cubic metres of water every year--enough to submerge the whole of India in nearly two feet of water. Embedded in history, this river network determines climate and geography , sustains 1.3 billion people and provides a mooring to their diverse cultures.

Why are rivers so important? A look at the water equation for the country will immediately show you. Imagine that 100 litres of water falls as rain over India. Some 53 litres is lost as it either evaporates directly or through plants and trees, or gets retained in soil. The remaining 47 litres flows into the rivers but only 28 litres is actually available because the rest is locked away in inaccessible places, or turns brackish. Of this 28 litres, 17 flows in the rivers and 11 ends up as rechargeable groundwater.

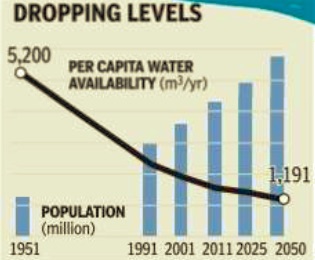

With growing population and its demands, this already insufficient water is becoming scarcer. In 1951, 5,200 cubic metres of water was available per person every year.This had dropped over two-thirds to just 1,545 cubic metres in 2011 and is projected to decline to 1,191 cubic metres by 2050.

So, rivers are becoming more and more important. Groundwater has its limits which are already being breached in many areas. Rainfall is becoming more erratic with climate change. Rivers remain a reliable source of life-giving water.

Yet, by all counts, India's fabled rivers are under dire threat. At a meeting of water activists and experts in December 2016 called India Rivers Week, information and ground reports from 290 rivers across the country were analysed and the verdict was chilling: 205 (over 70%) of them, including most of the big rivers, were in the critical or `red' category . Their water flows were diminished, tributaries were dwindling or cut off, pollution was rampant, river banks built up and encroached, and catchment areas denuded of forests.

THREAT TO RIVERS

“Most rivers are overexploited by constructing structures like check dams, weirs, dams, so the minimum flow (called `environmental' flow) required for the river eco-systems is not materialized. Studies show the current minimum flow is only one-third of what is required. Many small tributaries of the rivers are disconnected due to population pressure, road development etc.,“ K Palanisami, professor emeritus at the International Water Management Institute, told.

“Another factor for slow dying of the rivers is the rainfall pattern which has changed a lot in the recent years, thus making the river flows unsustainable. As a result, people start misusing them in terms of sand mining, encroachment, polluting,“ he added.

Himanshu Thakkar of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP) told that other factors damaging rivers included construction of hydropower projects, lack of understanding or appreciation of rivers and their roles, dumping of waste, climate change, riverfront development and destruction of biodiversity . “In India, dams and hydropower projects are possibly the biggest reasons for the destroyed threatened state of our rivers,“ he alleged.This is a controversial claim because there are many who say dams are necessary for meeting food and energy needs of a growing population. But water conservationists counter this by saying that a more sustainable path--with less wasteful consumption--was ignored.

FORESTS

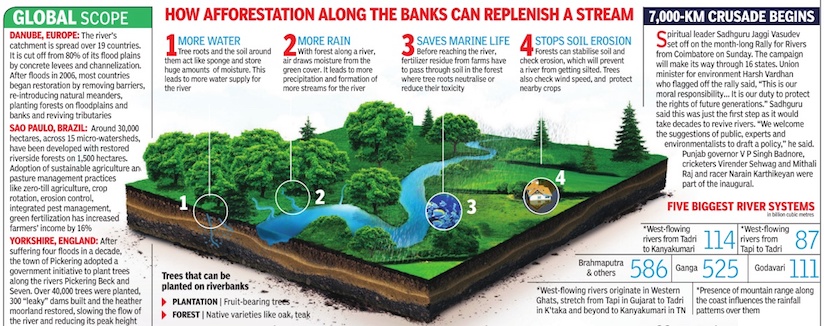

Apart from pollution and diversion, one important factor that doesn't get that much attention is forests. Not only do forests help in making rain, they also act as pumps that draw in the rain-laden winds from the seas.

“Much of the rain that falls in some regions is moisture that has been returned to the atmosphere from locations downwind-and forests are particularly effective at providing such recycled moisture,“ Douglas Sheil, professor at Norwegian University of Life Sciences and associated with Center for International Forest Research, Indonesia, explained.

Forests also provide tiny particles like pollen and spores around which raindrops can condense, he said. Though forest cover has slightly improved in the past few decades, it is far less than it used to be earlier. Moreover, dense forest cover has declined to be replaced by open forest with much less leaf density .

Deforestation in catchment areas is particularly high leading to deprivation of water flows to rivers through run-offs.

In short, India's life-sustaining rivers are dying a slow death. A complete policy overhaul is needed to rejuvenate them. People of the country need to be involved in this endeavour, otherwise it will fail like interventions in the past.

