Bahadur Shah Zafar

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Bahadur Shah Zafar: Part I

March 04, 2007

REVIEWS: Through Indian eyes

Reviewed by Ayesha Azfar

IN William Dalrymple’s latest work, Bahadur Shah Zafar seems to be the natural choice for protagonist. For Dalrymple, the last Mughal king embodied the ethos of the city where he spends much of his time. Delhi, with its rich history and multicultural ambience, was the subject of one of his earlier works in which the writer’s fascination for the city combined with an irreverent brand of humour to make for a truly exhilarating reading experience.

But those were still the heady days. Over the years, Dalrymple’s love for Delhi has deepened and matured — and it was perhaps the need to make greater sense of the familiar landmarks of the city’s history that took him to the National Archives of India. Here he found the hitherto unused Mutiny Papers. The key to Delhi’s history during a turbulent era had been found. As Dalrymple and his colleagues sat down to sift through 20,000 Persian and Urdu manuscripts, the plot — the fall of Delhi in 1857 — took on flesh and started to unfold on its own.

In the subcontinent, the joys of research are often unknown. Narratives in history books, clinical in their detail and agonisingly dry, may enrich knowledge but can hardly trigger the capacity to envision a particular era in all its dimensions. This is where Dalrymple’s skills come into play. His picture of mid-19th century Delhi derives from letters and first-hand accounts of the times and also from published historical sources.

Dalrymple takes no pains to hide that he is looking at the tragedy of Delhi through essentially Indian eyes. But there is no shame in that. As an outsider looking in, he does not allow himself to be swayed by staple accounts of the 1857 uprising and empathises with the vanquished, although, as a historian, he may not do full justice to the demands of impartiality.

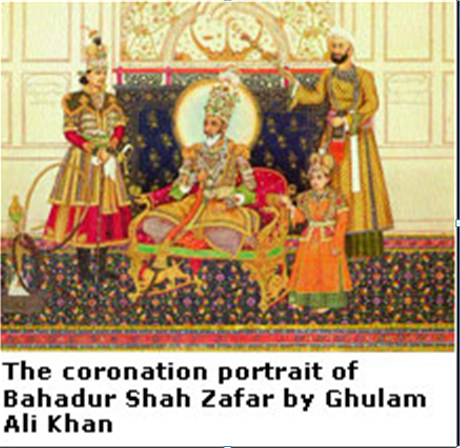

Many have referred to this period as the era of Muslim decline in India, which it was, in the sense that the aristocracy no longer wielded political power and was essentially at the mercy of the British who were viewing their territories with an increasingly acquisitive eye. But was it a really decadent period? Delhi, much like Wajid Ali Shah’s Lucknow in the southeast, resounded with cultural vitality. A poet himself, Zafar patronised art, literature and music, and frequently indulged in the show of grandeur that had marked the reign of his predecessors, even though his personal resources were overstretched and he had to borrow from moneylenders. Although his authority hardly extended beyond the walls of the Red Fort, he was a benign and tolerant king. But times had begun to change, and the previous intermingling between the British and the Indians, so well-documented in Dalrymple’s previous work The White Mughals, was rapidly becoming a thing of the past. Religion, which did not seem to be much of a bar in the marriage of the British resident at the Hyderabad court, James Kirkpatrick, and a Muslim noblewoman Khair-un-Nissa in the previous century, was now propelling the divide.

During the uprising, “some went so far as to term the sepoys mujahedin, even though the overwhelming majority of them were Brahmins”, writes Dalrymple. The British, too, were forming devout views. “In this splendid hall,” wrote one British woman, Mrs Coopland, “which once echoed to the mandates of a despotic Emperor … now echoed the peaceful prayers of a Christian people.” Even the tolerant Zafar had no option but to agree to lead a movement, infused with jihadi sentiments, against the British — a decision that resulted in the brutal murder of his sons and the expulsion of Zafar and some of his family members to Rangoon. In all the hate, there were some voices of sanity, but these went unheard as the British and the Indians indulged in wholesale massacre — described by Dalrymple over several chapters — and the Delhi of Ghalib and Zauq became a battleground. “The land,” wrote Ghalib, who himself had had a narrow escape, “is lampless.”

