Allahabad: socio political history

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Allahabad: socio political history

’From Nehru to Atiq: Don of a new era Home To First PM Is Now Hub For Criminals

Allahabad: The city of Sangam, which was once home to Nehrus and Bachchans, today symbolises the extent to which politics has been criminalised in UP. How else can one explain the phenomenon of a Samajwadi Party toughie with an alleged criminal history, Atiq Ahmed, ascending to power from Phulpur, a constituency that was once represented by former PM Jawaharlal Nehru?

Political observers, however, do not view the rise of an alleged criminal to power with surprise. They claim the constituency emerged as an SP stronghold after successive Congress leaders in the post-Nehru era failed to improve the abysmal conditions of the people there. Today, Atiq is supporting his brother, Mohammed Ashraf’s bid for election from Allahabad City West.

Post-independence, till about 1958, Congress candidates, including Nehru, had won both assembly and Lok Sabha elections from Phulpur. Once a Congress bastion, Phulpur received its first jolt in 1968 byelection when party candidate lost to Samyukt Socialist Party’s Janeshwar Mishra. However, Congress nominee Ram Pujan Patel brought smiles for the party leadership after his triumph in the next election.

Before 1989, there was no caste-based politics in Phulpur. But when the Mandal Commission report was released by former PM VP Singh, the political scenario altered dramatically in this constituency. After 1989, Phulpur voters divided themselves on caste lines and it later emerged as a Muslim stronghold, followed by Yadav and OBCs.

After the caste factor replaced moral values in the area, all political parties have brazenly indulged in caste-based politics, senior Congress leader Mukand Tewari said, adding that the Congress has been making all possible efforts to regain its old glory. In fact, Ram Pujan Patel, who was a Congress nominee, won the 1989 election on Janata Dal ticket. In 1991, Patel again retained the seat on Janata Dal ticket.

After 1993, the area turned into an SP stronghold and its candidates have been winning till date. The party won in 1993, 1996 and 2003 parliamentary elections.

