1971 war: The Role of the Indian Navy

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

INS Vikrant

Evading-a Pakistani submarine

Ravi Sharma, Dec 8, 2021: The Times of India

The 1971 war was the first time that the Indian Navy was pressed into action, with it having been kept out of the loop during the 1965 Indo-Pak war due to some obscure fear of escalating the conflict. Our largest ship Vikrant was in fact undergoing repairs in a dry dock when war broke out in 1965. The Navy had been hurting ever since; in peacetime, the Armed Forces exercise regularly to be ready for war. When war comes, and if an arm is not assigned a role, then what is the purpose of that Arm? Pakistan naval ships in 1965 had fired a few shells at random on Dwarka port in Gujarat. The shells caused no damage, but Pakistan’s huge publicity of the attack made our Navy seem inept. Vice Admiral SM Nanda, who was then commanding the Western Naval Command, prophetically stated in a 1969 interview to the Bombay tabloid ‘Blitz’ that “…if war comes again, I assure you that we shall carry it right into the enemy’s biggest ports like Karachi”.

That assurance was fulfilled by the missile boat attack on Karachi two years later, and in fact spearheaded by Admiral Nanda, who was now Chief of Naval Staff. He insisted and succeeded in obtaining a major role for the Indian Navy in 1971. Despite the short operating range of our missile boats, innovative planning was devised for attacks on Karachi and Pakistan ships in the Arabian Sea, while a far more effective role was seen for Vikrant by deploying her off East Pakistan to provide support to our Army and attack coastal targets leaving the Air Force to focus on inland targets. The ships, led by Vikrant and its air surveillance, would bottle up the Bay of Bengal and prevent reinforcements of men and material either reaching or escaping East Pakistan.

Vikrant had been facing a persistent problem with a leak in one of her four boilers, but after repairs to the extent possible in Bombay, it was ordered to sail for the eastern coast to be ready for quick action if war was to be declared. Utmost secrecy was required to keep her movements concealed from Pakistan to preserve the element of surprise, as well as for Vikrant’s own safety as she was the main target for Pakistan’s Navy. For us, the carrier’s deployment off the east coast had an added advantage: only one Pak submarine, Ghazi, had the endurance to operate that far from its home base at Karachi.

Covering such a large ship’s tracks aren’t easy, however, and an elaborate plan was conceived to conceal Vikrant’s movements. Dummy signal traffic was generated from other locations to give the impression that the carrier was operating elsewhere. This was backed by other ruses: for example, with dummy signals indicating that Vikrant was near Cochin, food and other supplies purportedly to meet her demands were rushed to Cochin even though the carrier had already crossed over to the east.

Until 1971, our Navy had just one fleet based in Bombay. Admiral Nanda decided that for better control and coordination, there should be two fleets, Western and Eastern. Consequently, the Eastern Fleet was formed on 1 November 1971 with Vikrant as the flagship and a few other warships. Rear Admiral SH Sarma was appointed Eastern Fleet Commander and I, the Fleet Communications Officer on his operational staff. At that time, I was busy with my job as an instructor in Signal School, Cochin, and was unaware of these new developments. So when my boss, Commander ‘Clinker’ Karve, told me about my new appointment, I told him to quit playing April Fool 6 months late – or early for that matter – as there was no such thing as an Eastern Fleet! He had to show me the written orders to get me to start packing my bags for Vishakhapatnam (Vizag), which was designated as the base for the Eastern Fleet.

Admiral Sarma, along with his staff, embarked on Vikrant on 6 November by helicopter off Vizag and we sailed for Port Blair in the Andaman Islands. The Fleet eventually moved to the northernmost island, Port Cornwallis, to be within hours of striking distance at enemy shore targets. Throughout all this while, the Fleet followed a strict regime of radio discipline in order not to give away our position to Pakistan, which could intercept our radio communications and thus fix our location. No signals to shore authorities were made while at sea; instead, naval facilities ashore at Port Blair were used for communicating with Naval Head Quarters and the Eastern Naval Command HQ at Vizag. Port Cornwallis lacked any naval organization and when the need arose to contact Vizag for some urgent supplies, I found a police wireless station on the island to transmit our signals from.

Meanwhile, Ghazi kept operating off Vizag in search of Vikrant, believing it to be there thanks to the dummy traffic and radio silence, when, in fact, the carrier had already moved to the Andaman Islands. Ghazi sank off Vizag on the night of 3-4 December, ceasing to be a threat. Vikrant launched air attacks at Cox’s Bazar, Chittagong and other ports immediately on commencement of war, catching Pakistan by complete surprise and our Fleet was exercising total control over the Bay of Bengal.

