Sunar

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. During scanning some errors are bound to occur. Some letters get garbled. Footnotes get inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot errors might like to correct them, and shift footnotes gone astray to their rightful place.

Contents |

Sunar

Sunar, Sonar, Soni

Hon-Potdar, tional caste of goldsmiths and silversmiths. The name derived from the Sanskrit Suvarna kdr, a worker in gold. In 191 1 the Sunars numbered 96,000 persons in the Central Provinces and 30,000 in Berar. They live all over the Province and are most numerous in the large towns. The caste appears to be a functional one of comparatively recent formation, and there is nothing on record as to its origin, except a collection of Brahmanical legends of the usual type. The most interesting of these as related by Sir H. Risley is as follows :

"In the beginning of time, when the goddess Devi was

busy with the construction of mankind, a giant called Sonwa-

Daitya, whose body consisted entirely of gold, devoured

her creations as fast as she made them. To baffle this

monster the goddess created a goldsmith, furnished him

with the tools of his art, and instructed him how to proceed.

- This article is partly based on an the Gold and Silver Industries, and on

article by Mr. Raghunath Prasad, information furnished Ijy Krishna Rao, E.A.C., formerly Deputy Super- Revenue Inspector, Mandla. intendent of Census, with extracts from ^ Tribes and Castes of Bengal, art. the late Mr. Nunn's Monograph on Sunar.

When the giant proposed to eat him, the goldsmith suggested

to him that if his body were polished his appearance would

be vastly improved, and asked to be allowed to undertake

the job. With the characteristic stupidity of his tribe the

giant fell into the trap, and having had one finger polished

was so pleased with the result that he agreed to be polished

all over. For this purpose, like Aetes in the Greek legend

of Medea, he had to be melted down, and the goldsmith,

who was to get the body as his perquisite, giving the head

only to Devi, took care not to put him together again.

The goldsmith, however, overreached himself. Not content with his legitimate earnings, he must needs steal a part of the head, and being detected in this by Devi, he and his descendants were condemned to be for ever poor." The Sunars also have a story that they are the descendants of one of two Rajput brothers, who were saved as boys by a Saraswat Brahman from the wrath of Parasurama when he was destroying the Kshatriyas. The descendants of the other brother were the Khatris.

This is the same story as is told by the Khatris of their own origin, but they do not acknowledge the connection with Sunars, nor can the Sunars allege that Saraswat Brahmans eat with them as they do with Khatris. In Gujarat they have a similar legend connecting them with Banias. In Bombay they also claim to be Brahmans, and in the Central Provinces a caste of goldsmiths akin to the Sunars call themselves Vishwa Brahmans.

On the other hand, before and during the time of the Peshwas, Sunars were not allowed to wear the sacred thread, and they were forbidden to hold their marriages in public, as it was considered unlucky to see a Sunar bridegroom. Sunar bridegrooms were not allowed to see the state umbrella or to ride in a palanquin, and had to be married at night and in secluded places, being subject to restrictions and annoyances from which even Mahars were frce.^ Their raison d'etre may possibly be found in the fact that the Brahmans, all-powerful in the Poona state, were jealous of the pretensions of the Sunars, and devised these rules as a means of suppressing them. It may be suggested that the Sunars, being workers at an important urban 1 Bombay Gazetteer, vol. xvii. p. 134.

industry, profitable in itself and sanctified by its association

with the sacred metal gold, aspired to rank above the other

artisans, and put forward the pretensions already mentioned,

because they felt that their position was not commensurate

with their deserts. But the Sunar is included in Grant-

Duff's list of the twenty-four village menials of a Maratha

village, and consequently he would in past times have ranked

below the cultivators, from whom he must have accepted the

annual presents of grain.

The caste have a number of subdivisions, nearly all of 2. internal which are of the territorial class and indicate the various ^^"'^^"'^^• localities from which it has been recruited in these Provinces. The most important subcastes are the Audhia from Ajodhia or Oudh ; the Purania or old settlers ; the Bundelkhandi from Bundelkhand ; the Malwi from Malwa ; the Lad from Lat, the old name for the southern portion of Gujarat ; and the Mair, who appear to have been the first immigrants from Upper India and are named after Mair, the original ancestor, who melted down the golden demon. Other small groups arc the Patkars, so called because they allow pat or widowmarriage, though, as a matter of fact, it is permitted by the great majority of the caste ; the Pandhare or ' White Sunars '

and the Ahir Sunars, whose ancestors must presumably have belonged to the caste whose name they bear. The caste have also numerous bainks or exogamous septs, which differ entirely from the long lists given for Bengal and the United Provinces, and show, as Mr. Crooke remarks, the extreme fertility with which sections of this kind spring up.

In the Central Provinces the names are of a titular or territorial nature. Examples of the former kind, that is, a title or nickname supposed to have been borne by the sept's founder, are : Dantele, one who has projecting teeth ; Kale, black ; Munde, bald ; Kolhlmare, a killer of jackals ; and Ladaiya, a jackal or a quarrelsome person. Among the territorial names are Narwaria from Narwar ; Bhilsainyan from Bhilsa ; Kanaujia from Kanauj ; Dilllwal from Delhi ; Kfdpiwal from Kalpi. Besides the bainks or septs by which marriage is regulated, they have adopted the Brahmanical eponymous ^(?/rrt:-names as Kashyap, Garg, Sandilya, and so on. These are employed on ceremonial occasions as when a gift is made

for the purpose of obtaining religious merit, and the gotraname of the owner is recorded, but they do not influence marriage. The use of them is a harmless vanity analogous to the assumption of distinguished surnames by people who were not born to them.

3. Mar- Marriage is forbidden within the sept. In some localiothCT^"

ties persons descended from a common ancestor may not

customs. intermarry for five generations, but in others a brother's

daughter may be wedded to a sister's son.

