Bareilly District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts.Many units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Bareilly District (Bareli)

District in the Bareilly or Rohilkhand Division, United Provinces, lying between 28° 1' and 28° 54' N. and 78° 58' and 79° 47' E., with an area of 1,580 square miles. It is bounded on the north by Naini Tal ; on the east by Pilibhit and Shahjahanpur ; on the south by Shahjahanpur and Budaun ; and on the west by Budaun and the State of Rampur. The District of Bareilly, though lying not far from the outer ranges of the Himalayas, is a gently sloping plain, with no greater variety of surface than is caused by the shifting channels of its numerous streams. Water lies almost everywhere near the surface, giving it a verdure that recalls the rice-fields of Bengal.

The most prominent physical feature is the Ramganga River, which traverses the south-western portion. Its channel has a well-defined bank at first on the south, and later on the north ; but except where the stream is thus confined, the khadar or lowland merges imper- ceptibly into the upland, and the river varies its course capriciously through a valley 4 or 5 miles wide, occasionally wandering to a still greater distance. North of the Ramganga are numerous streams running south to meet that river. The chief of these (from west to east) are the Dojora, which receives the Kichha or West Bahgul, the Deoranian, the Nakatia, and the East Bahgul, which receives the Pangaili. The Deoha forms the eastern boundary for some distance.

The gentle slope of the country makes it possible to use these rivers for irrigation in the upper part of their courses. Lower down, and more especially in the east of the District, they flow below the general level and are divided by elevated watersheds of sandy plains.

The District exposes nothing but alluvium, in which even kankar or calcareous limestone, is scarce.

The flora resembles that of the Gangetic plain generally. In the north a few forest trees are found, the semal or cotton-tree (Bombax malabaricum) towering above all others. The rest of the District is dotted with fine groves of mangoes, while jamun (Eugenia Jambolana), shisham (Dalbergia Sissoo), tamarind, and various figs (Ficus glomerata, religiosa, infectoria, and indica) are also common. Groves and villages are often surrounded by bamboos, which flourish luxuriantly. The area under trees, which is increasing, amounts to about 32 square miles.

Leopards are frequently found in the north of the District, and wolves are common in the east. Antelope are seen in some localities, and parha or hog deer haunt the beds of rivers. The ordinary game- birds are found abundantly, and fish are plentiful. Snakes are also very numerous.

The climate of the District is largely influenced by its proximity to the hills, Bareilly city and all the northern parganas lying within the limits of the heavier storms. The rainy season begins earlier and continues later than in the south, and the cold season lasts longer.

The north of the District is unhealthy, on account of excessive moisture and bad drinking-water. The mean temperature varies from 54° to 60° in January, and from 85° to 93° in May, the hottest month.

The annual rainfall in the whole District averages nearly 44 inches ; but while the south-west receives only 39, the fall amounts to nearly 47 inches in the north and exceeds 48 in the north-east. Fluctuations from year to year are considerable; in 1883 less than 19 inches was received, and in 1894 nearly 65 inches. Before the Christian era the District was included in the kingdom of Northern Panchala ; and the names are known, from coins found at Ramnagar, of a number of kings who probably reigned in the second century b.c. These kings were connected by marriage with a dynasty ruling in the south of Allahabad, and it has been suggested they were the Sunga kings of the Puranas1 A kingdom called Ahichhattra, in or near this District, was visited by Hiuen Tsiang in the seventh century A.D., and is described as flanked by mountain crags. It produced wheat and contained many woods and fountains, and the climate was soft and agreeable.

In the early Muhammadan period the tract now known as Rohilkhand was called Katehr, and the Rajputs who inhabited it gave continual trouble. Shahab-ud-din, or his general Kutb-ud-din, captured Bangarh in Budaun District about the year 1194 ; but nothing more is heard of the Muhammadans in this neighbourhood till Mahmud II made his way along the foot of the hills to the Ramganga in 1252. Fourteen years later, Balban, who succeeded him, marched to Kampil, put all the Hindus to the sword, and utterly crushed the Katehriyas, who had hitherto lived by violence and plunder. In 1290 Sultan Firoz invaded

1Journal, Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1897, p. 303; A. Cunningham, Coins of Ancient India.

