Assam: The citizenship/ foreigners/ illegal migration issue

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

History

Ahom rule, the 1800s, the 1900s

Samrat, June 3, 2021: The Times of India

In Ahom territories, over a period of centuries, the original Tai Ahom language and religion of the kings, nobles and priestly classes gradually gave way by the seventeenth century to Hinduism and the Assamese language of Upper Assam, where they ruled. With the end of the Ahom rule and the advent of the British Raj, the language of power changed. At the start of their rule in 1826, the British East India Company Raj only annexed the old Koch kingdom’s territories in Lower Assam to their adjacent territory, the Bengal Presidency, which they ruled from their capital in Calcutta. Between 1838-42, Upper Assam corresponding to the Ahom and Motok kingdoms was also annexed.

During this period a vigorous debate was raging on the question of which language was to be used as the language of administration of British India. The British had initially continued with the Mughal court language, Persian, as their official language, and up until 1837 this was the language of government of the new rulers. In January 1838, the Judicial and Revenue Department of the British Company Raj ordered that ‘in the districts comprised in the Bengal division of the presidency of Fort William, the vernacular language of those provinces shall be substituted for the Persian in judicial proceedings, and in the proceedings relating to the revenue, and the period of twelve months from the first instant shall be allowed for effecting the substitution.’

The Bengal Presidency then stretched from the North-West Frontier Province to Burma. Until 1874, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal administered five provinces: ‘Bengal Proper, Behar, Odisha, Chota Nagpore and Assam’. Henry Beverley, the author of The Census of Bengal published in 1874, provided a brief description of each of these territories and their inhabitants: ‘Assam is the valley of the upper Brahmapootra, with such of the hill territory on either side as lies within the British frontier. It is inhabited, though sparsely, by a variety of races. The Assamese language appears to be merely a dialect of Bengali.’

The combination of changing language policies, substituting vernaculars for Persian, and the British administration’s notion that Assamese was a dialect of Bengali, which persisted until many decades after 1838, led to Bengali becoming the language of lower courts and bureaucracy in Assam. This is the source of the Assamese–Bengali linguistic clash. It is remembered with anger to this day in Assam, as an imposition of Bengali crafted by the Bengali clerks, rather than the British rulers. For this reason, Bengali-speakers alive today are viewed by many staunch Assamese nationalists in much the same way that Muslims are viewed by Hindu nationalists.

There are no records of major protests immediately after the imposition of Bengali in Assam. That was to happen only later, through the efforts of the two American Baptist missionaries, Nathan Brown and OT Cutter, who had arrived in 1836. They had brought with them the first printing press and had set about preaching the Bible, initially among the Singphos and Khamptis, who chased them and the British rulers out of Sadiya. Brown and Cutter then turned their attention to the Brahmaputra Valley and began their missionary task by publishing literature in the local dialect of their new base, Sivasagar, not far from the Naga Hills. Here they began to have greater success, with the Sivasagar tank next to the Siva Dol temples being used for baptisms. From 1846, they also began to publish Orunodoi, the first newspaper in Assamese, to propagate the news and views of their choice. The writers who wrote for Orunodoi under Brown’s editorial leadership were people like Anandaram Dhekial Phukan, Hemchandra Barua and Gunabhiram Barua, remembered now as the founders of modern Assamese literature and vocabulary.

The Baptist Missionaries, who had already translated the Bible into what they considered pure Assamese (there was an older translation into Assamese which they rejected), led the campaign against the imposition of Bengali on Assam. The mission press published the first Assamese grammar, compiled by Reverend Nathan Brown, and the first dictionary, put together by the Reverend Miles Bronson.

The missionaries also petitioned the British government on behalf of the Assamese language. When AJ Moffat Mills, a judge, arrived in Assam in 1853 to prepare a report on the revenue administration, the missionaries presented him with a petition on the issue of language. Mills was greatly impressed. ‘Assamese is described by Mr Brown, the best scholar in the province, differing in more respects than agreeing with the Bengalee, and I think we made a great mistake in directing that all business must be transacted in Bengalee, and the Assamese must acquire it,’ he wrote.

However, government policy has always been slow to change, and nothing came of Mills’ observations. Nonetheless, Bronson kept up the efforts after Brown’s departure from Assam. In 1872, he submitted a memorandum titled ‘Humble memorial of the Assamese Community of Nowgong, Assam,’ signed by 216 persons of whom he was the leader. By this time, a reorganisation of the Bengal Presidency was already on. It was a vast and unwieldy territory, and a gradual process of reorganising it had been on since 1836 when the North-Western Provinces bordering Afghanistan were separated and placed under a lieutenant governor. A spate of Lushai raids on Cachar, which was then in Dhaka Division, prompted a relook at the North Eastern end of the British Indian Empire as well. In 1874, the British administration finally decided to reorganise Bengal by creating a chief commissionerate for the North East Frontier. In the ensuing redrawing of maps, Goalpara, Cachar and Sylhet, the Garo, Khasi and Jaintia Hills, the Naga, and subsequently also the Lushai Hills, were merged with Kamrup and the erstwhile Ahom and Motok territories to create the province of Assam. The logic broadly followed was dictated by commercial interests – as the Viceroy Lord Mayo had declared it would be unwise to split the tea-growing country, this led to the inclusion of Sylhet and Cachar, which were then part of Bengal. Goalpara, which had been part of Bengal since Mughal times, was also transferred to Assam.

The inclusion of these predominantly Bengali-speaking areas brought a large Bengali population into Assam. The area of the newly created Chief Commissionership of Assam was 41,798 square miles and its total population was 41,32,019, out of which the three districts of Sylhet, Cachar and Goalpara, which were transferred from Bengal to the new province, accounted for 13,623 square miles and a population of 27,02,327, as per the census of 1872.46

This sharpened the divide between the Bengali and other identities; literacy was then not widespread, and the relatively more literate Bengalis, mainly caste Hindus from Sylhet, came to dominate jobs in the new administration, to the chagrin of the caste Assamese, who were their rivals for the same jobs. Moves to get rid of them manifested in identity politics. The competition for dominance sharpened once electoral politics entered the picture when elections with limited franchise were introduced after the Assam Assembly was established, before Partition and independence, in 1937.

The insecurities of competition for jobs, land and resources have fuelled different waves of identity politics in Assam from its formation till date. The first separation, that of Assam from Bengal, was followed by multiple separations of smaller territories and identities from Assam. After the overbearing presence of Bengalis had been whittled down to size, the tribal groups rebelled next against Assamese domination. The Naga Hills became Nagaland in 1963. The Garo, Khasi and Jaintia Hills broke away and became the state of Meghalaya in 1971-72. The Lushai Hills became the union territory of Mizoram in 1972 and was upgraded to a state in 1987. Arunachal Pradesh, earlier known as North East Frontier Agency, followed a similar trajectory. That’s not all. There are long-running movements for a separate Bodoland state, a Dimarji of the Dimasa Cacharis, and a Karbi state. The Koch Rajbongshis have a demand for a state that would include parts of Assam and West Bengal. There have also been occasional murmurs from the Bengali-speaking Barak Valley areas of Assam in favour of becoming a separate state.

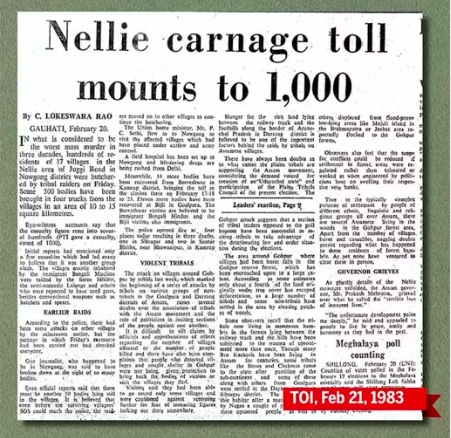

The issue of who belongs in Assam is still not settled. It is a question that has led over the years to many massacres. After Independence, starting 1960, there were riots against the Bengali-speaking populations, mainly directed against the Hindu Bengalis who had come as Partition refugees fleeing riots in East Pakistan. The slogan of the rioters then was ‘Bongal kheda’, meaning ‘drive out the Bongals’, a term which originally meant outsiders but by then had come to mean Bengalis. The Assamese fears of Bengali domination led in 1979 to a movement called the Assam Agitation, aimed at evicting ‘foreigners’ with the slogan of ‘bidekhi kheda’, meaning ‘drive out the foreigners’. The foreigners targeted were once again Bengalis, Hindu as well as Muslim, who were seen as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. In 1983, in a place called Nellie upriver from Guwahati, mobs armed with bows and arrows, machetes, sticks, and other such weapons surrounded and massacred at least 2,191 Bengali Muslim men, women and children overnight. Not a single person was ever charged with any crime for the thousands of murders.

