Barua, Behar

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

Contents |

Barua, Behar

A mixed caste in the names of the two castes engaged in Bengal and Behar, respectively, in the cultivation of piper betel, ordinarily known as pan (Sansk. parna) , tlte leaf par excellence. Although their occupation is the same, provincial and linguistio distinctions separate the Bengali-speaking Barui of Bengal and the Hindi-speaking Barai of Behar into two entirely distinct castes, who do not intermarry or eat together, and whose domestic usages differ in important particulars. They will therefore be separately treated here.

Origin and internal structure

Regarding the origin of the Baruis of Bengal several traditions are current. The popular legend represents them as specially created by Brahma in order to relieve the Brahmans from the labour of growing betel, which was found to interfere with their religious duties. The Jati-Mali makes them the offspring of a Tanti woman by a man of the Goaia ca te, while the Brihadharma Purana describes their father as a Brahman and their mother as a Sudra. Other traditions assign to them a Kshatriya or Kayasth father and a Sudra mother_ At the present day the Baruis are divided into four endogamous sub-castes :-(1) Rarhi, (2) Barendra, (3) Nathan, (4) Kota. Within these again we find a number of the standard Brahmanical gotras. 'The latter groups, however, appear to be mainly ornamental, for maniage in most places is allowed with persons belonging to the same gotJ'a, provided they are not Samanodakas. As the fact of their belonging to this class would in any case have been a conclusive bar to marriage, it follows that the sections are exogamous only in theory, and we may assume that they were borrowed dignitatis causa from tho system of the higher castes_ It may further be surmised that the Barui caste is made up of members of various respectable castes, who were drawn together by the common occupa¬tion of betel-growing, and is not, as many castes undoubtedly are, a homogeneous offshoot from a single caste or tribe. The contradictory character of the legends regarding its origin, in which several different castes figure, tends on the whole to bear out this view

Marriages

Baruis marry their daughters as infants, forbid widows to marry again, and do not allow divorce. Polygamy is admitted only in the sense that a man may marry a second wife when the first proves barren. Hypergamy is unknown, and a bride-price is paid to the parents of the bride. certain families enjoy the hereditary rank of Gostipati, or head of a clique or party within the caste; but this involves no restrictions on marriage, and the members of suoh families give their daughters in marriage to ordinary Baruis. 'rho marriage ceremony of the Birui differs little from that in use among Brahmans, except that the rite of Kusandndika is not always insisted upon. After the gift and acceptance of the bride, the bridegroom stands behind her, and, taking her hands in his, lifts an earthen vessel containing parched pn.ddy, ghee, plantains, and betel leaves. and pours the contents on a fire kindled with straw. Tho couple then make obeisanoe to Agni, and the ceremony is held to be complete.

Religion

In matters of religion the Baruis follow the usages of all orthodox Hindus. Most of them belong to the Sakta sect, and a few are Vaishnavas. Saivism is said to be unknown among them. For all the standard offices of religion they employ Brahmans, who stand on an equal footing ,with the Brahmans who serve the other members of the Nava.sak group. In some places they have also special ceremonies of their own. On the 4th of Baisakh (April-May) the patroness of betel cultivation is worshipped in some places in Bengal with offerings of flowers, rice, sweetmeats, and sandal-wood paste. Along the banks of the Lakhya in Eastern Bengal the Baruis celebrate, without a Brahman, the Navami Puja in honour of Ushas (,Hooc;, Amora) on the ninth of the waxing moon in Asin (September-October). Plantains, sugar, rice, and sweetmeats are placed in the centre of tho pan garden, from which the worshippers retire, but after a little return, and, carrying out the offerings, distribute them among the village children. In Bikrampur the deity invoked on the above date is Sungal, one of the many forms of Bhagabatl. The reason given by the Baruis for not engaging the services of a Brahman is the following :-A Brahman was the first cultivator of the betel. 'Through neglect the plant grew so high that he used. his sacred thread to fasten up its tendrils, but as it still shot up faster than he could supply thread, its charge was given to a Kayasth. Hence it is that a Brahman cannot enter a pan garden without defilement.

Occupation

At the present day some Baruis have taken to trade, while others are found in Government service or as members of the learned professions. The bulk of the caste, however, follow their traditional occupation. Betel cultivation is a highly specialised business, demanding considerable knowledge and extreme care to rear so delicate a plant. The pan garden (bam, barej) is regarded. says Dr. Wise, as an almost sacred spot. Its greatest length is always north and south, while the entrances must be east and west. The enclosure, generally eight feet high, is supported by hijul (Sansk. ijjala, Barringtonia acutangula) trees or betel-nut palms. the former are cut down periodically, but the palms are allowed to grow, as they cast little shade and add materially to the profits of the garden. 'The sides are closely matted with reeds, jute stalks, or leaves of the date or Palmyra palm, while nal grass is often grown outside to protect the interior from willd and the sun's rays. The top is not so carefully covered ill, wisps of grass being merely tied along the trellis work over the plants. A slopillg footpath leads down the centre of the enolosssure, towards which the furrows between the plants trend, and serves to drain off rain as it falls, it being essential for the healthy growth of the plant that the ground be kept dry.