Water table depletes, migration increases

Telangana, 2017

Syed Akbar, River of migration through Telangana, September 16, 2017: The Times of India

Lakhs Of Farm Hands Head For Cities As Poor Water Mgmt Creates Scarcity, Leaves Land Dry

It's a blazing afternoon on the edge of the Red Corridor. Buses plying through Sivannagudem and neighbouring vil lages in Nalgonda are running almost empty; the place is virtually deserted except for a few elderly residents and some children.

A local barber, Satyanarayana, says, “The monsoon failed, everyone was forced to leave in search of employment in big cities.“

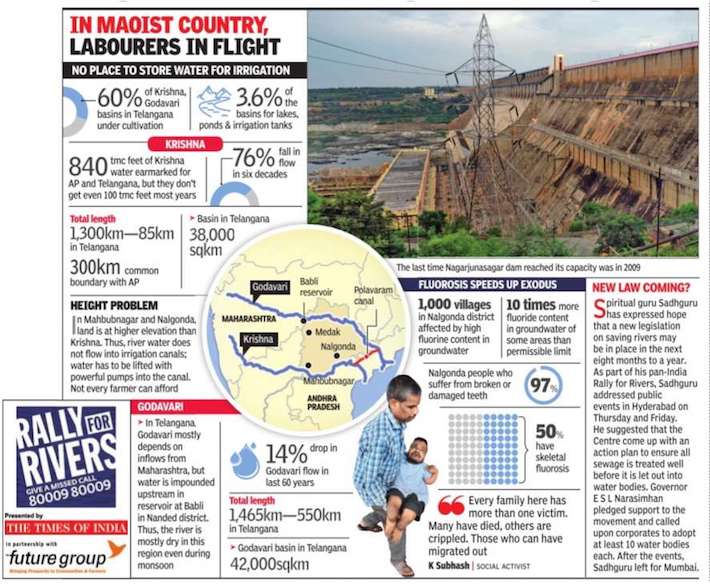

Across Telangana, the story repeats itself.Mahbubnagar, Nalgonda, Medak, they are all afflicted by acute water shortage--despite the presence of two major rivers. Mahbubnagar is where Krishna enters Telangana; Tungabhadra also passes through here. Nalgonda, in fact, hosts Asia's biggest masonry dam-Nagarjunasagar--and Medak is graced by Manjira, a tributary of the Godavari, besides several streams and rivulets which are in spate during monsoon.

This year, too, there's been no reduction in annual mean rainfall in Telangana (850-900 mm) but lack of watershed management has created scarcity . Impounding of Krishna and Godavari's inflows by Maharashtra and Karnataka did not help matters either.

Migration, though steady for three decades, has increased at the same pace as the water table has depleted.

Farm hands make up the exodus, Mahbubnagar sending the biggest contingent in south India, most heading to construction sites. Karimnagar accounts for maximum labourers to the Gulf.

Activists blame lack of water conservation for the perennial drought. “ At least now the state has embarked on a plan to conserve rain and river water in mega ponds here,“ says environment activist S Srinivas.

Dependence on groundwater has told even on the health of the local population. Around 1,000 villages in Nalgonda are battling effects of high fluorine content. The WHO limit for fluoride in drinking water is one mg per litre, but it's up to 10 times more in some places here. Many suffer from fluorosis, a disease that affects several parts of the body .Those with congenital fluorosis have stunted growth.

Deprived of potable water and sources to irrigate farmlands seems an irony for a district traversed by the Krishna and its tributaries. “Every family here has more than one victim. Those who can afford have migrated,“ says K Subhash, who leads an effort to create awareness about fluorosis.

The formation of Telangana state has now raised hopes of a shift in the narrative. A government project to dredge lakes and ponds and divert river waters when they overflow is underway .

Measures taken to prevent pollution, shrinkage

Afforestation along banks replenishes steams

Subodh Varma, Greens turn the course of dying rivers, September 4, 2017: The Times of India

SURVIVAL TALES: Arid Alwar In Rajasthan & Southern TN Show The Way By Conserving Rainwater, Recharging Wells, Reviving Streams

Rejuvenation of dying riv ers of India is a complex task. The key concern is people living in a river's vicinity, who are con nected to it in myriad ways. While governments approach this task through policy measures, laws and regulations, non-governmental bodies have started from the other end, taking up small manageable portions of a river, and built sustainable water management systems. Both approaches are complementary and essential. Take the case of the Pambar and Kottakariar rivers in southern Tamil Nadu. Their basin is afflicted by virtually all possible problems--deforestation, rainfall deficit, declining flow, encroached water course, vulnerability to flood and drought, and sand mining from the river bed. Tamil Nadu's fabled water tank (oorani) system, nurtured by flowing rivers and meant for saving up scarce rainfall for later use, was in tatters, silted and often built up.

So, DHAN Foundation, an NGO, with support from Axis Bank Foundation, started revitalizing the water management system in the area in 2011. By renovation of 668 water bodies, an additional storage capacity of 1.55 lakh cubic metres was created, which assured 11,953 families of water for irrigation. Percolation from tanks and ponds rejuvenated over 2,550 borewells, ensuring drinking water to 15,482 families. And, with people managing the resource more efficiently , the two rivers were revitalised. DHAN has now extended this work downstream.