A man is forbidden to marry two sisters while both are alive, and after his wife's death he may espouse her younger sister, but not her elder one. Girls are usually wedded at a tender age, but some Sunars have hitherto had a rule that neither a girl nor a boy should be married until they had had smallpox, the idea being that there can be no satisfactory basis for a contract of marriage while either party is still exposed to such a danger to life and personal appearance ; just as it might be considered more prudent not to buy a young dog until it had had distemper. But with the spread of vaccination the Sunars are giving up this custom.

The marriage ceremony follows the Hindustani or Maratha ritual according to locality.^ In Betul the mother of the bride ties the mother of the bridegroom to a pole with the ropes used for tethering buffaloes and beats her with a piece of twisted cloth, until the bridegroom's mother gives her a present of money or cloth and is released. The ceremony may be designed to express the annoyance of the bride's mother at being deprived of her daughter. Polygamy is permitted, but people will not give their daughter to a married man if they can find a bachelor husband for her. Well-to-do Sunars who desire increased social distinction prohibit the marriage of widows, but the caste generally allow it.

4. Reii- The caste venerate the ordinary Hindu deities, and many of them have sects and return themselves as Vaishnavas, Saivas or Saktas. In some places they are said to make a daily offering to their melting-furnace so that it may bring them in a profit. When a child has been born they make a sacrifice of a goat to Dulha Deo, the marriage-god, on the following Dasahra festival, and the body of this must be ' See articles on Kunl;i and Kurmi. gion

eaten by the family only, no outsider being allowed to participate. In Hoshangabad it is stated that on the night before the Dasahra festival all the Sunars assemble beside a river and hold a feast. Each of them is then believed to take an oath that he will not during the coming year disclose the amount of the alloy which a fellow-craftsman may mix with the precious metals. Any Sunar who violates this agreement is put out of caste.

On the 15th day of Jeth (May) the village Sunar stops work for five days and worships his implements after washing them. He draws pictures of the goddess Devi on a piece of paper and goes round the village to affix them to the doors of his clients, receiving in return a small present.

The caste usually burn their dead and take the ashes to

the Nerbudda or Ganges ; those living to the south of the

Nerbudda always stop at this river, because they think that

if they crossed it to go to the Ganges, the Nerbudda

would be offended at their not considering it good enough.

If a man meets with a violent death and his body is lost,

they construct a small image of him and burn this with all

the proper ceremonies. Mourning is observed for ten or

thirteen days, and the sJirdddJi ceremony is performed on

the anniversary of a death, while the usual oblations are

offered to the ancestors during the fortnight of Pitr Paksh

in Kunwar (September).

The more ambitious members of the caste abjure all flesh 5. Social and liquor, and wear the sacred thread. These will not p°^'^'°"- take cooked food even from a Brahman. Others do not observe these restrictions. Brahmans will usually take water from Sunars, especially from those who wear the sacred thread.

Owing to their association with the sacred metal gold, and the fact that they generally live in towns or large villages, and many of their members are well-to-do, the Sunars occupy a fairly high position, ranking equal with, or above the cultivating castes. But, as already stated, the goldsmith was a village menial in the Maratha villages, and Sir D. Ibbetson thinks that the Jat really considers the Sunar to be distinctly inferior to himself. The Sunar makes all kinds of ornaments of gold and f^^.fy^g^of silver, being usually supplied with the metal by his ornaments.

customers. He is paid according to the weight of metal

used, the rate varying from four annas to two rupees with an

average of a rupee per tola weight of metal for gold, and from

one to two annas per tola weight of silver/ The lowness of

these rates is astonishing when compared with those charged

by European jewellers, being less than lo per cent on the

value of the metal for quite delicate ornaments.

The reason is partly that ornaments are widely regarded as a means for the safe keeping of money, and to spend a large sum on the goldsmith's labour would defeat this end, as it would be lost on the reconversion of the ornaments into cash. Articles of elaborate workmanship are also easily injured when worn by women who have to labour in the fields or at home.

These considerations have probably retarded the development

of the goldsmith's art, except in a few isolated localities

where it may have had the patronage of native courts, and

they account for the often clumsy form and workmanship of

his ornaments. The value set on the products of skilled

artisans in early times is nevertheless shown by the statement

in M'Crindle's A7icient India that any one who caused an

artisan to lose the use of an eye or a hand was put to death."

In England the jeweller's profit on his wares is from 33 to 50

per cent or more, in which, of course, allowance is made for

the large amount of capital locked up in them and the time

they may remain on his hands.

But the difference in rates is nevertheless striking, and allowance must be made for it in considering the bad reputation which the Sunar has for mixing alloy with the metal. Gold ornaments are simply hammered or punched into shape or rudely engraved, and are practically never cast or moulded. They are often made hollow from thin plate or leaf, the interior being filled up with lac.

Silver ones are commonly cast in Saugor and Jubbulpore, but rarely elsewhere. The Sunar's trade appears now to be fairly prosperous, but during the famines it was greatly depressed and many members of the caste took to other occupations. Many Sunars make small articles of brass, such as chains, bells and little boxes. Others have become cultivators and drive the 1 Monograph on the Gold and Silver- rupee's weight, or two-fifths of an ounce. ware of the Central Provinces (Mr. '^ Journal of Indian A)i,]\.\\y i^og, 11. Nunn, I.C.S.), 1904. The tola is a p. 172.

plough themselves, a practice which has the effect of spoiling their hands, and also prevents them from giving their sons a proper training. To be a good Sunar the hands must be trained from early youth to acquire the necessary delicacy of touch. The Sunar's son sits all day with his father watching him work and handling the ornaments. Formerly the Sunar never touched a plough. Like the Pekin ivory painter

From early dawn he works ;

