Babhan

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

Contents |

Babhan

Tradition of origin

What are the Badhans Bhuinhar Zamindar Brahman, Girhasth Bmhman, Pachhima Bmhman, Magaha.llii Brahman, Ajagyak Bmhman, Zaminddr, chaudhrjji, a large and influential caste which counts among its members some of the chief l.andholders of Behar. Regarding the origin of the Babhans, a variety of traditions are current. One story represents them as the descendants of the Brahman rulers whom Parasu Ram set up in the place of the Kshahiyas slain by him, and who in course of time abandoned their Brahmanical duties and took to the profession of landholding. Another tells how a certain king of Ayodhya, being childless, sought to remove his reproaoh by the sacrifice of a Brahman and bought for this purpose the second son of the Rishi J amadagni, the father of Parasu Ram. By the interven¬tion of Viswamitra, the maternal uncle of the victim, the Raja was enabled to get a child without bloodshed; but the young Brahman was held to have been degraded by the sale, and was called upon to settle down on the land and become the forefather of the Bibhan caste.1 A third legend, perhaps the best known of all, traces the 13abhans back to a sacrifice offered by Jarasandha, King of Magarlha, at which a very large number of Brahmans, some say a lakh and a quarter, were required to be present.

Janisandha's Dewan, a Kayasth of the Amasht or Karan sub-caste, did his best to meet the demand, but was driven to eke out the looal supply by distributing sacred threads among members of the lower castes and palming them off on the king as genuine Brahmans. J arasandha's suspicions being roused by the odd appearance of some of the guests, the Dewan was compelled to guarantee their respectability by eating the food which they had cooked; while the Brahmans thus manufactured, failing to gain admission into their supposed caste, had to set up a caste of their own, the name of which (Babhan or Ballman) is popu¬larly supposed to mean a sham Brahman; "just as in some districts an inferior Rajput is called a Raut, the corruption of the name betokening the corruption of the caste."

Not promoted Non-Aryans

The last theory is at onoe refuted by the appearance and demeanour of the caste. "They are," says Not promoted Non• Mr. Beames, "a fine manly race, with the deli-Aryans. cate Aryan type of feature in full perfection."

1 'l'he legend roferred to is that of sunah sephns, told in the Aitarey" Bmf!mana and in a . lightly different form in the Ramayana. This type, I may add, is singularly uniform and persistent among the Babhans, which would not be the case if they were descended from a crowd of low-caste men promoted by the exigencies of a particular occasion; for brevet rank thus acquired would in no case carry with it the right of intermarriage with pure Brahmans or Rajputs, and the artificially-formed group, being compelled to marry within its own limits, would necessarily perpetuate the low-caste type of features and complexion. As a matter of fact, this is what happens with the sham Rajputs whom we find in most of the outlying districts of Bengal. They marry among themselves, never among the true Rajputs, and their features reproduce those of the parti¬cular aboriginal tribe from which they may happen to have sprung.

If, then, the hypothesis of a low-caste origin bren.ks down, there remains the question-Are the Babhans Brahmans who have somehow been degraded and dropped out of the ranks of their original caste? There seems to be no p?'ima facie improbability in this theory. Within the Brahman caste itself we find plenty of instances of inferior sub¬castes being formed owing to the adoption of practices deemed inconsistent with the dignity of a Brahman. The Agradani, Acharji, and Varna Brahmans are cases in point. There is no reason there¬fore in the nature of the caste system why the Bftbhans should not be Brahmans who, having lost status for some reason now forgotten, broke off entirely from the parent caste instead of accepting the position of an inferior sub-caste. The suggestion that they were degraded by taking to agriculture mnst of course be put aside, for, as Mr. Beames has pointed out, "there are many thousands of Brahmans in the same part of the country who are engaged in agricultural pursuits, but without losing caste, such as 'fiwaris, Upadhyas, OjMs or Jbas, and others."

Nor degraded Brahmans

An examination of the sections or exogamous groups into which the Babhans are divided appears, however, to -tell strongly against the hypothesis that they are degraded Brahmans. These groups are usually the oldest and most durable element in the internal organi¬zation of a caste or tribe, and may therefore be expected to offer the clearest illdications as to its origin. Now we find among the Babhans section-names of two distinct types,-the one territorial, referring either to some very early settlement of the section, or to the birthplace of its founder, and the other eponymous, the eponym being in most cases a Vedic rishi or inspired saint. The names of the former class correspond to or closely resemble those current among Rajputs; the names of the latter are those of the standard Brahman¬ical gotras. Lists of both are given in Appendix I, S.v. 2I!1ablnm. "Where the matrimonial prohibitions based on these two classes of sections conflict, as must obviously often happen where every member of the caste necessarily belongs to both sets, the authority of the territorial class ' overrides that of the eponymous or Brahmanical class. Suppose, for instance, that a man of the Karanch territorial section and of the Sanclilya eponymous section wishes to marry a woman of the Sakru:witr territorial section, the fact that she also belongs to the Sandilya eponymous section will not operate as a bar to the marriage. Whatever may be the theory of the purohits of the caste, the Brahmanical gotm is disregarded in practice, and doubtful cases are decided in accordance with the mltl or territorial section to which the parties belong. This circumstance seems to indicate that the telTitorial sections are the older of the two, and are probably the original sections of the caste; while the eponymous sections have been borrowed from the Brahmans in comparatively recent times.