And yet in the vanquished Zafar remained the sophistication that Delhi was renowned for. He was a broken old man, “dressed in an ordinary and rather dirty muslin tunic … His eyes had the dull, filmy look of very old age … Some heard him quoting verses of his own composition, writing poetry on a wall with a burned stick.” But there was grace in defeat, though not all could understand it. “At our entrance,” wrote the sanctimonious Mrs Coopland, “he laid aside the hookah he had been smoking, and … began salaaming us in the most abject manner, and saying he was ‘burra kooshee’ to see us.”

The book is riveting, and although the minutely described battle scenes can leave one exhausted, Dalrymple succeeds in giving an absorbing picture of Delhi before and during its darkest hour. He brings its citizens — both British and Indian — to life, and creates a link between the past and the present, a tenuous connection that one often forgets in a world of dangerous ideologies. ________________________________________

The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi 1857

By William Dalrymple Bloomsbury.

Available with Liberty Books

Next to Bar B.Q. Tonight, Shop No.

G-1, Plot # GP-5, Block 5, Clifton, Karachi

Tel: 021-5374153

www.libertybooks.com

ISBN 0-7475-8668-3

578pp. Rs895

Bahadur Shah Zafar: Part II

July 08, 2007

Chanting a requiem

Reviewed by Akhtar Payami

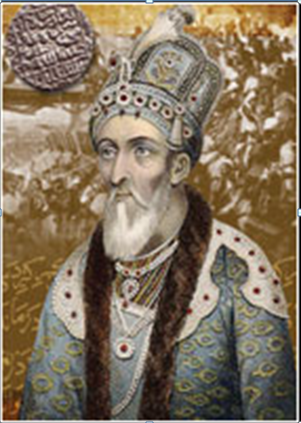

Was he a patriot or a traitor? The controversy has been revived once again as the anniversary of the first war of independence in 1857 is being commemorated all over the subcontinent. While there is no dispute about the enthusiastic response of the people to the cause of freedom, irrespective of their religious belief and ethnic background, the role of the last Mughal emperor of India has been under severe scrutiny. Unfortunately not all historians have been fair to Bahadur Shah Zafar. The reason for the bigoted views of some of them may be attributed to the historical fact that the monarch was a descendant of Taimur whose dynasty continued to rule over a vast kingdom for several centuries.

But Bahadur Shah Zafar was a different phenomenon altogether. Unlike some of his ancestors, he was not a ruthless ruler. Neither was he addicted to a life of ease and comfort like other princes and kings who had ruled before him. He was a Sufi and proudly proclaimed himself to be a ‘dervish’. He often expressed his desire to relinquish his kingship and serve as one of the servants at the shrine of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya. His numerous verses speak eloquently about his distaste for the life of luxury.

Doubts about Bahadur Shah Zafar’s role in the war of independence were created long after his death. Myths were circulated about his queen, Zeenat Mahal Begum’s secret communication to the Englishmen which were contrary to the king’s commitment to the so-called Indian liberation army. Women, particularly those who lived in the protected precincts of the palace, may have been tempted to return to the life of safety and grandeur. But this allegation is not supported by facts. This and many other fictionalised versions of the 1857 rebellion have been corrected by S. Mahdi Husain in his book Bahadur Shah Zafar and the War of 1857 in Delhi.

In his brief preface, leading scholar and Vice Chancellor of Jamia Millia Islamia, Mushirul Hasan, says that the book is of considerable relevance to the historians of Modern India. Rich in details, it offers a dispassionate interpretation of the 1857 revolt and contains rare sketches and documents that shed light on Bahadur Shah’s involvement in the freedom struggle. It would be simplistic to assume that the revolt was generated only on the issue of the cartridges. The wounds were much deeper. The book encompasses the sad and eventful life of a monarch who lived to write his own epitaph.

The portrait of the king as it emerges in the book is that of a kind, courageous and freedom-loving person. The second son of Akbar Shah and his Rajput wife Lal Bai, Bahadur Shah had no communal feelings and firmly believed in the unity of Hindus and Muslims. It was an expression of his devotion to the Sufi traditions and his love for the different segments of the population that he had built a palace called Zafar Mahal to watch the annual Hindu-Muslim fair called Phool waalon ki sair which he had inaugurated himself. The king used to visit the fair regularly.