There are many such efforts all over the country . In Rajasthan, the Tarun Bharat Sangh, an NGO led by `Waterman' Rajinder Singh, has transformed an area in the arid Alwar district by retaining rainfall, recharging wells and revitalizing the streams there.

Forests play an important role in these efforts because of their ability to act as a pump, drawing in warm moisture-laden winds from oceans and nearby water bodies, says K Palanisami of the International Water Management Institute. “For example, in recent years, agro-forestry in Abu Dhabi and Dubai has increased using recycled domestic water, and as a result they get more rains than before,“ he told TOI.

In an innovative solution to both waste water disposal and deforestation, Pune-based BAIF Research and Devel 5 opment Foundation (BRDF) used h treated waste water to irrigate eroded barren hillocks at Ghansoli in the d Thane-Belapur industrial area of Navi , Mumbai. “In five-six years, the barren 2 hill, spread over 200 hectares, was g transformed into a lush green forest, o which attracted over 50 species of fauna and promoted eco-tourism,“ said Narayan Hegde of BRDF .r Other threats like encroachment n on banks, sand mining, dumping of sewage and effluents need strong govd ernmental intervention through laws y and robust implementation. The sad d experience of the Ganga and Yamuna Action Plans, which consumed crores n of rupees without much change in o these two rivers' condition, shows that policies need to be dovetailed with cred ating awareness and participation.

Unbridled commercialization needs to be curbed and rivers made central to t planning, with the people who depend d on them being part of the process.d “If humanity is desirous of a watert secure future, there is no alternative but to let the rivers be. Anything h short is living in a fool's paradise,“ says , Manoj Misra of Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan, a campaign to save Yamuna.

River Kal improves after CETPs near Mumbai

CETPs Near Mumbai Clean Up Act After Court Orders, River Kal Gets A Breather

Sadanand Patward han's village is sand wiched between phase 1 and 2 of Ma had MIDC, one of several industrial clusters in Maharashtra's western region. His ancestral home is on the banks of the oncepristine Kal River, a tributary of the Savitri, which flows through Raigad district. By 1988, chemical and textile companies were spewing untreated effluents into them. And by 2007, Mahad was among top 10 of the Blacksmith Institute's `Dirty Thirty'--a list of the world's most polluted places. In its report, Blacksmith Institute noted that “approximately 1,800 tonnes of hazardous sludge had accumulated“ at the Mahad Common Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP).

Today , the picture is rosier.In 2012, the CETP began pulling up its socks following a series of Bombay high court orders.They upgraded infrastructure, installed an online monitoring system to check the quality of effluent and forced industries to pre-treat waste so the CETP wouldn't be burdened. They even got ISO certification.

By January 2013, the HC recorded that Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) levels a valuable test for assessing organic pollution had plummeted to a monthly average of 356mgL.This was higher than the prescribed standard of 250mgL but a far cry from its all-time high of 7,320mgL in 2005. As of September 4, 2017, the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (MPCB) recorded Mahad's COD at 144mgL.

Mahad's story is not unique.Many other CETPs have followed its lead. The turnaround can be traced to a 2011 PIL filed by activist Nicholas H Almeida, a trustee of Watchdog Foundation. The PIL resulted in many court orders for monitoring malfunctioning CETPs, action against industrial units flouting pre-treatment norms and setting up of new CETPs where the pollution load exceeded a plant's capacity. In Tarapur, the CETP had a capacity of 25 million litres per day (MLD) but was handling 40 MLD. Perhaps the most farsighted directive was forcing the MPCB to test In partnership with CETPs' effluents every week, says Godfrey Pimenta, also a trustee at Watchdog.

P Anbalagan, member sec retary of MPCB, says that when he joined in 2015, just 8-10 of the 26 CETPs met the standards.Today , he says that number has jumped to 18-20, thanks to stringent monitoring, night samplings and surprise checks.

What's more, 600-plus industrial units flouting environmental laws have been shut down across Maharashtra. As for CETPs still exceeding permissible standards, Anbalagan claims they've shown improvement and are now just marginally above prescribed levels.

Experts say this must be weighed against the volume of effluent discharged, as impact in some cases would be greater.And suspended solids (SS) and total dissolved solids (TDS) levels for many CETPs remain in the red zone. MPCB says “this shouldn't be an issue for coastal discharge where there is sufficient water volume for dilution“ but environmentalists do not agree. Shyam Asolekar, a professor at IIT-Bombay's Centre for Environmental Science and Engineering, says the result of flushing large quantities of SS and TDS into the ocean will only be apparent decades from now, once it's too late to rectify . He also fears current standards for COD and BOD are too lax.

While the situation is better now, activists insist it is far from perfect. The fight continues.