When planning for the war, Indira Gandhi and the three service chiefs considered the possibility of a third country intervening. China was thought to be a risk as it could potentially come to the aid of Pakistan by creating tension along the Sino-Indian border, thus tying up large numbers of our forces. Winter was chosen for the operations so that snow would prevent any meddling by the Chinese.

As it happened, it was the US that threatened intervention. On 10 December, it announced with much fanfare that the Seventh Fleet, normally operating in the Pacific Ocean, would enter the Bay of Bengal. Gandhi summoned Admiral Nanda, who told her that if the US Navy interfered with our ships, it would be an act of war. He wondered if the US would really want that but believed that the US was only trying to bully us, and that we should fearlessly continue with our operations. He also said that he was going to tell his ships that if they come across American ships, they should exchange identities and invite their Captains for a drink! Gandhi was quite satisfied with the Admiral’s answer.

At sea, we learnt that a US Task Force led by their biggest aircraft carrier, the nuclear-powered Enterprise, had been directed to sail into the Bay of Bengal. US National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger, wanted this widely publicized with the ships sailing through the Malacca Straits in broad daylight. The Commanding Officer of one of our Fleet ships, Beas, sent a signal by light to the Fleet Commander, Admiral Sarma, asking what our ships were to do should they encounter the Seventh Fleet. The Admiral’s reply was short and crisp: “Exchange identities and wish them the time of day”. Morale on Vikrant was high and everyone’s attitude was, ‘Let’s carry on with our job and tackle any situation as it develops’. As it happened, we never encountered any US ship and saw the war through to the birth of Bangladesh.

Admiral Nanda and Admiral Elmo R Zumwalt, who was then head of the US Navy as Chief of Naval Operations, have described these events in detail in their respective autobiographies. Admiral Zumwalt wrote that despite diplomatic pressure by the US on Gandhi, nothing deterred her from going to war. Henry Kissinger was enraged and ordered Enterprise and other ships to be deployed in the Bay of Bengal. When Admiral Zumwalt asked Kissinger what his ships were supposed to do if they came across the Indian ships, Kissinger replied: “That is your problem”. Admiral Zumwalt wisely told his ships to stay away from East Pakistan and to operate south of Sri Lanka. No wonder we never even saw them on our radar screens.

Years later, after both Chiefs had retired, Admiral Zumwalt came to India and met Admiral Nanda. The former stated that he was worried that should the ships of the two Navies meet during the war, it might lead to an inadvertent situation. When Admiral Nanda told him that his instructions to Indian ships were to invite the US Captains for a drink, Admiral Zumwalt responded, “We need not have worried!”

It seems the ordered entry of US ships into the Bay of Bengal caused more anxiety to their naval personnel than it did to ours. Tailpiece: The meeting between Gandhi and Admiral Nanda on entry of the US ships took place when the Eastern Fleet was at sea. Any instructions from Admiral Nanda to Admiral Sarma could only be through a radio signal which would have been seen by me. I do not recall any such signal and Admiral Sarma’s reply to CO Beas seemed to be totally on the spur of the moment. I have often wondered at the similarity of the language of both the Admirals- was it just pure telepathy?

Ravi Sharma is a retired naval officer who now lives in New Delhi and enjoys blogging his memoirs.

Wreckage of PNS Ghazi found off Vizag in 2024

February 23, 2024: The Times of India

Visakhapatnam: A newly acquired Indian Navy deep submergence rescue vehicle (DSRV) has recently located the wreckage of PNS Ghazi, the Pakistani submarine that sunk on Dec 4, 1971 during the India-Pakistan war, reports Nalla Babu.

The Tench-class submarine, which served earlier in the US Navy as USS Diablo, was found at a depth of around 100 metres about 2 to 2.5 km off the coast. However, Indian Navy does not want to touch it out of respect for those who fell in action, in true Navy tradition, sources here said.

The sinking of PNS Ghazi with 93 men (11 officers and 82 sailors) on board off the coast of Visakhapatnam was considered a high point in the war, which ended with the creation of Bangladesh in 1972.Pakistan had despatched US-made PNS Ghazi to mine India’s eastern seaboard and to locate, shadow and sink INS Vikrant, India’s British-built Majestic-class aircraft carrier.