Katehr again, and brought the country into final subjection to Musalman rule, which was not afterwards disputed except by the usual local revolts. Under the various dynasties which preceded the Mughal empire, the history of Katehr consists of the common events which make up the annals of that period : constant attempts at independence on the part of the district governors, followed by barbarous suppression on the part of the central authority. The city of Bareilly itself was founded in 1527 by Bas Deo and Barel Deo, from the latter of whom it takes its name. It was, however, of small importance till the reign of Shah Jahan, when it took the place of Budaun. In 1628 All Kuli Khan was governor of Bareilly, which had grown into a considerable place. In 1657 Raja Makrand Rai founded the new city of Bareilly, cut down the forest to the west of the old town, and expelled all the Katehriyas from the neighbourhood. A succession of regular governors followed during the palmy days of the great Mughal emperors; but after the death of Aurangzeb, in 1707, when the unwieldy organization began to break asunder, the Hindus of Bareilly threw off the imperial yoke, refused their tribute, and commenced a series of anarchic quarrels among themselves for supremacy.

Their dissensions only afforded an opportunity for the rise of a new

Muhammadan power. All Muhammad Khan, a leader of Rohilla

Pathans, defeated the governors of Bareilly and Moradabad, and made

himself supreme throughout the whole Katehr region. In 1744 the

Rohilla chieftain conquered Kumaun right up to Almora ; but two

years later the emperor Muhammad Shah marched against him, and

Ali Muhammad was taken a prisoner to Delhi. However, the empire

was too much in need of vigorous generals to make his captivity a long

one, and in 1748 he was restored to his old post in Katehr. Next year

he died, and a mausoleum at Aonla, in this District, still marks his

burial-place. Hafiz Rahmat Khan, guardian to his sons, succeeded to

the governorship of Rohilkhand, in spite of the crafty designs of Safdar

Jang of Oudh, who dispatched the Nawab of Farrukhabad against him

without effect. Hafiz Rahmat Khan defeated and slew the Nawab,

after which he marched northward and conquered Pilibhit and the

tarai. The Oudh Wazir, Safdar Jang, plundered the property of

the Farrukhabad Nawab after his death, and this led to a union

of the Rohilla Afghans with those of Farrukhabad. Ahmad Khan of

Farrukhabad defeated Nawal Rai, the deputy of Safdar Jang, besieged

Allahabad, and took part of Oudh ; but the Wazir called in the aid of

the Marathas, and with them defeated Ahmad Khan and the Rohillas

at Fatehgarh and at Bisauli, near Aonla. He then besieged them for

four months at the foot of the hills ; but owing to the invasion of

Ahmad Shah Durrani terms were arranged, and Rahmat Khan became

the de facto ruler of Rohilkhand.

After the accession of Shuja-ud-daula as Nawab of Oudh, Rahmat Khan joined the imperial troops in their attack upon that prince, but the Nawab bought them off with a subsidy of 5 lakhs, Rahmat Khan took advantage of the victory at Panipat in 1761 to make himself master of Etawah, and during the eventful years in which Shuja-ud-daula was engaged in his struggle with the British power, he continually strengthened himself by fortifying his towns and founding new strongholds. In 1770 Najib-ud-daula advanced with the Maratha army under Sindhia and Holkar, defeated Rahmat Khan, and forced the Rohillas to ask the aid of the Wazir. Shuja-ud-daula became surety for a bond of 40 lakhs, by which the Marathas were induced to evacuate Rohilkhand. This bond the Rohillas were unable to meet, whereupon Shuja-ud-daula, after getting rid of the Marathas, attacked Rohilkhand with the help of a British force lent by Warren Hastings, and subjugated it by a desolating war. Rahmat Khan was slain, but Faiz-ullah, the son of Ali Muhammad, escaped to the north-west and became the leader of the Rohillas. After many negotiations he effected a treaty with Shuja-ud- daula in 1774, by which he accepted nine parganas worth 15 lakhs a year, giving up all the remainder of Rohilkhand to the Wazir (see Rampur State). Saadat Ali was appointed governor of Bareilly under the Oudh government. In 1794 a revolution in Rampur State led to the dispatch of British troops, who fought the insurgents at Bhitaura or Fatehganj (West), where an obelisk still commemorates the slain. The District remained in the hands of the Wazir until 1801, when Rohilkhand, with Allahabad and Kora, was ceded to the British in lieu of tribute. Mr. Henry Wellesley, brother of the Governor-General, was appointed President of the Board of Commissioners sitting at Bareilly, and after- wards at Farrukhabad. In 1805 Amir Khan, the Pindari, made an inroad into Rohilkhand, but was driven off. Disturbances occurred in 1816, in 1837, and in 1842 ; but the peace of the District was not seriously endangered until the Mutiny of 1857.

