Sikh Religion

(→Smarta Sect) |

(→Swami-Narayan Sect) |

||

| Line 196: | Line 196: | ||

which they are threatened, to devise the best plans for averting it and to choose the generals who are to lead their armies against the common enemy." The first Guru-Mata was assembled by Guru Govind, and the latest was called in 1805, when the British Army pursued Holkar into the Punjab. The Sikh Army was known as Dal Khalsa, or the Army of God, khdlsa being an Arabic word meaning one's own.^ At the height of the Sikh power the followers of this religion only numbered a small fraction of the population of the Punjab, and its strength is now declining. In 191 i the Sikhs were only three millions in the Punjab population of | which they are threatened, to devise the best plans for averting it and to choose the generals who are to lead their armies against the common enemy." The first Guru-Mata was assembled by Guru Govind, and the latest was called in 1805, when the British Army pursued Holkar into the Punjab. The Sikh Army was known as Dal Khalsa, or the Army of God, khdlsa being an Arabic word meaning one's own.^ At the height of the Sikh power the followers of this religion only numbered a small fraction of the population of the Punjab, and its strength is now declining. In 191 i the Sikhs were only three millions in the Punjab population of | ||

twenty-four millions. | twenty-four millions. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Vishnu Vaishnava, Vishnuite Sect== | == Vishnu Vaishnava, Vishnuite Sect== | ||

Revision as of 21:55, 13 February 2014

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Contents |

Sikh Religion

LIST OF PARAGRAPHS 1 . Foundation of SikJdsiii—Bdba 5 . Character of the Ndnakpanthis Ndfiak. and Sikh sects. 2. The earlier Gurus. 6. The Akdlis. 3. Guru Govind Singh. 7. The Sikh Council or Guru- 4. Sikh initiation aitd rules. Mdta. Their coviu/unal meal.

Sikh, Akali

The Sikh religion and the history of the i. Founda- tion of Sikhism — Sikhs have been fully described by several writers, and all that is intended in this article is a brief outline of the main Haba tenets of the sect for the benefit of those to whom the more ^"^ important works of reference may not be available. The Central Provinces contained only 2337 Sikhs in 191 i, of whom the majority were soldiers and the remainder probably timber or other merchants or members of the subordinate engineering service in which Punjabis are largely employed.

The following account is taken from Sir Denzil Ibbetson's Census Report of the Punjab for 1 8 8 1 : " Sikhism was founded by Baba Nanak, a Khatri of the Punjab, who lived in the fifteenth century. But Nanak was not more than a religious reformer like Kabir, Ramanand, and the other Vaishnava apostles. He preached the unity of God, the abolition of idols, and the disregard of caste distinctions.^ His doctrine and life were eminently gentle and unaggressive. He was succeeded by nine gurus, the last and most famous of whom, Govind Singh, died in 1708. " The names of the gurus were as follows :

1. Baba Nanak 1469-1538-9 2. Angad 1 539-1 552 3. Amar Das 1552-1574 1 See article Nanakpanthi for an account of Nanak's creed.

2. The earlier Gurus. 4- 5- 6. 7- 8. 9- lo. Ram Das Arjun Har Govind Har Rai Har Kishen Teg Bahadur Govind Sinijb 1574-1581 1581-1606 1606-1645 1645-1661 1661-1664 1664-1675 1675-1708 " Under the second Guru Angad an intolerant and ascetic spirit began to spring up among the followers of the new tenets ; and had it not been for the good sense and firmness displayed by his successor, Amar Das, who excommunicated the Udasis and recalled his followers to the mildness and tolerance of Nanak, Sikhism would probably have merely added one more to the countless orders of ascetics or devotees which arc wholly unrepresented in the life of the people. The fourth gum, Ram Das, founded Amritsar ; but it was his successor, Arjun, that first organised his following. He gave them a written rule of faith in the Granth or Sikh scripture which he compiled, he provided a common rallying- point in the city of Amritsar which he made their religious centre, and he reduced their voluntary contributions to a systematic levy which accustomed them to discipline and paved the way for further organisation. He was a great trader, he utilised the services and money of his disciples in mercantile transactions which extended far beyond the con- fines of India, and he thus accumulated wealth for his Church.

