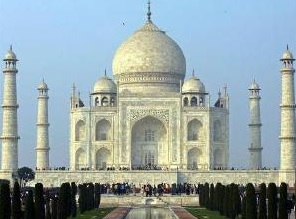

Taj Mahal, Agra

Agra: the Taj

Title and authorship of the original article(s)

|

A teardrop on the cheek of time By Dr Syed Amir, Dawn, 2006 |

This is a newspaper article selected for the excellence of its content. |

The celebrated Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore allegorically referred to the Taj Mahal in one of his verses as ‘one teardrop, glistening spotlessly bright on the cheek of time.’ Classified as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Taj is a testament to the eternal and enduring love of a man for his wife. It is visited by more than three millions tourists annually, up to 300,000 of them coming from outside India. In 1983, Unesco designated it a world heritage site.

More than three and half centuries have elapsed since the monument was built by Emperor Shah Jahan; however time has not been kind to this Islamic architectural masterpiece. Especially the decades since independence have witnessed a noticeable deterioration in its sparkling white appearance. In addition to the physical stress imposed by millions of visitors trudging on its delicate floors and through its spacious pavilions, atmospheric pollution and corrosive gases spewed by the iron foundries of Agra have inflicted major harm. Persistent exposure to pollutants in the air has dulled the brilliant shine of the porcelain-like marble, imparting a yellowish tinge to some sections of the facade.

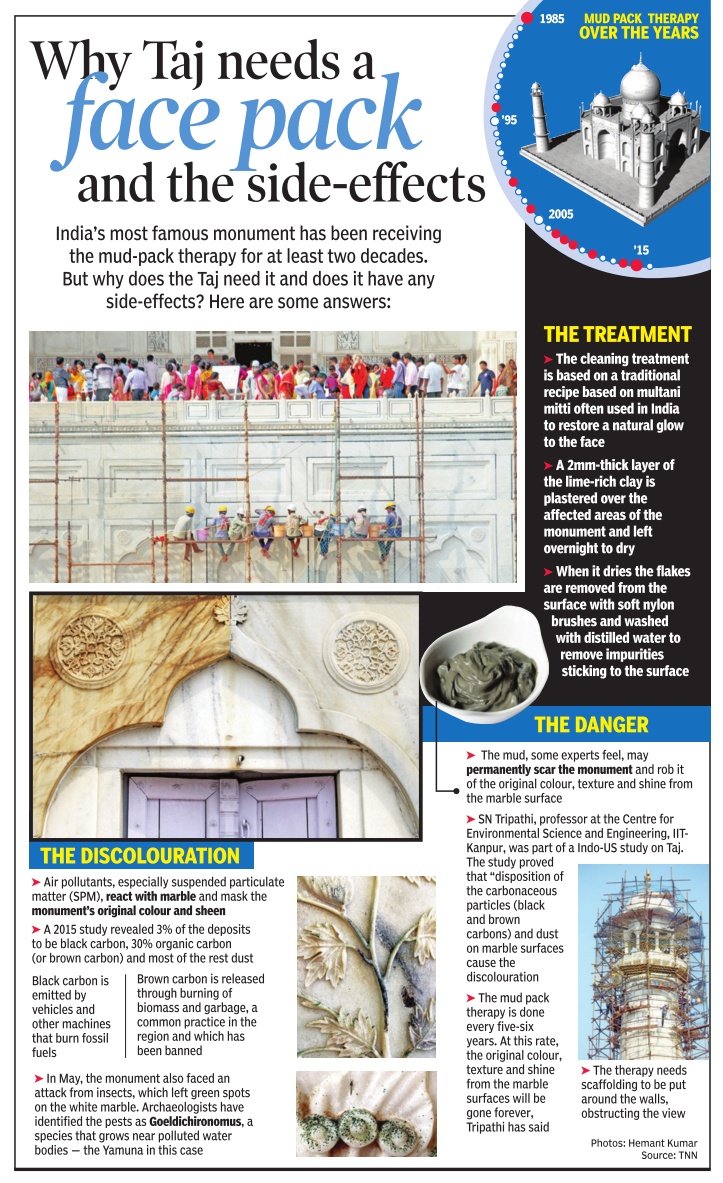

The government has been concerned about preserving the beauty and mystique of the Taj that has become a symbol of national pride and a source of much revenue. However, combating the menace of air pollution eating into the marble surface poses a challenge far greater than maintaining the structural soundness of the building. The Indian Supreme Court, more than 10 years ago, had decreed the closure of factories and industrial units in the proximity of the Taj in a desperate attempt to reduce the level of pollution and retard discoloration of the marble surfaces. The decree had only marginal success. After much experimentation, Indian scientists have now come up with an ingenious and inexpensive solution. Application of Fuller’s earth (locally known as Multani Mitti) has long been recommended by Unani and Ayurvedic physicians for facial and skin rejuvenation. Scientists have discovered that briefly applying a thin coat of this to the Taj’s exterior, and then washing it off, can effectively restore much of its original glitter. The natural substance has the ability to extract and absorb the impurities and pollutants that have become embedded in the marble over a period of time.

The Taj Mahal’s current problems are not entirely recent in origin. In a recently published book entitled Taj Mahal, authors Diana and Michael Preston narrate in exquisite detail the planning, construction and completion of the magnificent monuments and its subsequent deterioration. With the decline of Mughal power and the disintegration of the central authority in the 18th- and 19th-century India, the Taj suffered many acts of vandalism at the hands of unruly bands of Jats and Marathas. Its precious and semi-precious floral inlays were chiseled away; lavish carpets, expensive wall hangings and an ornate door made of silver were removed and carted away.

