Africans in Indian history

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

I

WHEN BLACK WAS NO BAR

Manimugdha Sharma The Times of India Oct 10 2014

Arab traders brought them as slaves but once in India, Africans did not face racial discrimination. They could rise in military service or the courts of emperors, and some went on to found dynasties.

Behind the high walls of a lost fortress in what is today south Delhi blossomed the love story of Delhi's first woman ruler and her Abyssinian general.Historians are divided if it was love or just a strong bonding, but popular literature has forever paired Razia Sultan with Jamal-ud-din Yaqut. Yet it was this love or bonding that doomed both. The powerful Turkic nobles in Razia's court loathed the meteoric rise of Yakut from a slave to Amir ul Umara (premier noble). We don't know if he was hated for the colour of his skin, but the Turks pejoratively referred to him as “habshi“ (someone from Al Habsh or Abyssinia, the modern-day Ethiopia) and considered him inferior to them.

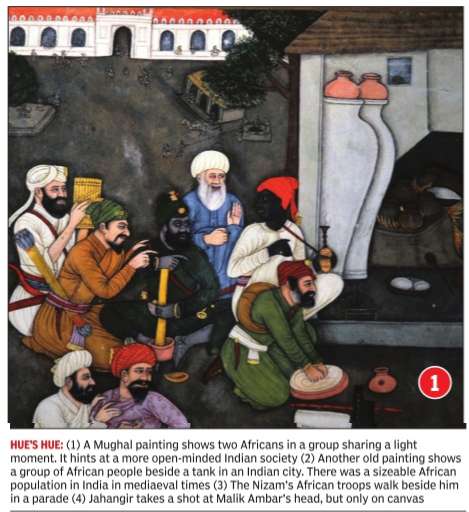

There is a Mughal paint ing depicting two Africans in a group sharing a light moment. It hints at a more open-minded Indian society in the mediaeval period. “It amazes us to this day how Indian society was so remarkably open in the past. It didn't distinguish between whites and blacks. The idea behind our exhibition was to showcase this multicoloured picture of India and the contribu tion Africans made towards completing it. We chose the title because the Indian masses today do not know much about the Afro-Indian community . Through these stories people will know that Africans did not come to India yesterday and will get an insight into the rich history of the AfroIndians,“ said Dr Sylviane A Diouf, curator. The journey of Africans to India was itself fascinating: captured by Arab slave traders, they were packed into hell ships that came to India via the Indian Ocean and its surrounding seas. They were bought by kings, princes, rich merchants and aristocrats and were referred to as habshis or Siddis. But not all remained slaves. Some like Yakut made their own destiny .

Malik Kafur, for instance, was a transgender slave bought by Sultan Alauddin Khilji's general Nusrat Khan for a thousand dinars. Kafur caught the fancy of the sultan and rose through the ranks, becoming his deputy and entering history books as Nawab Hazar Dinari. In his last days, an enfeebled Khilji was at the mercy of Kafur who effectively ruled Delhi and also played kingmaker after the sultan's death.

In the Deccan, Africans made a deeper impact on the political landscape. One of the architects of the Deccan's resistance to Mughal expansion was Malik Ambar, an African who served as prime minister and general of Ahmadnagar, one of the offshoots of the Bahmani kingdom.

Ambar is said to be the father of guerrilla warfare in India since he used his Maratha cavalry to harass the Mughals with great effect. Frustrated, Emperor Jahangir nursed extreme hatred for Ambar, and one of the paintings at the exhibition shows him firing arrows at the severed head of Ambar--a fancy he could only realize on canvas.

The Bijapur state had a clique of habshi nobles led by Ikhlas Khan, a powerful general. That the title `Khan' (reserved only for people of high birth at that time) was bestowed upon him shows that Africans could break the glass ceiling.

Some Africans, like the Siddis of Janjira, even set up independent kingdoms. The Siddis commanded Mughal navies and were respected by both Marathas and the European powers. The Janjira state and its successor state of Sachin survived until Independence.

An exhibition called `Africans in India: A Rediscovery' has been put together by Schomburg Center of New York Public Library. It traces the extraordinary achievements of Africans in India since the 1300s.

“India has been a long-time meritocracy. Whatever your background, you could move up the ranks. Nowhere else in the world have Africans been able to rule outside Africa,“ said Dr Kenneth X Robins, curator.

II

In the latter half of the third decade of the 13th century , there was a scandalous rumour in Delhi: one that linked India's first Muslim woman ruler, Sultan Raziya, with her Abyssinian general Jamal-ud-din Yaqut.

