Rythu Bandhu direct benefit transfer to farmers

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

In brief

2017-19

From: Sribala Vadlapatla, The KCR trump card that Centre wants to adopt, January 13, 2019: The Times of India

From: Sribala Vadlapatla, The KCR trump card that Centre wants to adopt, January 13, 2019: The Times of India

Why India’s First Direct Benefit Transfer Scheme For Farmers, Credited With Bringing TRS Back In Telangana, Has Caught NDA Govt’s Attention

When farmers from across the country reached Delhi to protest in November last year, those from Telangana were missing. Was it possible that while farm distress had gripped an entire nation, Telangana was immune to the problem?

Next month, in December, BJP lost the assembly elections in three heartland states, booted out by angry farmers. But in Telangana, K Chandrasekhar Rao returned for a second term, winning a landslide.

So what was it that KCR had got right? At the heart of it all is KCR’s Rythu Bandhu scheme — India’s first direct benefit transfer (DBT) scheme for farmers. Launched in 2017, it benefited over 57 lakh farmers.

This pioneering scheme could well become a template that the Modi government might follow as it tries to assuage farmers ahead of the 2019 Lok Sabha polls.

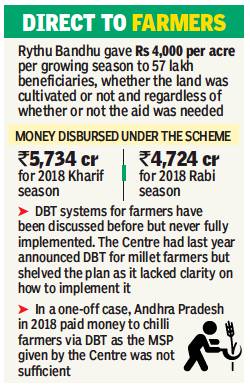

The scheme is simple — every farmer in Telangana last year got Rs 4,000 per acre per growing season, whether he cultivated his land or not and whether he needed that money or not. For all practical purposes, each farmer got Rs 8,000 per acre in his bank account as DBT. It cost the government about Rs 10,000 crore.

The political impact of the scheme can be gauged from the KCR-led Telangana Rashtra Samithi’s sweeping victory in the state, bagging 88 of the 119 seats in the assembly elections and completely decimating a united opposition of Congress, TDP, Telangana Jana Samithi and CPI.

States like Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, and West Bengal have already either announced similar schemes or are planning to implement one soon. “We even received a call from the Union agriculture ministry immediately after the election result,” a senior Telangana official said.

KCR had kept his farmers happy in the first four years that he ruled the newly formed state. After coming to power in 2014, he had announced a Rs 1 lakh per farmer loan waiver scheme. Once the waiver scheme lapsed in 2017, he immediately launched Rythu Bandhu.

The TRS government released the payment for the Rabi season under Rythu Bandhu just a few days ahead of the December 7 polling day last year. And during his campaign, KCR promised to hike the payment per acre to Rs 10,000 a year — Rs 5,000 each for the Rabi and Kharif seasons.

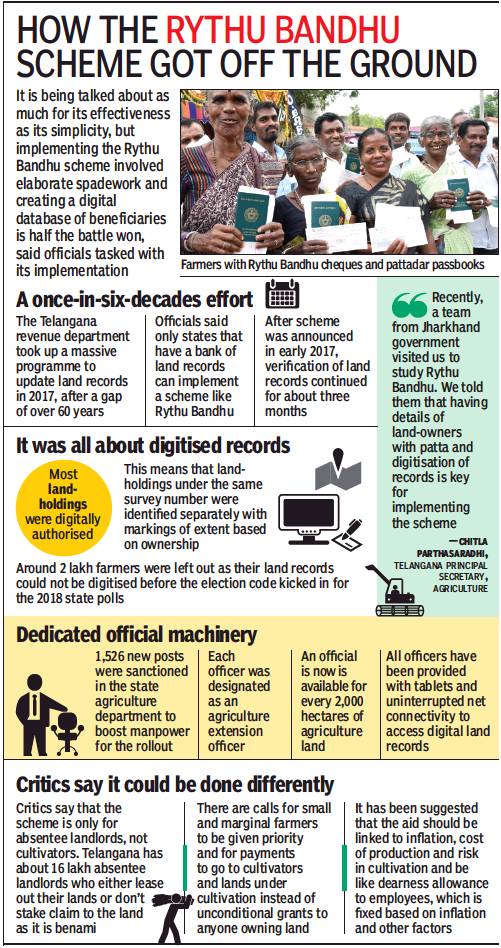

Despite its simplicity, it was not an easy a scheme to implement. This KCR brainchild needed an entire year of preparation, with the state revenue department taking up a massive programme to update land records in 2017, after a gap of more than 60 years.

Telangana principal secretary of agriculture, Chitla Parthasaradhi said only states that have a bank of land records can implement this scheme. “A Jharkhand government team visited us recently to study Rythu Bandhu. We told them that having details of landowners with patta and digitisation of records is key to implementing such a scheme, along with the requisite budget, of course,” he told TOI.

After the scheme was announced in early 2017, verification of land records continued for about three months. Most land-holdings were digitally authorised.

All that legwork also contributed to Rythu Bandhu earning the distinction of being perhaps the first-ever farm income support scheme in India that conforms to World Trade Organisation (WTO) guidelines.

WTO is against signatory countries providing input-based support and subsidies to farmers and encourages direct benefit transfer instead. Schemes like Rythu Bandhu fall under ‘decoupled income support’ category, where farmers can use the money according to their convenience.

“In India, we mostly go against WTO norms and provide support price or product-based support for seeds, fertilisers, pesticides and labour to farmers, who are then pushed into opting for crops that receive input support. That, in turn, causes market disturbance and ecological imbalance,” said GV Ramanjaneyulu, an agriculture scientist and activist.

Experts say that among the ecological imbalances that can be attributed to the MSP model are excessive cultivation of paddy in many parts of the country and cotton in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. Also, states like Punjab continue to cultivate water-intensive paddy in a big way despite facing a severe shortage of groundwater in many parts of the state.

But while it may appear to be the panacea for all farming issues, the Rythu Bandhu scheme is not without its critics.

O Kavita, a tenant farmer from the backward Devarakonda area in the common Nalgonda district, said, “I cultivate four acres on lease. I work on paddy, cotton and red gram but I did not get the benefit of the scheme despite slogging day and night. I know many rich landowners got huge amounts. Even NRIs got the Rs 8,000. The scheme should be only for cultivators, not absentee landlords. We have approached the high court to change the rules.”

Data from the National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj (NIRDPR) shows that Telangana has about 16 lakh absentee landlords who either lease out their lands or don’t stake claim to the land as it is benami property.

Also, many feel that small and marginal farmers should be given priority. “Most big farmers can bear the risks but we depend on small land-holdings and our dependence on crop income is greater. The government should give marginal farmers more support,” said K Ranga Reddy, a marginal farmer who owns three acres of land in Bhadradri district.

Activists say the scheme needs to be targeted at cultivators and at land under cultivation instead of unconditionally releasing money to anyone owning land. The payments, they add, should be linked to inflation, cost of production and risk in cultivation and be like dearness allowance to employees, which is fixed based on inflation and other factors.