" Unfortunately he was unable wholly to abstain from politics ; and having become a political partisan of the rebel prince Khusru, he was summoned to Delhi and there im-

prisoned, and the treatment he received while in confinement hastened, if it did not cause, his death. And thus began that Muhammadan persecution which was so mightily to change the spirit of the new faith. This was the first turning-point

in Sikh history ; and the effects of the persecution were

immediately apparent. Arjun was a priest and a merchant ; his successor, Har Govind, was a warrior. He abandoned the gentle and spiritual teaching of Nanak for the use of arms and the love of adventure. He encouraged his followers to eat flesh, as giving them strength and daring ; he substituted

zeal in the cause for saintlincss of life as the i)rice of salva-

tion ; and he developed the organised disciplincMvliich Arjun

had initiated. He was, however, a military adventurer rather than an enthusiastic zealot, and fought either for or against the Muhammadan empire as the hope of immediate gain dictated. His policy was followed by his two successors ; and under Teg Bahadur the Sikhs degenerated into little better than a band of plundering marauders, whose internal factions aided to make them disturbers of the public peace. Moreover, Teg Bahadur was a bigot, while the fanatical Aurangzeb had mounted the throne of Delhi. Him therefore Aurangzeb captured and executed as an infidel, a robber and a rebel, while he cruelly persecuted his followers in common with all who did not accept Islam.

" Teg Bahadur was succeeded by the last and greatest 3. Guru guru, his son Govind Singh ; and it was under him that ?.°"'^ what had sprung into existence as a quietist sect of a purely religious nature, and had become a military society of by no means high character, developed into the political organisa- tion which was to rule the whole of north-western India, and to furnish the British arms their stoutest and most worthy opponents. For some years after his father's execu- tion Govind Singh lived in retirement, and brooded over his personal wrongs and over the persecutions of the Musalman fanatic which bathed the country in blood. His soul was filled with the longing for revenge ; but he felt the necessity for a larger following and a stronger organisation, and, follow- ing the example of his Muhammadan enemies, he used his religion as the basis of political power. Emerging from his retirement he preached the Khalsa, the pure, the elect, the liberated.

He openly attacked all distinctions of caste, and taught the equality of all men who would join him ; and instituting a ceremony of initiation, he proclaimed it as the pdhul or ' gate ' by which all might enter the society, while he gave to its members the prasdd or communion as a sacrament of union in which the four castes should eat of one dish. The higher castes murmured and many of them left him, for he taught that the Brahman's thread must be broken ; but the lower orders rejoiced and flocked in numbers to his standard. These he inspired with military ardour, with the hope of social freedom and of national independence, and with abhorrence of the hated Muhammadan. He grave

them outward signs of their faith in the unshorn hair, the short drawers, and the bkie dress ; he marked the military nature of their calling by the title of Singh or ' lion,' by the wearing of steel, and by the initiation by sprinkling of water with a two-edged dagger ; and he gave them a feeling of personal superiority in their abstinence from the unclean tobacco. " The Muhammadans promptly responded to the chal- lenge, for the danger was too serious to be neglected ; the Sikh army was dispersed, and Govind's mother, wife and children were murdered at Sirhind by Aurangzeb's orders. The death of the emperor brought a temporary lull, and a year later Govind himself was assassinated while fighting the Marathas as an ally of Aurangzeb's successor.