And all day long", and when night comes the lamp Lights up his studious forehead and thin hands. As already stated, the Sunar obtains some social distinc- 7. The tion from working in gold, which is a very sacred metal with o^'g^jlf the Hindus. Gold ornaments must not on this account be worn below the waist, as to do so would be considered an indignity to the holy material, Maratha and Khedawal l^rahman women will not have ornaments for the head and arms of any baser metal than gold. If they cannot afford gold bracelets they wear only glass ones. Other castes should, if they can afford it, wear only gold on the head. And at any rate the nose-ring and small earrings in the upper ear should be of gold if worn at all. When a man is at the point of death, a little gold, Ganges water, and a leaf of the tnlsi or basil plant are placed in his mouth, so that these sacred articles may accompany him to the other world. So valuable as a means of securing a pure death is the presence of gold in the mouth that some castes have small pieces inserted into a couple of their upper teeth, in order that wherever and whenever they may die, the gold may be present to purify them.^ A similar idea was prevalent in Europe.

Auruni potabile'^" or drinkable gold was a favourite nostrum of the Middle Ages, because gold being perfect should produce perfect health ; and patients when in extremis were commonly given water in which gold had been washed. And the belief is referred to by Shakespeare : Therefore, thou best of gold art worst of gold : Other, less fine in carat, is more precious.

Preserving life in medicine potable.-' ^ From a monograph on rural - Lang, Myth, Ritual atid Religion, customs in Saugor, by Major W. D. i. p. 98. Sutherland, LM.S. '^ 2 King Henry IV. Act IV. Sc. 4.

8. Ornaments. The marriage ornaments. The metals which are used for currency, gold, silver and copper, are all held sacred by the Hindus, and this is easily explained on the grounds of their intrinsic value and their potency when employed as coin. It may be noted that when the nickel anna coinage was introduced, it was held in some localities that the coins could not be presented at temples as this metal was not sacred.

It can scarcely also be doubted in view of this feeling that the wearing of both gold and silver in ornaments is considered to have a protective magical effect, like that attributed to charms and amulets. And the suggestion has been made that this was the object with which all ornaments were originally worn. Professor Robertson Smith remarks : ^ " Jewels, too, such as women wore in the sanctuary, had a sacred character ; the Syriac word for an earring is d ddsha, ' the holy thing,' and generally speaking, jewels serve as amulets. As such they are mainly worn to protect the chief organs of action (the hands and feet), but especially the orifices of the body, as earrings ; nose-rings hanging over the mouth ; jewels on the forehead hanging down and protecting the eyes." The precious metals, as has been seen, are usually sacred among primitive people, and when made into ornaments they have the same sanctity and protective virtue as jewels.

The subject has been treated ^ with great fullness of detail by Sir J. Campbell, and the different ornaments worn by Hindu women of the Central Provinces point to the same conclusion. The bindia or head ornament of a Maratha Brahman woman consists of two chains of silver or gold and in the centre an image of a cobra erect. This is Shesh-Nag, the sacred snake, who spreads his hood over all the lingas of Mahadeo and is placed on the woman's head to guard her in the same way.

The Kurmis and other castes do not have Shesh-Nag, but instead the centre of the bindia consists of an ornament known as bija, which represents the custard-apple, the sacred fruit of Sita. The nathni or nose-ring, which was formerly confined to highcaste women, represents the sun and moon. The large hoop circle is the sun, and underneath in the part below

- Religion of the Semites, note B.,

P- 453- - Bontlniy Gazetteer, Poona,Ki^'^. D., Ornaments.

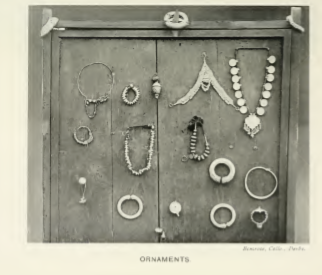

LIST OF ORNAMENTS, FROM LEFT TO RIGHT. Three bracelets on top of board, from left to right :— 1.—Anklet with links like coils of a snake. 2. Torn, or solid anklet. 3. Naugrihi, or wristlet of nine planets. Second row, from left to right :— 4. —Large nathni, or nose-ring. 5.—Another nangrihi. 6. BTja, or custard apple worn on head above biiuiia. 7. Biiuiia, or ornament worn on head. 8. — Hamel, or necklace of rupees with betel-leaf pendant. Third row, from left to right : — 9.—Small nathni, or nose-ring. -10. Bora, or waistband with beads like smallpox postules. 11. Kantha, or gold necklace. 12. Bohta, or circlet for upper arm. 13. Hasli, or necklet like collar-bone. Fourth row, from left to right : — 14. Karaiiphul, or earring like marigold. 15. Paijan, or hollow tinkling anklet. 16. Dhara, or earring like shield. 17.—Another anklet. 18.—Another armlet, called koparbeUi."

I

the nose is a small segment, which is the crescent moon and is hidden when the ornament is in wear. On the front side of this are red stones, representing the sun, and on the underside white ones for the moon. The nathni has some mysterious connection with a woman's virtue, and to take off her nose-ring — nathni utarna—signifies to dishonour a woman (Platts). In northern India women wear the nosering very large and sometimes cover it with a piece of cloth to guard it from view or keep it in parda. It is possible that the practice of Hindu husbands of cutting off the nose of a wife detected in adultery has some similar association, and is partly intended to prevent her from again wearing a nose-ring. The toe ornament of a high-caste woman is called hichJiia and it represents a scorpion {bicJihii).

A ring on the big toe stands for the scorpion's head, a silver chain across the foot ending in another ring on the little toe is his body, and three rings with high projecting knobs on the middle toes are the joints of his tail folded back. It is of course supposed that the ornament protects the feet from scorpion bites. These three ornaments, the bindia^ the nathni and the bicJiJiia, must form part of the Sohag or wedding dowry of every high-caste Hindu girl in the northern Districts, and she cannot be married without them. But if the family is poor a laong or gold stud to be worn in the nose may be substituted for the nose-ring.