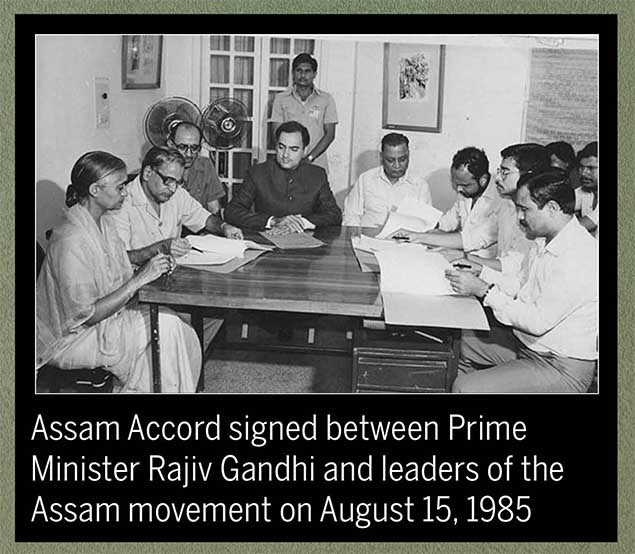

In 1985, an accord was signed by the Government of India with the All Assam Students Union and the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad which had led the Assam Agitation. A key clause of the accord related to the detection, deletion from electoral rolls, and deportation, of foreigners who had entered Assam on or after 25 March 1971 – the day that Operation Searchlight in neighbouring East Pakistan kicked off a genocide, one of the worst in world history, in which somewhere between one and three million Bengali civilians were massacred by the Pakistan military. The Assam Accord’s cut-off date was thus selected so as to exclude those who fled the Bangladesh genocide that began from March 25.

Unfulfilled promises of implementation of the Assam Accord by governments since 1985 led, more than thirty years later, to the legal activism that kicked off the attempt to draw up a National Register of Citizens specifically for Assam.

Excerpted with permission from Braided River (published by HarperCollins India)

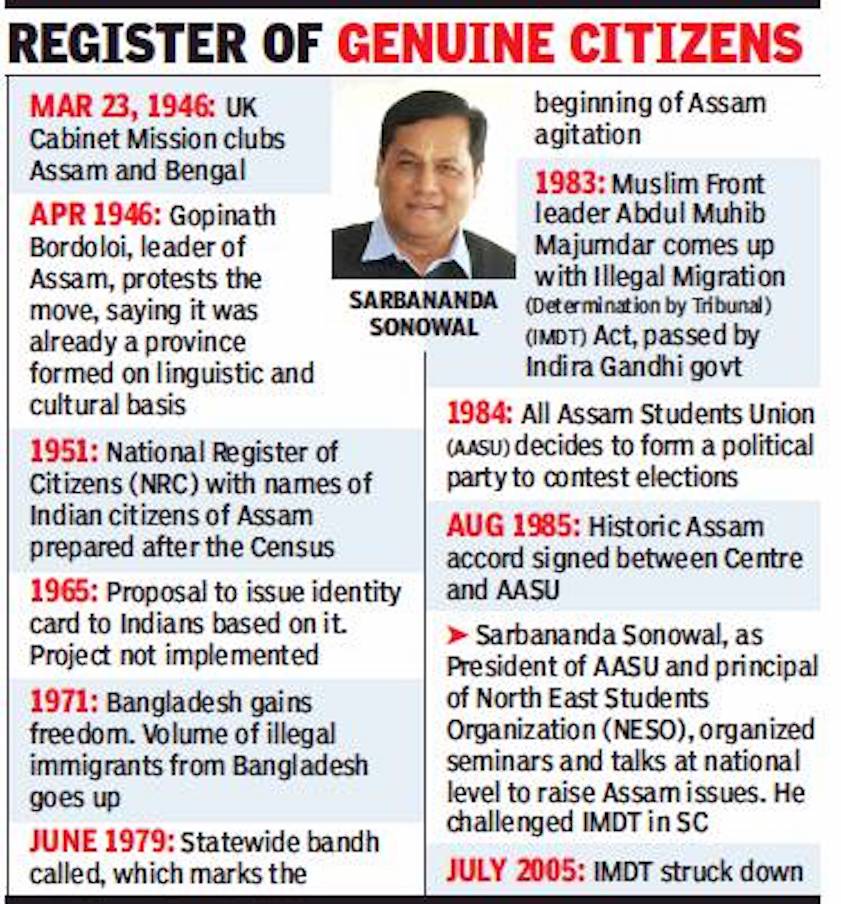

Chronology: 1948-2005

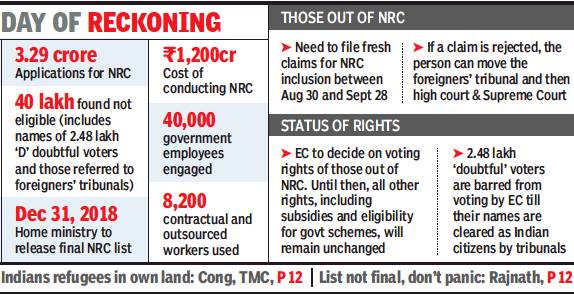

From: ‘No one will be treated as foreigner if name not in NRC final draft’ July 30, 2018: The Times of India

With the second draft of Assam’s National Register of Citizens (NRC) coming out on Monday, CM Sarbananada Sonowal tells Neeraj Chauhan nobody will be treated as a foreigner if his/her name is not on the draft list. Excerpts

The NRC second draft will be out. What is the government’s strategy to deal with the situation and how will you make sure that all sides are satisfied?

When we came to power two years ago, we promised to free the state from illegal immigrants. Updating the NRC is an important tool to identify illegal migrants. We also believe that a flawless NRC will be the primary security shield for people living in the Barak-Brahmaputra valleys, hills and plains of Assam. One must remember that the NRC to be published is only a draft and genuine citizens who are left out from the draft NRC need not panic as they could still get their names enrolled in the final NRC.

What about the people who couldn’t prove their citizenship once the NRC is out tomorrow?

No one will be treated as a foreigner if his or her name does not appear in the NRC draft. Once the complete draft is out, ample opportunity will be given to applicants to prove their eligibility.

Are you anticipating violence in the state once the list is out?

I have faith in the political maturity of the people. We all have seen how the people acted when the first draft NRC was published. I am sure that this time also, people of Assam will display similar maturity.

Has any decision been taken on deportation of illegal immigrants once the list is out? Is there a plan?

The final NRC, which will be out after going through a legal process under the supervision of the Supreme Court, will provide us a tool to distinguish between a bona fide Indian and a foreigner. So, our priority is to identify foreigners. What steps government takes will come next.

What are your comments on the Citizenship Amendment Bill, which proposes to give citizenship to religious minorities from Bangladesh, Pakistan etc.

The Centre has assured that before taking any step, the people of Assam will be taken into confidence.

1950 onwards: Congress govts mute spectators to illegal migration

Dhananjay Mahapatra, August 6, 2018: The Times of India

Publication of the draft National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam made Mamata Banerjee warn of “civil war” if such an exercise was repeated in West Bengal. Banerjee whipped out the regional card and issued a veiled threat by asking what would happen if one state did not want residents of another state in its territory.

Congress and BSP too have criticised the NRC for different reasons. But what did the NRC do, except attempting to find out who were Indians and who had migrated illegally. It was the influx of illegal migrants which required updating of the NRC. We will first talk about the problem of illegal migrants and the NRC later.

Chronic inaction since 1950 stalled updating of the NRC and identification of illegal migrants. History is witness to Congress governments closing their eyes to massive influx of illegal migrants into Assam, threatening to reduce Assamese to the status of minority.

Parliament acknowledged the problem in 1950 and enacted the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act as it felt “during the last few months, a serious situation had arisen from immigration of a very large number of East Bengal (now Bangladesh) residents into Assam… disturbing the economy of the province, besides giving rise to a serious law and order problem”. The Centre was empowered to expel illegal migrants, but without any tangible action, the problem was allowed to fester.

In September 1944, Sheikh Mujibur Rehman Khan and economist M Sadeq published a booklet ‘Eastern Pakistan: Its Population, Delimitation and Economics’ which said, “Because Eastern Pakistan must have sufficient land for its expansion and because Assam has abundant forests and mineral resources, coal, petroleum etc, Eastern Pakistan must include Assam to be financially and economically strong.”

Taking a leaf out of this booklet, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s 1967 book ‘Myth of Independence’ said, “It would be wrong that Kashmir is the only dispute that divides India and Pakistan, though undoubtedly the most significant... One at least is nearly as important as Kashmir dispute, that of Assam and some districts of India adjacent to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).”

The Indo-Pak war of 1971 and birth of Bangladesh saw Assam get choked with unmanageable numbers of Bangladeshi migrants. Successive Congress governments turned a blind eye to this massive influx. The state’s students did not. Between 1971 and 1991, Assam’s Hindu population grew by 41% but that of Muslims registered a 77% increase. Massive students’ agitation for six years forced the Rajiv Gandhi government to sign the Assam Accord on August 15, 1985, promising to detect and deport those had who illegally entered Assam after 1971.

