A Handbook Of Some Common South Indian Grasses: 2-Introduction

This is an extract from |

Introduction

Grasses occupy wide tracts of land and they are evenly distributed in all parts of the world. They occur in every soil, in all kinds of situations and under all climatic conditions. In certain places grasses form a leading feature of the flora. As grasses do not like shade, they are not usually abundant within the forests either as regards the number of individuals, or of species. But in open places they do very well and sometimes whole tracts become grass-lands. Then a very great portion of the actual vegetation would consist of grasses.

On account of their almost universal distribution and their great economic value grasses are of great importance to man. And yet very few people appreciate the worth of grasses. Although several families of plants supply the wants of man, the grass family exceeds all the others in the amount and the value of its products. The grasses growing in pasture land and the cereals grown all over the world are of more value to man and his domestic animals than all the other plants taken together.

To the popular mind grasses are only herbaceous plants with narrow leaves such as the hariali, ginger grass and the kolakattai grass. But in the grass family or Gramineæ the cereals, sugarcane and bamboos are also included.

Grasses are rather interesting in that they are usually successful in occupying large tracts of land to the exclusion of other plants. If we take into consideration the number of individuals of any species of grass, they will be found to out-number those of any species of any other family. Even as regards the number of species this family ranks fifth, the first four places being occupied respectively by Compositæ, Leguminosæ, Orchideæ and Rubiaceæ.

As grasses form an exceedingly natural family it is very difficult for beginners to readily distinguish them from one another.

The leaves and branches of grasses are very much alike and the flowers are so small that they are liable to be passed by unnoticed. The recognition of even our common grasses is quite a task for a botanist.

To understand the general structure of grasses and to become familiar with them it is necessary to study closely some common grasses. We shall begin our study by selecting as a type one of the species of the genus Panicum.

Panicum javanicum is an annual herb with stems radiating in all directions from a centre. The plant is fixed to the soil by a tuft of[Pg 2] fibrous roots all springing from the bases of the stems. In addition to this crown of fibrous roots, there may be roots at the nodes of some of the prostrate branches. The stems and branches are short at first, and leaves arise on them one after the other in rapid succession. After the appearance of a fair number of leaves the stem elongates gradually and it finally ends in an inflorescence.

The stem consists of nodes and internodes. The internodes are cylindrical and somewhat flattened on the side towards the axillary bud. When young they are completely covered by the leaves and the older ones have only their lower portions covered by the leaf-sheaths. Usually they complete their growth in length very soon, but the lower portion of the internode, just above the node and enclosed by the sheath, retains its power of growth for some time.

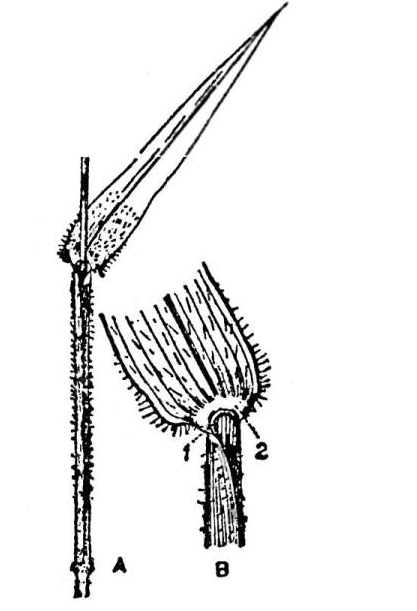

The leaf consists of the two parts, the leaf-sheath and the leaf-blade. At the junction of these two parts there is a very thin[Pg 3] narrow membrane with fine hairs on its free margin. This is called the ligule. (See fig. 2.)

The leaf-sheath is attached at its base to the node and it is slightly swollen just above the place of insertion. It covers the internode, one margin being inside and the other outside. The surface of the sheath is sparsely covered with long hairs springing from small tubercles. The outer margin of the sheath bears fine hairs all along its length. (See fig. 2.)

The leaf-blade is broadly lanceolate, with a tip finely drawn out. Its base is rounded and the margin wavy, especially so towards the base. On the margin towards the base long hairs are seen, and some of these arise from small tubercles. The margin has a hyaline border which is very minutely serrate.

There is a distinct midrib and, on holding the leaf against the light, four or five small veins come in to view. In the spaces between these veins lie many fine veins. All the veins run parallel from the base to the apex. At the base of the blade the veins get into the leaf-sheath and therefore the sheath becomes striated. Just above the ligule and at the base of the leaf-blade there is a colourless narrow zone. This is called the collar.