This stud, as its name indicates, is in the form of a clove, which is sacred food and is eaten on fast-days. Burning cloves are often used to brand children for cold ; a fresh one being employed for each mark. A widow may not wear any of these ornaments ; she is always impure, being perpetually haunted by the ghost of her dead husband, and they could thus be of no advantage to her ; while, on the other hand, her wearing them would probably be considered a kind of sacrilege or pollution of the holy ornaments.

In the Maratha Districts an essential feature of a wedding 9. Beads

is the hanging of the mansral-sutrani or necklace of black '" °^^^\

!=> o t> ornaments.

beads round the bride's neck. All beads which shine and

reflect the light are considered to be efficacious in averting

the evil eye, and a peculiar virtue, Sir J. Campbell states,

attaches to black beads. A woman wears the mammal•

sutram or marriage string of beads all her life, and considers

that her husband's life is to some extent bound up in

it. If she breaks the thread she will not say ' my thread

is broken/ but ' my thread has increased '

- and she will not

let her husband see her until she has got a new thread, as she thinks that to do so would cause his death. The many necklaces of beads worn by the primitive tribes and the strings of blue beads tied round the necks of oxen and ponies have the same end in view.

A similar belief was probably partly responsible for the value set on precious stones as ornaments, and especially on diamonds, which sparkle most of all. The pearl is very sacred among the Hindus, and Madrasis put a pearl into the mouth at the time of death instead of gold. Partly at least for this purpose pearls are worn set in a ring of gold in the ear, so that they may be available at need. Coral is also highly esteemed as an amulet, largely because it is supposed to change colour. The coral given to babies to suck may have been intended to render the soft and swollen gums at teething hard like the hard red stone.

Another favourite shape for beads of gold is that of grains of rice, rice being a sacred grain. The gold ornament called kantha worn on the neck has carvings of the flowers of the singdra or waternut. This is a holy plant, the eating of which on fast-days gives purity. Hence women think that water thrown over the carved flowers of the ornament when bathing will have greater virtue to purify their bodies. Another favourite ornament is the hamel or necklace of rupees.

The sanctity of coined metal would probably be increased by the royal image and superscription and also by its virtue as currency. Mr. Nunn states that gold mohur coins are still made solely for the purpose of ornament, being commonly engraved with the formula of belief of Islam and worn by Muhammadans as a charm. Suspended to the hamel or necklace of rupees in front is a silver pendant in the shape of a betel-leaf, this leaf being very efficacious in magic ; and on this is carved either the image of Hanuman, the god of strength, or a peacock's feather as a symbol of Kartikeya, the god of war. The silver bar necklet known as Jiasli is intended to resemble the collar-bone.

Children carried in their mother's

cloth arc liable to be jarred and shaken against her body, so that the collar-bone is bruised and becomes painful. It is thought that the wearing of a silver collar-bone will prevent this, just as silver eyes are offered in smallpox to protect the sufferer's eyes and a silver wire to save his throat from being choked. Little children sometimes have round the waist a band of silver beads which is called bora ; these beads are meant to resemble the smallpox pustules and the bora protects the wearer from smallpox.

There are usually 84 beads, this number being lucky among the Hindus. At her wedding a Hindu bride must wear a wristlet of nine little cones of silver like the kalas or pinnacle of a temple. This is called nau-graJia or naic-giri and represents the nine planets which are worshipped at weddings—that is, the sun, moon and the five planets, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus and Saturn, which were known to the ancients and gave their names to the days of the week in many of the Aryan languages ; while the remaining two are said to have been Rahu and Ketu, the nodes of the moon and the demons which cause eclipses.

The bonJita or bdnkra, the rigid circular bangle on the upper arm, is supposed to make a woman's arm stronger by the pressure exercised on the veins and muscles. Circular ornaments worn on the legs similarly strengthen them and prevent a woman from getting stiffness or pins and needles in her legs after long squatting on the ground. The c/iutka, a large silver ring worn by men on the big toe, is believed to attract to itself the ends of all the veins and ligaments from the navel downwards, and hold them all braced in their proper position, thus preventing rupture.

On their feet children and young girls wear the paijnn

or hollow anklet with tinkling balls inside. But when a

married woman has had two or three children she leaves off

the paijan and wears a solid anklet like the tora or kasa.

It is now said that the reason why girls wear sounding

anklets is that their whereabouts may be known and they

may be prevented from getting into mischief in dark corners.

But the real reason was probably that they served as spirit

scarers, which they would do in effect by frightening away

snakes, scorpions and noxious insects ; for it is clear that

the bites of such reptiles and insects, which often escape unseen, must be largely responsible for the vast imaginative fabric of the belief in evil spirits, just as Professor Robertson Smith demonstrates that the jins or genii of Arabia were really wild animals.^ In India, owing to the early age of marriage and the superstitious maltreatment of women at child-birth, the mortality among girls at this period is very high ; and the Hindus, ignorant of the true causes, probably consider them especially susceptible to the attacks of evil spirits,

lo. Ear- Before treating of ear-ornaments it will be convenient piercmg.

^^ mention briefly the custom of ear-piercing. This is universal among Hindus and Muhammadans, both male and female, and the operation is often performed by the Sunar. The lower Hindu castes and the Gonds consider piercing the ears to be the mark of admission to the caste community. It is done when the child is four or five years old, and till then he or she is not considered to be a member of the caste and may consequently take food from anybody.

The Raj-Gonds will not have the ears of their children pierced by any one but a Sunar ; and for this they give him stdha or a seer ^ of wheat, a seer of rice and an anna. Hindus employ a Sunar when one is available, but if not, an old man of the family may act. After the piercing a peacock's feather or some stalks of grass or straw are put in to keep the hole open and enlarge it.