The accord was a dead document from its birth. For, in 1983, the Congress government enacted Illegal Migrant (Determination by Tribunals) Act that made detection impossible. Till August 2003, inquiries against 3,86,249 persons were initiated, a minuscule 11,636 were declared illegal migrants and only 1,517 expelled. Congress now claims that UPA-1 and UPA-2 governments deported more illegal migrants between 2004-2014 than any other government.

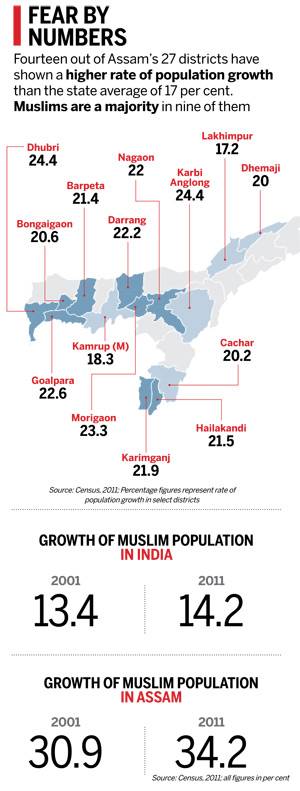

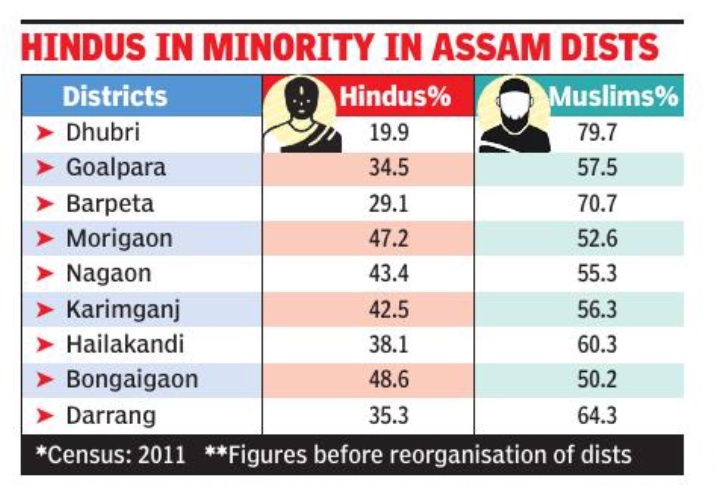

In 1998, Assam governor Lt Gen S K Sinha sent a report to the Centre highlighting how Dhubri, Goalpara, Barpeta and Hailakandi had become Muslim majority districts and Nagaon, Karimganj and Morigaon districts would soon become so because of unabated illegal influx of Bangladeshi migrants.

The governor’s prophecy came true. As per the 2001 census, Muslim majority districts in Assam were Barpeta (70.4% Muslims), Dhubri (79.67%), Karimganj (56.36%), Goalpara (57.52%), Hailakandi (60.31%), Nagaon (55.36%), Bongaigaon (50.22%), Morigaon (52.56%) and Darang (64.34%).

The governor had also warned, “There is a tendency to view illegal migration into Assam as a regional matter affecting only the people of Assam. It’s more dangerous dimensions of greatly undermining our national security is ignored. Long cherished design of Greater East Pakistan/Bangladesh, making inroads into strategic land link of Assam with the rest of the country, can lead to severing the entire land mass of the north-east, with all its rich resources from the rest of the country. They will have disastrous strategic and economic consequences.” Did any ruling party at the Centre view the report with the seriousness it deserved?

Sinha’s report said illegal migration, which was the core issue behind the students’ agitation, threatened to reduce Assamese people to a minority in their own state and a prime contributing factor behind increased insurgency. “Yet, we have not made much tangible progress in dealing with this all important issue,” he had said, hinting at IMDT Act’s ineffectiveness to detect illegal migrants.

Sarbananda Sonowal moved the Supreme Court in 2000 and challenged validity of IMDT Act. In August 2000, Prafulla Mahanta’s AGP government told the SC in an affidavit that the Centre was not heeding its repeated requests for repeal of IMDT Act because of its ineffectiveness.

In August 2001, the Tarun Gogoi government sought to withdraw the Mahanta government’s stand and vigorously defended IMDT Act — first through Kapil Sibal and later through K K Venugopal — saying Congress was committed to oppose any move to repeal the Act. It sought dismissal of Sonowal’s petition.

The SC quashed IMDT Act in 2005 and termed it “the biggest hurdle and the main impediment or barrier in identification and deportation of illegal migrants”. It ordered their detection through the Foreigners Tribunal, saying it had proved more effective in dealing with illegal migrants in neighbouring N-E states.

The SC had said, “There can be no manner of doubt that the state of Assam is facing ‘external aggression and internal disturbances’ on account of largescale illegal migration of Bangladeshi nationals. It, therefore, becomes the duty of the Union of India to take all measures for protection of the state of Assam from such external aggression and internal disturbances as enjoined in Article 355 of the Constitution.”

The SC ordered transfer of all cases before IMDT to the Foreigners Tribunal. But the UPA government was in no mood to obey the SC verdict. In February 2006, it passed the ‘Foreigners (Tribunal) Amendment Order’ making detection of illegal migrants through Foreigners Tribunals inapplicable to Assam.

Sonowal again knocked at the SC’s doors. In December 2006, the SC quashed the order and rapped the UPA government on the knuckles. It said instead of strictly implementing the 2005 judgment, the Centre “lacked will” to ensure that “illegal migrants are sent out of the country”. Yet again, the SC had to remind the UPA government of its duty under Article 355 to protect the integrity of the nation.

In 2009, another PIL by NGO ‘Assam Public Works’ in the SC sought updating of the NRC. Hearing in the PIL picked up only after a bench headed by Justice Ranjan Gogoi, of which Justice R F Nariman later became a part, zealously took up the issue from August 4, 2014. The bench bound the authorities to the deadlines for stagewise preparation of NRC.

On November 30 last year, when it was about to fix a deadline for draft NRC publication, the BJP-led government through attorney general K K Venugopal, who as a senior advocate and appearing for Tarun Gogoi government had stoutly defended IMDT Act, pleaded that it was the executive’s job to set deadline for draft NRC publication and the SC should not encroach into its domain.

The SC discarded the argument and said it was too late in the day to raise the argument about judiciary encroaching into the executive’s domain when in the past three years of monitoring, the Centre had never raised objection. Last week, it said those 40.07 lakh persons not figuring in the draft NRC would get a fair chance to seek inclusion and that the entire process would soon be taken to its logical conclusion, that is the final NRC.

Will it serve the purpose? Will it help the Assamese rediscover their emotional connect with their rich cultural heritage? No one knows. But politicians who warn of ‘civil war’ exhibit their ignorance about mental trauma undergone by the Assamese people because of the worrisome ground situation, which was allowed to fester and become an incurable psychological and physical wound.

Issues as in 1971

[ From the archives of The Times of India]

Dhananjay Mahapatra

How illegal immigrants morphed into an invaluable vote-bank

It can happen only in India, where vote-bank politics scores decisively over national interest and issues relating to India’s sovereignty. How else can one explain the cunningness shown by the Centre and the Assam government to disregard the remedial measures suggested by two screaming Supreme Court judgments, which highlighted the demographic aggression faced by Assam from incessant influx of illegal migrants?

In 1971, India was complaining in the UN about the aggression it faced from the huge population shift that was taking place from East Pakistan to its northeastern part. Strangely, 40 years later, the illegal migrants have become an invaluable vote-bank for certain political parties, which hedge the question of their identification and deportation, despite clear directions from the apex court in two rulings in 2005 and 2006.

In 1971, the Sixth Committee of General Assembly was debating to define “aggression”. India’s representative Dr Nagendra Singh voiced serious concern about the incessant flow of migrants from East Pakistan into India and termed it as an aggression to unnaturally change the demographic pattern. Surely, India was preparing a ground for lending active military support to Mukti Bahini in the creation of Bangladesh. Dr Singh supported Burma (now Myanmar), UK and others and said a definition of aggression excluding indirect methods would be incomplete and therefore, dangerous. “For example, there could be a unique type of bloodless aggression from a vast and incessant flow of millions of human beings forced to flee into another state. If this invasion of unarmed men in totally unmanageable proportion were to not only impair the economic and political well-being of the receiving victim state but to threaten its very existence, I am afraid, Mr Chairman, it would have to be categorized as aggression,” he said.

“In such a case, there may not be use of armed force across the frontier since the use of force may be totally confined within one’s territorial boundary, but if this results in inundating the neighbouring state by millions of fleeing citizens of the offending state, there could be an aggression of a worst order,” he had said while arguing for a broader meaning of aggression to include unmanageable influx of migrants. The illegal migration did not subside even after Bangladesh came into being. A sixyear violent agitation against illegal migrants led to signing of the Assam Accord in 1985 between Assam student leaders and then PM Rajiv Gandhi. It promised a comprehensive solution to the festering problem. In 1998, the then Assam governor sent a secret report to the President informing that influx of illegal migrants from Bangladesh continued unabated into the state, perceptibly changing its demographic pattern and reducing the Assamese people to a minority in their own state. It had become a contributory factor for outbreak of insurgency in the state, he said.

