Abu’l Hasan, Mughal artist

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Hasan’s life and work

B.N. Goswamy |A truly rare talent Sunday, August 18, 2013 | The Sunday Tribune

Abu’l Hasan, a painter in the court of Jahangir, was an artist gifted with deep psychological insight, observation and workmanship

On this day, Abu’l Hasan, the painter, who has been honoured with the title Nadir-al Zaman, drew the picture of my accession as the frontispiece to the Jahangir Nama, and brought it to me. As it was worthy of all praise, he received endless favours. His work was perfect, and his picture is one of the chefs d'oeuvre of the age. In this era he has no equal or peer.

Emperor Jahangir in Tuzuk e Jahangiri

The title that the Emperor conferred upon the painter can be differently translated of course - ‘Rarity of the Times’, ‘Wonder of the Age’, ‘Zenith of our Times’ — but whichever way one translates, it sits perfectly. For Abu’l Hasan was a truly rare talent: a child prodigy; someone possessed of singular skills of observation and workmanship; as an artist gifted with deep psychological insight. "His work was perfect", as the Emperor observed.

Son of Aqa Riza, who came to India from Iran about 1560, and took up employment in the great Mughal studio, Abu’l Hasan had shown signs of precociousness very early on. And it is to those precocious skills — rather than to the words that one uses — that one must turn to get a sense of his prodigious powers. Those were the days when European works, especially engravings, had started making their way to Mughal India, brought in by Jesuit priests and diplomatic personages.

Among those seems to have been a 1511 engraving by Durer showing St John standing close to the foot of the crucified figure of Christ. There are other grieving figures in the engraving, but somehow Abu’l Hasan seems to have picked only the figure of St John to copy. And this, he did in the form of a stunning brush drawing on paper which is now in a museum at Oxford.

There, in this very lightly drawn study, he stands — St. John — body mildly flexed, hands clasped in front at waist level, head somewhat tilted and an expression of ineffable sadness on the face. Nothing that is there in the figure Abu’l Hasan could have observed from life or been familiar with personally: the European features of the face, the curly hair, the costume with its palpable weight and folds. Nor could he have had any instruction in European technique: modelling, shading, sense of volume, and all. And yet, basing himself simply on the engraving which must have come his way, he turned out this remarkably sensitive study.

What adds enormously to one’s admiration is what the barely visible — so rubbed it is — inscription in Persian at the bottom of the page, which reads: "mashq-i Abu’l Hasan ibn-i Riza, murid-i Shah Salim, dar sinn-i sizadah salagi sakhta"; meaning, of course, "an exercise (in drawing) by Abu’l Hasan, son of Riza, devoted follower of Shah Salim (i.e. Jahangir), done at the age of 13 years."

Two years later, when he must have been 15, Abu’l Hasan turned out another astonishing painting, also based evidently upon a European work. It shows Neptune, Lord of the Seas, in a style that was entirely alien to the painter’s own tradition. There is wild grandeur in the naked, muscular, trident-bearing figure of the Roman god, astride a mythical, horse-bodied, fish-tailed, lobster-legged mount, wading through the rough seas astir with creatures gazing at the sea-lord with fear and astonishment.

Nothing seems to have escaped Abu’l Hasan’s eye in this, from the angry mane alike of the rider and horse to the tiny swooping pelican close to the god's head.

For an Indian painting, descended as it was from the artistic ancestry of Persian and Mughal painting, the work was something of a tour d’ force, as much on account of the painting as of the four lines of inscription in Latin at the bottom which Abu’l Hasan seems to have copied exactly, elegant stroke by stroke, loop by loop, without knowing a word of the language or the script. And the inscription in Persian at the bottom? Once again, that this is the work — an 'aml, not a mashq — of Abu’l Hasan son of Riza, devout adherent of Shah Salim.

But copying European works was not the only, or even the preferred, groove in which Abu’l Hasan’s talent moved: he had obvious gifts in the area, but there was more, much more, that he painted that was in consonance with his training and his wont.