The author narrates the events that developed into an inspiring battle for freedom launched by Indian sepoys against a powerful opponent. When the rebels approached Bahadur Shah to lead the freedom struggle, the 82-year old monarch found himself incapable of fighting the ‘Firangese’. But on May 10, 1857 when Indian sepoys rose in a body against the British in Meerut, the rebels lost no time in moving to Delhi to meet the emperor. By that time the mutiny had spread to many parts of the city. Two days later they approached Bahadur Shah Zafar and implored him to accept their services in the cause of the Mughal rule which they sought to restore. The emperor accepted their request and along with his sons, Zahiruddin Mirza Mughal and Mirza Jawan Bakht and other able-bodied members of the royal family he went in cavalcade from the fort to Chandni Chowk. ________________________________________ It would be simplistic to assume that the revolt was generated only on the issue of the cartridges. The wounds were much deeper. The book encompasses the sad and eventful life of a monarch who lived to write his own epitaph ________________________________________

It was here that he made his historic announcement endorsing the struggle of the rebels. He said, “I am with you wholeheartedly. But I possess neither a treasure nor an army. If I get back my dominion, I shall bestow gifts on you in right royal manner. The Indian contingents replied that they required neither wealth nor army. They only wanted his support and were prepared to lay down their lives at his feet. The emperor gratefully acknowledged their spirit of freedom and ordered gold coins with the following verse engraved on it: Bazar zad sikka nusrat tarazi/Sirajuddin Bahadur Shah Ghazi (Sirajuddin Bahadur Shah Ghazi issued new gold coins as a sign of victory).

The writer’s objectivity does not suffer throughout the book although his love and admiration for Bahadur Shah never decreases. But those were bad times for the House of Taimur. It would be unkind to ridicule the monarch for his rather unconventional ideas and views. In his essay titled ‘Asbab-i-Ghadar’ Sir Syed Ahmad Khan says, “The ex-king had a fixed idea that he could transform himself into a fly or gnat and that he could in this guise convey himself to other countries and learn what was going on there. He firmly believed that he possessed the power of transformation.” Mahdi Husain thinks that in making this remark about the ex-monarch, Sir Syed was rather much too anxious to disqualify Bahadur Shah as a leader of the country and particularly of the Muslims whom the British held responsible for conspiring against British rule.

Although the king hated the British, his magnanimity never ceased. When the rebels brought 60 English men, women and children to court and sought his permission to kill them, he dissuaded them from killing innocent people. He also ordered the men and women and children to be taken to the fort and to be looked after. Can this act of kindness to his enemies be regarded as treachery?

The treatise contains authentic material on a crucial event in the history of the subcontinent, including the names of the 26 Mughal princes who were executed by order of the Delhi Special Commisioner for rebellion. There is also a list of 15 princes who died shortly after their arrest or subsequent to the pronouncement of a sentence of imprisonment for life. The book also includes the list of 13 Mughal princes who were sentenced to rigorous imprisonment at Agra but were subsequently released and directed to be kept under surveillance at Rangoon, where they lived on a monthly allowance of Rs10 per head.

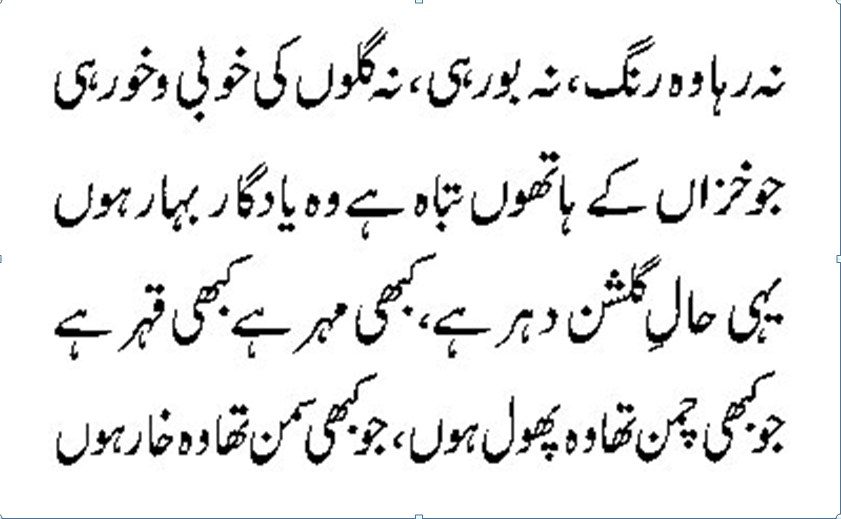

The Mughal Empire lasted for 330 years. The last Mughal emperor was brought to Rangoon in a deplorable condition and imprisoned there. Having suffered through great sorrow and grief he died in 1862. Bahadur Shah Zafar was a broken man at that time he described his own condition in these words:

“Neither has remained that colour, nor that odour; nor have the flowers their former elegance and beauty, I am the momento of that spring which has been ruined at the hands of autumn. Such are the ways of Fate; sometimes it is kind and sometimes indignant. I am the flower of the once-flourishing garden, now reduced to a thorn.”