British suzerainty brought no relief. Once Agra was captured by General Lake in 1803, the Taj Mahal became a playground for soldiers and employees of the East India Company. They would use its marble floors and terraces for late night dancing parties, while the mosque and tasbih khana on the two sides of the tomb were rented out to newlyweds to be used as weekend cottages.

Lord William Bentinck who served as the Governor General, first of Bengal and then of India from 1828-1835, had a reputation for stinginess and little appreciation of India’s cultural heritage. He is reported to have contemplated demolishing the Taj and auctioning off the rubble to raise money. The plan was, however, abandoned as it was estimated that the cost of demolition would exceed the amount of cash that could be raised by sale of the marble slabs. Although the story is repeated in several chronicles, its authenticity has been disputed by Bentinck’s biographer, John Rosselli and it might be only apocryphal. Regardless, it does reflect how little appreciation of the monument existed at the time.

Scientists have discovered that briefly applying a thin coat of this [Multani mitti] to the Taj’s exterior, and then washing it off, can effectively restore much of its original glitter.

The Taj remained in a state of neglect and disrepair for many years. Its once lush gardens, attractive water fountains and luxuriant flower beds were all withering away. Its fortunes were reversed with the appointment at the turn of the century of Lord Curzon as the viceroy of India (1898-1905).

An aristocrat educated at Oxford and appointed to one of the most powerful positions in the world at the young age 39, Curzon was reputed to be a supercilious person with an exaggerated sense of superiority. Fortunately, he also had a deep interest in the preservation and restoration of historic buildings of the Mughal era, especially the Taj Mahal.

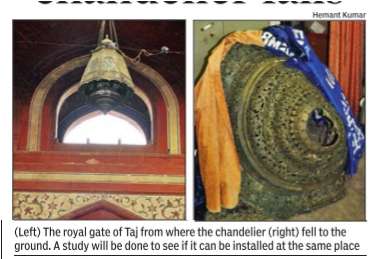

Soon after his arrival Lord Curzon initiated a major restoration project of the Taj which he cherished. The work continued even after he left India and was completed in 1908. He ordered the construction of a brass hanging lamp; a replica of an antique lantern which he had originally seen and much admired in a mosque in Cairo, Egypt. He gifted it to the Taj where it still hangs from the ceiling of the interior chamber above the cenotaph.

Lord Curzon was extremely proud of the contribution he had made to the restoration of the Taj. In his speech delivered from the plinth of Taj Mahal — one of the last ones he gave as viceroy and cited by Diana and Michael Preston in their book — he proudly announced: ‘If I’d never done anything else in India, I have written my name here and the letters are a living joy.’

It may not be widely known that this mausoleum at Agra is not the first resting place of the young queen Arjumand Banu Begum, popularly known as Mumtaz Mahal. Although Mumtaz Mahal was not Shah Jahan’s only wife, the relationship between the two had been exceptional. They had been intensely devoted to each other and the emperor never travelled without her by his side.

The Mughals had been battling the kingdoms of Deccan for several generations in an attempt to subdue them. On one such occasion in 1629, Shah Jahan left the capital for Burhanpur on the Tapti River in present-day Madhya Pradesh at the head of a mighty Mughal army to suppress a local insurgency. The city at the time served as the capital and military headquarter of the Mughal Empire in the South.

In the summer of 1631, Mumtaz Mahal, pregnant with her 14th child, went into labour at the royal palace at Burhanpur. She gave birth to a stillborn baby and died of resultant complications, while the distraught Princess Jahan Ara, her daughter, and Shah Jahan were at her side.

It has been recorded by chroniclers that the emperor went into a period of deep mourning following the death of his beloved wife; his beard reportedly turning grey in a matter of days. He never took serious interest in the conduct of the state business thereafter.

Mumtaz Mahal’s body was temporarily interred in a tomb at Burhanpur for about six months and later moved to Agra in a golden casket arriving at the capital in regal splendour. Today, it reposes in the monument built in her memory, so ethereal and majestic that it has had no rival. The Taj Mahal provided succor and comfort to Shah Jahan during the final nine years of his life which he spent as a prisoner at Agra Fort from where he was permitted to gaze at the Taj, but never to visit it.

Chandelier falls down

Source:

1. The Times of India, Aug 22, 2015

2. The Times of India, Aug 23 2015, Aditya Dev

Taj's British-era chandelier falls

ASI orders probe

A 60-kg British-era copper chandelier at the main entrance of 17th century Taj Mahal crashed down recently, prompting the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to initiate a probe into the matter. The six-feet high and four-feet wide chandelier, gifted by Lord Curzon and installed at the Royal Gate of Taj Mahal in 1905, fell down on August 19, 2015, sources said.

Conservation skills of ASI have come in doubt after a huge copper and bronze chandelier gifted by Lord Curzon in 1909 and hanging at the royal gate of the Taj Mahal fell on the ground, damaging it. Though tourists were milling around, no one was hurt. ASI officials now say they are looking to fix and reinstall it at the same place. According to an ASI official, the six-foot high and fourfoot wide chandelier was a gift from Curzon and installed at the royal gate. “It is believed that when Curzon visited Agra and Fatehpur Sikri in 1905, he ordered the installation of this chandelier. He also got a Dak Bangla built at Fatehpur Sikri Fort during that time,“ the official added.

ASI superintending archaeologist Bhuvan Vikrama said, “An inquiry is being done to know the cause of its fall. Anybody's involvement has already been ruled out and it seems the chandelier fell because of natural wear and tear. We will do a study to see if it can be rein stalled at the same place.“

“Curzon had great interest in ancient monuments and a lot of attention was given to preserve them during his time.It was during his time the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act was passed in 1904. A great attention should be given to preserve the relics,“ MK Pundhir, medieval archaeologist from the Centre of Advance Studies in History at Aligarh Muslim University , said.