Balochistan Female Literacy: Pakistan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

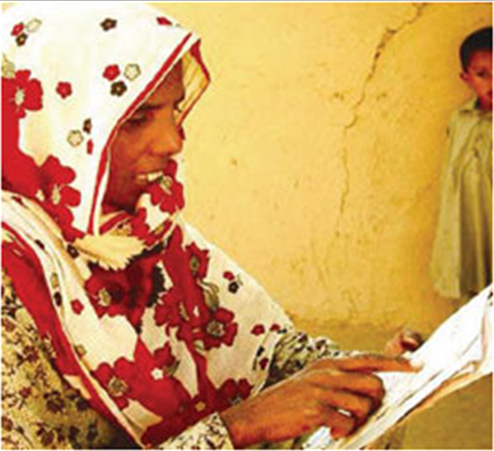

A slow but sure change

By Zofeen T. Ebrahim

Establishing the female literacy programme in the politically volatile province of Balochistan has been a challenge, however, results are promising

“Look at this watch,” entreated 18-year-old Rozina, pulling up her sleeves and holding out her wrist to show a gold watch. “My brother bought it for me after I learnt to tell the time,” explained the beaming teenager, pride written all over. She is among the third batch of 25 women each, who have been enrolled in the adult literacy centre (ALC), in village Bagh Bazar, 142kms from Gwadar.

It is part of National Commission for Human Development (NCHD) ambitious plans to meet the targets of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015.

“It was my brother who insisted we should learn to read and write as my parents were not very keen. Baloch families don’t give importance to imparting education to their daughters,” she further adds.

In a country where the female adult literacy rate is only 28 per cent, according to UN figures, these centres are godsend.

It’s been four months since the written word began to make some sense to Rozina. It has helped her and her elder sister Bakhtawar tremendously with their embroidery work as well.

“We embroider shirt fronts and dupattas and which are taken to Karachi to be sold. Earlier we would memorise the colour schemes for the threads. At times we’d forget and make mistakes which meant doing it all over again. Now we write the names of the colours. We also keep an account now,” Bakhtawar joins in the conversation.

“We write down the expenditure in one column and after keeping a certain profit margin for our labour, write down the amount of the ensemble it should be sold for. Life has become easier,” continues Rozina, as she demonstrates her writing and reading skills.

A fast-track initiative, with a corporate-like public-private partnership approach, the NCHD, was established in 2001, by President Pervez Musharraf, to prop up government departments. At another level it lends support to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as well as elected representatives to overcome challenges and fill gaps in primary education, literacy and provision of basic healthcare services.

Its main objective is finding innovative solutions to achieve the targets set by the MDGs through universal primary education (UPE), adult literacy/gender empowerment programme, reducing population growth, improving infant and maternal mortality, capacity building at grassroots

Halfway towards achieving the eight MDGs, ranked as low as 144 on the UNDP’s human development index, Pakistan needs a quantum leap to remain well on track.

“With dismal development indicators, we needed a new approach to development. We have been told our programmes have a corporate leaning to it. I don’t deny that, but the ultimate objective is to reduce poverty and if it can be done through this, why not,” explains Aamir Bilal, Deputy Director, Public Relations, to a team of media who were taken on a visit to Gwadar to showcase their projects.

So what is the difference between the commission and any other NGO?

“It’s the scale of our work. In just five years, out of a total of 133 (including AJK) we have spread our work in 114 districts of Pakistan,” says Bilal. “We begin by doing a baseline survey in every district we step into. Then we gather information about the situation regarding education, literacy and health. Based on that and after holding a dialogue with the local people to assess their needs, we form a plan to best improve the social indicators of that district. We train the local people, who then take over as we move to other districts.”

For NCHD making mothers literate is a top priority. “It becomes easier in meeting other targets if mothers are literate,” says Waqar Jaffar, Programme Manager in Gwadar.

It’s aim is to ensure that Pakistan’s literacy rate is increased annually by 3.3 per cent per year to achieve the MDG number four from the current 53 per cent (2006) to 86 per cent by the year (2015). Its endeavours were recognised by Unesco last year, when it was awarded the International Reading Association Literacy Prize 2006.

In a way the female literacy programme is intrinsically linked to infant and child healthcare as well. To reduce 30 per cent of deaths in children resulting from diarrhoeal diseases, the commission started a nationwide Oral Rehydration Campaign (ORS). In that rural women are trained to prepare and administer the solution.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has identified ORS as the single most effective life-saving solution in diarrhoea-related diseases to retain the loss of water from the body.

The commission has established over 41,000 literacy centres all over Pakistan from which almost 100,000 women have benefited. It has developed programmes keeping in mind the failures of other such campaigns.

“The emphasis is on cultural relevance and functionality. They should be able to read the newspaper in the local language, write a simple letter and be able to add, subtract, multiply and divide up to three figures. The curriculum is designed in such a way that it corresponds to the curriculum of the children from classes one to three in primary schools. The community is mobilised to give space and choose a teacher from among them whom we train,” says Bilal.

In 2002, the commission began making inroads into the conflict-torn province of Balochistan. Of the 25 districts, it has already covered 23 districts.

“There are 190 ALCs in Gwadar only. A total of 3,204 women have benefited from our literacy programme,” explains Attique-ur-Rehman, Regional Literacy Trainer assigned for three districts in Balochistan. “Establishing a foothold has been quite a challenge. Convincing the community to send their children to school and the females to study has been quite an uphill task,” he acknowledges.

“There have been political threats, too,” concedes Jafar. Despite the odds, he can already feel the change among the women. “But I’d like you to see it for yourself.”

“Four months ago, if I’d met you, I would’ve just stuttered and not even been able to see you in the eye. Today, not just me, but all of us,” says Rozina, waving her hand over the class of 25 females of various age groups from 15 to 50, “are composed and confident.”

With big, light brown eyes, Nazal, 28, adds: “I know I’m too old to study but I just want to say that what I have learnt from this centre is more than what these books teach us. I learnt the importance of education and I will ensure that all five of my children complete their studies, come what may,” she says resolutely.

Her eldest, a son is 12 and the youngest is a six-month old daughter. “I’ve also learnt to use my son’s cell phone and often call up relatives in Karachi,” she adds triumphantly.

Weather-beaten Rabia, a diabetic and a grandmother of two, is the oldest pupil in the class. “I was curious to know what others were learning. Today if you tell me to take a bus from my town to another, I can do so myself. I can read the numbers on the bus, even the name of the town. I won’t need to cajole my son to come with me anymore if I travel.” She insists she can go to Karachi on her own!

Their teacher, 25-year-old Fazila, who runs the ALC in her home is not only a graduate, but a government-appointed Lady Health Volunteer (LHV).

“It’s not just about being able to read and write. They have learnt other things, too, especially matters relating to personal hygiene. This is my third batch and it’s really gratifying to see how much these women have changed in such a short time.”

According to the teacher, they have begun to talk softly; learnt to read expiry dates on medicines; pay a little more attention to their grooming, their hair is neatly tied in plaits and they have started wearing clean clothes when they come here.

“At the home front too, there is a visible change. Because I visit their homes as the LHV, I’ve noticed that they cover the food, drink boiled water and if that is not possible, at least boil it for the infants. Many can now read the Holy Quran. Those who already knew the Holy Quran, found it easier to learn to read and write.”