The superbly finished frontispiece to the Jahangir Nama to which there is reference by the Emperor above; the moving portrait of a fragile old pilgrim standing, perilously close to the end of his life; the scene of the emperor Jahangir giving audience —jharokha darshan — from a window of the palace placed high above everyone and everything else; the study of squirrels in a plane tree; ‘portait’ of a spotted forktail bird; the Emperor Shah Jahan examining the Imperial seal: the list is long and the work truly breathtaking. But there is also a glittering painting of an imaginary meeting between two great emperors: Jahangir of India embracing Shah Abbas of Persia.

The painting is replete with symbols and is obviously allegorical: the sun and the moon forming a halo against which the heads of the twosome are limned; the winged cherubs who keep the halo aloft; the lion and the lamb under the feet of the two emperors; the globe marked by a map of the world on which they stand.

A host of poetic compositions appear on the page: celebrating the imagined ‘event’, invoking the blessing of the Almighty upon the emperors, notes on what is observed and what is conceptual, and so on. But also a brief note in the neatest of hands: "The work of the devoted servant, Nadir-al Zaman, son of Aqa Riza".

An afterword: There is a small but deeply moving portrait of Abu’l Hasan as a young man, which has survived on the borders of a page of the famous Gulshan Album of paintings, now in Iran.

There he sits, this man of undoubted genius, utterly absorbed in his work: seated on the floor, one knee raised and supporting a wooden tablet with a sheet placed on it on which the painter is drawing, slim brush in the left hand with which he draws, the right pressing the sheet down; head bent, eyes alight, a look of complete concentration on the face.

There are the instruments of his trade lying on the ground next to him. But clearly the man appears as if he has shut the world out of his system. Nothing else than his work exists for him. At least at this moment.

Copying Durer, other Europeans

Salman Toor | Wonder of the Age |20 Dec 2013 | The Friday Times

What happened when the Mughal-era miniaturist Abul Hasan sat down to copy the European painter Albrecht Durer? By Salman Toor

Albrecht Durer was the Da Vinci of the Northern Renaissance, the artist who first fused the traditions of Northern art with the discoveries of the Italian Renaissance.

Consider his Crucifixion with the Virgin Mary and St. John (figure 1). It has all the macabre qualities and gothic gravitas associated with the Northern Renaissance.

Now imagine Durer’s surprise if he were to find that this engraving was being passed around young picture-makers in a royal atelier in Mughal Emperor Jehangir’s India, only a decade or two after Durer’s death. Imagine Abul Hasan, the child prodigy, turbaned and barefooted, sitting with his legs crossed and hunched over a flat wooden board in that quiet but busy quarter. All around him are scraps of napkins and bottles of powdered pigments, messy mixing bowls and needle-thin brushes. Picture him squinting his Afghan eyes (his father was a painter from Herat) at Durer’s print, then nimbly setting his mark on the crisp new paper: his brush quivers but his faith in his gift is unwavering.

I wonder what he’s thinking when he looks at that grave woodcut print. He probably finds it a bit dry, given his exposure to the exuberance of the colorful and bon vivant court of possibly the richest king on earth. Why make dreary pictures to teach piety to ordinary people when a picture can summon the sublime, inspire awe, and bestow saccharine, Persianate praise on the well-born?

The Durer print was probably gifted to Jehangir by the English ambassador Sir Thomas Roe. But just hold Durer’s original print and Abul Hasan’s copy of it side by side and the question of why he was copying it may become unnecessary.

An engraving is made by incising on a wood or metal surface, which is then inked and printed in a press. It is somewhat like an etching, but much less forgiving. Engravings were wildly popular in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries because, unlike paintings, which could be part of inaccessible private collections or sedentary and permanent features of famous chapels, engravings could be produced in great numbers and were portable across the borders of what would soon become Protestant lands and the famous Inquisitorial theater of the Counter-Reformation. Engravings were how, for instance, a German artisan would know about the celebrated new pictures of the Italian Renaissance –engravers would make faithful copies of their compositions. And this is how he could incorporate groundbreaking Renaissance discoveries about anatomy composition and perspective into his own pictures.