The SC in the Sarbananda Sonowal [2005 (5) SCC 665] case quoted from the governor’s report to say, “Illegal migration not only affects the people of Assam but has more dangerous dimensions of greatly undermining our national security. ISI is very active in Bangladesh supporting militants in Assam. Muslim militant groups have mushroomed in Assam. The report also says that this can lead to the severing of the entire land mass of the northeast with all its resources from the rest of the country which will have disastrous strategic and economic consequences.”

The political game over illegal migrants came to the fore in 2000. The AGP government in August 2000 presented disturbing statistics to the SC — Muslim population of Assam went up by 77.42% between 1971 and 1991 while Hindu population increased only by 41.89%. In September 2000, this affidavit was quickly withdrawn by the Tarun Gogoi government immediately after coming to power. The Gogoi government also defended continuance of Illegal Migrants Determination through Tribunal (IMDT) Act, repeal of which was sought by the AGP government on the ground that it was totally ineffective in identifying illegal migrants.

The SC termed incessant flow of illegal migrants into Assam as “aggression” and castigated the Centre for failing in its duty under Article 355 to protect the state. It said, “There can be no manner of doubt that Assam is facing ‘external aggression and internal disturbance’ on account of largescale illegal migration of Bangladeshis. It, therefore, becomes the duty of Union of India to take all measures for protection of Assam from such external aggression and internal disturbance as enjoined in Article 355.”

It quashed the ill-suited IMDT Act and directed effective identification of illegal migrants through tribunals under the Foreigners Act. Instead of implementing the directive, the Union and Assam governments attempted to obfuscate the issue by passing a new notification giving relief to illegal migrants from imminent identification. SC saw through the game and in December 5, 2006, pulled up both the governments [Sonowal-II, 2007 (1) SCC 174]. The problem of illegal migrants raised its ugly face yet again in Assam through recent riots. Other northeastern states have also been nervously watching similar demographic situations building up. It is time for the Centre and Assam, who are morally in contempt of the two SC rulings, to take concrete and decisive measures to solve the problem. Else, we will witness Assam-like flare-ups in more northeastern states.

2017: 90% of Assam natives don't have land-ownership papers

Prabin Kalita, May 2, 2017: The Times of India

A state-sponsored committee on protection of land rights of indigenous people, headed by former chief election commissioner Hari Shankar Brahma, has estimated that 90% of the natives of Assam do not possess permanent land `patta' (legal document for land ownership), while at least 8 lakh native families are landless.

According to an additional deputy commissioner of Nagaon district, about 70% of the land is owned by nonnatives there, which is perhaps the only district where non-indigenous people possess such a share of land, Brahma said.

The committee, formed in February as per CM Sarbananda Sonowal's instructions, is expected to submit its recommendations on how to protect the land rights of the indigenous people to the government in June.

“In all of Assam, 63 lakh bigha (1 bigha= 14,400 sq ft) of government land, including forest land, grazing ground and others, are under illegal occupation, while at least 7 to 8 lakh native families do not have an inch of land. Ninety per cent of the native people do not have myadi patta (permanent land settlement), they have either eksonia patta (annual land settlement) or are occupying government land,“ said Brahma.The committee also found that many natives of Tinsukia, Dibrugarh and Majuli districts, whose forefathers lost their land in the earthquake of 1950, own neither land nor documents. The committee has also been mandated to review the British-era Assam Land and Revenue Regulation Act, 1886 and suggest measures for its modification.

Sonowal, while deciding to set up the committee, had said the government was taking steps to formulate a new land policy because “without land there can be no existence of the Assamese race and it is the government's fundamental duty to protect the land of the original dwellers of the state and no compromise would be made in this regard“.

Hajela, IAS, Assam’s NRC coordinator maligned by both sides

September 1, 2019: The Times of India

Hajela still a villain, this time for 'small exclusion'

GUWAHATI: A year ago, IIT graduate-turned-bureaucrat Prateek Hajela (50) was portrayed as an asura (demon) being slain by goddess Durga at a rally in Bengali-majority Silchar for being the reason their citizenship was at stake. On Saturday, which marked the culmination of the six-year-long exercise to update the National Register of Citizens in Assam, Hajela still remained a villain - this time because of the "small" exclusion figure. Hajela, a 1995-batch IAS officer, is the state coordinator for Assam NRC exercise. He has been the BJP-led Assam government's bete noire ever since the Supreme Court rejected its plea for re-verification of documents submitted by the people in the districts bordering Bangladesh, after Hajela reported that he had already completed "incidental re-verification" of 27% of the applications.

The state government went to the extent of accusing Hajela - its own officer - as he belonged to the Assam-Meghalaya cadre, of keeping it in the dark about the NRC updation progress. Hajela has said little on these accusations though. His last interaction with the media was on July 30, 2018, when the final draft NRC was presented. Since then, he has kept himself away from the media following an SC stricture. Even the publication of the final NRC on Saturday was a low-key affair, with Hajela reaching out to the media with a statement released on official social media handles. Despite this, his name rang out in the streets of Guwahati as people defied prohibitory orders and protested against the final list. Born in Bhopal, Hajela was first posted in Assam as an assistant commissioner in Cachar district in 1996. In September 2013, he was appointed commissioner and secretary of the state home and political department by the then Congress government and also took over as the state coordinator of the NRC updation process as the nodal officer of the Registrar General of India. In a Facebook post in 2018, Hajela hinted at the difficult circumstances under which he was working. "In any endeavour where the intentions are pure and as are the ways and means, every obstruction is an opportunity.. ." What followed were waves of verbal attack on Hajela from BJP. On July 24, the state BJP said Hajela was working under the direction of "certain forces" to "publish a faulty NRC with names of illegal foreigners in it". On Saturday, all Hajela offered was a brief statement. "All decisions of inclusion and exclusion are taken by statutory officers. The entire process... has been meticulously carried out in an objective and transparent manner. Adequate opportunity of being heard has been given to all persons at every stage of the process," he said.

Status in 2019 Sept; background: 1985 onw

Nalin Mehta, Sep 10, 2019: The Times of India

As many as 19.07 lakh (almost 6% of the 3.29 crore who applied) were excluded from the final NRC list. Second, the rate of exclusions in the border districts with Bangladesh such as South Salmara (7.22%), Dhubri (8.26%) and Karimganj (7.57%) was much lower than districts like Karbi Anglong (14.31%) and Tinsukia (13.25%) where Assam’s bhumiputras have lived for centuries.

This is why Assam’s finance minister Himanta Biswa Sarma says the NRC is a “mixed bag” and that “we are in sorrow”. It is also why both the state and central governments went to the Supreme Court earlier this year for reverification of the NRC list. That request was rejected but the state government is appealing to the court to reconsider. The NRC is a legacy of the Assam Accord of 1985 and the Assam movement that preceded it. A key demand of that movement against ‘foreigners’ was for ‘detection, deletion and deportation’ of illegal Bangladeshi migrants. It was a demand that was specifically coded into the Assam Accord signed by the Rajiv Gandhi-led central government.

The last Assam government under Tarun Gogoi tried to start a project to update the 1951 NRC list with a pilot project in 2010 in Barpeta and Kamrup. It was put on the backburner after serious pushback. Things changed only after the Supreme Court mandated an updation exercise in 2013 after a writ petition filed by Assam Public Works. The exercise began in early 2015 and the court has been constantly monitoring the exercise since then. It has reportedly cost over Rs 1,220 crore, engaged 40,000 government employees, 8,200 contractual employees and took over five years.

What does it mean now? First, nobody is happy with the result. Law-abiding citizens have been seriously discomfited. The overall number of illegals identified is too low and the demographic spread of those who failed the NRC test is different from what political parties expected.

No one can defend exclusions like the case of Mohammad Sanaullah, who served the Indian Army for 30 years and the Assam border police before suddenly being declared an illegal. Or the case of 79-year-old Sunirmal Bagchi who was honoured in the state government’s Independence Day roll of honour before finding his name off the NRC. Or seven-year-old Somiara who has been facing “Bangladeshi” taunts because she was excluded from the NRC even though both her parents made it onto the list.

Second, though Congress could have made political capital, the state BJP has been ahead in seizing the political narrative so far. It positioned itself as an aggressive defender of locals against illegal outsiders. Now that the NRC is a mess, it is equally positioning itself as the defender of those who have been wrongly left out in the implementation. The state government made the district-wise NRC-exclusion numbers public in the state assembly on August 1, though the apex court got these earlier in a sealed cover. It is now arguing that 200 new foreigner tribunals being set up can be used to provide relief to those wrongly left out.