In that year the troops at Bareilly rose on May 31. The European

officers, except three, escaped to Naini Tal ; and Khan Bahadur, Hafiz

Rahmat Khan's grandson, was proclaimed Nawab Nazim of Rohilkhand.

On June 11 the mutinous soldiery went off to Delhi, and Khan Bahadur

organized a government in July. Three expeditions attempted to attack

Naini Tal, but without success. In September came news of the fall

of Delhi. Walidad Khan, the rebel leader in Bulandshahr, and the

Nawab of Fatehgarh then took refuge at Bareilly. A fourth expedition

against Naini Tal met with no greater success than the earlier attempts.

On March 25, 1858, the Nana Sahib arrived at Bareilly on his flight from Oudh, and remained till the end of April ; but the rebellion at Bareilly had been a revival of Muhammadan rule, and when the com- mander-in-chief marched on Jalalabad, the Nana Sahib fled back again into Oudh. On the fall of Lucknow, Firoz Shah retired to Bareilly, and took Moradabad on April 22, but was compelled to give it up at once.

The Nawab of Najibabad, leader of the Bijnor rebels, joined him in the city, so that the principal insurgents were congregated together in Bareilly when the English army arrived on May 5. The city was taken on May 7, and all the chiefs fled with Khan Bahadur into Oudh.

Ahichhattra or Ramnagar is the only one of many ancient mounds in the District which has been explored. It yielded numerous coins and some Buddhist sculptures. It is still a sacred place of the Jains. The period of Rohilla rule has left few buildings of importance ; but some tombs and mosques are standing at Aonla and Bareilly.

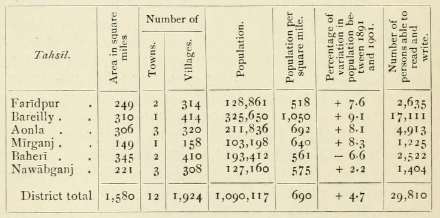

There are 12 towns and 1,924 villages. Population has risen steadily during the last thirty years. The numbers at the last four enumera- tions were as follows: (1872) 1,015,041, (1881) 1,030,936, (1891) 1,040,949, and (1901) 1,090,117. The District is divided into six tahsils — Faridpur, Bareilly, Aonla, Mirganj, Baheri, and Nawabganj — the head-quarters of each being at a place of the same name. The principal towns are the municipality of Bareilly and Aonla. The following table gives the chief statistics of area and population in 1901 :

Hindus form 75 per cent, of the total and Musalmans 24 per cent., while Christians number 7,148 and Aryas 1,228. The density is much higher than the Provincial average, and the rate of increase between 1891 and 1901 was larger than in most parts of the United Provinces. More than 99 per cent, of the population speak Western Hindi, the ordinary dialect being Braj.

The most numerous Hindu caste is that of Chamars (leather-workers and cultivators), 100,000. Other castes numerically strong in this Dis- trict are : Kurmis (agriculturists), 94,000 ; Muraos (market-gardeners), 73,000 ; Kisans (cultivators), 67,000 ; and KAhars (cultivators and water-carriers), 56,000. Brahmans number 48,000 and Rajputs 38,000.