He did not live to see his ends accomplished, but he had roused the dormant spirit of the people, and the fire which he lit was only damped for a while. His chosen disciple Banda suc- ceeded him in the leadership, though never recognised as gum. The internal commotions which followed upon the death of the emperor, Bahadur Shah, and the attacks of the Marathas weakened the power of Delhi, and for a time Banda carried all before him ; but he was eventually con- quered and captured in A.D. 1 7 1 6, and a period of persecution followed so sanguinary and so terrible that for a generation nothing more was heard of the Sikhs.

How the troubles of the Delhi empire thickened, how the Sikhs again rose to prominence, how they disputed the possession of the Punjab with the Mughals, the Marathas and the Durani, and were at length completely successful, how they divided into societies under their several chiefs and portioned out the Province among them, and how the genius of Ranjit Singh raised him to supremacy and extended his rule beyond the limits of the Punjab, are matters of political and not of religious history. No formal alteration has been made in the Sikh religion since Govind Singh gave it its military shape ; and though changes have taken place, they have been merely the natural result of time and external influences, 4- Sikh "The word Sikh is said to be derived from the common and rules. Hiudu tcrm Scwak and to mean simply a disciple; it may be applied thcrcfcjre t(j the followers of Nanak who held

aloof from Govind Singh, but in practice it is perhaps understood to mean only the latter, while the Nanakpanthis are considered as Hindus. A true Sikh always takes the termination Singh to his name on initiation, and hence they are sometimes known as Singhs in ^ distinction to the Nanakpanthis. A man is also not born a Sikh, but must always be initiated, and the pdhul or rite of baptism cannot take place until he is old enough to understand it, the earliest age being seven, while it is often postponed till manhood. Five Sikhs must be present at the ceremony, when the novice repeats the articles of the faith and drinks sugar and water stirred up with a two-edged dagger. At the initiation of women a one-edged dagger is used, but this is seldom done.

Thus most of the wives of Sikhs have never been initiated, nor is it necessary that their children should become Sikhs when they grow up. The faith is unattractive to women owing to the simplicity of its ritual and the absence of the feasts and ceremonies so abundant in Hinduism ; formerly the Sikhs were accus- tomed to capture their wives in forays, and hence perhaps it was considered of no consequence that the husband and wife should be of different faith. The distinguishing marks of a true Sikh are the five Kakkas or Ks which he is bound to carry about his person : the Kes or uncut hair and unshaven beard ; the KacJih or short drawers ending above the knee ; the Kasa or iron bangle ; the KJuuida or steel knife ; and the Kanga or comb.

The other rules of conduct laid down by Guru Govind Singh for his followers were to dress in blue clothes and especially eschew red or saffron-coloured garments and caps of all sorts, to observe personal cleanliness, especially in the hair, and practise ablutions, to eat the flesh of such animals only as had been killed hy j'atka or decapitation, to abstain from tobacco in all its forms, never to blow out flame nor extinguish it with drinking-water, to eat with the head covered, pray and recite passages of the Granth morning and evening and before all meals, reverence the cow, abstain from the worship of saints and idols and avoid mosques and temples, and worship the one God only, neglecting Brahmans and Mullas, and their scriptures, teaching, rites and religious VOL. I Y

symbols. Caste distinctions he positively condemned and instituted the prasdd or communion, in which cakes of flour, butter and sugar are made and consecrated with certain ceremonies while the communicants sit round in prayer, and then distributed equally to all the faithful present, to whatever caste they may belong. The above rules, so far as they enjoin ceremonial observances, are still very generally obeyed. But the daily reading and recital of the Granth is discontinued, for the Sikhs are the most uneducated class in the Punjab, and an occasional visit to the Sikh temple where the Granth is read aloud is all that the villager thinks necessary. Blue clothes have been discontinued save by the fanatical Akali sect, as have been very generally the short drawers or Kachh.