Centrally, home minister Amit Shah at the North Eastern Council meeting was guarded but specific in his first post NRC-publication comments: “Questions are being raised about the NRC by different sections but today I just want to say this that the BJP-led government is committed to ensure that not a single illegal immigrant enters the region.” The political messaging is unambiguous.

Third, in terms of protections for its Hindu base, BJP during the elections promised the Citizenship Amendment Bill, which envisaged citizenship to persecuted minority groups from Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Pakistan after six years of residence in India. It could conceivably be revived. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, during the Lok Sabha campaign, also promised scheduled tribe status to six communities: Tai Ahom, Matak, Moran, Chutia, Koch Rajbongshi and the tea tribes.

Fourth, it is difficult to oppose the principle of a citizenship register. The huge implementation problems in Assam, however, point to serious practical pitfalls. The big lesson is that India’s weak state apparatus did not prove robust enough for a strong state solution like this. BJP’s Delhi unit chief Manoj Tiwari recently demanded an NRC in the capital as well. It would be prudent to learn from the Assam example and not try it elsewhere in the country. We must fix the state’s backend first before such ambitious programmes.

Court judgements

Bangladeshis entering Assam after March 24, 1971 are illegal immigrants: SC, 2024

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Oct 18, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi : Supreme Court declared all Bangladeshi migrants who entered Assam on or after Mar 25, 1971, as illegal migrants. Given the grave adverse impact they have had on the state’s culture and demography, the Union and state govts must expedite their identification, detection and deportation, SC said.

A five-judge bench delivered this verdict by four to one majority while upholding the validity of Section 6A of Citizenship Act, which was introduced in Dec 1985 in sync with the 1985 Assam Accord that Rajiv Gandhi govt signed with students’ unions, which were agitating against massive illegal influx of Bangladeshis. The section’s validity was challenged in SC on the ground that it differed from the cut-off dates prescribed in Constitution for grant of citizenship.

National Register of Citizens

A history of the NRC issue

Kaushik Deka , Two men and a legal list “India Today” 15/2/2018

While the rest of the world welcomed 2018 on January 1, there were serpentine queues in Assam at multiple places from early morning. Anxious people waited to find their names in the first draft of the National Register of Citizenship (NRC) that was released by the state government as the clock struck midnight. This was the second time NRC has been published anywhere in the country-the first time was in 1951.

Political parties and social activists may have rushed to congratulate the people of Assam-19 million have found their names in the NRC while verification is going on for 13 million-but the credit for making the update of the NRC a reality goes to two citizen litigants: Pradeep Bhuyan, 85, and Abhijit Sarma, 43.

One of the significant clauses of the 1985 Assam Accord, signed between the Union government, the Assam government and leaders of the Assam agitation, was to update the 1951 NRC so that the state had an account of legal citizens. But the clause remained on paper and another tripartite agreement was signed in 2005 between the Centre, state government and leaders of the All Assam Students' Union. The new agreement decided to update the NRC and the state government started two NRC pilot projects in 2010 in two districts. The project, however, was aborted as members of a minority students' group resorted to violence.

In January 2009, Bhuyan, an alumnus of IIT Kharagpur, approached Sarma, an entrepreneur-turned-social activist, to file a PIL in the Supreme Court seeking deletion of 4.1 million 'illegal voters' from the voter list.

A case was registered in the apex court on July 20, 2009. The petitioners appealed to the court to monitor the process of updating the NRC instead of directing the government to do it. On April 2, 2013, the case reached the bench of Justice Ranjan Gogoi and H.L. Gokhale. Work on the NRC started in May 2015 and the court fixed December 31, 2017, as the date for the publication of the first draft of the NRC.

"Such work needs dedication, honesty and courage. That's why I approached Sarma," says Bhuyan, who avoids media attention. He wrote the draft of the first petition and used his own money to fight the legal battle. Bhuyan remained behind the scene and Sarma and his NGO, Assam Public Works (APW), founded by 36 businessmen in 2000, became the front of this crusade. "APW's first battle was against the ULFA. After 2008, we picked up the issue of illegal immigrants," says Sarma.

Sarma is aware that the battle is not over yet. The current update of the NRC has been done based on the Assam Accord that accepted 1971 as the cut-off year for anyone to be declared an illegal immigrant. In December 2012, Matiur Rahman, president of the Assam Sanmilita Mahasangha, filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court, demanding that the cut-off year be changed to 1951, a demand that has the support of the R.S.S. and Assam finance minister Himanta Biswa Sarma. The hearing on that case is likely to begin in April. If the court decides in favour of Rahman's petition, the NRC update process will become invalid.

What is the NRC?

5 Things To Know About Assam’s National Register Of Citizens, July 31, 2018: The Times of India

What is National Register of Citizens (NRC)?

During the Census of 1951, a national citizen register was created that contained the details of every person by village. The data included name, age, father’s/husband’s name, houses or holdings belonging to them, means of livelihood and so on. These registers covered every person enumerated during the Census of 1951 and were kept in the offices of deputy commissioners and sub-divisional officers as per the Centre’s instructions issued in 1951. In the early 1960sthese registers were transferred to the police.

Why was there a demand to update Assam’s NRC?

Since Independence till 1971, when Bangladesh was created, Assam witnessed large-scale migration from East Pakistan that became Bangladesh after the war. Soon after the war on March 19, 1972, a treaty for friendship, co-operation and peace was signed between India and Bangladesh. The migration of Bangladeshis into Assam continued. To bring this regular influx of immigrants to the notice of then prime minister, the All Assam Students Union submitted a memorandum to Indira Gandhi in 1980 seeking her “urgent attention” to the matter. Subsequently, Parliament enacted the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act, 1983. This Act, made applicable only to Assam, was expected to identify and deport illegal migrants in the state.

What spurred the Assam agitation? What was the outcome?

The people were not satisfied with the government’s measures and a massive statelevel student agitation started, spearheaded by All Assam Students Union (AASU) and the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP). This movement resulted in the ‘Assam Accord’ signed on August 15, 1985, between AASU, AAGSP and the central and state governments.

Who are included in the NRC?

Persons whose names appear in NRC 1951 or in any of the electoral rolls up to March 24, 1971, and their dependents are to be included in the current NRC. Persons who came to Assam on or after January 1, 1966, but before March 25, 1971, and registered themselves in keeping with the Centre’s rules for foreigners registration, and who have not been declared as illegal migrants or foreigners by the competent authority, could register. Foreigners who came to Assam on or after March 25, 1971, are to be thereafter detected and expelled as per the law. Apart from this, all Indian citizens including their children and descendants who moved to Assam post March 24, 1971, were eligible for inclusion in the updated NRC. But ‘satisfactory’ proof of residence in any part of the country (outside Assam) as on March 24, 1971, would have to be provided.

What happen to those whose name are not in the NRC 2018?

The July 30, 2018, NRC list is a draft and not the final one. People whose names are missing can still apply. The period to file such claims is from August 30 to September 28. Applicants can call toll-free numbers to enquire with their application receipt number.

The NRC explained

Chandrima Banerjee and Naresh Mitra, September 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee and Naresh Mitra, September 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee and Naresh Mitra, September 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: Chandrima Banerjee and Naresh Mitra, September 6, 2019: The Times of India

The National Register of Citizens (NRC) was released following a Supreme Court deadline of August 31 for its publication. NRC is a list of Assam's residents – prepared to identify bonafide residents and deport illegal migrants in the northeastern state bordering Bangladesh. About 19.07 lakh names were excluded from the final register, while names of 3.11 crore people were included.

Why August 31 deadline is important

In the run-up to the four-year-long SC-monitored exercise's culmination, anxiety levels were mounting. About 40.7 lakh names were excluded from the draft NRC released on July 31 last year. This increased to over 41 lakh names after an 'additional draft exclusion list' that dropped another one lakh names was published on June 26, 2019. Some 2.9 crore people out of a total 3.29 crore applicants were included in the NRC. For those who don't make it to the final list, a long and tough battle lies ahead where they will have to prove they are legal Indian citizens.

What gets you on the list?

To make it to the current list, names of family members of the applicant should be in the first NRC prepared in 1951 or in the electoral rolls up to March 24, 1971. Other documents include birth certificate, refugee registration certificate, land and tenancy records, citizenship certificate, permanent residential certificate, passport, LIC policy, government issued licence or certificate, bank/post office accounts, government employment certificate, educational certificate and court records.

The Assam Accord of 1985 formalised March 24, 1971 as the cut-off date to identify "foreigners" in the state as the Bangladesh Liberation War began the next day. But considering India's poor documentation culture, many genuine citizens have been unable to furnish the required documents.

What happens if you are excluded?

The Union home ministry has clarified that "non-inclusion of a person's name in the NRC does not by itself amount to him/her being declared a foreigner" as the person will be allowed to present his/her case before designated foreigners' tribunals. The state government has also said that those left out of the NRC will not be detained "under any circumstances" until the foreigners' tribunals declare them foreigners.