Nobody could say it for sure if the two were romantically involved, but the rumour helped conspiring nobles in the royal court to kill two birds with one shot -delegitimise the rule of a woman sultan by arraigning her character, and portray a very powerful noble as a perfidious man indulging in amoral dalliances with the ruler of the realm.

This powerful Turkic clique, called the `chahalgani', had another reason for disliking Yaqut--he was a `habshi'.

The recent spate of racial attacks on people of African origin in Greater Noida has brought to focus once again the xenophobia that blacks inspire among Indians.

One just has to pore over news reports, or hear things said on the ground for the last couple of days, to find multiple instances of the use of `habshi' by those treating black Africans with suspicion. Though it's doubtful how many people actually know the historicity of the term or its association with Delhi.

Back in the medieval age, the Horn of Africa was the favourite hunting ground of slave traders, first the Arabs, and then Europeans. A region of the Horn of Africa was referred to as Al-Habash by the Arabs and its people, the Habashis or Abyssinians.

When these people came to India, either as traders or slaves, they were referred to as `habshis', a Persianised version of habashis. And just as it happens with time, the term came to be associated with any black person in India. But while it's unknown what sort of experience African merchants and traders had in India, many of those who came as slaves were destined for greatness.

The Mamluks, who were the first Muslim dynasty to rule from Delhi, were slaves themselves but not in the modern understanding of the word. The egalitarian nature of medieval Islam meant that being a slave didn't lock the fortunes of a man -a slave could rise to nobility and even kingship if he had it in him. And since these sultans promoted meritocracy, it ates promoted meritocracy , it was perfectly possible for a black African slave to rise through the ranks and even become king. And no, they didn't need the help of fairness creams to gain acceptability in Indian society.

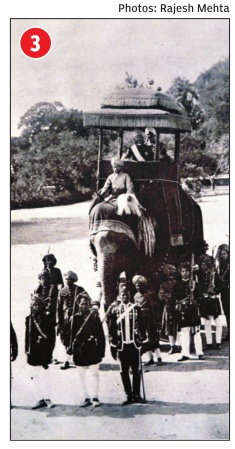

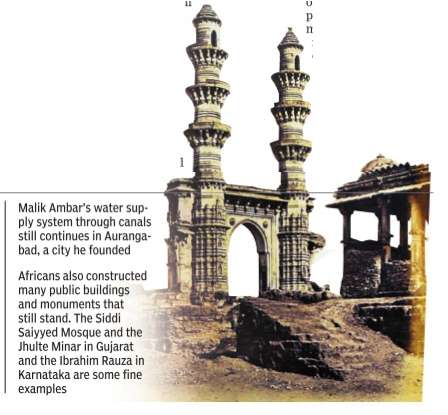

The Deccan, in particular, became a land of opportunity for African slaves, who influenced the political landscape. The most famous among them was Malik Ambar, the prime minister of Ahmednagar and Bijapur, the splinter states of the Bahmani Sultanate. It was he who had led the long resistance against Mughal expansion. It was he who frustrated Akbar and his son Jahangir. And it was he who had famously roped in the Marathas in this struggle and taught them the shoot and scoot tactics (ganimi kava) for which they became renowned. Bijapur, in particular, had many high-ranking nobles of African extraction led by another legendary general, Ikhlas Khan (the fact that he got the title Khan is a statement of the open-mindedness of the Indian society of the time). Also in the Deccan rose a full-fledged dynasty of African rulers in the Siddis of Janjira. Originally allies of the Bijapur Sultanate, the Siddis later became Mughal allies. After losing naval power to the British, they managed to retain their state and found another independent state called Sachin in Gujarat. Both continued until India's Independence.

Elsewhere in the east, four African slaves-turnedsultans ruled Bengal in quick succession, between 1487 and 1494. That period is referred to as `Habshi Rule'.

However, it would be wrong to assume that all was hunky dory even when these fascinating and highly talented men held sway . Political opposition to them would often be coloured with racial hatred. For instance, Jahangir got a dream sequence captured in canvas where he shot an arrow on the severed head of Malik Ambar while abusing him for his colour and African descent. In reality, Jahangir could never defeat Ambar. Cut to modern times and there is little or no memory left among Indians of the African association they once had. What has survived, unfortunately , is the racial hatred, now only more pronounced, as the Greater Noida episode has shown.

