Badami Cave Temples

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

An overview

Rinku Ghosh, April 29, 2022: The Indian Express

From: Rinku Ghosh, April 29, 2022: The Indian Express

From: Rinku Ghosh, April 29, 2022: The Indian Express

From: Rinku Ghosh, April 29, 2022: The Indian Express

From: Rinku Ghosh, April 29, 2022: The Indian Express

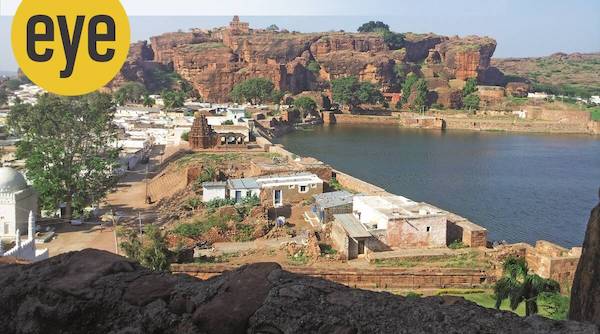

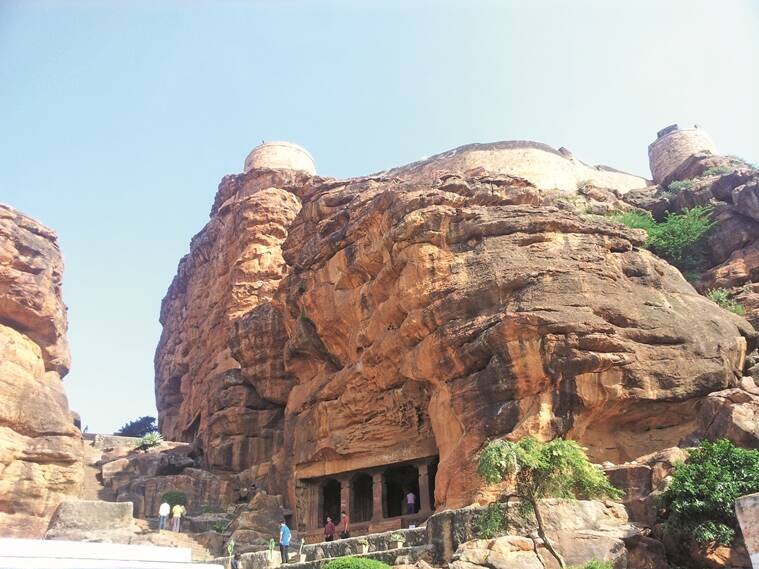

A short drive from town takes us to the soaring volcanic rocks of Badami, so called because they look like giant almonds grown on another planet but piled up haphazardly, terrifying, fiery, burning like embers, breaking through the earth’s crust. It is in these caves that the Chalukyan kings gave full play to the theory that size does matter, the sculpted murals breathing down our puny human lives and overpowering us with their sheer beauty, amid everyday reality. Look at any of the faces here long enough and you would feel they will nod any moment, probably frozen by a spell of some sort. This region saw an efflorescence of the Indic way of life. Both stone and iron age tools and structures at this site indicate that man harnessed iron ore and displayed a rare engineering ability even during the early years of his evolution. By the time of the Chalukyas, who made Badami their capital (mid-6th century), the region had not only become a great hub of commercial activity and wealth but also one of learning. It had found a place in Ptolemy’s A Guide to Geography of the mid-second century. This book contains a brief account of places of commercial importance to the Roman world. So, the Deccan kingdom was economically prosperous, at least from the beginning of the Common Era. The Chalukyas, who unified the Deccan kingdoms between Narmada and Cauvery, and ruled with an unbroken run of stability, patronised a cultural revolution. Be it art, sculpture, literature, performance arts and intelligent discourses, the military might of Pulakesi I and II, as well as Vikramaditya, was overwritten by a certain excellence of the mind.

Consequently, for about 200 years, monuments and temple complexes with the finest of painted and sculpted glory, came up in these parts. The temples, in fact, were not just religious shrines but an assemblage of shared thought, community life, exchange of ideas, celebration of talent and skill, arthouse retreats and collective learning. This liberalism of the Chalukyas has made the temples stand out beyond their spiritual communion even today. “People talk of Hampi. But the Badami hills have a greater life,” say locals.

Dwarfed by the sheer power of the gods, you do understand why Adela Quested ran down the caves in the middle of her solo exploration in A Passage to India. But then there’s a harmony like no other, Shaivaite, Vaishnavite and Jain sculptures find their place in cavernous halls tiered above one another. It is a pure celebration of art forms, beginning with Shiva. He appears in the most frequently carved version of the Natya Shiva, documenting all the postures that make up our Natyashastra. With nine arms on the left and nine on the right, you would find all the 81 postures of Bharatanatyam as we know it. This cave was probably sculpted around 550 AD but the emotions and expressions indicate the sculptor had a fine appreciation of the arts. Why else would we see Ganesha dancing along and even one of the ganas beating the drum. The Nandi bull keeps his head bowed, lost in the sound of music, swaying his head to the beats. Interestingly, Ganesha here is quite fit and doesn’t have a potbelly.

The two fusion forms of Shiva are significant harmony symbols, one as Harihara, half-himself and half-Vishnu, signifying the coming together of two religious sects, and the other of Ardhanarishwara, a surgical union of the male and female halves. The perfect union results in a new, harmonised generation represented by playful children all around, sleeping, crawling, tossing and turning.

The Vishnu cave has lesser sculptures but are more impactful because they seem to be in motion. The patron God of the Chalukyas seems to have been cast in a manner mimicking their courtly demeanour. So, there is Varaha (an avatar of Vishnu), holding Bhudevi (Mother Earth) aloft in one hand, his feet stomping the netherworld, the fury so apparent that it would appear that the mural would crack from side to side. And in sheer desperation and panic, Bhudevi holds on to his tusk to avoid a fall. Equally striking is Narasimha, who, in a rare display of good mood, abandons his destructive anger for a more indulgent half-smile, resting his hand on a royal sceptre. In another unconventional representation, the main figure of Vishnu is seen sitting upright on Sheshnag, not reclining or sleeping, perhaps to endow him with a regal character.

However, good things come in small packages. So, it is with wonder I look at an over 1000-year-old wheel, mounted on a ceiling, with 18 spokes, each of which is a fish. The beautiful yakshis in brackets and niches, seem to be perched like birds ready to step out and resume a conversation they had stopped aeons ago. And in some unhurried ornamentation in a hidden corner, there are colour patches, indicating how these caves were once painted and served as an open-air gallery.

Mahavira sits silent, unmoved by the gust of fresh air from the surrounding Agasthya lake. Time has peeled off the pilaster, the wind has weathered the rocks, the sun has bleached rocks into differing shades of red, the striated layers run into each other, creating their own mosaic. Yet in the end, Mahavira stands tall. Unperturbed and sentient. More than words, the Chalukyan kings still speak to us.