Foreigners’ tribunals, promised under the Assam Accord, are quasi-judicial bodies that exclusively adjudicate matters of citizenship. Those who have been declared foreigners by tribunals are not eligible for inclusion in the NRC. In case a person is included in the NRC but declared a non-national by a tribunal later, it is the tribunal’s verdict that will prevail.

According to Assam chief minister Sarbananda Sonowal, the Centre may consider bringing in legislation to set right wrongful inclusions (of foreigners) and exclusions (of genuine citizens) on the list. However, this measure, if warranted, will take place only after the NRC is published.

Adequate arrangements will be made by the state govt to provide full opportunity to appeal against non-inclusion. Every individual, whose name does not figure in the final NRC, can represent his/her case in front of the appellate authority, i.e. Foreigners Tribunals. Thus, non-inclusion of a person’s name in the NRC does not by itself amount to him/her being declared as a foreigner

Where to appeal?

Appeals can be made under Section 8 of Schedule to the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003. The time limit to file an appeal has been increased from 60 days to 120 days – till December 31, 2019. A total of 1,000 tribunals have been sanctioned by the home ministry. If one loses the case in the tribunal, the person can move the high court and, then, the Supreme Court. No one will be put in detention centres until all legal options are exhausted, the government has stated.

The Assam government has said it will provide free legal aid to 'needy' people whose name does not figure on the list. The state's ruling BJP and opposition Congress also plan to 'assist' bonafide citizens who are kept out of the NRC. NGOs too have volunteered to navigate the complex issue of Indian citizenship after August 31.

What happens if you are declared a foreigner?

The state is setting up detention centres exclusively for those declared foreigners after exhausting all legal routes. Repatriation of such people looks difficult as India and Bangladesh do not have any treaty in this regard. The border police personnel who didn’t make the cut

Mohammad Sanaullah, 52, joined the Indian Army in 1987. In his 30-year-long career, he served in J&K at the height of insurgency in the 90s. After retiring from the Army as an honorary lieutenant in 2017, he joined the border wing of Assam Police. The border wing is responsible for detecting “foreigners” in the state.

On May 23, the former Army man found himself on the other side of the opaque process – he was tagged a “non-national”. The Foreigners’ Tribunal at Boko in Kamrup district declared him a foreigner on the grounds that he had “miserably failed to prove” his citizenship. He was summarily dismissed from the Assam Police. He was dropped from the NRC and, subsequently, sent to a detention centre in Goalpara. Those declared foreigners by tribunals cannot be included in the NRC, at least until they are cleared as citizens by a tribunal.

Sanaullah is out on bail now, but his chances of making it to the final NRC appear slim.

The history

First created in 1951, NRC is a list of Indian citizens in Assam. At the time, two other states in the northeast – Manipur and Tripura – were also given grants by the Centre to create their own NRCs, but it never materialised. Assam is presently the only state in India to have an NRC. The grounds then were the same as those now – “unabated” migration from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). A year before the first NRC was released, the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act, 1950 was passed by the Centre, allowing the government to deport anyone whose stay was “detrimental to the interests” of the people. An exception was made only for those displaced by “civil disturbances” in what was then East Pakistan. The Act was repealed in 1957.

Assam artist in I-Day roll of honour, out of draft NRC

79-year-old Sunirmal Bagchi, a well-known cultural activist, made it to the Assam's govt's Independence Day roll of honour, making him eligible for monthly pension for his contributions in the field of culture, but he hasn't found a place in the draft NRC.

Born in Assam on September 21, 1943, Bagchi even has a birth certificate issued by the Silchar municipal board. He thus fails to understand how he's been categorised as a 'foreigner'. Having cleared the citizenship test earlier, he was included in the draft NRC published last year. But for some reason his name was later dropped and he was asked to reappear at an NRC centre with the relevant documents. He's now waiting to see if his name will be included in the final version.

How first NRC of 1951 was compiled

The first NRC was essentially another form of the 1951 Census report, which was prepared on the basis of questions asked by enumerators. It listed each house and property holding along with the names of those staying in or owning them. The list comprised of those who lived in India on January 26, 1950, or were born in India or had parents who were born in India or had been living in India for at least five years before the January 26, 1950 cut-off. Till 1960, these records were maintained by every deputy commissioner and sub-divisional officer, following which, they were turned over to the police, who used them to identify “Pakistani nationals” under the Prevention of Infiltration from Pakistan scheme.

Why the NRC update in Assam

When the NRC was first created, the idea was that it would be updated from time to time, just like the Census. But, that never happened. The NRC is basically an outcome of the All Assam Students’ Union's (Aasu) demand for removing the names of all illegal migrants from electoral rolls after a “rise” in the number of Bengali voters in Mangaldoi district in 1979 was noticed. The Mangaldoi episode led to a six-year-long anti-foreigner movement in Assam, culminating in the signing of the Assam Accord in 1985. Aasu and the Asom Gana Sangram Parishad (present-day Asom Gana Parishad) were the two main protagonists of the agitation. The accord, signed between the Centre, the Assam government and the agitators agreed to identify and deport all “foreigners” living in Assam. It identified March 24, 1971 as the cut-off date for identifying illegal migrants.

As the problem of infiltration from across the border persisted, in 2005, the signatories of the Assam Accord agreed to update the 1951 register to detect illegal non-nationals and settlers. Owing to a lack of consensus on modalities, the government took another five years to initiate a pilot project for NRC update, which was abruptly called off because of violent protests by students from the minority community. In 2013, the Supreme Court, in response to a series of writ petitions, ordered the Centre and the Assam government to resume the NRC update process. But, it was only after a wait of two years that the process finally started in 2015.

How the NRC was updated

The 1951 NRC was prepared on the basis of door-to door enumeration. The present process requires people to apply for inclusion in the updated NRC. Applications were accepted till August 31, 2015. The first draft was published at midnight on December 31, 2017, followed by a final draft on July 30, 2018. Those who did not make it to this draft were allowed to re-apply from August 30 to September 38, 2018. About 36 lakh people have re-applied for inclusion at various NRC seva kendras.

What the NRC is not

The NRC is not a proof of citizenship. The original NRC was considered an administrative document, not a public one. However, during the current NRC update process, applicants obtained their legacy data from the 1951 NRC that was made available in the public domain, both online and offline.

Possibility of NRC in the rest of India The Centre has been pushing for NRCs in every state. Nagaland has already started an exercise to create a similar database of citizens known as the Register of Indigenous Inhabitants. The Centre has also announced plans for a National Population Register (NPR) which will contain demographic and biometric details of citizens. A pilot NPR project was launched when the UPA government was in power but was not completed.

A snake-and-ladder case for Sahitya Akademi winner

Durga Khatiwada, 60, (second from left) is president of the Asom Nepali Sahitya Sabha. In 2001, he won the Sahitya Akademi Award. He had made it to the draft NRC, published in July 2018. This year, on June 26, he discovered he was among the one lakh people dropped from the draft NRC after being included. The reason? He had been tagged as a ‘doubtful’ voter by the Election Commission earlier. He was cleared of the tag in 2015, but that did not help.

Gorkhas came to the northeast as early as the 19th century when they were recruited by the British in the Assam Light Infantry. The recruitment followed the 1815 Treaty of Segowlee signed between the East India Company and Nepal after the Anglo-Gorkha War.

Last year, a Union home ministry notification had ruled that any member of the Gorkha community who was an Indian citizen in 1950, or an Indian citizen by birth, naturalization and registration are not “foreigners” and will not be referred to foreigners’ tribunals. The rule appears to have made no difference to the fate of Khatiwada and more than 25 lakh Gorkhas like him, who await the August 31 NRC.

From Assam Accord to NRC: A timeline

1951

First Census of Independent India conducted. First NRC compiled based on Census

Dec 30, 1955

Citizenship Act comes into force – set rules for Indian citizenship by birth, descent, registration

1971

Bangladesh war leads to influx of refugees in India

1978

Voters' list in 1978 bypoll to Mangaldoi Lok Sabha seat sees surge. All Assam Students Unions (Aasu) wants elections called off till names of 'foreigners' struck off electoral rolls

1979-1985

Six-year Assam Agitation led by Aasu and All Asom Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) calls attention to problem of 'illegal immigration’

Feb 18, 1983

2,191 people, mainly Muslims, in central Assam killed, allegedly by Assamese tribals. Nellie Massacre takes place amid protests by indigenous Assamese against decision to grant millions of immigrants the right to vote in state elections, that ultimately saw voter turnout of just 32%

Dec 12, 1983

Parliament passes Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act 1983 to stem inflow of immigrants. Act struck down by SC in 2005

Aug 15, 1985

Assam Accord signed by Centre, Assam govt, Aasu and AAGSP to end agitation and provide for 'detection, deletion and deportation' of foreigners as defined by 1983 Act

2003

Citizenship (Amendment) Act introduced

July 2005

SC strikes down Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act, 1983, calling it unconstitutional

2013

SC calls for update of NRC; process begins in 2015

Dec 31, 2017

First draft of new NRC published. Only 1.9 crore names out of 3.29 crore applications included

July 30, 2018

Final draft of NRC with 2.89 crore names published. 40 lakh names omitted. Exclusions increased to over 41 lakh in June 2019

December 2017/ Assam recognizes 1.9cr of 3.29cr citizens as legal

Assam publishes first draft of NRC with 1.9 crore names, January 1, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

First draft of the National Register of Citizens was today published with the names of 1.9 crore people

The rest of the names are under various stages of verification, and the entire process will be completed within 2018

People can check their names in the first draft at NRC sewa kendras across Assam

The much-awaited first draft of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was published with the names of 1.9 crore people out of the 3.29 crore total applicants in Assam recognizing them as legal citizens of India. The rest of the names are under various stages of verification, Registrar General of India Sailesh said at a press conference held at midnight where he made the draft public.