Ahars, who are found only in Rohilkhand, but are closely allied to the Ahirs of the rest of the Provinces, number 46,000. Daleras (1,724), who are nominally basket-makers but in reality thieves, are not found outside this District. Among Muhammadans, Shaikhs number 54,000 ; Julahas (weavers), 41,0005 and Pathans, 41,000. The Mewatis, who number 9,000, came from Mewat in the eighteenth century, owing to famine. Banjaras, who were formerly army sutlers and are still grain- carriers, have now settled down to agriculture, chiefly in the submontane Districts, and number 9,000 here. About 66 per cent, of the popula- tion are supported by agriculture, 6 per cent, by personal services, and 4 per cent, by general labour. Cotton-weaving by hand supports 3.5 per cent. Rajputs, Pathans, Brahmans, Kayasths, and Banias are the largest landholders. Kurmis occupy nearly a quarter of the total area as cultivators, while Ahars, Kisans, and Brahmans each cultivate about 7 or 8 per cent.

There were 4,600 native Christians in 1901, of whom 4,488 were Methodists. The American Methodist Episcopal Mission was opened here in 1859, and has ten stations in the District, besides a theological college at Bareilly city.

The north of the District contains a damp unhealthy tract, where rent rates are low and population is sparse, while cultivation depends largely on the season. The central portion is extremely fertile, consisting chiefly of loam, with a considerable proportion of clay in the Mirganj and Nawabganj tahsils. In the south, watersheds of sandy soil divide the rivers; but these sandy strips are regularly cultivated in the Bareilly and Aonla tahsils, while in Faridpur much of the light soil is very poor and liable to be thrown out of cultivation after heavy rain. The alluvial strip along the Ramganga is generally rich, but is occasionally ruined by a deposit of sand. Excluding garden cultivation, manure is applied only when the turn comes round for sugar-cane to be grown, at intervals of from 3 to 8 years.

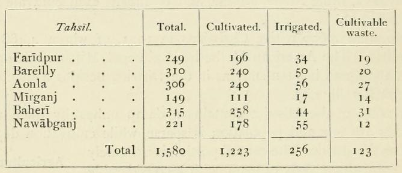

The tenures are those common to the United Provinces. Zamindari or joint Zamindari tenures prevail in 5,547 mahals, 503 are perfect or imperfect pattiddri, and 36 are bhaiyachara. The District is thus chiefly held by large proprietors. The main agricultural statistics for 1903-4 are shown in the table on the next page, in square miles.

The principal food-crops, with their areas in square miles in 1903-4, are : rice (237), wheat (368), gram (201), bajra (166), and maize (115). Sugar-cane covers 71 square miles, and is one of the most important products; while poppy (23), oilseeds (27), cotton (13), and san-hemp (10) are also valuable crops.

The total cultivated area has not varied much during the last thirty years ; but there has been a permanent increase to the west of Aonla and north of Faridpur tahsils, which is counterbalanced by a temporary decrease in the north of the District owing to vicissitudes of the seasons.

The principal changes in cultivation have been directed towards the sub- stitution of more valuable crops for inferior staples. The area under bajra has decreased, while sugar-cane, rice, and maize are more largely grown. Poppy has been reintroduced recently, and the area sown with it is increasing. A rise in the area producing barley and gram points to an increase in the area double cropped. Very few loans are taken under the Land Improvement Loans Act; between 1890 and 1903 the total amounted to Rs. 41,000, of which Rs. 38,000 was advanced in the famine year, 1896-7. Nearly 3/2 lakhs was lent under the Agricul- turists' Loans Act, of which Rs. 63,000 was advanced in 1896-7. In good seasons the advances are small.

The cattle used for agricultural purposes are chiefly bred in the Dis- trict or imported from the neighbouring submontane tracts, those bred in Pilibhit being called panwar. These varieties are small but active, and suffice for the shallow ploughing in vogue. Stronger animals, used in the well-runs in the south-west of the District, are imported from west of the Jumna. Horse-breeding is confined to the Ramganga and Aril basins, where wide stretches of grass and in some places a species of Oxalis resembling clover are found. Four pony and two donkey stallions are maintained by Government and by the District board, and two donkey stallions are kept on estates under the Court of Wards to encourage mule-breeding. There has, however, been little progress in either horse or mule-breeding. Sheep are not kept to any great extent.