Durer has drawn St John and Mary soberly contemplating the crucifixion of Jesus, with Mary Magdalene, another saint, and Jesus’s Roman tormentor lurking in the background. Durer has foreshortened St John’s face as he looks up at the cross so that we can look up his nostrils and the gap-toothed gum under his upper lip. I imagine an angle like this would have seemed rude to a Mughal miniaturist. Durer’s perspective suggests we are viewing the figures from a low angle; they are at a height above us and that literally puts this holy event on an elevated status, one the viewer is not “on par” with. A miniaturist’s solution would be to put the looker (us or himself or a minion) in the picture and draw him as a midget in profile to show the degrees of star-power of various characters within the important event. A tad simple, a tad didactic, similar to early Christian icons, but nonetheless effective as a narrative tool.

This is why Abul Hasan cannot understand foreshortening even when it’s in front of him. This confusion becomes a larger problem of perspective that can be seen again and again in the quaint representations of architecture in relation to the human body in miniature painting. (Abul Hasan is an exception. His perspective, even in miniature painting, is almost perfect; and this has something to do with his extraordinary powers of simulating the lessons learned from his exposure to European art.) He doesn’t understand that what seems wrong in the process of drawing makes a sketch plausible when it is regarded by the eye. For instance, John’s head seems too tilted for a Mughal painter who is used to aquiline profiles. So the Mughal painter lifts it in an effort to tidy it, stiffening it in the process. He airbrushes the unflattering angle of the nostrils. He still makes an effort for the saint to give that very Christian pose of the upward melancholy gaze but because he doesn’t know what happens to a round temple and wet eyes when seen from below, his drawing of St John’s eyes is skewed, resembling someone caught half-blinking in a photograph.

(Abul Hasan’s picture is what most miniature illuminations look like before they were colored. Ironically, most European Old Master under-paintings looked the same under layers of colored glazes! A monochrome raw umber or sienna drawing usually.)

Abul Hasan has drawn the figure with a thin brush. He doesn’t want to move too fast, drawing with a flow his training could afford him. He is treading, after all, on foreign ground. He has to make a smooth drawing, worthy of a king, out of a mad foreign picture. He must be scared.

He traces the major lines in the saint’s clothes. But where the European painter would revel in the beautiful possibility of the folds of creasing fabric, the young Abul Hasan becomes confused and loses interest. Just look at how he apes the eccentricity of Northern drapery on his saint’s sleeve. It’s too much for him! Cluttered and unnecessary. A madness! Why would anyone want to create such a confusion? If there had been embroidery and brocade here, or jewels of some sort, he would have drawn them with a feverish passion. But this is just cloth. And it’s not even silk!

He clearly loves the curls on John’s head and has made a poignant effort to be faithful to them. He has even used the brush like the incising tool used by an engraver, totally linear. No fine airbrushing here! You can see every little line used to describe the flow of hair in Durer’s print, but Abul Hasan’s curls are tedious details that get carried away and forget the shape of the head on which they happen to sit. Durer anticipates a scalp under the strands of hair, stretched over a skull and a more or less plausible body underneath John’s clothing. But in the miniaturist’s training, his way of looking, the fabric becomes an end unto itself. It has a somewhat distant relation with the body it could conceal (unless the miniaturist wants to show sheer fabric for the purposes of preciousness or pornography). It is an idea of a fabric, and that is quite enough to give pleasure to the eye and provide meaning to the story being told. Mughal painters certainly focus on details of costume (they share that love of costume with the European tradition) but without a deep curiosity about the textures of different materials, or the nature of a costume subject to wind and weather. But no matter! The lucky painters of the royal atelier are trained to summon the divine, the sublime, through elements other than the human body. They do this usually through ornamentation, touching the very limits of delicacy. The body with its expressive contortions and its capacity for pain was not exactly useless in the miniature tradition, because there are famous examples in Abul Hasan’s work which prove otherwise. But the body in Mughal India was not, as it was in the European tradition, a heroic yardstick with which to measure the pains and pleasures of the world.

For us, today, Abul Hasan’s drawing is wonderful because of its innocence: the artist doesn’t know he is participating in the first improbable meeting of aesthetics from worlds far apart.

