Article 39(b) of the Constitution of India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Redistribution of private properties for greater common good

2024 Apr: SC to deliberate

Dhananjay Mahapatra, April 24, 2024: The Times of India

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra, April 24, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi : A nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court commenced the process for interpretation of Article 39(b) of the Constitution to determine whether this directive principle of state policy provision allows govt to treat and redistribute privately owned properties under the garb of “material resources of the community” for greater common good.

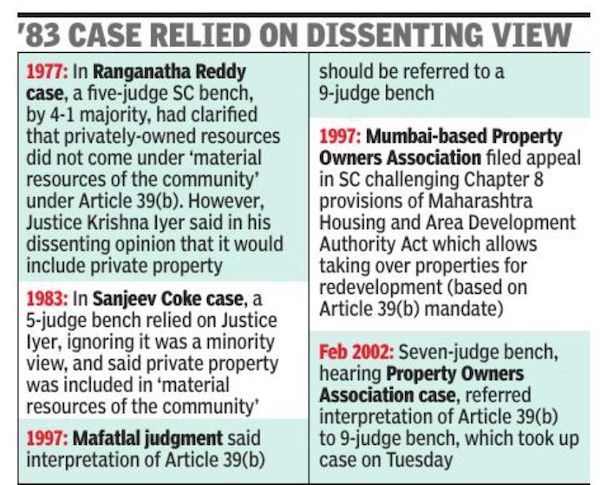

The interpretation by a bench comprising Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud and Justices Hrishikesh Roy, B V Nagarathna, S Dhulia, J B Pardiwala, Manoj Misra, R Bindal, S C Sharma and A G Masih stems from Justice V R Krishna Iyer’s dissenting view in Ranganatha Reddy case of 1977 that community resources included private properties and the conflation of the two in later judgments, leading to the matter being referred on Feb 20, 2002, for interpretation by a nine-judge bench. Article 39(b) provides that the state shall direct its policy towards securing “that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good”.

Senior advocates Devraj, Zal Andhyarujina and Sameer Parikh argued that community resources could never include privately owned properties. Arguments will continue on Wednesday.

Why SC’s nine-judge bench needs to interpret Art 39(b)

The advocates termed Justice Iyer’s view a reflection of his Marxist socialist ideology which had no place in a democratic country governed by a Constitution giving primacy to fundamental rights of citizens.

Though the question is old, it is reverberating in current politically-surcharged atmosphere after Rahul Gandhi’s speech at a public meeting on Saturday where he said, “First, we will conduct a caste census... to know the exact population and status of backward castes, SCs, STs, minorities and other castes. After that, financial and institutional survey will begin. Subsequently, we will take up the historic assignment to distribute the wealth of India, jobs and other welfare schemes to these sections based on their population.”

PM Modi quickly reacted to this by alleging that Congress will take away private wealth of citizens for redistribution and juxtaposed it with the 2006 speech of exPM Manmohan Singh.

Solicitor general Tushar Mehta said the sole question before the court was interpretation of Article 39(b) and not Article 31C, the provision which provides safe harbour to laws enacted in pursuance of the directive principles, whose validity as it existed prior to the 25th constitutional amendment in 1971 has been upheld by a 13-judge bench in Kesavananda Bharti case.

CJI Chandrachud agreed and explained why Article 39(b) needed to be interpreted by a nine-judge bench. “The reason for the exercise before the nine-judge bench is that though majority in the Ranganatha Reddy case in 1977 clarified that material resources of the community do not include private property, a fivejudge bench in Sanjeev Coke in 1983 relied on Justice Iyer ignoring that it was a minority view,” he said.

“In the meantime, SC in Mafatlal Industries case in 1997 opined that Article 39(b) needed interpretation by a ninejudge bench,” the CJI said. In the Mafatlal case, SC had said it was difficult to accept the broad view that material resources of the community under Article 39(b) covered what is privately owned.

The bench asked how excess agricultural land was distributed among poor peasants in the 1960s. Devraj said no one questioned the state’s power to acquire land for public purposes after paying a fair compensation to the owner of the land. Land ceiling laws were passed by states to determine excess land accumulated by zamindars and such excess land was then redistributed, he said.

“But if govt wants to take away my property and distribute it to the poor, then I would be left with no money as my fees would be taken away and paid to poor people,” he said in a lighter vein.

Does Art 39(b) allow govt to take over your property?

Aditya Prasanna Bhattacharya & Aditya Phalnikar, May 16, 2024: The Times of India

Amid polls to constitute the 18th Lok Sabha, the governing party and the opposition have clashed over a critical question — how much inequality is India willing to tolerate? In its manifesto, Congress has promised to conduct a nationwide caste census to determine the socio-economic conditions of various caste and sub-caste groups. Congress functionaries have taken umbrage to the unfair concentration of wealth in the hands of a select few individuals. BJP has hit back, accusing Congress of appeasement politics and termed this exercise an attempt to extract private wealth from individuals and redistribute it among minorities.

The issue is philosophical: to whom do a country’s material resources belong? As this debate rages on in election rallies and across TV newsrooms, the Supreme Court is quietly preparing to answer this question. While deciding a seemingly innocuous set of property disputes originally filed in 1992, the SC has felt the need to re-interpret Article 39(b) of the Constitution, a directive principle of state policy which urges the state to make policies to ensure “that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as to best subserve the common good”.

Not Just An Academic Question

Generally, directive principles of state policy are unenforceable by a court of law. A member of the Constituent Assembly even described the entire part as a ‘dustbin of sentiment’. But Article 39(b) is different. It is underwritten by Article 31C — which provides that a law made by Parliament in furtherance of Article 39(b) is not invalid even if it violates fundamental rights such as equality and freedom of trade. It is worth mentioning that the linkage between the two provisions is also an issue before the Supreme Court in this very case.

The Trajectory Of The Case

Of course, the expression ‘material resources’ must include public resources. The question is simple: does it include private resources as well?

What Are The Possibilities?

A recent study by the World Inequality Database has stated that wealth inequality in India is now higher than what it was during British rule in India. In light of this, Parliament could potentially enact a ‘wealth tax’ where all citizens with a certain net worth would be taxed 2% of their wealth.

Challenging the law because it violates fundamental rights such as equality, life and personal liberty, and freedom of trade would be futile, because Article 39(b), backed up by Article 31C, would kick in.

Another example includes a law to acquire all privately held forest land across the country and distribute it among tribal communities who are displaced by climate change, infrastructure projects, internal conflict etc. A mere reference in such an Act to Article 39(b) will save it from being struck down.

The Real Implications

The implications of this case go beyond the immediate political debate. Its significance lies in how the apex court interprets the constitutional guarantee of equality, and how much power it gives to the state to fulfil this guarantee. A restrictive interpre- tation will assign the role of reducing inequality to the private market, hoping that ‘invisible hand’ will reach everyone. A broader interpretation will give greater powers to the state to interfere in private affairs to ensure proper redistribution of wealth.

Underlying this provision is an assumption that the state may be better capable of ensuring equality. This may be true in some cases, but very false in others.

A Gandhian Vision Of Article 39(b)

During the hearings, CJI Chandrachud stated that Article 39(b) could not be interpreted in a purely communist or socialist sense. He seemed to detect a Gandhian flavour to the provision. It is hence likely that the SC will give us a more nuanced interpretation of Article 39(b). Private property may not be wholly excluded, but certain kinds of private property may be declared to be held in trust.