It would follow that the Babhans are an offshoot, not from the Brahmans, but from the Rajputs. If Babhans had originally been Brahmans, they would at the time of their separation from the parent caste have been already fitted up with a complete set of Brah¬manical gotras, and it is difficult to imagine any reason which could have induced them to borrow a strange and much more elaborate set of sections from a tribe of inferior status, and to relegate their own sections to an entirely subordinate position. Territorial sections, moreover, do not lend themselves to the process of borrowing.

They are as a rule exceedingly numerous; the meanings of their names are obscure and difficult to trace; and, with the exception of a few names borne by famous Rajput clans, they are wanting in the note of social distinction. The Brahmanical gotras, on the other hand, form a clearly¬defined and not inconveniently-numerous group to which well-known and honourable traditions attach; they can be borrowed en masse with¬out any particular trouble; and the influence of Brahman pltro/tits is sufficient to diffuse them throughout any caste which affects a high standard of ceremonial purity and wishes to rise in the social scale. Numerous examples of the process of borrowing the Brahmanical eponymous gotras can be found among most of the lower castes at the

present day : I know of no instance of a caste adopting sections of another type. rI'o take a familiar illustration: it is as unlikely that a rising caste would borrow territorial sections when the Brahmanical gob•as were to be had for the asking, as it is that an English manu¬facturer who has got on in the world and is about to change his name would select Billing, Wace, or one of the earlier English patronymics instead of some more high-sounding name which may have come in with the Conquest. Kasyapa, Sandilya, and the other Bra1manical section names do for the rising castes of Bengal what Vavasour, Bracy, and Montresor are supposed to do for the wAalthy parventt in England.

It should be added here that alongside of the clearly territorial section names we find a few names of another type, such as Baghauchhia, BeJauria, Kastuar, which are said to have reference to the tiger, the bet tree (cegle mannelos), and the lias grass, and Harariu, Kodaria, Bhusbarat, Domkatar (foundling, spade-wielder,husk-picker, Dom's knife),. which seem to be nicknames of the same kind as we meet among some of the Himalayan tribes. In the absence of evidence that the members of the first three sections regard with veneration the animal and plants whose names they bear, we are hardly justified in pronouncing the names to be survivals from the totemistic stage. Some suggestion of inferiority does, however, seem to attach to the last foUl' sections, a,nd this point is more fully discussed below. For the purpose of controlling connubial arrangements, both of these classes seem to possess the same value as the territorial section, so that the argument stated above is not affected.

Probably a branch of the Rajputs

The considerations set forth above appear to me to render it highl probable that the Babhans are a branoh . It must, however, be admitted That evidence in favour of a Brahmns origin is not wanting. Mr. Sherring lays stress on the faot that the Bhuinhars of Benares "oall themselves Brahmans; have the got."as, titles, and family names of Brahmans, and praotise for the most part the usages of Brahmans." In Behar, though the claim to be Brahmans is not invariably put forward, Brah¬manical titles, such as Misr, Pame, and Tewari, are used along with the Rajput titles of Singh, Hai, and Thakur. In Shahabad and in parts of the N orth-Western Provinces members of other castes accord to a Babhan the salutation pmnam ordinarily reserved for Brahmans j while the Babhan responds with the benediotion asirbad. Further south, however, this practioe is unknown j and in Patna a Babhan would give the first greeting to a Kayasth, thereby implioitly reoognising the superior status of that caste in the sooial system.

Marriage exogamy

Like the Rajputs, the BabMarriage exohans exclude the seotion of both father and mother, or, in other words, forbid a man to marry a woman who belongs to the same section as he himself or his mother. The operation of this rule is further extended by the manner in which it is applied. Aooount is taken, not merely of the section to whioh the proposed bride herself belongs (i.e., her father's seotion), but also of her mother's seotion; so that the marriage will be barred if the bride's mother belonged to the same section as the bridegroom's mother, though of oourse neither bride nor bridegroom oan be members of that seotion. In respect of prohibited degrees, they follow the rules current among the Kayasths and explained in the article on that caste.