The prohibi- tion of tobacco has had the unfortunate effect of inducing the Sikhs to take to hemp and opium, both of which are far more injurious than tobacco. The precepts which forbid the Sikh to venerate Brahmans or to associate himself with Hindu worship are entirely neglected ; and in the matter of the worship of local saints and deities, and of the employment of and reverence for Brahmans, there is little, while in current superstitions and superstitious practices there is no difference between the Sikh villager and his Hindu brother." ^ 5. Char- It scems thus clear that if it had not been for the Ni.nak^^'^^ political and military development of the Sikh movement, it panthisand would in time have lost most of its distinctive features and Si sects, j^^^g come to be considered as a Hindu sect of the same character, if somewhat more distinctive than those of the Nanakpanthis and Kablrpanthis.

But this development and the founding of the Sikh State of Lahore created a breach between the Sikhs and ordinary Hindus wider than that caused by their religious differences, as was sufficiently demonstrated during the Mutiny. In their origin both the Sikh and Nanakpanthi sects appear to 1 Here again, Sir U. Ibbetson notes, number of deities, and their answer in it is often the women who arc the every case has been that tliey do not original offenders : " I have often asked themselves believe in them; but their Sikhs how it is that, believing as they women do, and to please them they are do in only one God, they can put any obliged to pay attention to what the faith in and render any obedience to Brfdimans say." Ikahmans who acknowledge a largo

have been mainly a revolt against the caste system, the supremacy of Brahmans and the degrading mass of super- stitions and reverence of idols and spirit-worship which the Brahmans encouraged for their own profit. But while Nanak, influenced by the observation of Islamic mono- theism, attempted to introduce a pure religion only, the aim of Govind was perhaps political, and he saw in the caste system an obstacle 'to the national movement which he desired to excite against the Muhammadans.

So far as the abolition of caste was concerned, both reformers have, as has been seen, largely failed, the two sects now recognising caste, while their members revere Brahmans like ordinary Hindus. The Akalis or Nihangs are a fanatical order of Sikh 6. The ascetics. The following extract is taken from Sir E. Maclagan's account of them : ^ " The Akalis came into prominence very early by their stout resistance to the innovations introduced by the Bairagi Banda after the death of Guru Govind ; but they do not appear to have had much influence during the following century until the days of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. They constituted at once the most unruly and the bravest portion of the very unruly and brave Sikh army.

Their headquarters were at Amritsar, where they constituted themselves the guardians of the faith and assumed the right to convoke synods. They levied offerings by force and were the terror of the Sikh chiefs. Their good qualities were, however, well appreciated by the Maharaja, and when there were specially fierce foes to meet, such as the Pathans beyond the Indus, the Akalis were always to the front.

" The Akali is distinguished very conspicuously by his dark -blue and checked dress, his peaked turban, often surmounted with steel quoits, and by the fact of his strutting about like Ali Baba's prince with his ' thorax and abdomen festooned with curious cutlery.' He is most particular in retaining the five Kakkas, and in preserving every outward form prescribed by Guru Govind Singh. Some of the Akalis wear a yellow turban underneath the blue one, leaving a yellow band across the forehead. The yellow turban is 1 Punjab Census Report (1891), para. 107.

7. The Sikh Council or Guru- Mata. Their com munal meal. worn by many Sikhs at the Basant Panchmi, and the Akalis are fond of wearing it at all times. There is a couplet by Bhai Gurdas which says : Stall, Sufed, Surkh, Zardae, Jo pahne, sot Giirbhaij or, * Those that wear black (the Akalis), white (the Nirmalas), red (the Udasis) or yellow, are all members of the brother- hood of the Sikhs.' " The Akalis do not, it is true, drink spirits or eat meat as other Sikhs do, but they are immoderate in the consump- tion of bhang.