"This is a part draft. It contains 1.9 crore persons+ , who have been verified till now. The rest of the names are under various stages of verification. As soon as the verification is done, we will come out with another draft," he said.

NRC State Coordinator Prateek Hajela said those people whose names have been excluded in the first list need not worry.

"It is a tedious process to verify the names. So there is a possibility that some names within a single family may not be there in the first draft," said Hajela.

"There is no need to panic as rest of the documents are under verification," he said.

Asked about the possible timeframe for the next draft, the RGI said it will be decided as per the guidelines of the Supreme Court, under whose monitoring the document is being prepared -- in its next hearing in April.

The entire process will be completed within 2018, Sailesh said.

The application process started in May, 2015 and a total of 6.5 crore documents were received from 68.27 lakh families across Assam.

"The process of accepting complaints will start once the final draft is published as rest of the names are likely to appear in that," Hajela said.

People can check their names in the first draft at NRC sewa kendras across Assam from 8am. They can also check for information online and through SMS services.

The RGI informed that the ground work for this mammoth exercise began in December 2013 and 40 hearings have taken place in the Supreme Court over the last three years.

Assam, which faced influx from Bangladesh since the early 20th century, is the only state having an NRC, first prepared in 1951. The Supreme Court, which is monitoring the entire process, had ordered that the first draft of the NRC be published by December 31 after completing the scrutiny of over two crore claims along with that of around 38 lakh people whose documents were suspect.

The National Register of Citizens, 1951-2017

From Naresh Mitra, January 2, 2018 The Times of India

See graphic:

Beginning 1951, a brief history of the National Register of Citizenship

40% names not included in first draft

The first draft of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), released at midnight on Sunday, had several surprises, with rebel leader Paresh Baruah finding a place and senior political leaders, including Lok Sabha MP and All India United Democratic Front chief

Badruddin Ajmal, failing to make it to the draft.

Altogether, 1.9 crore names out of 3.3 crore applicants were included in the first draft. Registrar General of India Sailesh said the verification process of the remaining 1.4 crore applicants (40%) was still on.

Chief minister Sarbananda Sonowal had said on Sunday that not a single genuine Indian citizen would be excluded from the final NRC.

Ulfa (Independent) commander-in-chief Paresh Baruah, who has been seeking secession of Assam from India, is believed to be holed up somewhere along the China-Myanmar border.

The names of five of his family members also appear. “Our entire family is happy. I had submitted the application at the NRC seva kendra myself. So we were certain his name would feature in the list. He may not be aware of his inclusion,” Baruah’s sister-in-law Renu said on Monday.

Badruddin Ajmal missing from list

The names of Baruah’s wife, Boby Bhuyan Baruah, and his two sons Ankur and Akash, do not figure in the list, though. “We could not getthe namesofhis wife and children included because some documents were missing. We will complete the process in the next phase,” Renu said.

Baruah’s brother Bikul, a teacher, said the rebel leader had left home 37 years ago. “I was 12 when he left home. We are elated his name is there along with all family members. He is a son of the soil. He has taken birthin this village. So there is no question of his name not appearing,” he said.

However, many leaders from across the political spectrum don’t figure in the first list. Prominent among them is Ajmal, who represents Muslim-majority Dhubri, bordering Bangladesh, in western Assam. Besides Ajmal, the names of his brother Sirajuddin, also a Lok Sabha MP, and two sons are missing. “Their documents are being verified,” AIUDF general secretary Aminul Islam said. AIUDFMLAHafizBashir Ahmed Quasimi and his family have also notbeen includedin the draft NRC, Islam added.

BJP MLA from Hojai Shiladitya Dev who had in November triggered a controversy when hesaid mostMuslims in the state are from Bangladesh, said his name was missing from thedraftbut thoseof his family members were included. “I am not concerned... I can understand the tremendous pressure under which those involved in the process were working,” hesaid.

CongressMLANurulHuda alsowoke up tofind his name missing. “Like me, 70% of the residents of Rupohihat (which he represents) are yet to be included,” he said.

2018, July: 40 lakh people declared non- Indian

From: Prabin Kalita, 40L in Assam labelled ‘illegals’ in massive SC-monitored drive, July 31, 2018: The Times of India

After a massive Supreme Court-monitored exercise to identify illegal migrants living in Assam, the Registrar General of India (RGI) adjudged that 40 lakh people in the state are not Indians, and hence, ineligible to be included in the draft National Register of Citizens (NRC). The finding sparked off a political confrontation between BJP and its opponents, and could also trigger ethnic and communal tensions.

Altogether, 3.29 crore residents of Assam had applied for their inclusion in the NRC, which the RGI had begun to update in 2010 to detect and deport illegal migrants—mainly from Bangladesh. Only 2.89 crore have made the draft NRC. The RGI has given one more chance to those who couldn’t make it to the NRC to prove their citizenship. They will have to file claims between August 30 and September 28. The fundamental rights and privileges they enjoy as Indians will remain unchanged till the NRC update on December 31. The RGI said the EC would decide on voting rights.

Govt tries to reassure those not in NRC

RGI Sailesh said, “This is a draft, we’ll wait for the final one.” On the voting rights of these 40 lakh people, he said, “This is a subject matter of the Election Commission and I am not the competent authority to comment on it.”

The RGI added, “There could be several reasons why these people could not substantiate their claims.”

Speaking on similar lines, MHA joint secretary (northeast) Satyendra Garg added, “No punitive action will be taken against them. We will wait for final NRC.”

Of the 40 lakh people who did not make it to the NRC, 2.48 lakh had already been marked as doubtful or ‘D’ voters by the Election Commission. About 1.5 lakh names, which could not be included the first part draft published in December 2018, have been deleted.

The exercise to update the NRC stems from the Assam agreement that the Centre signed in August 1985 with All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) who had launched a huge agitation against the influx of illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, saying that the “demographic invasion” threatened to reduce the Assamese to a minority in the state and obliterate their culture.

While the Centre agreed that those who were found to have illegally entered Assam after March 1971 will be detected, disenfranchised and deported, the verification of citizenship claims of residents of the state happened lethargically and in fits and starts until 2010, when it was stopped due to violence and other reasons. The SC ordered its resumption in 2013, but the RGI could begin the exercise only in 2015.

Controversies and allegations that had led to the NRC update being put on the hold returned as soon as the RGI announced its findings on Monday. Congress president Rahul Gandhi; West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee, CPM and RJD attacked the results, blaming it on BJP’s communal politics.

Home minister Rajnath Singh and Assam CM Sarbananda Sonowal stood by the outcome of the massive exercise, while underlining that it was undertaken at SC’s instance. Assam deputy CM Himanta Biswa Sarma argued that elimination from NRC of those who were not Indian nationals will fend off a huge danger facing the Assamese.

SC allows use of 5 contentious documents

In a big relief to 40 lakh people excluded from the final draft of Assam’s National Register of Citizens, the Supreme Court lifted the stay on use of five contentious documents for seeking inclusion in the NRC and extended the deadline for filing claims and objections from November 25 to December 15.

A bench of Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justice Rohinton F Nariman had suspended use of the five documents — NRC 1951, citizenship certificate, electoral roll (both Assam and Tripura), refugee certificate and ration card, all issued before March 24, 1971 — in applications filed for claiming inclusion in the NRC. With this, people seeking inclusion of their names in the NRC can now rely on all 15 documents stipulated in the original standard operating procedure.

The court had suspended use of the five documents as NRC state coordinator Prateek Hajela had informed the judges that during preparation of the draft NRC, it was found that most rejected claims were based on forged documents belonging to these five categories. Hajela was of the opinion that “it is better to leave out a genuine citizen than include a noncitizen in the NRC”.

Justices Gogoi and Nariman said it was a wrong approach on the part of Hajela as no genuine citizen could be kept out of the NRC merely because of apprehension that these five documents could have been forged and submitted with the claim documents. However, the court took note of the apprehension and told Hajela that he could subject any claim application based on these five documents to additional layers of scrutiny.

