Surat City

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

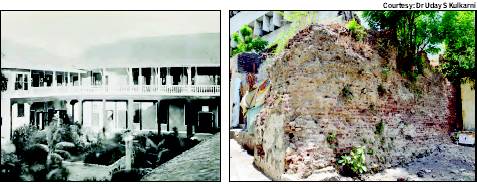

The first East India Company ‘factory’ in India

First English factory in India in ruins

Manimugdha S Sharma, TNN | Jun 17, 2013 |

In 1612, a maverick English sea captain, Thomas Best, sank four Portuguese galleons off the Surat coast with his two ships, Red Dragon and Hosiander. Captain Best and his crew's exploits in the naval Battle of Swally (corruption of Suvali) on October 28, 1612, impressed the Mughal governor of the province so much that he got them a treaty ratified by Emperor Jahangir, which translated to trading rights. By January 1613, the first East India Company factory had come up at Surat.

Four centuries later, those early footprints of the British Empire have been obliterated. There is no sign of the factory — more of a warehouse — save fragments of a wall that once belonged to the sprawling establishment. The ruins are a testimony to our indifference to heritage structures.

Of course, nobody could have imagined that the English would expand that first factory into another factory, that factory into a province, and that province into an empire in about 150 years. But at Surat in 1613, there were five principal factors — Andrew Starkey, Canning, Aldworth, Withington and Kerridge — who struggled hard to stay afloat in the face of Portuguese hostility, intrigues of the Portuguese Jesuits, and unfriendly behaviour of Mughal crown prince Mirza Khurram (later Emperor Shah Jahan).

Khurram, who had the jagir of Surat, favoured the Portuguese over any other European power, and so did the Surat Mahajan Sabha, a representative body of Indian traders. However, it was Khurram who gave Sir Thomas Roe the firman to trade in 1618 in the name of his father, Emperor Jahangir, after the English once again defeated the Portuguese fleet at Surat and proved their mastery over the seas.

According to historian H G Rawlinson, the factory was one of the best buildings in Surat and was leased to the company for £60 per annum. "It was a solid, two-storied building, opening in Muhammadan fashion, inwards. The outside was plain stone and timber, with good carving 'without representations'. The flat roof and the upper story floors were of solid cement, half a yard thick. Inside was a quadrangle surrounded by cloisters or verandahs. The ground floor was used for the Company's trade; the rooms opening on to it, utilised as stores and godowns, presented a busy scene in the shipping season..." he wrote in his 1920 book British Beginnings in Western India: 1579-1657; an account of the early days of the British factory of Surat.

The Times of India traced the English factory and found its location not far from the Surat fort. This fort was commissioned by Sultan Mahmud III — who was fed up with Portuguese attacks on the city — and built by an Ottoman officer named Safi Agha at a time when Mughal Emperor Humayun was in exile and the Pathans held sway in Delhi. The fort became Mughal when Emperor Akbar annexed the subah of Gujarat to his empire. But in 1759, the English occupied it. Subsequently, the Raj used the structure to house the revenue and police departments, in whose occupation it has remained.

The Surat Municipal Corporation (SMC), its offices located in a Mughal building called Mughal serai, is responsible for the fort but it's clearly in a complete mess right now. The corporation says on its website: "...such a great fortification built to provide the citizens of Surat with an adequate defence against the attacks of the invaders seems to have been forgotten from the minds of the present generation." SMC has also complicated matters by dumping all the silt and waste from the ongoing Hope Bridge expansion project inside the fort.

Historian Uday S Kulkarni visited the place last month and was struck by the lack of awareness about the importance of such heritage places there. "The rich history of the 500-year-old fort and the erstwhile English factory have been apparently forgotten; and what ought to be Grade A monuments are neglected by the Archaeological Survey of India and the civic administration. The Mughal serai is still a civic office and the British cemetery with tombs of historical personalities is poorly marked and attended," says Kulkarni.

Surat municipal commissioner M K Das squarely blames the degradation on encroachments. "Whatever anomalies you've seen have happened only in [May and June 2013] or so. We are trying to fix this. We've found out 150-year-old maps of the place and are trying to restore the fort scientifically," Das said.

A sliver of hope may be found in the three-part Chowk Bazaar Heritage Square project though, which is a plan to revamp the Tapi riverfront in Surat and all the heritage structures lying along it.

Diamond industry

‘Chitthi’ system

The Times of India, June 16, 2015

Surat diamantaires to discard ‘chitthi’ system

Melvyn Reggie Thomas

It's 5pm and Naresh Thummar, owner of a diamond polishing unit in Katargam, has struck a deal in the trading hub of Mahidharpura to sell his polished gems for Rs 3 crore. The trader hands him a small paper chit mentioning the size, carat, colour, purity, and, most importantly, the date by which Thummar will get his payment.