They are in other respects such purists that they will avoid Hindu rites even in their marriage ceremonies. " The Akali is full of memories of the glorious day of the Khalsa ; and he is nothing if he is not a soldier, a soldier of the Guru. He dreams of armies, and he thinks in lakhs. If he wishes to imply that five Akalis are present, he will say that ' five lakhs are before you ' ; or if he would explain he is alone, he will say that he is with ' one and a quarter lakhs of the Khalsa.' You ask him how he is, and he replies that ' The army is well ' ; you inquire where he has come from, and he says, '

The troops marched from Lahore.' The name Akali means ' immortal.' When Sikhism was politically dominant, the Akalis were accus- tomed to extort alms by accusing the principal chiefs of crimes, imposing fines upon them, and in the event of their refusing to pay, preventing them from performing their ablutions or going through any of the religious ceremonies at Amritsar." The following account was given by Sir J. Malcolm of the Guru-Mata or great Council of the Sikhs and their religious meal : ^ "

When a Guru-Mata or great national Council is called on the occasion of any danger to the country, all the Sikh chiefs assemble at Amritsar. The assembly is convened by the Akalis ; and when the chiefs meet upon this solemn occasion it is concluded that all private animosities cease, and that every man sacrifices his personal feelings at the shrine of the general good. ' Accounl of the Sikhs, Asiatic Researches.

" When the chiefs and principal leaders are seated, the Adi-Granth and Dasama Padshah Ka Granth ^ are placed before them. They all bend their heads before the Scriptures and exclaim, ' Wah Gtiruji ka Khdlsa ! zuah Guriiji ka Fateh ! ' ' A great quantity of cakes made of wheat, butter and sugar are then placed before the volumes of their sacred writings and covered with a cloth. These holy cakes, which are in commemoration of the injunction of Nanak to eat and to give to others to eat, next receive the salutation of the assembly, who then rise, while the Akalis pray aloud and the musicians play. The Akalis, when the prayers are finished, desire the Council to be seated. They sit down, and the cakes are uncovered and eaten by all classes of the Sikhs, those distinctions of tribe and caste which are on other occasions kept up being now laid aside in token of their general and complete union in one cause.

The Akalis proclaim the Guru-Mata, and prayers are again said aloud. The chiefs after this sit closer and say to each other, ' The sacred Granth is between us, let us swear by our Scriptures to forget all internal disputes and to be united.' This moment of religious fervour is taken to reconcile all ani- mosities. They then proceed to consider the danger with which they are threatened, to devise the best plans for averting it and to choose the generals who are to lead their armies against the common enemy." The first Guru-Mata was assembled by Guru Govind, and the latest was called in 1805, when the British Army pursued Holkar into the Punjab. The Sikh Army was known as Dal Khalsa, or the Army of God, khdlsa being an Arabic word meaning one's own.^ At the height of the Sikh power the followers of this religion only numbered a small fraction of the population of the Punjab, and its strength is now declining. In 191 i the Sikhs were only three millions in the Punjab population of twenty-four millions.

The name given to Hindus as repre- ^yj^Qgg special deity is the god Vishnu, and to a number of senting \ •' ° _ _' the sun. sccts wliich havc adopted various special doctrines based on the worship of Vishnu or of one of his two great incarna- tions, Rama and Krishna. Vishnu was a personification of the sun, though in ancient literature the sun is more often referred to under another name, as Savitri, Surya and Aditya. It may perhaps be the case that when the original sun-god develops into a supreme deity with the whole heavens as his sphere, the sun itself comes to be regarded as a separate and minor deity. His weapon of the cliakra or discus,

which was probably meant to resemble the sun, supports the view of Vishnu as a sun-god, and also his vdhan, the bird Garuda, on which he rides.