Endogamy

Among the Babhans of Behar, as among the Rajputs, no endog¬d amous divisions exist, and they also inter-

En ogamy. marry on terms of equality with the Babhans of the North-Western Provinces. Some sections, however, are reckoned inferior to the rest, notably the Hm'aria, Kodarin, and Bhusbarat mentioned above, regarding whom there is a saying in Behar¬

"Hararia, Kodaria, Bhusbarat mare, to Tirhut ka pap hare." In the north of Manbhum the Rampai and Domkatar sections are in such low repute that members of the other sections will not g'ive their daughters in marriage to Rampai or Domkatar men, although they have no obj eotion to taking wives from those sections them¬selves. Consequeutly in that part of the country Rampai and Domkatar Babhans can only get wives from eaoh other, though their women can obtain husbands from all sections except their own. If the restrictions were carried a step further, and Babhans belonging to other sections interdicted from taking Rampai and Domkatal' women to wife, those sections would be wholly cut off from the jus connubii, and would in fact, if not in name, have hardened into a sub-caste. I have no evidence to show that this is at all. likely to take place-the Manbhum practice indeed appears to be qUlte exceptional-but the point deserves notice as tending to throw light on the obscure problem of the formation of sub castes.

Age at Marriage

All Babhans who can afford to do so marry their daughters as At. infants, the bride's age being often no more than four or five years. The same rule holds good for boys, only they are married comparatively later in life, and a son unmarried at the age of puberty does not bring the same sort or reproach on the family as a daughter is supposed to do.

Instances, however, are not wanting where for special reasons the daughters of wealthy families have been married after they were grown up, as was the case with the late Maharani of Tikari; and it seems to be clear that even the most orthodox members of the caste do not take the extreme sacerdotal view of the necessity of infant¬marriage. Ordinarily a price is paid for a bridegroom, but the purchase of brides is by no means uncommon. A man may marry two sisters, and the number of wives he may have is subject to no limit except his ability to maintain them. Some say, however, that a second wife is only permissible if the first proves barren, is con¬victed of unchastity, or suffers from an incurable disease. Whatever may be the rule on the subject, it is raro to find a man with more than two wives. Widows are not allowed to marry again. Divorce is unknown : a faithless wife is simply turned out of the caste and left to shift for herself by becoming a prostitute, turning Mahomedan, or joining some of the less reputable religious sects.

Marriage Cermony

The marriage ceromony of the Babhans does not appear to diller materially from the standard type of a Behar marriage, which has been very y described by Mr. Grierson at page 362 of B ehar Peasant Life. It should perhaps be noted that a Babhan marltwa or marriage shed had six: posts, not four, and that the bride is held throughout the ceremony by a woman of the Rahiu caste. I may further observe that whereas according to TIindu law the completion of the seventh step by the bride renders the marriage final and irrevooable, a number of Babhans in Patna assured me with much particularity of statement that in their opinion sindtwdan, or the smearing of vermilion on the parting of the bride's hair, formed the binding portion of the ceremony-not tho ciroumambulation of the sacrifioial fire (b1uimoar or bedi ghumaeh) , which in Behar takes the place of the Vedic saptapadi. My informants emphasised their statement by adding that if the bridegroom were to die after bMnwm• and before sind",.dan, the bride would not be deemod a widow, and would be permitted to marry another man. In the article on Kumha.r below, I have ondeavoured to trace the origin of sindurdan, and have ventured to put forward the theory that it has probably been borrowed from the marriage servico of the non-Aryan races.

Disposal of the Dead

Babhans burn theil' dead and perform the sraddh. ceremony on the eleventh de.y after doath in the fashion Di~posal of the dca'l, described by Mr, Grierson (Behar P easant Life, page 391). Bairagi Babhans are buried. In cases of extreme poverty the corpse is thrown into a river after the nearest relative has touched the mouth with a burning torch. At the sl'dddh cere-mony,'as in all other acts of domestic worship for which the services of a purohit are required, Kanaujia Brahmans officiate without thereby incurring any degradation in comparison with the Brahmans who serve the higher castes. In some parts of Eastern Behar Maithil Brahmans are employed by the Babhans. These rank below Kanaujias, and are looked down upon by the Srotriya Brahmans, not because they serve in Babhans' houses, but because their own origin is believed to be of doubtful purity.

Religion

The religion of the Biibhan, like that of the ordinary high-caste Hiudu, conforms in its details to the ritual of whatever recognised sect he happens to belong to. Representatives of all sects are found amongst the caste in much the same proportion as in the population at large. Vaishnavism, however, is said to have been only recently introduced among them, and in North Behar most Babhans are either Saivas or Saktas. No social consequences are involved by professing the tenets of any of the regular sects, and intermarriage between their members goes on freely within the limits of the caste. Besides the standard worship which a Babhan performs in virtue of belonging to a particular sect, all householders offer he-goats and rams to Rali on the 24th or 25th of Ruar (September-October), sweetmeats, sandal-paste, flowers to Sitala on the 24th Ohait (March-April), and sugared cakes to Hanuman on every Tuesday.