The soil of the District is generally moist, and in ordinary seasons there is very little demand for irrigation of the spring crops. In the north, where a regular supply of water is valued for rice and sugar-cane, the Rohilkhand canals are the main source. Elsewhere, wells, rivers, and Jhils are used. In 1903-4 canals and wells supplied 76 and 75 square miles respectively, tanks or Jhils 58, and other sources (chiefly rivers) 47. The canals are all small works and may be divided into two classes. Those drawn from the Bahgul, Kailas, Kichha, and Paha have permanent masonry head-works, with channels dug to definite sections, and are provided with subsidiary masonry works, regulators, &c., like the regular canals of the Doab. The others are small channels, into which water is turned from the rivers by earthen dams, renewed annually. Masonry wells are not constructed for irrigation, except by the Court of Wards. In most parts of the District the wells are temporary excavations worked by pulley, or by a lever, as the spring- level is high ; but in some tracts to the south water is raised in a leathern bucket by a rope pulled by bullocks or by men.

Kankar or nodular limestone is scarce and of poor quality. A little lime is made by burning the ooze formed of lacustrine shells.

Trade and communication

The most important industry of the District is sugar-refining. This is carried on after native methods, which are now being examined by the Agricultural department in the hope of eliminating waste. Coarse cotton cloth and cotton carpets or daris are woven largely, and Bareilly city is noted for the production of furniture. A little country glass is also manufactured.

The Rohilkhand and Kumaun Railway workshops employed 81 hands in 1903, and a brewery in connexion with that at Naini Tal is under construction. The indigo industry is declining.

Grain and pulse, sugar, hides, hemp, and oilseeds are the chief exports, while salt, piece-goods, metals, and stone and lime are imported. The grain is exported to Calcutta, and sugar is sent to the Punjab, Rajputana, and Central India. Bareilly city and Aonla are the chief centres of trade.

The main line of the Oudh and Rohilkhand Railway passes through the south of the District, with a branch from Bareilly city through Aonla to Aligarh. The north is served by the Rohilkhand and Kumaun Rail- way, which is the only route to the hill-station of Naini Tal, and by a line through Pilibhit and Sitapur to Lucknow, which leaves the Rohil- khand and Kumaun Railway at Bhojupura, a few miles north of Bareilly city. Another metre-gauge line, recently opened, leads from Bareilly south-west through Budaun to Soron in Etah District.

The total length of metalled roads is 139 miles and of unmetalled roads 186 miles. Of the former, 125 miles are in charge of the Public Works department, but the cost of all but 88 miles is met by Local funds. There are avenues of trees along 254 miles. The District is not well supplied with roads. Those which are metalled follow roughly the alignment of the railways, and there are no others, except the road from Aonla to Budaun. In the north communication is almost im- possible during the rains ; but the streams can easily be forded in the hot and cold seasons.

Bareilly is not liable to severe famine, owing to the natural moisture of the soil and the rarity of so complete failure of the rains as occurs elsewhere. It is also well served by railways, and a considerable portion can be irrigated. Ample grazing- grounds for cattle are within easy reach. In 1803-4 distress was felt, and the spring crops were grazed by the cattle as no grain had formed. In 1819 and 1825-6 there was scarcity. The famine of 1837-8 followed a succession of bad years, and its effects were felt, but not so severely as in the Doab. While famine raged elsewhere in 1860-1, Bareilly suffered only from slight scarcity, owing to the failure of the autumn harvest ; and relief works, which were opened for the first time, alleviated distress. Relief works were also necessary in 1868-9, i877-8, and 1896-7, but the numbers attracted to them never rose very high.

Administration

The Collector is usually assisted by a member of the Indian Civil Service, and by four Deputy-Collectors recruited in India. There is a tahsildar at the head-quarters of each tahsil. The Executive Engineer of the Rohilkhand division (Roads and Buildings) and the Executive Engineer of the Rohilkhand Canals are stationed at Bareilly city.

There are three regular District Munsifs and a Subordinate Judge, and the appointment of Village Munsifs commenced recently. The District and Sessions Judge of Bareilly has civil and criminal jurisdic- tion in both Bareilly and Pilibhit Districts. Crime is very heavy, especially offences affecting life and grievous hurt. Religious feeling runs high, and quarrels between Hindus and Muhammadans, accom- panied by serious rioting, are not infrequent. The thieving caste of Daleras has already been mentioned. Female infanticide is now very rarely suspected, and in 1904 only 130 names remained on the registers of proclaimed families.