That Abul Hasan chose Albrecht Durer, a master of the Northern Renaissance, is peculiar. The Northern artists were different in their tempered Christian earnestness from those sunny, passionate Italian inheritors of the Roman love affair with the human body. The Northern Renaissance was drearier, excelling not in the depiction of bodily ecstasies and expensive garbs, but in pain, dark comedy, peasantry, landscape, torture, a kind of edited realism that the Italians would have found vulgar. (Just look at the nail hammered viciously through the bones of the foot of Jesus in the engraving by Durer. Also look at the macabre Grunwald altarpiece and you’ll see what I mean.) I imagine an Italian painting from the late 16th century would have been way more impressive to a painter working in the royal atelier in India than a print of Durer’s.

But Abul Hasan probably had no choice in the matter. He was ordered to paint this image. He was a well-known art star and he could produce the best likenesses, so Jehangir summoned him to win a wager with Sir Thomas Roe. Roe had brought “pictures” from an unidentified European master for Jehangir who:

took extreme content, showing it to everie man neare him; at last he sent for his cheefe paynter, demanding his opinion. The foole answered he could makes as good wherat the King turned to me, saying my man sayth he can do the like and as well as this: what say yow? I replyed: I knew the contrarie…for I know none in Europe but the same master can performe it…

At night he sent for mee, being haiste to triumph in his workman, and shewed me six pictures, five made by his man, all pasted on one table, so like that I was by candle light troubled to discern which was which…

This ‘cheefe paynter’ was probably Abul’ Hasan, and he was only twelve years old at the time.

Sadly, only some biographical details about him are available to us. Chiefly: he was the son of Aqa Reza, a man in the employ of Jehangir, who gave him the title Nadir-uz-Zaman, Wonder of the Age. Funnily enough, he would use this title to sign his pictures. Imagine him thinking: If you’re consequential, you’ll know who I am. In those days in India, the Emperor seems to have given a title to almost everyone around him (could you please ask Wonder of the Age to polish those five sketches by tomorrow morning? The King of Kings [Jehangir] and Paragon of the Palace [Noor Jehan] are losing patience…)

Other celebrated works

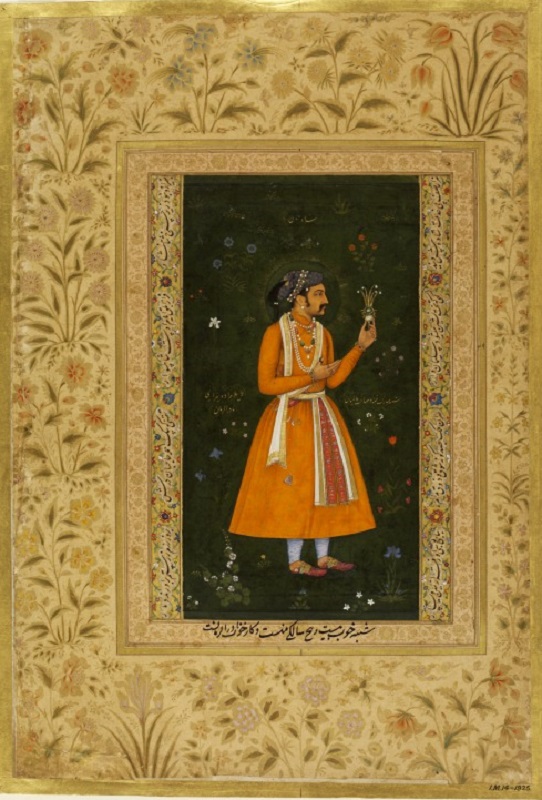

Portrait of Shah Jahan as a young prince

In later years, Shah Jahan added the Persian inscription in black ink in the border, noting that it is 'a good likeness of me in my twenty-fifth year and it is the fine work of Abu'l Hasan'.