On the 1st of Chait these three deities are propitiated with pua (wheat-flour and molasses cooked in oil), bara (cakes of ~t1'id fried in oil), and kachwanid (round balls of rice-flour, sugar, and butter) . These offerings are presented by the men of the family without the aid of a Brahman, and are afterwards divided among the members of the household. To the women is relegated the task of appeasing a lower Ol'c!er of gods¬Bandi Mai, Sokha, and Goraiya-with molasses and pilM, a sort of boiled pudding made of sattu or meal.

Social status

Owing probably to the controversy abou.t their origin, the social standing of the Babhans is not altogether easy to determine precisely, and variell slightly in different parts of the area which they inhabit. In South-Eastern Behar they rank immediately below Kayasths, but in Shahabad, Saran, and the N orth-Western Provinces they appear to stand on much the same level as Raj puts. The fact that in Patna and Gya the Amashtha or Karan Kayasths will eat kachcM food which has been cooked by a Babhan, while the other sub-castes of Kayasths will not, may perhaps be a survival from times when Babhans occupied a higher position than they do at the present day. In Champa ran, according to Mr. Beames, Babhans are not permitted to drink and smoke with Brahmans, "and only under some restrictions with "Rajputs.

Thus, a Rajput may eat rice with them only when it is " without condiments; he may not eat bread, and he may drink water "only from an earthen vessel, not from a brass luta. Similarly, when "he eats with them his food must be placed on II dish made of "leaves, and not on the usual brass tltali. The meaning of these "apparently trifling distinctions is that the Rajput, on all emergency, " may eat hastily prepared food with them, but nothing that implies " a long preparation or deliberate intention." B,'tbhans themselveR claim to observe a higher standard of ceremonial puri.ty than Rajputs, in that they will not touch the handle (pariltat/t 01' Zagl/a) of the plough, and that they use the full u,jJC!lIayan ritual when iuvesting their children with the Janeo or sacred thread. In the matter of food they profess to take cooked food only with Brahmans, and sweetmeats , parched rice, etc. (pakkl), from liajputs and the group of castes from whose hands a Brahman oan take water. As regards the latter class, they are careful to explain that, although they will take sweetmeats, &c., as guests in their houses, they will not sit down and eat with them. The Babhan's own diet is the same as that of all orthodox Hindus, and, like theirs, depends in some respects on considerations of sect. Thus Saivas and Saktas eat flesh, while Vaishnavas are restricted to vegetable food. Spirituous liquors are striotly forbidden, and can only be indulged in secretly.

Occupation

The characteristic occupation of the 'Biibhan caste, as indeed is o' indicated by the title Bhui.nhlir, is that of ccupatlOn. settled agriculturists; but the.y will under no circumstances ill•ive the plough with their own hands. Apart from this special prohibition, they do not appear to be unreasonably fastidious as to how they get their li.ving, and will take service as soldiers, constables, durwans, nagdis or l?thials, cut wood, work as coolies, aud do anything that is not specifioally uncle!l.n. Many of them trade in grain, but it is considered derogatory to deal in miscellaneous articles or to go in for general shop-keeping. Some Babhans hold great estates in Behar and the North-Western Provinces, among whom may be mentioned the Maharajas of Benares, of Bettiah in Ohamparan, Tikari in Gya, Hatwa in Saran, and Tamakhi in Gorakhpur, the Raja of Sheohar, and the Rajkumar Babu of Mac1hoban in Ohamparan. They are found as tenure-holders Ot all gra.des, and occupancy and non-occupancy raiyats, while a very few have sunk to the position of landless day¬labourers.

According to their own account, although ranking as as/mil or high caste cultivators, they enjoy no special privileges in respect of rent, and are not particularly sought after as tenants, because, in common with Brahmans, Rajputs and Kayasths, they cannot be called upon for forced labour (begari) or for specifio services in addition to the money-rent. The fact seems to he that, as they will not plough themselves, and therefore must employ labourers (7camiyds) for this pUl'pose, they cannot pay so high a rent as men who work with their own hands ; while their bold and overbearing oharacter, and their tendency to mass themselves in .. strong and pugnacious brotherhoods," render them comparatively uudesirable tenants in the eyes of an exacting landlord. It is said, indeed, that the title Bhuinhar, a term which B<tbhans Il.ever appl1 to themselves, has passed into a by-word for sharpness and cunning.

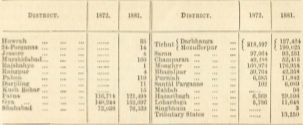

The following statement shows the number and distribution of Babhans as ascertained in the census of 1872 and 1881 ;¬