Rulers

Adrija Roychowdhury, May 27, 2016: The Indian Express

From: Adrija Roychowdhury, May 27, 2016: The Indian Express

From: Adrija Roychowdhury, May 27, 2016: The Indian Express

From: Adrija Roychowdhury, May 27, 2016: The Indian Express

From: Adrija Roychowdhury, May 27, 2016: The Indian Express

From: Adrija Roychowdhury, May 27, 2016: The Indian Express

From: Adrija Roychowdhury, May 27, 2016: The Indian Express

The elite status of the African slaves in India ensured that a number of them had access to political authority and secrets which they could make use of to become rulers in their own right, reigning over parts of India.

“When your family has been ruling for hundreds of years, people still call you by the title of Nawab,” says Nawab Reza Khan, tenth Nawab of Sachin as he traces his family’s regal history. Reza Khan currently works as a lawyer and lives in the city of Sachin in Gujarat. He says his ancestors came from Abyssinia (present day Ethiopia in East Africa) as part of the forces of Babur. Eventually, they conquered the fort at Janjira and later occupied Sachin and ruled over their own kingdoms.

The Nawab of Sachin is a personified remnant of a glorious African past in India. Africans have, for centuries been a part of Indian society. While the slave trade from Africa to America and Europe is well documented, the eastward movement of African slaves to India has been left unexplored.

The systematic transportation of African slaves to India started with the Arabs and Ottomans and later by the Portuguese and the Dutch in the sixteenth -seventeenth centuries. Concrete evidence of African slavery is available from the twelfth-thrirteenth centuries, when a significant portion of the Indian subcontinent was being ruled by Muslims.

There is, however, a major difference between African slavery in America and Europe and that in India. There was far greater social mobility for Africans in India. In India, they rose along the social ladder to become nobles, rulers or merchants in their own capacities. “In Europe and America, Africans were brought in as slaves for plantation and industry labour. In India on the other hand, African slaves were brought in to serve as military power,” says Dr Suresh Kumar, Professor of African studies in Delhi University.

These were elite military slaves, who served purely political tasks for their owners. They were expensive slaves, valued for their physical strength. The elite status of the African slaves in India ensured that a number of them had access to political authority and secrets which they could make use of to become rulers in their own right, reigning over parts of India. They came to be known by the name of Siddis or Habshis (Ethiopians or Abyssinians). The term ‘Siddi’ is derived from North Africa, where it was used as a term of respect.

The Nawab of Sachin and Janjira

The political power acquired by Africans in the Deccan, in particular in Janjira and Sachin, is best demonstrated in a painting by Abul Hasan, that depicts Emperor Jahangir taking aim at the head of the African slave Malik Ambar. The political career of Malik Ambar can be traced back to a time when he was known as ‘Chapu’. He was initially bought as a slave in Ethiopia by an Arab merchant. Later, after being resold a number of times, he somehow landed in the court of Ahmadnagar as one among the hundreds of Habshi military slaves there.

By the mid-sixteenth century, the Mughals had increased their appetite for the South and were aggressively trying to encroach upon the Nizam Shahi dynasty that ruled much of Deccan. In 1600 AD, the Ahmadnagar fort finally fell into the hands of the Mughals. However, the presence of the Mughals in the Deccan was still limited and Ahmadnagar’s surrounding countryside still lay with the troops deployed by the Nizam Shahi state of which Malik Ambar was a part.

It was during this period that the African slave grew to be a political game changer. Commanding a troop of 3000 cavalrymen, he proved to be a major obstacle to the Mughals’ appetite for the Deccan. The painting by Abul Hasan is testimony to what a nuisance the Ethiopian soldier had become to the Mughals.

Malik Ambar constructed a fort at Janzira, located in the Konkan coast, by the end of the sixteenth century. It still stands intact, currently under protection of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). At Janjira, the Africans developed their own kingdom (with their own cavalry, coat of arms and currency) which the Mughals and Marathas failed to occupy despite repeated attacks. Later, the African rulers of Janjira went on to occupy another fort at Sachin in modern day Gujarat. The present Nawab of Sachin, Reza Khan says “the title of Nawab was given to our ancestors by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, since they had not allowed his competitor Shiva ji to occupy the Janjira fort.”