The minute Nasta'aliq inscription in gold beginning on the right of the green ground, under Shah Jahan's hand, and continuing on the left beneath his right elbow may be translated: Blessed likeness of the qibla [the direction of Mecca] and master of mankind / the work of the [artist] born in hereditary palatial service Nadir al-Zaman. The title 'Shah Jahan' is written above his head in gold. Victoria & Albert Museum

Artist: Abu'l Hasan was the son of the Iranian painter Aqa Reza, in the service of the future Mughal emperor, Jahangir. Abu'l Hasan grew up in the prince's household and became so valued as a court artist that he was called "Nadiru'l Zaman" - Wonder of the Age.

This reflects painting's high status at Jahangir's court. Jahangir wrote: "My liking for painting and my practice in judging it have arrived at such a point that when any work is brought before me, either of deceased artists or those of the present day, without the names being told me, I say on the spur of the moment that it is the work of such and such a man."

Painting had become an important aspect of Mughal culture during the previous reign of Akbar; his tenure's official history, the Akbarnama , contained vivid, dynamic pictures. But it was Jahangir who really loved this art. He had paintings made of rare birds from Goa and spring flowers in Kashmir. When James I's ambassador, Thomas Roe, visited the court in 1616 he disparaged Jahangir's painters in comparison to the miniature he had with him by the English artist Isaac Oliver. Within three weeks Jahangir showed him copies by his artists, challenging him to identify the original. Roe admitted it was very difficult.

Subject: Shah Jahan (reigned 1628-56) later wrote on the border of this portrait: "A good likeness of me in my 25th year and the fine work of Nadiru'l Zaman." He was Jahangir's third son.

The Mughals conquered the Delhi sultanate in 1526, ruled northern India by 1600 and controlled most of the subcontinent by 1700. In 1631 Shah Jahan's wife, Mumtaz Mahal, died while giving birth to her 14th child. He built one of the world's great structures as her mausoleum - the Taj Mahal. He also built a fabulous palace inside the Red Fort at Delhi, with a heavenly atmosphere summed up in an inscription: "If there be Paradise on the face of the earth, it is this, it is this."

In 1657 Shah Jahan became ill. Each of his sons declared himself emperor. One, Aurangzeb, prevailed. Shah Jahan lived on, imprisoned in the fort at Agra, until 1666. From there he could at least see the Taj Mahal. When he died he was buried there, next to Mumtaz Mahal.

Distinguishing features: In bold orange, against a field of flower-studded green, Shah Jahan holds up, in fine connoisseurship, a gold spray containing a massive green emerald and a white diamond. More jewels cover him: a necklace with big pearls, rubies, emeralds, bracelets, pearl earring, turban band, rings. These riches are set within the closely observed beauty of nature. Flowers fill the painting in gouache and gold: among the blossoms the prince himself is a young bloom, a promise of springtime, renewal.

Seen in profile, with meticulously coiffed sideburn and moustache, the prince gestures in appreciation at the amazing artefact he holds up. Around his head is a dark halo, around the picture an elaborate border with floral patterns and inscriptions. This exquisite, graceful painting witnesses not just the wealth of the Mughal court, but the value placed on sensitivity and taste. The young prince is shown appreciating fine things, in harmony with nature.

Inspirations and influences: The Italian Renaissance painter Raphael influenced the art of the Mughal court. In about 1598 Jahangir directed one of his artists to copy a Flemish print of Raphael's Deposition from the Cross .

Where is it? Victoria and Albert Museum, London SW7

Spotted Forktail, folio from the Shah Jahan album

Artist: Painting by Abu'l Hasan (born ca. 1588/89, active 1600–1628)

Calligrapher:Mir 'Ali Haravi (d. ca. 1550)

Date:recto: ca. 1610–15; verso ca. 1540

Medium:Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on silk

Dimensions:H. 15 3/16 in. (38.6 cm) W. 10 3/8 in. (26.3 cm)

Jahangir (r. 1605–27) ordered this portrait of a spotted forktail from Abu'l Hasan, the artist upon whom he bestowed the honorific title "Wonder of the Age." The inscription states that the emperor’s servants hunted this particular bird but does not say whether they killed it or merely captured it before it was portrayed. The silk ground adds a particular luster to the painting, further enhanced by the bird’s shiny eye, which contains glittering chips of a reflective material, probably mica.