A Hindu girl has her ear pierced in five places, three being in the upper ear, one in the lobe and one in the small flap over the orifice. Muhammadans make a large number of holes all down the ear and in each of these they place a gold or silver ring, so that the ears are dragged down by the weight. Similarly their women will have ten or fifteen bangles on the legs.

The Hindus also have this custom in Bhopal, but if they do it in the Central Provinces they are chaffed with having become Muhammadans, In the upper ear Hindu women have an ornament in the shape of the genda or marigold, a sacred flower which is offered to all the deities. The holes in the upper and middle ear are only large enough to contain a small ring, but that in the lobe ' Religion of the Semites, Lecture III. ^2 lbs.

is greatly distended among the lower castes.

The tarkhi or Gond ear-ornament consists of a glass plate fixed on to a stem of auibari fibre nearly an inch thick, which passes through the lobe. As a consequence the lower rim is a thin pendulous strip of flesh, very liable to get torn. But to have the hole torn open is one of the worst social mishaps which can happen to a woman.

She is immediately put out of caste for a long period, and only readmitted after severe penalties, equivalent to those inflicted for getting vermin in a wound. When a woman gets her ear torn she sits weeping in her house and refuses to be comforted. At the ceremony of readmission a Sunar is sometimes called in who stitches up the ear with silver thread.' Low-caste Hindu and Gond women often wear a large circular embossed silver ornament over the ear which is known as dhara or shield and is in the shape of an Indian shield.

This is secured by chains to the hair and apparently affords some support to the lower part of the ear, which it also covers. Its object seems to be to shield and protect the lobe, which is so vulnerable in a woman, and hence the name. A similar ornament worn in Bengal is known as dJienri and consists of a shield-shaped disk of gold, worn on the lobe of the ear, sometimes with and sometimes without a pendant.^

The character of the special significance which apparently n. Origin attaches to the custom of ear-piercing is obscure. Dr. Jevons considers that it is merely a relic of the practice of shedding the blood of different parts of the body as an offering to the deity, and analogous to the various methods of self- mutilation, flagellation and gashing of the flesh, whose common origin is ascribed to the same custom. " To commend themselves and their prayers the Quiches pierced their ears and gashed their arms and offered the sacrifice of their blood to their gods.

The practice of drawing blood from the ears is said by Bastian to be common in the Orient ; and Lippert conjectures that the marks left in the ears were valued as visible and permanent indications that ^ From a paper on Caste Panchayats, ^ Rajendra Lai Mitra, InJo-Aiyans, by the Rev. Failbus, C.IVI.S. Mission, vol. i. p. 231. Mandla. VOL. IV 2 M of earpiercing.

12. Ornaments worn as amulets. the person possessing them was under the protection of the god with whom the worshipper had united himself by his blood offering. In that case earrings were originally designed, not for ornament, but to keep open and therefore permanently visible the marks of former worship.

The marks or scars left on legs or arms from which blood had been drawn were probably the origin of tattooing, as has occurred to various anthropologists." ^ This explanation, while it may account for the general custom of ear-piercing, does not explain the special guilt imputed by the Hindus to getting the lobe of the ear torn. Apparently the penalty is not imposed for the tearing of the upper part of the ear, and it is not known whether men are held liable as well as women ; but as large holes are not made in the upper ear at all, nor by men in the lobe, such cases would very seldom occur.

The suggestion may be made as a speculation that the continuous distension of the lobe of the ear by women and the large hole produced is supposed to have some sympathetic effect in opening the womb and making child-birth more easy. The tearing of the ear might then be considered to render the women incapable of bearing a child, and the penalties attached to it would be sufficiently explained. The above account of the ornaments of a Hindu woman is sufficient to show that her profuse display of them is not to be attributed, as is often supposed, to the mere desire for adornment.

Each ornament originally played its part in protecting some limb or feature from various dangers of the seen or unseen world. And though the reasons which led to their adoption have now been to a large extent forgotten and the ornaments are valued for themselves, the shape and character remain to show their real significance. Women as being weaker and less accustomed to mix in society are naturally more superstitious and fearful of the machinations of spirits. And the same argument applies in greater degree to children. The Hindus have probably recognised that children are very delicate and succumb easily to disease, and they could scarcely fail to have done so when statistics show that about a quarter of all the babies born in India die in the first year of age. But they do not ^ Introdtiction to the History of Religion, 3rd ed. p. 172.

attribute the mortality to its real causes of congenital weakness

arising from the immaturity of the parents, insanitary

treatment at and after birth, unsuitable food, and the general

frailty of the undeveloped organism. They ascribe the loss

of their offspring solely to the machinations of jealous deities

and evil spirits, and the envy and admiration of other

people, especially childless women and witches, who cast

the evil eye upon them. And in order to guard against

these dangers their bodies are decorated with amulets and

ornaments as a means of protection. But the result is

quite other than that intended, and the ornaments which are

meant to protect the children from the imaginary terrors of

the evil eye, in reality merely serve as a whet to illicit

cupidity, and expose them a rich, defenceless prey to the

violence of the murderer and the thief.

The Audhia Sunars usually work in bell-metal, an alloy 13. Audhia of copper or tin and pewter. When used for ornaments the ^""^'^• proportion of tin or pewter is increased so as to make them of a light colour, resembling silver as far as may be. Women of the higher castes may wear bell-metal ornaments only on their ankles and feet, and Maratha and Khedawal Brahmans may not wear them at all.

In consequence of having adopted this derogatory occupation, as it is considered, the Audhia Sunars are looked down on by the rest of the caste. They travel about to the different village markets carrying their wares on ponies ; among these, perhaps, the favourite ornament is the kara or curved bar anklets, which the Audhia works on to the purchaser's feet for her, forcing them over the heels with a piece of iron like a shoe-horn. The process takes time and is often painful, the skin being rasped by the iron.