A. Full leaf; B. a portion of the leaf showing 1. the ligule and 2. the collar.

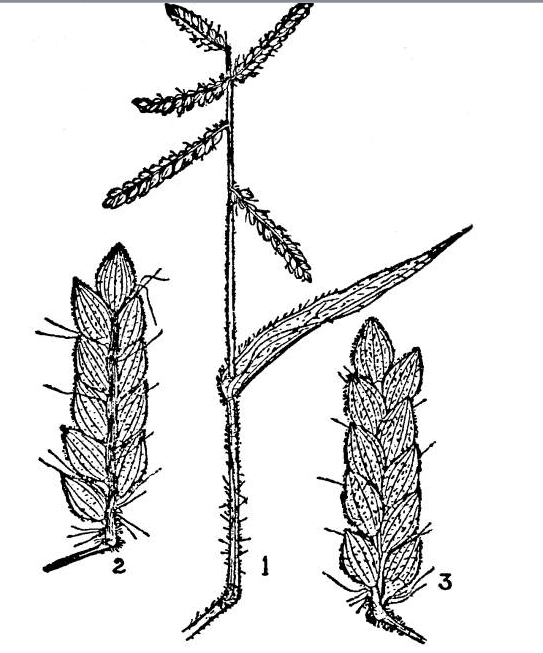

As already stated the inflorescences appear at the free ends of branches. Every branch sooner or later terminates in an inflorescence which is a compound raceme. There are usually five or six racemes in the inflorescence. Each raceme has an axis, called the rachis, which bears unilaterally two rows of bud-like bodies. These bud-like bodies are the units of the inflorescence and they are called spikelets.

1.Inflorescence; 2 and 3. the front and the back view of a raceme.

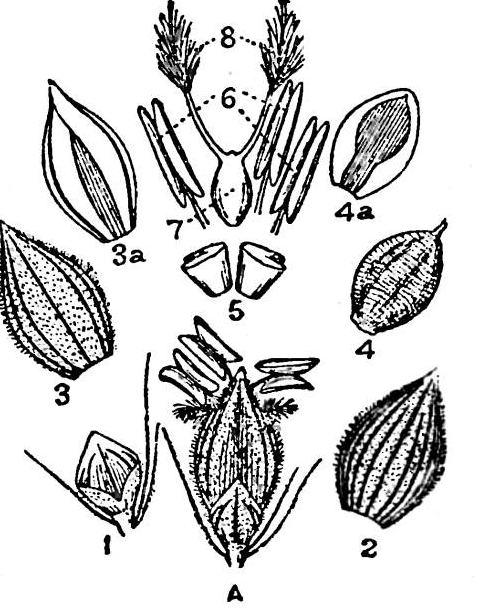

The spikelets are softly hairy and are shortly stalked. The pedicels of spikelets are hairy and sometimes one or two long hairs are also found on them. Each of these spikelets consists of four green membranous structures called glumes. The first two glumes are unequal, the first being very small.

The second and the third glumes are broadly ovate-oblong with acute tips. Both are of the same height and texture, but the second is 7-nerved and the third 5-nerved. The fourth glume is membranous when young, but later on it becomes thick, coriaceous and rugose at the surface. Just opposite to the fourth glume there is a flat structure with two nerves, similar to the glume in texture.

This is called the palea. The fourth glume and its palea adhere together by their margins. Inside the fourth glume and between it and the palea there are three stamens and an ovary with two styles ending in feathery stigmas. Just in front of the ovary and outside the stamens two very small scale-like bodies are found.

These are the lodicules. They are fleshy and well developed in flowers that are about to open. In the spikelet there is only one full flower. The third glume contains no flower in it, but occasionally there may be in its axil three stamens. The first two glumes are always empty and so they are called empty glumes. (See fig. 4.) In mature spikelets the grain which is free is enclosed by the fourth glume and its palea.

A. A spikelet; 1, 2, 3 and 4. the first, second, third and the fourth glume, respectively; 3a. palea of the third glume; 4a. palea of the fourth glume; 5. lodicules; 6. stamens; 7. ovary; 8. stigmas.

On account of the scarcity of fodder, people interested in agriculture and cattle rearing have very often imported[Pg iv] foreign grasses and fodder plants into this country, but so far no one has succeeded in establishing any one of them on any large scale. Usually a great amount of labour and much money is spent in these attempts.

If the same amount of attention is bestowed on indigenous grasses, better results can be obtained with less labour and money. There are many indigenous grasses that will yield plenty of stuff, if they are given a chance to grow. The present deterioration of grasses is mainly due to overgrazing and trampling by men and cattle.

To prove the beneficial effects which result from preventing overgrazing and trampling, Mr. G. R. Hilson, Deputy Director of Agriculture (now Cotton Expert), selected some portion of the waste land in the neighbourhood of the Farm at Hagari and closed it for men and cattle. As a result of this measure, in two years, a number of grasses and other plants were found growing on the enclosed area very well, and all of them seeded well. Of course the unenclosed areas were bare as usual.

In the preparation of this book I received considerable help from M.R.Ry. C. Tadulinga Mudaliyar Avargal, F.L.S., Assistant Lecturing and Systematic Botanist, in the description of species and I am indebted to M.R.Ry. P.S. Jivanna Rao, M.A., Teaching Assistant, for assistance in proofreading.

I have to express my deep obligation to Mr. G. A. D. Stuart, I.C.S., Director of Agriculture, for encouragement to undertake this work and to the Madras Government for ordering its publication.

For the excellence in the get up of the book I am indebted to Mr. F. L. Gilbert, Superintendent, Government Press.

K. RANGACHARI.

Agricultural College,

Lawley Road, Coimbatore,

2nd June 1921.