________________________________________

Bahadur Shah Zafar and the War of 1857 in Delhi By Dr S Mahdi Husain Aakar Books. 28 E Pocket IV, Mayur Vihar Phase I, Delhi-110 091 Tel: 011-2279 5505 aakarbooks@bol.net.in www.aakarbooks.com ISBN 81-87879-91-2 451pp. Indian Rs800

Bahadur Shah Zafar: Part III

July 08, 2007

A people’s war

The book offers a detailed account of the war of 1857, bringing to life Bahadur Shah Zafar who was the rallying point for those who revolted against British rule

Dr S. Mahdi Husain writes about the role of Bahadur Shah Zafar at a critical moment in history

From the account given by Keith [an Eglish writer] it appears that all the reactionary elements rallied to the Emperor, and an army of the people of Dehli — even women and unarmed men — marched to make an attack on the British Camp; they risked their lives in the attempt to take the English batteries. But they failed completely amidst a great slaughter that followed. This army was also joined by Mirza Mughul who started simultaneously with his men to attack the British Camp; but returned, in the words of Jiwan Lal, “without making an attack with the loss of 17 men killed. The guns which Mirza Mughul had mounted in different batteries kept up an incessant fire all day from the MithaiBridge under the command of Mirza Koaish and from Kishanganj under the command of Mirza Abdullah.”

Evidently the war in Dehli had now become the People’s War. The people of Dehli, proper as well as of the villages, were helping the Royal cum Nationalist troops, looking upon them as the Army of Liberation. In his report of August 27, Gauri Shankar, a British spy says, “The people of the village of Nunglee gave great assistance to the rebels and fought side by side with the sepoys. There was a great attack on the (English) Batteries yesterday. Mirza Mughul took out all his Division. The Nasirabad regiments also turned out. There were several Shahzadas present with all the personal troops of the king and the contingents of Nawab Aminu’ddin Khan and Taju’ddin Khan and other nobles of the city. About 50 of them were wounded or killed; and one of the Shahzadas, Ghulam Mustafa, was wounded. There were not sufficient doolies for the wounded, and at last they were carried in, on the crossed muskets of their comrades. The city people are much terrified at the utter defeat of the Neemuch troops and the Army gets more and more dispirited. They have now no hopes of victory. General Bakht Khan’s Division, however, is still confident and hopeful.”

According to another report General Bakht Khan reassembled the fugitives of the Nimuch Brigade and intended to march out again to Najafgarh. Writing on August 28, Turab Ali says, “Yesterday two regiments of Infantry with some ammunition left Dehli for Najafgarh. Shahzada Muhammad Azeem has returned from Hansi and has joined the king’s personal forces. About 20,000 of the country people have got together and have diligently spread reports that they have recovered the 12 guns captured from the Neemuch Brigade and have taken seven of the British guns besides. Yesterday the Neemuch and Bareilly Brigades again started for Najafgarh with eight guns. The cavalry were to start at midnight or early this morning. The infantry and guns have undoubtedly started as the writer further saw them off. Ever since Maulvi Fazl Haq arrived in this city from Alwar, he is unceasingly employed in stirring up the army and the city people against the British. It is likely that an attack on the British batteries will be made to-day. The Shahzadas now turn out in these sorties at the instigation of Maulvi Fazl Haq and usually take their stand on the SabziMandiBridge.”