This is the Brahminy kite, a fine bird with chestnut plumage and white head and breast, which has been considered a sea-eagle. Mr. Dewar states that it remains almost motionless at a great height in the air for long periods ; and it is easy to understand how in these circumstances primitive people mistook it for the spirit of the sky, or the vehicle of the sun-god. It is propitious for a Hindu to see a Brfdiminy kite, especially on Sunday, the sun's day, for it is believed that the bird is then returning from Vishnu, whom it has gone to see on the previous even- ing.^ A similar belief has probably led to the veneration of the eagle in other countries and its association with the god of the sky or heavens, as in the case of Zeus, Similarly the Gayatri, the most sacred Hindu prayer, is addressed to the sun, and it could hardly have been considered so important unless the luminary was identified with one of the greatest Hindu gods. Every Brahman prays to the sun daily when he bathes in the morning. Vishnu's character as the pre- ' Bombay Ducks, p. 194.

server and fosterer of life is probably derived from the sun's

generative power, so conspicuous in India. As the sun is seen to sink every night into the earth, so 2. His it was thought that he could come down to earth, and Vishnu J"'^^"^" ^_ _ ' tions. has done this in many forms for the preservation of man-

kind. He is generally considered to have had ten incarnations, of which nine are past and one is still to come. The

incarnations were as follows : 1. As a great fish he guided the ark in which Manu the primeval man escaped from the deluge.

2. As a tortoise he supported the earth and poised it in its present position ; or according to another version he lay at the bottom of the sea while the mountain INIeru was set on its peak on his back, and with the serpent Vasuki as a rope round the mountain the ocean was churned by the gods for making the divine Amrit or nectar which gives immor- tality.

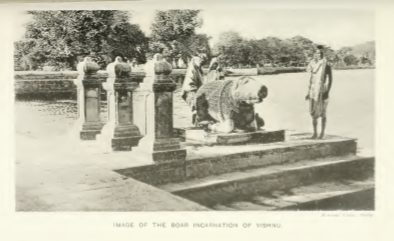

3. As a boar he dived under the sea and raised the earth on his tusks after it had been submerged by a demon.

4. As Narsingh, the man-lion, he delivered the world from the tyranny of another demon.

5. As Waman or a dwarf he tricked the King Bali, who had gained possession over the earth and nether world and was threatening the heavens, by asking for as much ground as he could cover in three steps. When his request was derisively granted he covered heaven and earth in two steps, but on Bali's intercession left him the nether regions and refrained from making the third step which would have covered tlicm.

6. As Parasurama ^ he cleared the earth of the Kshat- riyas, who had oppressed the r>ra]iman hermits and stolen the sacred cow, bj' a slaughter of them thrice seven times repeated. 7. As Rama, the divine king of Ajodhia or Oudh, he led an expedition to Ceylon for the recovery of his wite Sita, who had been abducted by Rawan, the demon king of ' For a suggested explanation of the myth of ravasur.iina sec article Panwar RajpQt.

Ceylon.

This story probably refers to an early expedition of the Aryans to southern India, in which they may have obtained the assistance of the Munda tribes, represented by Hanuman and his army of apes. 8. As Krishna he supported the Pandavas in their war against the Kauravas, and at the head of the Yadava clan founded the city of Dwarka in Gujarat, where he was after- wards killed. The popular group of legends about Krishna in his capacity of a cowherd in the forests of Mathura was perhaps at first distinct and afterwards combined with the story of the Yadava prince.

But it is in this latter char- acter as the divine cowherd that Krishna is most generally known and worshipped. 9. As Buddha he was the great founder of the religion known by his name ; the Brahmans, by making Buddha an incarnation of Vishnu, have thus provided a connecting link between Buddhism and Hinduism. In his tenth incarnation he will come again as Nishka- lanki or the stainless one for the final regeneration of the world, and his advent is expected by some Hindus, who worship him in this form. 3. Wor- In the Central Provinces Vishnu is worshipped as Vishnu and Narayan Deo, who is identified with the sun, or as Parmesh- Vaishnava yy^r, the supreme beneficent god. He is also much wor- doctrines. ..... . t-, _ •, -rr • ^ 1 1 • shipped m his incarnations as Kama and Krishna, and their images, with those of their consorts, Sita and Radha, are often to be found in his temples as well as in their own. These images are supposed to be subject to all the condi- tions and necessities incident to living humanity.