The paper chits, which are otherwise thrown into dustbins, have been an important trade instrument in the Rs 90,000 crore diamond industry for over six decades now. But, this 'chitthi system' that is based on mutual trust is set to be banished now.

Following an increase in defaults and cheating cases, the small and medium diamond unit owners are readying to embrace a more reliable system of 'jhangad', a kind of promissory note to arm fraud victims with stronger evidence for legal action. Since September 2014, defaults at least to the tune of Rs 500 crore have been reported in Surat.

Vallabh Borda, a diamantaire in Katargam, has stopped dealing through chithis after losing Rs 50 lakh to a trader. This trader duped 24 diamantaires of Rs 50 crore in January. "I prefer jhangad now. I face a lot of difficulties as many traders in the markets still follow the chit system. I don't want to lose money, especially when the market condition is not good these days," said Borda.

Dinesh Navadia, president of Surat Diamond Association (SDA), said, "We have already launched a campaign to persuade traders and manufacturers to adopt this fool-proof system. Some have switched over but many are expected to adopt in the next few months." Navadia said that all the units will adopt the new system over the next one year.

Arvind Pokia, a diamond unit owner in Varachha, said, "I have sought the help of SDA to guide me on using the jhangad system. My turnover is just Rs 150 crore and I can't afford to lose my diamonds and money to fly-by-night operators."

So precious are the paper chits that diamond unit owners keep them in 15 iron vaults in Varachha and Mahidharpura markets along with the gems. These markets witness diamond trade of nearly Rs 400 crore daily - all done through the chitthis.

"In the 1960s, the diamond industry evolved due to closely knit families of diamond polishers, traders and importers. As most of them knew each other, they traded only through chitthis. The tradition still continues," said Navadia.

None of the technological advances in the last six decades have replaced this system of payment that works on sheer faith.

Stent manufacturing

The Times of India, Jun 15 2015

Melvyn ReggieThomas

Diamond hub Surat is now a major player in the cardiac stent market. The city , famed for its Rs 90,000crore diamond industry , has emerged as the biggest manufacturer of cardiac stents in India. Nine of the 11 Indian companies manufacturing stents -tiny tubes that make blood flow through choked arteries -are based in Surat and neighbouring Vapi. There is a reason for it: the laser technology that revolutionized diamond cutting has been the lifeblood of the stent industry .

South Gujarat's companies have captured 30% market share in the Indian coronary stent mar ket, valued at over $400 million, roughly Rs 2,500 crore. Overall, Indian compa nies enjoy 40% share as foreign players are fast ceding ground due to pricing -domestic stents cost just half.

“We pioneered the use of laser in diamond cutting in 1992,“ said Ganesh Sabat, the chief executive officer of Sa hajanand Medical Technologies (SMT). The parent company , which still makes diamond cutting equipment, set up the arm for making stents in the year 2000. Its success, in a market which was entirely dependent on imports, brought in other players like Meril Life Sciences and Heart Beat Interventions who have made it big.

Cardiac stents are made of stainless steel or an alloy with co steel or an alloy with co balt and chromium. The process requires the sa me equipment and skill sets as diamonds. In fact, stent making requires mu-ch lesser intensity of laser fire than diamonds.

It requires a laser to drill a hole with a diameter of 2.25 to 4.5 mm and length of 8 to 48 mm. of 8 to 48 mm.

Ahmedabad-based cardiologist, Dr Sameer Dani, who has been using Surat-made stents for a decade, said: “Over the years, the quality of local stents has improved vastly .“

Dr Tejas Patel, a Padmashri awardee, said he only uses stents that are approved for use in the US and Europe.“But if low-cost stents made locally can assure long-term efficacy and quality , there is a huge market here,“ he said.

Swaminarayan temple

The Times of India, June 9, 2016

Authorities at a temple in Surat say they have been caught off-guard by the furore over an idol dressed up in the erstwhile R-S-S uniform of khaki shorts and a white shirt. The temple is dedicated to 19th-century spiritual leader Swaminarayan venerated by many as a divine incarnate. The issue came to light after a picture of Swaminarayan in the Sangh uniform — complete with a black cap and black shoes — went viral on social media. The idol is also seen holding the national flag in one hand.

Congress and BJP both expressed dismay at the move, even as a temple priest said it was part of a longstanding practice of dressing up the idol in different outfits. Priest Vishwaprakashji said the outfit was gifted by a local devotee a couple of days ago. "We do not have any other agenda. We did not know that it will create a controversy," he added.

Notwithstanding the temple's denial of having any intention to endorse the views of R-S-S, Congress member Shankersinh Vaghela said they must refrain from such activities. "What do you want to prove by dressing up god in khaki shorts? I pity those who have done that. This is very unfortunate," Vaghela added. Gujarat BJP chief Vijay Rupani also said it should not have been done. "I am really surprised. I don't approve of such actions," he said.