While Turab Ali gave the above report Gauri Shankar, another British spy, writing on the same day said, “Bakht Khan wishes to make a second attempt to reach Najafgarh but he proposes this time to go round by Gurhee Harsaroo and Gurgaon. The Najafgarh zamindars promise to give him all the assistance, and some zamindars of Panipat and Sonipat are also with him. Bahadur Ali Khan of Bahadurgarh is endeavouring to raise the country and he sends a messenger to Bakht Khan assuring him that the country is on his side. Some Sikhs (also) have been instructed to go to the Punjab to endeavour to raise Manjha in revolt. In the village of Sahni, district Rohtak, Risaldar Khan has collected a large body of insurgent Ranghars. In village Tosham, district Harriyana, there is another body of insurgents and the sowars go off to join them; and many troopers on leave and pensioners of the Government have also collected at this spot where they say there are 20,000 rebellious zamindars. Their object is to plunder Hisar. These risings of the country population are more to be dreaded than a military revolt. Today the city Brigade under the command of Mirza Mughul went out to the batteries at Kishanganj and Qudsia Bagh. In today’s Durbar the zamindars of Nunglee came to complain that they had been punished for assisting the king’s forces. Their villages had been totally destroyed. The king sent them to General Bakht Khan.

The aforesaid report about Maulvi Fazl Haq’s anti-British views and activities which give a clue to his attempts at jihad is reflected in his own writings. But a hidden feature in the picture which the spies could not notice lay in the fact that Fazl Haq shared his views with Emperor Bahadur Shah. On account of his weakness; old age, sainthood and Sufism Bahadur Shah could not speak out like Fazl Haq, but he seized every opportunity that presented itself to encourage the Army.

Writing on September 2 from the city of Dehli, a British spy says, “Yesterday Heera Singh, Brigade Major of the Neemuch force had an audience with the king. The king spoke encouragingly to him and directed him to reorganise the Brigade; and although he could not give such guns as had been lost, he (king) would replace them to the best of his ability. The king has promised to give siege guns. He also bestowed 2,000 rupees upon Heera Singh to make new camp equipage.”

As a result an atmosphere of devotion was created; and to this effect some volunteers wrote to the Emperor, and the Princes also expressed their readiness to go to Panipat in order to intercept the British siege train. In the same spirit, Mirza Mughul wrote a letter assuring the Emperor on his own behalf and also on behalf of others of the common resolve to fight till the end. ________________________________________ When he found the army officers still dissatisfied, he offered all the jewels of the Zenana; and rising from his chair he threw before them the embroidered cushion on which he had been sitting and bid them to take that ________________________________________

“Your Exalted Majesty,” said he, “may keep your mind free from the dread of the enemy. Your slave has personally been staying in the batteries with the Troops for two days; and where the batteries of the infidels were, there they are still. They have made no advance. If their batteries had advanced considerably, they must have come into the city. The whole Army is prepared to slay the infidels, and an attack is about being made immediately...”

But Mirza Mughul was not far-sighted; he did not know that the fall of Dehli was not far off. The British had made active preparations for a big assault on the city of Dehli while the morale of the Badshahi Army, which was never very high, had lowered appreciably since the disaster of Najafgarh. In its ranks differences, always deep-rooted, had leapt to the surface.

Fath Muhammad the British spy says, “The Nasirabad and Neemuch Brigades are supporters of Mirza Mughul and the Bareilly Brigade is devoted to the king. The officers of the Bareilly force and Mirza Mughal are bitter enemies. Every brigade is clamorous; they are actually in want of food. There is not a silver in the Treasury. The Bareilly troops talk of returning to Bareilly. The Bareilly officers, after holding a separate meeting, went to the king. Some of the cavalry said they had gone to ask for the dismissal of Mirza Mughal or for leave to go to Bareilly; and if both these requests were refused, they would commit some violence. What the emperor did to pacify the Bareilly troops is not known. The spies’ reports are incomplete, but they emphasise the split in the Badshahi Army saying, ‘Each cavalry is now split up into ‘Thokes’ — confederacies comprising those who are residents of a particular tract of the country. For instance, Hansi fellows form one ‘Thoke’, the Kalanor men another ‘Thoke’, and so on through the whole body. No one agrees with the other.”