Hence in the daily ritual they are washed, dressed, adorned and even fed like human beings, food being daily placed before them, and its aroma, according to popular belief, nourishing the god present in the image. The principal Vishnuite sects are described in the article on Bairagi, and the dissenting sects which have branched off from these in special articles." The cult of Vishnu and his two main incarnations is the most prominent feature of modern Hinduism. The orthodox Vaishnava sects mainly ' Sec also article Ahlr. 2 Kabirpanthi, Nanakpanthi, Dadupanthi, Swami-Narayan, etc.

differed on the point whether the human soul or spirit was a part of the divine soul or separate from it, and whether it would be reabsorbed into the divine soul, or have a separate existence after death. But they generally regarded all human souls as of one quality, and hence were opposed to distinctions of caste. Animals also have souls or spirits, and the Vishnuite doctrine is opposed to the destruction of animal life in any form.

In the Bania caste the practices of Vaishnava Hindus and Jains present so little difference that they can take food together, and even intermarry. The creed is also opposed to suicide. Faithful worshippers of Vishnu will after his death be transported to his heaven, Vaikuntha, or to Golaka, the heaven of Krishna. The sect - mark of the Vaishnavas usually consists of three lines down the forehead, meeting at the root of the nose or below it. All three lines may be white, or the centre one black or red, and the outside ones white. They are made with a kind of clay called Gopi- chandan, and are sometimes held to be the impress of Vishnu's foot. To put on the sect-mark in the morning is to secure the god's favour and protection during the day.

Vam-Margi, Bam-Marg- Vama-Chari Sect

A sect who follow the worship of the female principle in nature and indulge in sensuality at their rites according to the precepts of the Tantras. The name signifies ' the followers of the crooked or left-handed path.' Their principal sacred text is the Rudra-Yamal-Damru Tantra, which is said to have been promulgated by Rudra or Siva through his Damru or drum at the end of his dance in Kailas, his heaven in the Hima- layas.

The Tantras, according to Professor Monier-Williams, inculcate an exclusive worship of Siva's wife as the source of every kind of supernatural faculty and mystic craft. The principle of female energy is known as Sakti, and is personi- fied in the female counterparts of all the Gods of the Hindu triad, but is practically concentrated in Devi or Kali. The five requisites for Tantra worship are said to be the five Makaras or words beginning with M : Madya, wine ; Mansa,

1 This article is based on Professor Iccted by Munshi Kanhya Lai of the Wilson's Hindu Sects, M. Chevrillon's Gazetteer Office. RoDiantic India, and some notes col-

flesh ; Matsya, fish ; Muclra, parched grain and mystic gesticulation ; and Maithuna, sexual indulgence. Among the Vam-Margis both men and women are said to assemble at a secret" meeting- place, arid their rite consists in the adoration of a naked woman who stands in the centre of the room with a drawn sword in her hand. The worshippers then eat fish, meat and grain, and drink liquor, and there- after indulge in promiscuous debauchery. The followers of the sect are mainly Brahmans, though other castes may be admitted.

The Vam-Margis usually keep their membership of the sect a secret, but their special mark is said to be a semicircular line or lines of red powder or vermilion on the forehead, with a red streak half-way up the centre, and a circular spot of red at the root of the nose.

They use a rosary of rudraksha or of coral beads, but of no greater length than can be concealed in the hand, or they keep it in a small purse or bag of red cloth. During worship they wear a piece of red silk round the loins and decorate themselves with garlands of crimson flowers. In their houses they worship a figure of the double triangle drawn on the ground or on a metal plate and make offerings of liquor to it.

They practise various magical charms by which they think they can kill their enemies. Thus fire is brought from the pyre on which a corpse has been burnt, and on this the operator pours water, and with the charcoal so obtained he makes a figure of his enemy in a lonely place under a pipal tree or on the bank of a river. He then takes an iron bar, twelve finger-joints long, and after repeating his charms pierces the figure with it. When all the limbs have been pierced the man whose efifigy has been so treated will die. Other methods will procure the death of an enemy in a certain number of months or cause him to lose a limb. Sometimes they make a rosary of io8 fruits of the dhatura^ and pierce the figure of the enemy through the neck after repeating charms, and it is supposed that this will kill him at once. 1 Dhatura alba, a plant sacred to Siva, whose seed is a powerful narcotic, and is used to poison travellers.

