Animal meat trade: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Illegal animal trade

2010-19

From: Vijay Pinjarkar, February 12, 2020:: The Times of India

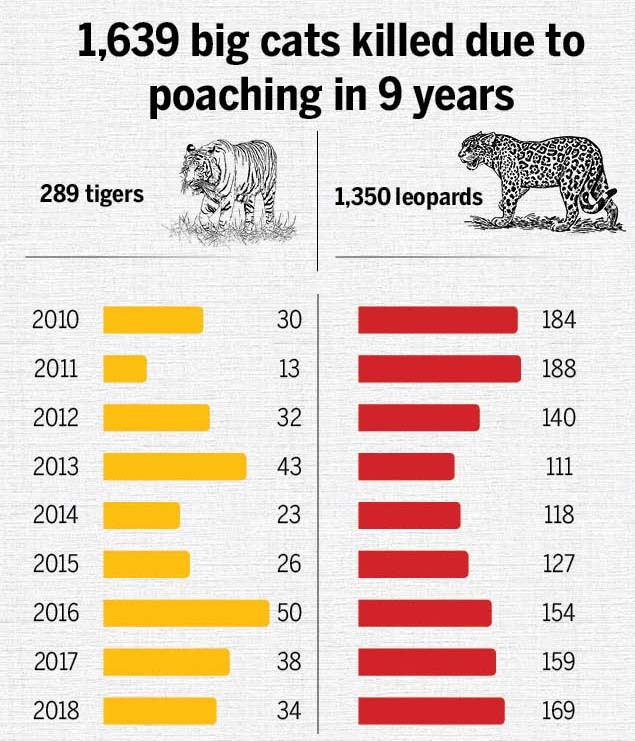

See graphic:

Poaching of cats- tigers and leopards, 2010-19

Chennai: a global hub/ 2019

Siddharth Prabhakar, May 17, 2019: The Times of India

From: Siddharth Prabhakar, May 17, 2019: The Times of India

On February 2, customs officials at Chennai International Airport heard unusual squeaks coming from the luggage of a middleaged man who had just arrived on a flight from Bangkok. When Kaja Moideen’s bag was opened, onlookers were shocked to find a tiny leopard cub in a basket.

A month after the seizure made global headlines and led Interpol to contact Indian authorities as part of their investigation into global illegal trade in wildlife, another passenger flying in from Bangkok was stopped on suspicion. Among the chocolates and gift items in his luggage was an African horned pit viper, coiled alongside some iguanas and tortoises. The snake, which is listed as near threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), caused a major scare as India does not have anti-venom for it.

Apart from the poisonous reptile, what alarmed authorities was that a 22-year-old student from Chennai was acting as a courier. According to T Uma, deputy director of Wildlife Crime Control Bureau, an investigative agency tasked with curbing illegal wildlife trade in India, the smuggling syndicate is increasingly employing young students with the lure of free international tickets, hotel stay and a few extra bucks.

Rajan Chaudhary, commissioner of Chennai customs under whose tenure the number of seizures has shot up in the past two years, said that couriers are willing to smuggle animals, often endangered and vulnerable species, for as little as Rs 10,000 per trip. “Chennai is well connected to Southeast Asian countries by regular flights that offer cheap airfare which makes it an attractive transit point for wildlife traffickers,” he said.

Chaudhary said officials from Thailand’s Consulate General’s office in Chennai had met him last week, admitting that they had taken note of regular attempts being made to smuggle wildlife species from that country to the southern Indian city and assured him that security would be beefed up at airports to prevent such incidents.

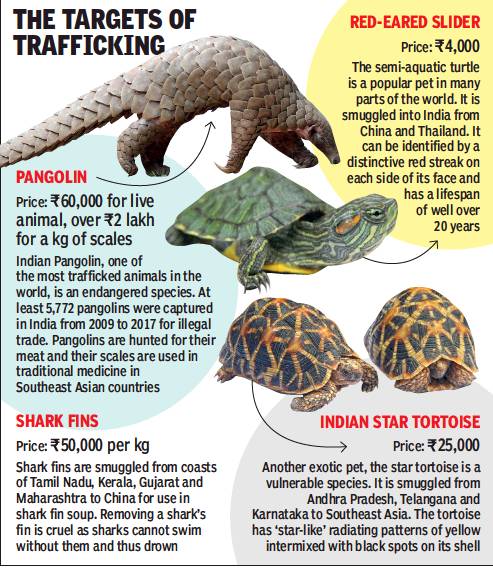

The star tortoise, for one, is often illegally traded on these routes. It is found in abundance in scrub jungles across the southern peninsula and a single such tortoise sells for Rs 25,000 on the illegal market. A 2015 study published in peerreviewed journal Nature Conservation had cited previous research to highlight that Chennai was among the Indian cities from where couriers took these animals on direct flights to Thailand.

Abrar Ahmed, renowned wildlife expert and former senior programme officer at Trade Records Analysis of Flora and Fauna in Commerce-India (Traffic), said that pangolin, star tortoise and sea horse are among the species most at risk. “The Indian pangolin falls under the endangered category in the IUCN Red list of threatened species. It is now one of the most trafficked throughout the world. In 2018, Traffic India had released a study that revealed at least 5,772 pangolins were captured in India from 2009 to 2017 for illegal trade. Pangolins are hunted for their meat and their scales are used in traditional medicine in Southeast Asia,” Ahmed said. He added, “The Patagonian seahorse, one of the three sea horse species that is trafficked for its use in medicine, falls under IUCN’s vulnerable category. The Indian star tortoise is now the most trafficked tortoise worldwide as it is in high demand as a pet.”