Lok Sabha elections

1951-2019, April 2024

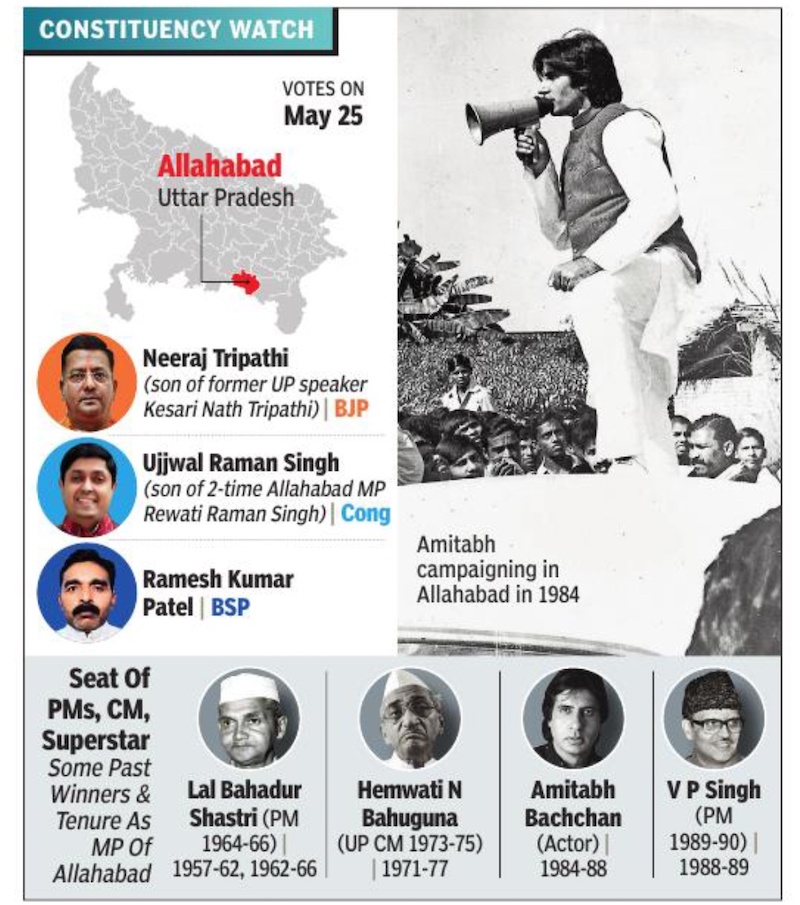

Avijit Ghosh, May 22, 2024: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh, May 22, 2024: The Times of India

Prayagraj (Allahabad) : In the winter of 1984, Allahabad was struck by Amitabh. Paradropped into national politics, the reigning Hindi cinema superstar had returned to his land of birth to challenge the seemingly unbeatable Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna in the Lok Sabha polls. And the erudite city, on the last legs of its old lustre, was swept away.

Vivek Ranjan was only a teenager then, but vividly recollects how feverish young men and women would flock to the special open van, a rarity then, that the actor used for campaigning. “People would line up on roads, wave from balconies,” recalls Ranjan, who runs an NGO. He was also told about an incident when the convoys of the two contestants crossed each other. “Bachchan got down from his van, touched Bahuguna’s feet and asked for his blessings,” he remembers being told.

The election’s outcome surprised many. Adulation had converted into ballots. Bachchan triumphed by 1.87 lakh votes. It was the last time Congress won the seat. Interestingly, BJP’s Ritu Bahuguna Joshi, who won in 2019, is Hemwati’s daughter.

Now, 40 years later, Congress is hoping to retrieve a city that has not only changed political hands and name — it is called Prayagraj now — but also wandered off the map of national relevance.

The city of three rivers was once the garbhagriha of the national movement, a bustling epicentre of knowledge that nourished the likes of Motilal Nehru, Madan Mohan Malaviya, Akbar Allahabadi, Meghnad Saha, Harivansh Rai Bachchan, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Sumitra Nandan Pant, and many others. It was, after all, a verdict in the Allahabad high court against Indira Gandhi in 1975 that changed the direction of India. The city’s centrality, says Sahitya Akademi recipient Neelum Saran Gour, was also tied to the primacy of the Nehru-Gandhi family in Indian politics that’s no longer there. “Even in the time of V P Singh, the city’s politics had a robustness. That season has faded away,” she says.

Allahabad has served as the constituency of Prime Ministers Lal Bahadur Shastri and V P Singh, and prominent politicians like Bahuguna and Murli Manohar Joshi. But the constituency, says social scientist Badri Narayan, didn’t enjoy the kind of infrastructural growth it should have had

“Lucknow, being the centre of state power, and Varanasi, being the PM’s constituency now, have benefited. In comparison, Prayagraj only has Kumbh as a form of sym- bolic power to leverage,” he says.

Much has changed nonetheless. Gour says the city’s infrastructure, orderliness and amenities have improved in recent years. “But one misses Allahabad’s cosmopolitan and open climate when one didn’t have to speak with caution and communities interacted freely and with trust,” she says.

GenNext In Fray

Politics too is in the hands of a new generation. It’s the day of the progeny. Congress candidate Ujjwal Raman Singh, a Bhumihar by caste, is the son of Rewati Raman Singh, a two-time MP from the same constituency, and a Samajwadi Party veteran. Ujjwal served as environment minister when SP governed Uttar Pradesh. The 51-year-old postgraduate in law switched parties last month. SP and Congress have joined hands for the polls.

His BJP rival, Neeraj Tripathi, a Brahmin, is the son of Kesari Nath Tripathi, who, among other things, served as Uttar Pradesh speaker and Bengal governor. Ramesh Kumar Patel, a 47-year-old agriculturist, is BSP’s candidate.