The woman is supported by a friend as her foot is held up behind, and is sometimes reduced to cries and tears. High-caste women do not much affect the kara as they object to having their foot grasped by the Sunar. They wear instead a chain anklet which they can work on themselves. The Sunars set precious stones in ornaments, and this is also done by a class of persons called Jadia, who do not appear to be a caste. Another body of persons accessory to the trade are the Niarias, who take the ashes and sweepings from the goldsmith's shop, paying a sum of

ten or twenty rupees annually for them.^ They wash away the refuse and separate the grains of gold and silver, which they sell back to the Sunars.

Niaria also appears to be an occupational term, and not a caste. 14. The Formerly Sunars were employed for counting and testing n"o"fe-^^ money in the public treasuries, and in this capacity they changer. wcre designated as Potdar and Saraf or Shroff. Before the introduction of the standard English coinage the moneychanger's business was important and profitable, as the rupee varied over different parts of the country exactly as grain measures do now. Thus the Pondicherry rupee was worth 26 annas, while the Gujarat rupee would not fetch \2\ annas' in the bazar. In Bengal,^ at the beginning of the nineteenth century, people who wished to make purchases had first to exchange their rupees for cowries.

The Potdar carried his cowries to market in the morning on a bullock, and gave 5760 cowries for a new kalddr or English rupee, while he took 5920 cowries in exchange for a rupee when his customers wanted silver back in the evening to take away with them. The profit on the kalddr rupee was thus one thirty-sixth on the two transactions, while all old rupees, and every kind of rupee but the kaldm', paid various rates of exchange or batta^ according to the will of the moneychangers, who made a higher profit on all other kinds of money than the kalddr.

They therefore resisted the general introduction of these rupees as long as possible, and when this failed they hit on a device of marking the rupees with a stamp, under pretext of ascertaining whether they were true or false ; after which the rupee was not exchangeable without paying an additional batta, and became as valuable to the money-changers as if it were foreign coin. As justification for their action they pretended to the people that the marks would enable those who had received the rupees to have them changed should any other dealer refuse them, and the necessities of the poor compelled them to agree to any batta or exchange rather than suffer delay. This was apparently the origin of the ' Shroff-marked rupees,' familiar to readers of the Treasury Manual; and the line in a Bhat song, 'The ^ Monograph, loc. cit.

'^ This account is taken from Buchanan's Eastern India, vol. ii. p. lOO.

English have made current the kaldar (milled) rupee,' is thus seen to be no empty praise. As the bulk of the capital of the poorer classes is 15. Maihoarded in the shape of gold and silver ornaments, these are practices of ^ ° lower-class regularly pledged when ready money is needed, and the Sunars. Sunar often acts as a pawnbroker.

In this capacity he too often degenerates into a receiver of stolen property, and Mr. Nunn suggested that his proceedings should be supervised by license. Generally, the Sunar is suspected of making an illicit profit by mixing alloy with the metal entrusted to him by his customers, and some bitter sayings are current about him. One of his customs is to filch a little gold from his mother and sister on the last day of Shrawan (July) and make it into a luck-penny.^ This has given rise to the saying, * The Sunar will not respect even his mother's gold '

- but the implication appears to be unjust.

Another saying is :

' Sona Sunar kd, abJiarmi sansdr ka^ or, ' The ornament is the customer's, but the gold remains with the Sunar.' - Gold is usually melted in the employer's presence, who, to guard against fraud, keeps a small piece of the metal called cJidsni or indslo, that is a sample, and when the ornament is ready sends it with the sample to an assayer or CJioksJii who, by rubbing them on a touchstone, tells whether the gold in the sample and the ornament is of the same quality. Further, the employer either himself sits near the Sunar while the ornament is being made or sends one of his family to watch.

In spite of these precautions the Sunar seldom fails to filch some of the gold while the spy's attention is distracted by the prattling of the parrot, by the coquetting of a handsomely dressed young woman of the family or by some organised mishap in the inner rooms among the women of the house.^ One of his favourite practices is to substitute copper for gold in the interior, and this he has the best chance of doing with the marriage ornaments, as many people consider it unlucky to weigh or test the quality of these."* The account must, however, be taken to apply only to the small artisans, ^ Bombay Gazettee?; vol. xii. p. 71. ' Bombay Gazetteer, Hindus of Gujarat, pp. 199, 200.

^ Temple and Fallon's Hindustani * Pandian's Indian Village Folk, Proverbs. P- 41-

and well-to-do reputable Sunars would be above such practices. The goldsmith's industry has hitherto not been affected to any serious extent by the competition of imported goods, and except during periods of agricultural depression the Sunar continues to prosper.

A Persian couplet said by a lover to his mistress is, ' Gold has no scent and in the scent of flowers there is no gold ; but thou both art gold and hast scent.'

Sonar/Sunar

(From People of India/ National Series Volume VIII. Readers who wish to share additional information/ photographs may please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.)