Matters aggravated as days advanced. Perhaps the enemy hand was working secretly in their midst setting them all by the ears and making them all quarrel with their own king as they actually did, demanding their pay under threats of plundering the Palace and the City. “I have 40,000 rupees which you are welcome to take,” said the emperor in an attempt to pacify the quarrelsome heads. Then he added, “There are 101 gold mohurs which were recently presented to me by the Subadar of Bareilly, you might have them too.” When he found the army officers still dissatisfied, he offered all the jewels of the Zenana; and rising from his chair he threw before them the embroidered cushion on which he had been sitting and bid them to take that. Then he went into his private apartments, and brought out jewellery and gave them to the officers saying, “Take this and forget your hunger.” There was such a clear note of sincerity in his word and deed that the hearts of the unprincipled and unyielding soldiers now melted and they were heard to say, “We cannot accept of your Crown jewels, but we are satisfied that you are willing to give your life and property to sustain us.” Thereupon the emperor gave away 40,000 rupees and promised to pay the balance within 15 days; and he made arrangements to raise a loan. ________________________________________

Excerpted with permission from

Bahadur Shah Zafar and the War of 1857 in Delhi

By Dr S Mahdi Husain

Aakar Books. 28 E Pocket IV, Mayur Vihar Phase I, Delhi-110 091

aakarbooks@bol.net.in

www.aakarbooks.com

ISBN 81-87879-91-2 451pp. Indian Rs800

Na Zafar ki qalam ka qusoor hoon, na Muztar kay hi âshaar hoon

(I am not the fault of Zafar's pen; nor am I [a set of] verses written by Muztar)

(qalam= pen, quill; âshaar = verses, being the plural of shér)

In 1960 a low-budget, historical, B film called Lal Qilla (official spelling) caught the attention of the lovers of Hindi- Urdu poetry because of two songs, one [Lagta nahin hai dil mera] certainly and the other [Na Kisi Ki Aankh] ostensibly written by the film’s main character, Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar.

The film’s credit titles are of no help. They have no title card for ‘lyrics’. Instead they have a card saying “songs by Bharat Vyas.”

The confusion was compounded by the extended play gramophone record Lal Qilla/ Babar (Odeon, TAE 1095). On the back cover of the record’s jacket there is no mention of the lyricist. However, the record itself, which carries both the aforesaid songs on Side One, gives the name of just Zafar as the lyricist. This made everyone assume that the emperor wrote both songs. Vividh Bharti would always credit this song to Zafar

Sneha Mahadevan | 'Na Kisi Ki Aankh Ka Noor Hoon was written by my grandfather' | Sep 09, 2015 adds:

<<For decades now there has been confusion about the original writer of Urdu nazm Na Kisi Ki Aankh Ka Noor Hoon, Na Kisi Ke Dil Ka Qarar Hoon. While Bahadur Shah Zafar has been attributed for having written it, a controversy was raised at the behest of Jan Nisaar Akhtar and Javed Akhtar that the ghazal was written by Muztar Khairabadi. After years and years of research, renowned veteran lyricist and poet, Javed Akhtar, grandson of Khairabadi, has found the original copy in the pages of his grandfather’s personal books

<<He says, “He is probably the only poet in India whose work hasn’t been published so I have put it all together. In fact, though the song is very popular as it was in the movie Lal Qilla, and has been sung by so many people, no one really knew the original writer. He was a very versatile man and never repeated himself in his work.”>>

However, Qudsia Gandhi feels that <<It is still debatable.

<<Aqil Ahmad of Ghalib Academy provides a contrarian view from Mumbai-based poet-critic Shamin Tariq. "I don't deny that the ashaar (couplets) that Zafar recited after 1857 have not all been preserved safely. Those of other poets have also been included in them,"

<<Shamim Tariq says, "Some other poets can stake claim on some couplets but the complete ghazal, he adds, does not reflect the helplessness of just one person, but mourns the loss of a whole generation, of the India of old.

<<But that's not unusual. "While [writing a] sher, he would correct it."

<<That, he says, is probably what Khairabadi did with Zafar's ghazal. "He has taken care of its health and balanced it out wonderfully." And maybe he added a few couplets of his own, he says.

<<Here again there are variations. Sometimes the ghazals were known to have five couplets, while Khairabadi's had seven," says Azmi.

<<There is one crucial giveaway. "The last couplet has his Na main Muztar unka habeeb hoon, na main Muztar unka raqeeb hoon; jo palat gaya woh naseeb hoon, jo ujad gaya woh dayaar hoon. (Neither is Muztar her dear, nor is he her confidant; I am the fate that turned bad, the house that got destroyed).

<<But the question about the uncanny similarity in the tone found in Zafar's ghazal reflects that, hence the similarity.

<<In different versions, this Lal Qilla is different from what Khairabadi has written on that yellowing piece of paper, and the version in Khalil-ur-Rehman Azmi's book reads slightly differently. Either the order of the couplets has changed or words have changed their position. In some places, old words have been replaced by new. >>