The Habshi Sultans of Bengal

A large number of royal coins found in Bengal tells the story of a time when the region was ruled by Africans who had been originally brought as slaves. Much of Bengal, in the thirteenth century was being ruled by the Muslim Sultans of Delhi. The Bengal Sultanate was established by Shams al-Din Ilyas Shah in 1352. Historian Stan Gordon has recorded that during this period a large number of Abyssinian (inhabitants of Ethiopia in East Africa) slaves had been recruited in the army of the Bengal Sultans. They did not just work in the army, but also rose to get involved in major administrative tasks such as act as court magistrates, collecting tolls and taxes and involved in services of law enforcement.

Eventually, the Abyssinians in the army managed to seize power from the Sultans under the leadership of Barbak Shahzada, and conquered the throne of the Bengal Sultanate. Barbak Shahzada laid the foundation stone of the Habshi dynasty in Bengal in 1487, and became its first ruler under the name of Ghiyath-al-Din Firuz Shah.

Ghiyath-al-Din was followed by three other Abyssinian rulers. His successor, Saif al-Din Firuz is considered the best of the Habshi rulers. “He is said to have been a brave and just king, benevolent to the poor and needy, and a patron of art and architecture,” says Stan Gordon. Firuz is believed to have patronised the building of a number of religious and secular structures. Most well known among these is the Firuz Minar at Gaur which still stands tall, in a good state of preservation. The Firuz Minar is often compared to the Qutub Minar in Delhi, both in appearance and also in its significance of a victory tower.

The Habshi rule of Bengal was very brief and came to an end in 1493 AD, when Sayyid Husain Sharif Makki seized the throne and founded the Husaini dynasty.

Sidi Masood of Adoni

Adoni is situated in Kurnool district of Andhra Pradesh. In the fifteenth century it was part of the Vijayanagar empire. With the decline of the Vijayanagar empire, the city came in the hands of the Bijapur Sultanate. As part of the Bijapur Sultanate, Adoni got one of its most important governors by the name of Siddi Masood Khan. Masood was a wealthy merchant from Abyssinia.

Siddi Masood was the vizier of Bijapur and was virtually the ruler of Adoni. He improved upon the Adoni fort and also built the Shahi Jamia Masjid. Apart from architectural constructions, he is known to have patronised a sizeable number of paintings under his reign. It is possible that he also founded the school of painting at Adoni, which is a variant of the Bijapuri style.

The Abyssinian ruler’s reign at Adoni came to an end when Aurangzeb captured Bijapur in 1686. Records suggest that a dramatic fight took place on the banks of the mosque built by Siddi Masood, following which he surrendered since the mosque was very dear to him. Aurangzeb appointed Ghazi ud-din Khan as governor of Adoni, replacing Siddi Masood.

Apart from the above rulers, historians are still trying to recover more about African elites in the past. It is possible that the first ruler of the Sharqui dynasty in Jaunpur in the fourteenth century was an Abyssinian. African rulership was perhaps also a part of Sind’s history. However, not enough documentary evidence has been unearthed to make these claims.

Presence of Siddis in Contemporary India

Today, approximately 20,000 to 50,000 Siddis are residing in India and Pakistan, with the majority concentrated in Karnataka, Gujarat, Hyderabad, Makaran and Karachi. In contrast to their part of royal privileges, most of them live in conditions of abject poverty.

Anthropologist Kiran Kamal has been working on the Siddi presence in India for the past couple of decades. He lived amongst a group of them in Mundgod Taluk (Karnataka) for a year. “They live in dense forest areas, literally cut off from everyone.” says Kamal. He observed the way Siddis interacted with people in a market place and says that “they would always maintain a distance. There is a strong fear of Non-African Indians. Indians also have a very disrespectful attitude towards them, despite using them for all the hard labour.”

Poverty, lack of access to education and racism are some of the reasons why the Siddis live in solitude today. “They did not even know they originated from Africa,” says Kamal. On being asked about how an awareness of their history might help them, Kiran Kamal says that, “it does help in spurring a motivation from within. But substantially it does not have much value. What is mainly required is that all the Siddis come up socioeconomically and are well integrated into the larger society.”

Dr. Kenneth Robbins, author of “African elites in India”, is of the opinion that it is necessary to shed light on the ruling status of Africans in India. “The purpose is to see India in a different light, to understand social mobility in India. It is important for Indians to take note of the place that Africans had at one point secured in the country.”

“A major difference in the history of African presence in the rest of the world and that in India is that racial discrimination was not a feature. Nowhere else in the world had they ruled. However, I do not know why, this part of their history has been ignored,” says Dr. Suresh Kumar. He goes on to explain that the elite history of Africans in India is particularly significant in today’s times considering that instances of racial prejudices keep occurring in various parts of the country.