Synonyms: Swarnakar [Bihar and/or Jharkhand] Hamkar, Potdar, Saraf, Soni, Swarnakar [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Sonari, Sonari Bania [Orissa] Jargar, Maipotra, Sawrnakar, Suniar, Verma [Chandigarh] Groups/subgroups: Ayodhyabasi, Ayodhyapuri, Barhaiya, Jathere, Jothara, Kammarkala, Kannaujia, Magahiya, Tetulia [Bihar and/or Jharkhand] Asdialohi [Orissa] Bagge, Bagri, Bahar, Bari, Bunjahi, Delhi, Desi, Dhalla, Dharna, Dhuna, Gharwal, Gujarat, Jaura, Kakal in Eastern plain, Khati, Mair, Masau, Multan, Nabha, Nichal, Pajji, Patni, PlaudRajputana, Shin, Tank [HA. Rose] Kanaujiya in Behar [H.H. Risley] Ajudhyabasi, Bagri, Chaahi, Deswali, Kanaujiya, Khati, Mair, Rastogi in North West Province [W. Crooke] Titles: Surnames: Gupta, Sonar [Bihar and/or Jharkhand] Soni, Swarnakar [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Charan, Gaikwad (place name), Jagdal (place name), More, Rajgarh (place name) [Maharashtra] Mahapatra, Pusthi, Sahoo, Chinera, Sahu, Saraf, Sathua, Senapari [Orissa] Exogamous divisions: Ahir, Ajhra, Aksali, Oasiputra, Deshi (Devangan), Jain, Kadu, Kanade, Khandeshi, Konkan and Karnatak, Konkani, Lad, Malwi, Maratha, Pardeshi, Sada, Shiivant, Vaishya, Vidur in Deccan [R.E. Enthoven] Exogamous units/clans: Kaushal, Mudgal [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Exogamous units/clans (gotra): Handa, Kaplash, Mehta, Saul, Soni, Varma [Himachal Pradesh] Bharadwaj, Chanda, Mayur (peacock), Nageswar (snake) [Orissa] Gotra: Kashyap [Bihar and/or Jharkhand] Garg, Goutam, Kashyap, Sandilya [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Agasthya, Bhagavat, Bharadwaj, Jamadagni, Koundinya, Vishwamitra [Maharashtra] Bharadwaj [Orissa] Angirasa, Atri, Bharadwaj, Bhargav, Dadhichi, Goutam, Jamadagni, Kashyap, Koundinya, Parasar, Sandilya, Sankhayana, Vasisht, Vatsa, Vishwamitra [R.E. Enthoven]

Sunar

Groups/subgroups: Ayodhyawasi, Baghelkhandi, Bundelkhandi, Medhkshatri, Purania [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Awadhia, Ayodhyabasia, Bais, Bhojpuria, Gaur, Kamarkalla, Kanaujia, Mair, Oria in Bengal [H.H. Risley] Ahir, Kadu, Lad, Malvi, Panchal, Vaisya in Hyderabad [S.S. Hassan]

- Sub-divisions: Ahir Sunars, Audhia, Bundelkhandi, Lad, Mair, Malwi, Pandhare, Patkars, Purania [Russell & Hiralal]

Titles: Setti [E. Thurston] Chaudhri, Poddar, Sahu [H.H. Risley] Surnames: Swarnkar, Soni [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh]

- Exogamous septs/bainks: Bhilsainya, Diliwal, Kalpiwal, Kanaujia, Kolhimare, Ladaiya, Munde, Narwria, Kale

[Russell & Hiralal] Gotra: Bharadwaj, Gautam, Kashyap, Kaushal, Sandilya [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh]

- Sections: Ainia, Aminapur, Ampur, Anril, Antaiya, Asarhi, Aswaria, Bagaiya, Baguan, Barmait, Barni, Bathuet,

Belha, Bhaunrajpuri, Bhekh, Bhuswal, Bibarhia, Bihar and/or Jharkhandi, Bilar, Borha, Chalhaka, Chitha Dhakaichha, Dhaundria, Dubaithia, Dumrahar, Fatehpuri, Gancsia, Ganet, Garahia, Gehanl, Hamdabadi, Hanuman, Hardiwal, Jakhalpuria, Jamalpuri, Janakpuri, Josiam, Karbhaia, Kashyap, Kasi Kastuar, Katalpuri, Kerauta, Kokarsa, Kothadomar, Lohatia, Machhilha, Machi, Makundpuri, Marj, Mirchwan, Musamia, Noinjora, Pachpakar, Parian, Proha, Rajgrihi, Rampuri, Rautar, Saharwar Sakaddi, Samundar Khora, Silaichia, Simar, Sisodia, Sochari, Sonpuria, Sultanpuria, Tejania, Teliha in Behar [H.H. Risley] Ahstikar, Ambegaonkar, Chilkharkar, Dahale, Halikar, Jinturkar, Kulthe, Lolage, Moregaonkar, Nagarkar, Patharkar, Pedgaonkar, Rajurkar, Shahane, Shingnapurkar, Tak, Tehare Udawant Udekar in Hyderabad [S.S. Hassan]

Notes

In Bengal this caste has broken up into so many divisions that it has become almost imposssble to distinguish the minute shades of difference between them. It is allied to the great Bania tribe, and claims to be descended from Vaisya parents, although now degraded, and not included in the nine clean Sudra castes. One authority1 describes them as the offspring of a Baidya and a Vaisya female; while another2 connects them with the issue of a Brahman and a Vaisya woman, and therefore the same as the Parasava, or mixed order, of Menu. Among the Marhattas Sonars claim to be Upa-Brahmanas, or minor Brahmans.

The Bengal Sonars ascribe their low position to the enmity of Ballal Sen, who ordered them to eat with Sudras, which they refused to do. The incensed monarch appointed spies to watch them, who invented a story that the caste Brahman having accepted a present from a low caste man sold it to the Sonars. The Rajah on hearing the false charge, and without making any inquiry, issued an order degrading the whole caste.

It is much more probable, however, that Sonars are Hindustani Banias, who, losing rank by residing in Bengal, were placed in an inferior position when the re-organisation of Hinddu society was effecte.

The total number of Sonar-baniks in Bengal is 60,366, of whom 12,735, or one-fifth, inhabit Burdwan, 8,195 the twenty-four Pergunnahs, 8,097 Hughli, and 292 Dacca. They diminish in numbers on the east of the Ganges; and it would seem from this that they originally settled in the central, and more peaceful, districts.