Of the five state assembly segments, a mix of rural and urban, BJP and its allies hold four; SP the fifth. Brahmins, Dalits and Patels (OBC) are numerically weighty, followed by Banias and Muslims. In a city where Ganga and Yamuna converge, the Nishads (boating community), based primarily in villages close to the rivers, are significant. Nishad Party, led by Sanjay Nishad, is in alliance with BJP-led NDA.

The general tone of voters is one of dissatisfaction, irrespective of voting preference. But there’s no overt indication that the social blocs have moved. Geographically, BJP is strong in the urban areas, and SP relatively in villages. “Gaon hamara, shaher tumhara,” jokes an SP supporter, who will vote for Congress. Pintoo Nishad of Arail village owns 10 boats. “Too many boats, too little income,” he says, “The educated among us have nothing to do but take photos of tourists at Sangam.” He is worried whether his two daughters — one studying engineering, the other agricultural science — will find jobs. But when it comes to votes, he says, “Sanjay Nishad jahan bhi honge, hamara vote wohin hoga (We vote for whichever party our leader supports).”

Guru Prasad Prajapati of kumhar (OBC) caste from Kabra village, says, “Women in my household like Modi.” Doodhnath Pathak of Lawayanpur village runs a small eatery. “Poori duniya Modiji ki ijjat karti hai (The world respects Modi). He has done good work, built roads,” he says. But he is personally indebted to Rewati Raman Singh who, he reveals, has helped him on several occasions. “I will vote for his son. But most in my community don’t think like me,” he says.

Corporator Mukund Tiwary, a Congressman, estimates there are about 4 lakh Brahmin voters. “If we get a substantial chunk of them, we have a chance,” he says. Narayan of GB Pant Social Science Institute says the upper-caste votes are going to BJP in the city. “But in rural areas, it will be fractured. The OBC votes too will be divided,” he says.

Past Perfect, Present Tense

Allahabad is defined by divides: past and present, river and class. In 2002, noted Hindi litterateur Gyan Ranjan wrote in the periodical Tadbhav, “Allahabad…cannot go back to what it was, nor can it strike out a new path.”

That may be true, but as Gour says, there is also a sincere attempt to reclaim, virtually and physically, what the city has lost. A Facebook page, Allahabad Civil Lines Nostalgic Memories, started in 2014 and with over 7,000 members, is filled with memories of the city’s mentally exiled. “And there is a profusion of writing about the city. Heritage societies have been set up, literary meets convened, even guava festivals are being organised,” she says.

Reclaiming its politics, and becoming nationally relevant again, though, could be a bridge too far.

Khilona Market

2019: Shastri graffiti from 1962 survives

Rajeev Mani, This wall still seeks votes for Lal Bahadur Shastri, March 31, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rajeev Mani, This wall still seeks votes for Lal Bahadur Shastri, March 31, 2019: The Times of India

A wall in the city carries the legacy of former Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri more than 60 years after he won Lok Sabha elections from Allahabad.

As one enters the busy Khilona Market in Chowk, a porch opposite Kotwali in Loknath area, in red paint across a wall is the slogan: “Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri ji ko vote den, do bailon ki jodi chunav chinnh (Vote for Lal Bahadur Shastri, poll symbol a pair of bulls).” It takes one back to the years of Shastri’s huge influence among Allahabad voters. From 1952 to 1969, Congress poll symbol was a pair of bulls. Shastri won two consecutive terms from Allahabad constituency in 1957 and 1962.

“Before being elected to LS, he was elected to the UP assembly in 1952 from Soraon North and Phulpur West seat,” said Prabhakar Shastri, the former PM’s grandson.

UPCC spokesperson Kishore Varshney said, “During those days, it was enough to write slogans on walls to seek votes for personalities like Shastri. In 1957, he defeated Radhey Shyam Pathak of Praja Socialist Party by a margin of 56,032 votes and later Ram Gopal Sand of BJS by 68,533 votes.”

Shastri was railways minister in the Jawaharlal Nehru’s first Union cabinet.