Under the Rohillas proprietary rights did not exist, and villages were farmed to the highest bidder. After annexation in 1801 Rohilkhand was divided into two Districts, Moradabad and Bareilly. Shah- jahanpur District was formed in 1813-4; Budaun was carved out of both the original Districts in 1824 ; the south of Naini Tal District was taken away in 1858, and sixty-four villages were given, as a reward for loyalty, to the Nawab of Rampur. Pilibhit was made a separate Dis- trict in 1879. In the early short-term settlements the Rohilla system of farming was maintained till 1812, when proprietary rights were con- ferred on persons who seemed best entitled to them. The demand then fixed was so high that heavy balances were frequent, and many estates were abandoned. A more enlightened method of settlement based on a survey was commenced under Regulation VII of 1822, and the first regular settlement followed under Regulation IX of 1833. Different methods were adopted by the officers who carried this out. Some divided each village into circles according to soil and situation, while others classified villages according to their general condition as a whole. Rent rates were sometimes assumed for the various soils, while in other cases general revenue rates were deduced from the collections in previous years. The revenue fixed amounted to 11 lakhs on the present area. Another settlement was made in 1867-70. The rental ' assets ' were calculated from rent rates selected after careful inquiry. A large area was grain-rented ; and the rent rates for this tract were selected after an examination of the reputed average share of the land- lord, and after experiments in the out-turn of various crops, the average prices for twenty years being applied to ascertain the cash value. The result was an assessment of 13-5 lakhs ; but this was reduced by about Rs. 4,000 in 1874-6, owing to the assessment of too large an area in the north of the District, where cultivation fluctuates. The latest revision was carried out in 1898-1902. Cash rents were then found to be paid on about two-thirds of the total cultivated area, and the actual rent-roll formed the basis of assessment. Rents of occupancy tenants had remained for the most part unaltered since the previous settlement, and enhancements were given where these were inadequate. Grain rents, chiefly found in the north of the District, were largely commuted to cash rates. The demand fixed amounts to 15 lakhs, representing 45 per cent, of the net 'assets,' and the incidence falls at Rs. 1-7 per acre, varying from Rs. 1.3 to Rs. 2 in different parts.

There is one municipality, Bareilly City, and ten towns are ad- ministered under Act XX of 1856. Outside of these, local affairs are managed by the District board, which has an income of 1.7 lakhs, chiefly from rates. In 1903-4 the expenditure on roads and buildings amounted to Rs. 63,000.

There are 22 police stations and 19 outposts, all but one of the latter being in Bareilly city. The District Superintendent of police has under him an assistant and 4 inspectors, besides a force of 112 subordinate officers and 587 men of the regular police, 374 municipal and town police, and 1,989 village and road chaukidars. The Central jail, which has accommodation for more than 3,000 prisoners, contained a daily average of nearly 1,800 in 1903, while the District jail contained 715. The latter was formerly used for convicts from Nain! Tal and from Pilibhit, and is a Central jail for female prisoners.

The District takes a medium place as regards the literacy of its inhabitants, of whom 2.7 per cent. (4.7 males and o.6 females) can read and write. The number of public institutions increased from 143 in 1880-1 to 154 in 1900-1, and the number of pupils from 5,033 to 6,675. I" i9°3~4 there were 196 such institutions, with 9,636 pupils, of whom 996 were girls, besides 163 private schools with 2,479 pupils. Of the total, 3 were managed by Government, and 136 by the District and municipal boards, while 55 were aided. There is an Arts college at Bareilly city. In 1903-4 the expenditure on education was a lakh, of which Rs. 53,000 was derived from Local and municipal funds, Rs. 23,000 from fees, and Rs. 12,000 from Provincial revenues.

There are 13 hospitals and dispensaries, with accommodation for 287 in-patients. In 1903 the number of cases treated was 114,000, of whom 3,068 were in-patients, and 2,815 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 30,000, most of which was met from Local and municipal funds. There is a lunatic asylum at Bareilly city with about 400 inmates.

In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 36,000, representing a proportion of 33per1,000 of the population. Vaccina- tion is compulsory only in Bareilly city.

[District Gazetteer (1879, under revision); S. H. Fremantle, Settle- ment Report (1903).]