Operation Trident

K R A Narasiah, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: K R A Narasiah, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

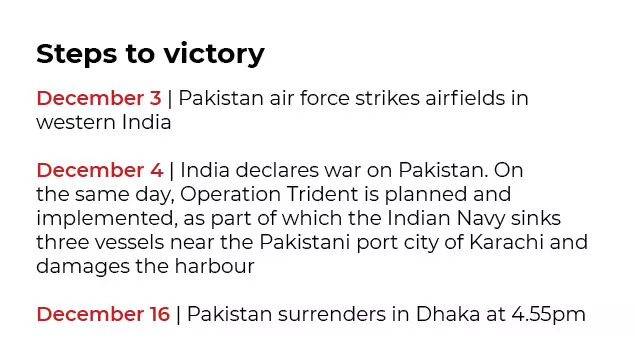

About 50 years ago, on December 4, 1971, during the India-Pakistan war, when the Indian Air Force and Indian Army were mounting an offensive on the ground and in the air, a master plan was devised and carried out by the Indian Navy that became its first full-scale engagement after Independence. The victory on December 4 is celebrated as Navy Day.

The Indian Navy engaged in action against the Pakistan navy on the western front, the year in which hostilities started on the eastern front due to the Bangladesh Liberation War. Named Operation Trident, the plan of the Indian Navy was to block the Pakistani ports. India ended up inflicting heavy damage on Pakistani ships and the harbour of Karachi.

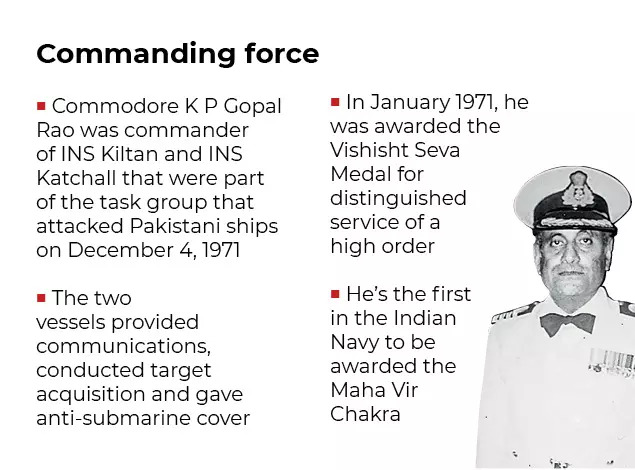

At the heart of this mission was Commodore K P Gopal Rao from Tamil Nadu. He was heading the Arnala class anti-submarine corvettes INS Kiltan and INS Katchall. Deputed at the eastern naval coast at the time, he was called to join the western fleet to head the task group that launched the attack on the Karachi port by the chief of naval staff Admiral S M Nanda.

The group comprised three Vidyut class missile boats, INS Nipat, INS Nirghat and INS Veer, and a fleet oiler INS Poshak. On the intervening night of December 4-5, 1971, during the India-Pak operations, the task group carried out an offensive sweep notwithstanding the threat of air, surface and submarine attack from the other side.

Commodore Rao led his group deep into Pakistan waters and located their warships. Despite heavy gun fire from Pakistan destroyers, he carried out a determined attack which led to the sinking of two destroyers and a minesweeper along with a support supply vessel.

After the surface engagement, Commodore Rao led his team to venture farther and bombarded Karachi port setting fire to oil and other installations at the harbour. The Karachi port sustained severe damages and was left paralysed.

A humble man, Commodore Rao exuded a quiet confidence that motivated all those around him, says his daughter Tara. “At the time of the attack, the sailors were all scared. Realising the sense of unease, my father gave a short talk asking everyone to put aside their fears and focus on duty as a team, so that they could enjoy the victory at the end of it all.”

Vice Admiral (retired) G M Hiranandani, in his memoir, ‘Transition to Triumph’ has recorded with surgical precision the events that took place and quotes Commodore Rao, “The rendezvous with Katchall and missile boats Nirghat and Veer was effected off Dwarka on the afternoon of December 4, 1971...Task Group sailed from Dwarka on December 4, to carry out Operation Trident. Kiltan and Katchall were in the vanguard and the three missile boats stationed slightly in the rear.”

At about 6pm, Kiltan detected the first target, a warship on patrol. The second target was detected as a large unidentified ship. “All ships of the task group were ordered to switch on their radars and acquire the targets. After the missile boats confirmed that they had acquired the targets … I ordered them to proceed with the attacks. Both the missile boats hauled out of the formation and proceeded at higher speeds towards their respective targets,” Commodore Rao is quoted as saying.

For his display of gallantry and outstanding leadership in the best traditions of the Indian Navy, Commodore Rao was awarded the first Maha Vir Chakra in the Navy.

His achievements and his tryst with the armed forces began at the age of 13, when in 1939, during World War II, two British warships docked in Madras. “He was intrigued by the warships and the love for the ocean took him on the journey to become a navy man,” says Tara.