Architecture: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Himachal Pradesh

Kathkuni houses

Siddarth Banerjee, Sep 7, 2025: The Times of India

From: Siddarth Banerjee, Sep 7, 2025: The Times of India

From: Siddarth Banerjee, Sep 7, 2025: The Times of India

Having lived all his life in Himachal Pradesh’s picturesque Tirthan valley, famed for its towering deodar forests, homestays and trout fish, Khub Ram (52) says he has never seen a traditional stone-and-timber Kathkuni house being built next to a river. “Perhaps that is why the floods in July and August did not damage them much. They were never in the way,” says Ram, an apple-grower from the remote Tindra village in Kullu’s Banjar tehsil.

These days, Ram is busy sending his apple harvest to the Banjar fruit market. For a month, he couldn’t — heavy rain, cloudbursts, flash floods and landslides had cut off roads and ravaged Himachal, leaving at least 360 dead. Yet his family still lives on the same spot where his great-grandfather built their home 150 years ago. “I renovated it 20 years back, but half the wood and stone came from the original structure,” he adds.

Ram’s experience is not an exception. Across Himachal, families living in Kathkuni homes — kath meaning wood and kuni meaning corner — narrate similar stories of endurance. Ojasvi Jagithta, an assistant professor of architecture at Kangra’s Rajiv Gandhi Government Engineering College, talks of one exception — an aunt who lost her Kathkuni home in a flood in 1970s Shimla. “But that was because it was built near farmland,” recalls Jagithta, speaking from her office with the mighty Dhauladhars framed in the window behind.

Her words ring true this monsoon. As torrential rain wreaked havoc across Himachal and swept away rows of concrete-and-brick houses, structures made in the state’s fast-fading indigenous style once again stood firm, not because they resisted nature, but blended in with it.

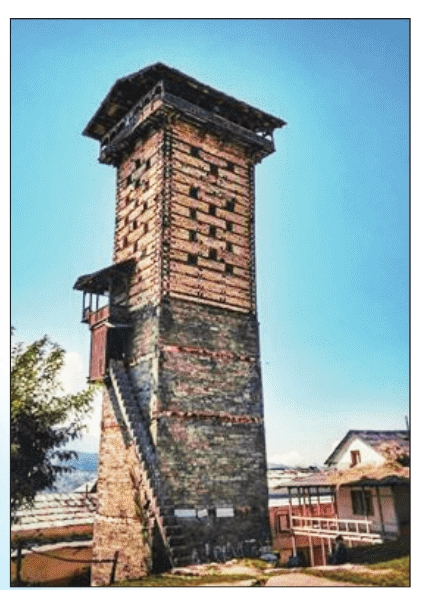

Rahul Bhushan, whose collective, NORTH, specialises in vernacular architectures, calls this resilience a result of “indigenous intelligence”. His collective operates out of a century-old Kathkuni building he has taken on lease in Naggar — a town famous for the 15thcentury Naggar Castle and the Nicholas Roerich Art Gallery. Perched like an eagle at 1,800 metres, Naggar commands a sweeping view of the Kullu valley from the left bank of the Beas — perhaps why it remained the capital of the erstwhile Kullu kingdom for nearly 1,400 years.

Surrounded by sketches of Kathkuni homes at his workshop, Bhushan says old settlements were always raised on rocky strata, safe from sudden waters. “These buildings guide water. Elevated plinths, sloping roofs and porous courtyards let rainwater flow naturally.”

Deepu Asheibam, an architect with specialisation in urban and regional planning from CEPT University, Ahmedabad, says the walls of a Kathkuni structure may also, in case of a flood, allow water to drain through stacked stones because no mortar is used.

“One disadvantage, though, would be the rotting of wood if there is prolonged exposure to water,” he says.

Kathkuni’s endurance is visible across Himachal: the 13th-century Bhimakali Temple in Sarahan, the 14th-century pagoda-style Prashar Lake temple, and the 12-storey Chehni Kothi in Banjar’s Chehni village, which has survived for over 350 years. In contrast, modern brick-and-cement structures, many of which dot riversides, lack the flexibility that comes with stone and wood.

Damage to these modern structures, a fallout of the hill state’s rapid urbanisation, was most visible in the flash floods that hit Thunag, 34km from Khub Ram’s house, in late June. A report by citizens’ collective Himalayan Niti Abhiyan estimated losses at over Rs 150 crore, linking the disaster to encroachment, unregulated construction, and blocked natural drainage.

For Jagithta, centuries-old techniques like Kathkuni — and others in Himachal such as Dhajji Dewari in Kullu and Thatara in Chamba — in- volved more foresight than what is applied these days. “Though we can now study the geology and hydrology of a site, we are constructing anywhere, be it watershed areas, refuge gaps, or faulty zones,” she says. “Back then, a village’s site planning was such that all the surface runoff would be directed to water channels without affecting the structures’ foundations.”

Bhushan points out that the foundation of a Kathkuni building rests on wide stone plinths, often without deep Illustrations inspired from “ Prathaa: Kath-Khuni Architecture of Himachal Pradesh ” , authored by Bharat Dave, Jay Thakkar and Mansi Shah; and (above) CEPT University's SWS 2019 excavations that destabilise slopes. “In contrast, RCC (reinforced cement concrete) foundations cut harshly into fragile mountain soil.”

The same features that make Kathkuni resilient also make it difficult to replicate today. Stricter laws on tree felling and stone quarrying are among the top challenges. Constructing a Kathkuni house involves twice the cost of a cement one. A 2019 estimate by Asheibam put the cost of a contemporary threeroom house at Rs 4.5 lakh, and that of a Kathkuni house at Rs 10.9 lakh. Varun Bharti, who owns the famous Raju Bharti Guest House in Gushaini village near Jalori Pass in Kullu, says timber has to be sourced from the forest department, and finding the right size requires an exhaustive search. “That is why a lot of the new constructions have more stone than timber,” says Bharti, who also owns a Kathkuni home.

The thicker walls of a Kathkuni structure are another drawback, Asheibam says, as they restrict floor space . But these buildings can easily be repaired due to their modular nature. “In an RCC building, everything tends to break and turn into debris. In a Kathkuni, stones can be easily reused, and wood can be replaced or repaired,” he says.

Bhushan justifies the higher cost of a Kathkuni structure by its longevity and minimal maintenance. “RCC, even in its best form, lasts 70-80 years. It needs machines, cement, contractors, and endless expenses to repair damp walls and peeling paint,” he says.

Bhushan is batting for evolution of Kathkuni and other indigenous architectures of the Himalayas. “Treated timber, waterproofing of layers, hybrid joineries — these can all strengthen it,” he says. Jagithta, too, argues for an approach that mixes new-age expertise with old wisdom.

“Like earlier times, we can no longer build only on higher areas far from water channels because of urban pressure. There are, however, ways of dealing with all sites differently. Vernacular architectures have developed according to the terrain, available material, and local lifestyles,” she says. “Modernvernacular is the way forward.”

Ram falls back on the simple wisdom of the mountains. ”There is a saying in our area: Ek naddi agar ek jagah sey pehlay behti thi, woh ek din wahaan wapas aayegi (If a river used to flow on a stretch earlier, it will return to that course in future),” he says.