Wahhabi Sect

A puritan sect of Miihammadans. The sect was not recorded at the census, but it is probable that it has a few adherents in the Central Provinces. The Wahhabi sect is named after its founder, Muhammad Abdul Wahhab, who was born in Arabia in A.D. 1691. He set his face against all developments of Islam not warranted by the Koran and the traditional utterances of the Com- panions of the Prophet, afld against the belief in omens and worship at the shrines of saints, and condemned as well all display of wealth and luxury and the use of in- toxicating drugs and tobacco.

He denied any authority to Islamic doctrines other than the Koran itself and the utterances of the Companions of the Prophet who had received instruction from his lips, and held that in the interpretation and application of them Moslems must exer- cise the right of private judgment. The sect met with considerable military success in Arabia and Persia, and at one time threatened to spread over the Islamic world. The following is an account of the taking of Mecca by Saud, the grandson of the founder, in 1803: "The sanctity of the place subdued the barbarous spirit of the conquerors, and not the slightest excesses were committed against the people.

The stern principles of the reformed doctrines were, however, strictly enforced. Piles of green huqqas and Persian pipes were collected, rosaries and amulets were forcibly taken from the devotees, silk and satin dresses were demanded from the wealthy and worldly, and the whole, piled up into a heterogeneous mass, were burnt by the infuriated reformers. So strong was the feeling against the pipes and so necessary did a public example seem to be, that a respectable lady, whose delinquency had well- nigh escaped the vigilant eye of the Muhtasib, was seized and placed on an ass, with a green pipe suspended from her neck, and paraded through the public streets—a terrible warning to all of her sex who might be inclined to indulge in forbidden luxuries. When the usual hour of prayer arrived the myrmidons of the law sallied forth, and with leathern whips drove all slothful Moslems to their devotions. 1 This article consists entirely of ex- sect in the Rev. T. P. Hughes' Diction- tracts from the article on the Wahhabi ary of Islam.

The mosques were filled.

Never since the days of the Prophet had the sacred city witnessed so much piety and devotion. Not one pipe, not a single tobacco-stopper, was to be seen in the streets or found in the houses, and the whole population of Mecca prostrated themselves at least five times a day in solemn adoration." The apprehensions of the Sultan of Turkey were aroused and an army was despatched against the Wahhabis, which broke their political power, their leader, Saud's son, being executed in Constantinople in 1 8 1 8. But the tenets of the sect continued to be maintained in Arabia, and in 1822 one Saiyad Ahmad, a freebooter and bandit from Rai Bareli, was converted to it on a pilgrimage to Mecca and returned to preach its doctrines in India.

Being a Saiyad and thus a descendant of the Prophet, he was accepted by the Muhammadans of India as the true Khalifa or Mahdi, awaited by the Shiahs. Unheeded by the British Govern- ment, he traversed our provinces with a numerous retinue of devoted disciples and converted the populace to his reformed doctrine by thousands, Patna becoming a centre of the sect. In 1826 he declared 2l jihad ox religious war against the Sikhs, but after a four years' struggle was defeated and killed.

The sect gave some trouble in the Mutiny, but has not since taken any part in politics. Its reformed doctrines, however, have obtained a considerable vogue, and still exercise a powerful influence on Muham- madan thought. The Wahhabis deny the aiithority of Islamic tradition after the deaths of the Companions of the Prophet, do not illuminate or pay reverence to the shrines of departed saints, do not celebrate the birthday of Muhammad, count the ninety-nine names of God on their fingers and not on a rosary, and do not smoke.