In eastern Bengal the Sonar-banik caste has four subdivisions, namely:�

They claim to be descendants of Sonars resident in Bengal during the reign of Ballal Sen, and are undoubtedly the oldest branch of the family. Two Sreni are met with, Kulina and Varendra, or Maulika, inferior, which never intermarry. Every Maulika, however, asserts that he is a Kulina, and village Sonars, by assuming similar claims, cause endless squabbles and feuds. Ward distinguishes between the Sauvarna-kar and the Sauvarna-banik; the former being goldsmiths.

The latter money-changers. It is remarkable that members of the Banga engaging in the caste profession of goldsmiths are styled Sankara, or mixed, baniks, and excommunicated from the society of their brethren. In the city about forty families reside, twenty-five of whom belong to the pure town stock, and fifteen to the Grami, or rural. These two branches are still farther sundered by haying two distinct Dals, or unions.

The Bangas have three gotras, Kasyapa, Gautama, and Vyasa. The "Padavi," or titles, are�

The marriage ceremonies are copied from those observed at the wedding of Sri Ramachandra and Sita, while in western Bengal the marriage service is that of Mahadeva and Parvati. At the former the bridal pair, seated on stools, are carried round the court; at the latter the bridegroom stands, while the bride is borne round him.

The bride wears a red dress, as well as a lofty diadem (Mukuta) with a red turban, from which tinsel pendants hang. The bridal attire becomes the perquisite of the barber; the dress worn on the second day falls to the Ghataka. The "Pradhan," or president of the caste assembly, is always a Kulina. The Kulina sometimes marries a Maulika girl when her dowry is large, but this alliance does not exalt her family.

The Banga Sonars are jewellers, but, as a rule, do not manufacture ornaments. They are often bankers, traders, and shopkeepers. The poorer class accept employment as writers, but would sooner starve than cultivate the soil The large majority are Vaishnavas, but a few follow the Tantric ritual.

1 Ward's "Hindus" i, 134.

2 Wilson's "Glossary," p. 488.

2.Dakhiin Rarhi Sonars

In the city reside about seventy families, who originally sought shelter in Eastern Bengal, along with the Uttar Rarhi and Nadiya Sonars, from the Marhatta invasion of 1741. Among them rage interminable disputes about precedence, and the confusion is increased by the "padavis" being the same as those of the Banga.

The houses of Nilambara Datta and Potiraj De are reckoned the first of Kulinas, and next, but at a great interval, are the children of two brothers, Chanda and Madhu, who are Sils, and reside at Balgonah, in Burdwan. Families with the titles of Boral, Laha, Chand, and Addi are deemed more aristocratic than the Maulika.

The gotras of this division are�

As a general rule the Dakhin Rarhi do not intermarry with the Uttar Rarhi, but take "Puri," or cake, from them, and even cooked food, if on friendly terms. The daughter of a Kulina marrying a Maulika bridegroom sinks to his level, but the daughter of a Maulika marrying a Kulina is raised to his. Dakhin Rarhi women dress like other Hindu females of Eastern Bengal; the Uttar Rarhi as women of Burdwan and Hughli.

The Dakhin Rarhi worship Lakshmi daily, when rice, sugar, and flowers are offered, and no woman will touch food until this duty is performed. The "goddess of wealth" is also worshipped with especial honour four times every year.

The members of this subdivision are usually employed as writers.

3.Uttar Rarhi Sonars

Many peculiarities of their earlier home are retained by this subdivision. The women still speak the Burdwan "Bhasha," or dialect, and their dress is that of Central Bengal. The gotras are many, and the following are the most important:�

The titles are the same as those of other Sonars, but they have no Maulika. Their president is styled "Murdhanya," a Sanskrit word for highest.

The Uttar Rarhi still prepares the marriage space, called Marocha, which has been given up by the Dakhin Rarhi, and the bride wears the lofty diadem, and appendages of the Banga.

In Dacca there are about seventy families, the men being employed as clerks, accountants, and bankers. Only four annual festivals in honour of Lakshmi are kept, that on the Diwali being omitted. Manasa Devi is propitiated with great ceremony, and on the Bhagiratha Dashara a branch of "Sij" (Euphorbia ligularia), sacred to the "goddess of snakes," is planted in the courtyard, and on every Panchami, or fifth lunar day of each fortnight up to the Dashara of the Durga Pujah, the Sonars make offerings to it. On the great day of the feast, the Vijaya Dasami, the plant is plucked up and thrown into the river.

4.Nadiya, or Sapta Grami, Sonars

This subdivision constitutes a small body numbering some thirty-five households. Driven from their former homes by the Marhattas, they crossed the Ganges, and settled in Dacca.

The principal gotras are�

The patronymics are Sil, Boral, Pal, Sena, Maulika, De, Hari Priya Das, and Karana Vari Das.

Being a small community the Nadiya Sonars intermarry with the Dakhan and Uttar Rarhi, and easily obtain wives by giving a large dowry.

While the Tak-sal, or Mint, was open at Dacca, the Nadiya Sonars worked as Son-dhoas, goldwashers, or Nyariyas, in fusing and purifying metals, but since its closure they have worked as Son-dhoas on their own account. The dust and refuse (Gad) of goldsmiths' shops are bought for a sum varying from eight anas to five rupees a ser, according to the amount, or nature of the business. The refuse being carefully washed the metallic particles in the sediment are transferred to shallow earthern pans and the larger separated by a skilled workman, or Karigar.

The smaller mixed with cowdung and a calx of lead form a ball, named Pindi, or Pera. This ball being placed in a hole partially filled with charcoal, fire is applied, and as the lead melts it carries with it all gold and silver filings, forming a mass, called "Lina." This "Lina" is then dissolved in a crucible, and the gold and silver being unmelted are easily separated.