“Needless to say, all such documents must be subjected to a thorough process of verification and would be accepted only after due and complete satisfaction of the genuineness of the same,” it said. The SC said time for issuing notice after digitisation and completion of all formalities and requirements on received claims and objections applications would be January 15 and the verification process for these applications would start from February 1.

Interestingly, a small population of Gorkhas in Assam, through senior advocate Narender Hooda, complained that members of the community, despite living in the state for generations, were being excluded from the NRC. CJI Gogoi asked Hajela, “Do you have any problem with Gorkhas? They are an asset to the nation. Do include them in the NRC.”

The bench said the schedule for other issues relating to finalisation of Assam NRC would be given after Hajela files a report before the court on expiry of the December 15 deadline for submitting applications for inclusion and exclusion of names in the NRC.

2019: More than 19 lakh excluded from NRC final list

Naresh Mitra, August 31, 2019: The Times of India

From: Prabin Kalita, September 1, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic :

2019: The highlights of the final NRC list

Final Assam NRC list out: Over 3.11 crore included, more than 19.06 lakh excluded

GUWAHATI: The much-awaited updated Final National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam was released on Saturday, excluding names of 19.07 lakh applicants + , including those who did not submit claims. Names of 3.11 crore applicants were included in the final NRC, the NRC State Coordinator's office said.

A total of 3,30,27,661 persons applied for NRC through 68,37,660 applications.

As soon as the final list of the National Register of Citizens in Assam was published, people in large number rushed to the NRC Seva Kendra in Barpeta district on Saturday to check their names. The people were seen standing in serpentine queues to check their names on the final NRC list at the Center.

"All the names of my family members are there in the list except my daughter-in-law. Though we had submitted all the documents to the authorities. We do not have any idea how this has happened. Will go through the process again," a local named Motiurrahman said.

The final list was published at 10 am and the hard copies of the Supplementary List of Inclusions are available for public viewing at the NRC Seva Kendras (NSK), offices of the deputy commissioner and offices of the Circle Officer during office hours, the statement said. The status of both inclusion and exclusion of the people from the list can be viewed online on the NRC website, www.nrcassam.nic.in.

The process of NRC update started in Assam as per order of the Supreme Court in 2013 under the monitoring of the apex court. The process of receipt of NRC application started during the end of May 2015 and ended on August 31, 2015.

"The exercise of NRC update is a mammoth exercise involving around 52,000 state government officials working for a prolonged period. All decisions of inclusion and exclusion are taken by these statutory officers. The entire process of NRC update has been meticulously carried out in an objective and transparent manner. Adequate opportunity of being heard has been given to all persons at every stage of the process. The entire process is conducted as per statutory provisions and due procedure followed at every stage," NRC coordinator Prateek Hajela said in a statement.

Any person who is not satisfied with the outcome can file appeal before the Foreigners Tribunals within 120 days. Assam government has earlier said those left out of the NRC will not be detained under any circumstances until the Foreigners Tribunals declare them as foreigners.

The complete draft NRC was published on July 30, 2018, wherein 2,89,83,677 numbers of persons were found eligible for inclusion. Thereafter, claims were received from 36,26,630 numbers of persons against exclusions. Verification was also carried out of persons included in draft NRC.

Objections were received against inclusion of 1,87,633 persons whose names had appeared in complete draft.

On June 26 this year, another Additional Draft Exclusions List was published on where 1,02,462 persons were excluded.

Assam, which has faced an influx of people from Bangladesh since the early 20th century, is the only state having an NRC which was first prepared in 1951.

(With inputs from agencies)

The religious demographics of Assam

2011 census

The Times of India, Aug 26, 2015

See graphic

Bharti Jain

Muslim majority districts in Assam up

Assam, where illegal immigration from Bangladesh has been a concern, continues to show demographic changes with the 2011 Census finding nine of its 27 districts to be Muslim-majority . Adding to six such districts listed in 2001 Census, the 2011 Census has shown Bongaigaon, Morigaon and Darrang to be Muslim-majority. In 2001 Census, the districts in Assam with a larger Muslim population as compared to Hindus, were Barpeta, Dhubri, Karimganj, Goalpara, Hailakandi and Nagaon. Bongaigaon then had 38.5% Muslim population, Morigaon 47.6% and Darrang 35.5%.

As per 2011 Census, Dhubri has 15.5 lakh Muslims compared to 3.88 lakh Hindus, Goalpara has 5.8 lakh Muslims and 3.48 lakh Hindus, Nagaon 15.6 lakh Muslims and 12.2 lakh Hindus, Barpeta 11.98 lakh Muslims and 4.92 lakh Hindus, Morigaon 5.03 lakh Muslims and 4.51 lakh Hindus, Karimganj 6.9 lakh Muslims and 5.3 lakh Hindus, Hailakandi 3.97 lakh Muslims and 2.5 lakh Hindus, Bongaigaon 3.71 lakh Muslims and 3.59 lakh Hindus and Darrang 5.97 lakh Muslims and 3.27 lakh Hindus. Other districts with a significant share of Muslims are Cachar (6.5 lakh against 10.3 lakh Hindus), Kamrup (6.01 lakh Muslims against 8.77 Hindus) and Nalbari (2.77 lakh Muslims against 4.91 lakh Hindus).

In 1998, then governor of Assam S K Sinha had, in a report on illegal influx of Bangladeshi immigrants into Assam, warned that the “silent demographic invasion of Assam may result in the loss of the geostrategically vital districts of Lower Assam“.

Minority community, district-wise

From: Prabin Kalita, March 31, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

Hindus in minority in Assam districts, 2011

Barak Valley

Publication of the final draft of the NRC brought some relief to Barak Valley, which registered the lowest rate of inclusion in the first draft when the names of only 24 lakh people out of total 41 lakh were included.

However, in the final draft, the number went up to 37 lakh. In its three districts, the rate of exclusion is the lowest in Hailakandi (8%), followed by Karimganj (8.47%) and Cachar (12.58%). “There was a time when the Barak Valley was equated with Bangladesh,” said Unconditional Citizenship Demand Forum convener Kamal Chakraborty. “The final NRC draft should put such assumptions to rest,” he added. “For long, the Barak Valley has been thought to be sheltering Bangladeshi immigrants. But the truth has now been revealed,” Barak Valley-based historian Sanjib Deb Laskar said.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016

Speaker protests against Citizenship Bill, BJP red-faced

Prabin Kalita, January 10, 2019: The Times of India

In an embarrassment to BJP, Assam assembly speaker Hitendra Nath Goswami on Wednesday said the decision to pass the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 in the Lok Sabha was an act “in haste” which was done without “taking the indigenous people of Assam into confidence”. He urged the Centre to ensure protection of the state’s indigenous people on the basis of the 1985 Assam Accord.

Goswami, a former Asom Gana Parishad minister who joined BJP in 2016, said in a statement, “The waves of incidents centred around the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill 2016 here in (the) past few days have touched me personally.”

The legislator from Jorhat said: “While holding a constitutional post, along with my personal hopes, it is my duty to show respect to my country’s democratic system.”

Goswami said a Speaker need not opine on the enactment of a law. However, he added, “I think that the central and state governments would give respect to the views and

opinions expressed by the people of Assam and adopt immediate and appropriate measures to resolve the present unrest in the state which has been created after Lok Sabha passed the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill in haste without taking the people of Assam into confidence.”

The Speaker further said that his “conscience does not allow (him) to support any action, which the indigenous people of Assam do not want to accept because it could destroy the unity and harmony among the people”.

Goswami’s is the second voice of dissent from within BJP against the amendment to the Citizenship Act, 1955. On Tuesday, soon after the Lok Sabha passed the bill, former Assam BJP spokesperson Mehdi Alam Bora resigned from the party. In Meghalaya, BJP’s minister in the Conrad Sangma cabinet, AL Hek, said he too supported the state government’s resolution against the Bill.

Meanwhile, two days after the AGP walked out of its alliance with BJP in the Assam government, another ally, Bodoland People’s Front protested against the Bill.

Zubeen starts own stir

Pranjal Baruah, Bill protesters form a 10-km human chain, January 18, 2019: The Times of India

From: Naresh Mitra, January 18, 2019: The Times of India

Zubeen Garg, thesinger who sang the official song of BJP’s 2016 poll campaign in Assam, has expressed regret over his association with the party.

Launching his own protest campaign against the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 at Tezpur in Sonitpur district on Thursday, coinciding with ‘Shilpi Divas’, a day observed annually to pay homage to noted Assamese playwright Jyoti Prasad Agarwala, Zubeen said, “I don’t support any political party. I sang for BJP thinking the Sarbananda Sonowalled government would respect and do the needful for the state’s people. But if this government plays foul then I am going to stand against them too.” Several fans, locals and students gathered at the venue to listen to Zubeen on Thursday.

In Jorhat’s Selenghat area, locals formed a 10-km human chain to mark their protest. Protests and road blockades were reported

The anti-CAA agitation

2019: The Gamosa becomes the “face” of protests