Recent seizures in Chennai seem to suggest presence of a well-entrenched smuggling network in the city. In one of the largest hauls, 660kg of sea horses, pipe fish, stingray, sea cucumbers, shark fins and pangolin scales were seized in north Chennai in February. The consignment was valued at Rs 7 crore in the international market. In October last year, 490 star tortoises seized at Kasimedu fishing harbour in Chennai were meant to be smuggled through Thai Air cargo.

While the customs department in Chennai has been seizing star tortoises, sea cucumbers and pangolin scales being smuggled out of the country for years, officials say that there has also been a rise in exotic species being smuggled in. But where the exotic wildlife being smuggled into India is going is anybody’s guess.

It is likely that the exotic species have caught the fancy of affluent Indians who want to flaunt foreign breeds as pets, Chaudhary said. In the recent past, there has been an increase in seizures of red-eared slider turtle being brought in from Thailand and Malaysia. The turtle has gained popularity as a pet as it is supposed to bring luck and prosperity. In India, it is illegal to own a red-eared slider.

T Uma said wildlife smugglers cash in on the loopholes in law. Many species, such as the horned pit viper, are not covered under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, or the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora that regulates all commercial trade. In such cases, the courier is charged under the Customs Act and the Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act for not having a no objection certificate for their “goods”. The courier is then let off after paying a penalty. “We need to add more species under the Wildlife Act to ensure strict action,” Uma said. “Even though couriers are caught redhanded by customs, the link ends there. They usually have no knowledge of the handler or the customer.”

When the 22-year-old Chennai student who acted a courier for the horned pit viper was questioned, he admitted he was supposed to give the bag to someone outside the airport but had no knowledge of who it might be. He was taken outside but no one turned up to receive the bag even after waiting for a considerable time. The man was let off. The snake he brought in was packed off to Thailand. The leopard cub, though, now five months old, is thriving at a Chennai zoo, awaiting translocation to Thailand.

(With inputs from Sandeep Rai in Meerut)

Snares

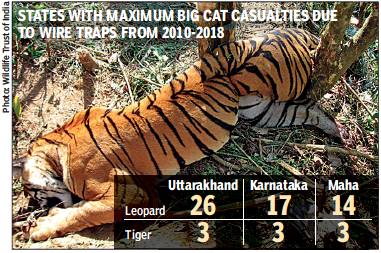

2010-18: tigers, leopards

VIJAY PINJARKAR, May 22, 2019: The Times of India

From: VIJAY PINJARKAR, May 22, 2019: The Times of India

It was a rescue that came too late. For almost two years, a tigress in Maharashtra’s Tipeshwar Wildlife Sanctuary had been carrying a wire noose around her neck. When the tigress was spotted on March 17 this year, her injury had worsened and maggots had collected around the wound. She died hours after she was tranquillised by forest officials in a bid to save her.

A month later, another tigress was found dead — her neck held tight by the cruel coils of a wire snare — in Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve.

Every year, tigers and leopards in India are being killed or injured by snares, a threat that doesn’t register when one lists dangers faced by big cats. In the last nine years, 24 tigers and 114 leopards have suffered slow, agonising deaths in these traps. Little has been done to tackle the menace. More troubling is the fact that in the latest tiger deaths, the snares were in core areas of the reserves.

Anti-snare exercises should be part of patrolling: Experts

Sometimes it is poachers who lay metal jaw traps to lock unsuspecting animals, at other times it is local communities who use wire noose snares to kill big cats preying on their livestock.

The Wildlife Protection Society of India, a non-profit working to combat poaching and illegal wildlife trade, has monitored big cat deaths due to snares for the period between 2010 and 2018. Apart from the deaths, there were many injuries to animals reported.

Experts said threat from snares needs to be immediately addressed and the forest department should make antisnare exercises with the use of metal detectors a regular part of patrolling.

Kishor Rithe from Satpuda Foundation, which works for tiger conservation, said they had prepared a standard operating practice to deal with wire snares in 2012 but it has since been gathering dust.

“The use of metal detectors in tiger reserves during patrolling could be the first line of defence and help weed out such snares,” said Rithe.

Jose Louies, deputy director and chief, wildlife crime control division and communications, Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), said thousands of animals fall prey to wire snares but the issue is only highlighted when a tiger or a leopard is caught.

Louies said that earlier poachers used creepers and bamboo traps to kill wild animals. Now binding wires used in buildings, wires from solar fence and bike clutch cables are preferred because these are low on investment, easy to carry, hide, install and effective in capturing a wide variety of animals. “Once installed in an animal path or forage, they will go unnoticed,” he said, adding that anti-snare walks could help prevent poaching in fringe areas.

“WTI and the Karnataka forest department have seized over 2,000 snares since 2012. In Karnataka’s Bandipur tiger reserve, we took the help of people from fringe villages to collect initial intelligence on snaring,” said Louies. In Karnataka, anti-snare drives are now part of patrolling exercise.

In Maharashtra, forest officials admitted they have regularly seized snares near TATR. Divisional forest officer Deepak Chondekar told TOI, “When I was posted in Shivni in 2010, I seized over 100 wire traps. In most such cases, there is no prosecution.”

The death of the tigress in Tadoba did spur authorities into action. Four suspected poachers have since been arrested and frequent anti-snaring drives are being conducted.

Maharashtra principal chief conservator of forests (wildlife) Nitin H Kakodkar said, “Periodic anti-wire snare operations will be intensified in park areas with special focus on the peripheral areas.”