The pan plant is propagated by cuttings, and the only manures used are pakmatl, or decomposed vegetable mould excavated from tanks, and khali the refuse of oil-mills. The plant being a fast growing one, its shoots are loosely tied with grass to upright poles, while till'ice a year it is drawn down and coiled at the root. As a low temperature injures the plant by discolouring the leaves, special care must be taken during the cold season that the enclosure and its valuable contents are properly sheltered. Against vermin no trouble is required, as caterpillars and insects avoid the plant on accouut of its pungency. Weeds are carefully eradicated, but certain culinary vegetables, such as pepper, varieties of pumpkins, and cucumbers, patwal Trichosanthes dioeca), and baigun (egg-plant, Solallum melolgena) , are permitted to be grown. Pan lertves are plucked throughout the year, but in July and August are most abundant, and therefore cheapest; while a garden, if properly looked after, continues productive from five to ten ycars. Four pan leaves make one gfluda, and the bim, or measure by which they are sold, now-a-days contains in Eastern Bengal twenty gandas, although formerly it contained twenty-four. In the Bluiti couutry (Bakar¬ganj), thirty-six gandas go to the bim. Pan leaves are Bever retailed by the Barui himself, but are sold wholesale to agents (paikars), or directly to the pan-sellers.

The varieties of the piper betel are numerous, but it is probable that in different districts distinct names are given to the same species. 'The Kafuri or eamphor-scented prill, allowed by all natives to be the most delicately flavoured, is only grown at Sunar¬gaon in Dacca and Mandalgbat ill Midnapur for export to Calcutta, where it fetches a fancy price. The next best is the sunchi, which often sells for four annas a bIra. This is of a pale green colour, and if kept for a fortnight loses in pungency and gains flavour. 'The commoner sorts are the desi, bangala, bluztial, dhaldogga, ghas pan, grown best in Bakarganj, and a very large-leaved variety called bubna. The usual market price of the inferior kinds is from one to two pice a bira.

It has been mentioned that the bam is regarded as almost sacred, and the superstitious practices in vogue resemble those of the Silk-worm breeder. The Barui will not enter it until he has bathed and washed his clothes, while the low-caste man employed in digging is required to bathe before he commences work. Animals found inside are driven out, while women ceremonially unolean dare not enter within the gate. A Brahman never sets foot inside, and old men have a prejudice against entering it. It has, however, been known to be used for assignations. At the present day individuals belong ing to the Dhoba, Chandal, Kaibartta, sunri, and many higher and lower castes, as well as Muhammadans, manage pan gardens, but they omit the ceremonies necessary for preserving the bam clean and unpolluted.

Social status

The social standing of the Ba.ruis is sufficiently defined by stating that they belong to the Nabasak. They eat goats, deer, pigeons, fish, and the leavings or Brahmans, and drink country spirits. They will drink with Kaibarttas, and smoke in their company, but will not usc the same hookah. In respect of their relations to the land their position is fairly high. Some have risen to be zamindars, others are tenure-holders or substantial occupancy raiyats. Instances of their having come to be day-labourers or nomadic cultivators are so rare as to be practically unknown.

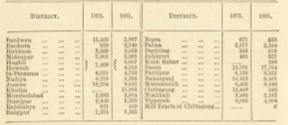

The following statement shows the numbers and distribution of the Baruis in 1872 and 1881 :-

Marriages

The Barai of Behar bear the title Raut, and are divided into the following sub-castes:-(I) Maghaya, (2) Jaiswar, (3) Chaurasia, (4) Semerya, (5) Sokhwa. They have only two sections, Kasyapa and Nag, and regulate their marriages by the formula of prohibited degrees already quoted. Marriage is both infant and adult, the M . former being deemed more respectable. Widow¬ marriage is permitted by the sagai form. The widow may marry her late husband's younger brother, but is not• com¬pelled to do so. If, however, she marries an outsider, she forfeits all claim to share in her deceased husband's property, and the custody of her children usually rests with his family. A man may marry two wives, but not more. Divorce is not recognised: indiscretions within the caste are winked at; but a women who goes wrong with an out-sider is turned out of the caste, and probably ends hv becoming a regular prostitute. It will be observed that the practice of widow-marriage and the recognition of adult-marriage for females sharply distinguish the Barai from the Barui, and are sufficient of themselves to form a conclusive bar to intermarriage between the two group . Curiously enough, the standard tradition regarding the origin of the Barai alleges that they were formerly Brahmans, who were turned out of the sacred caste because they allowed widows to marry again.

Religion

Most Barais are Hindus of the Sakta sect. Their minor gods are Mahabirji (Hanuman), Bandi, Goraiya and Sokhli. The last mentioned is held in special reverence and awe, and it is believed that when his worship is neglected great disasters come upon the pan garden. Maithil, Kanojia, and Srotri Brahmans are employed by the Barai in the worship of the greater' gods; the di minores being usually propitiated by the members of the family without the intervention of Brahmans.

Occupation

Betel cultivation is the main business of the Barai, to which they add the preparation of lime and khair or katth,l an astringent extract from the wood of several species of acacia (Acacict catechu, Willd., the kurz'; Acacia suma, Kurz, acsundra, D.C., and probably more).l For a description of the methods of betel-growing followed in Behar, I may refer to Grierson's Behar Peasant Life, pages 248-49. the statement on page 249, that" the betel-nut, which is the fruit of the areca catechu, is called supari or or sopal'i," seems to require correction. The following extracts from Colonel Yule's Glossary put the matter in a olear light :¬.

Betel

The leaf of the piper betel, L., chewed with the dried areca-nut (which is thence improperly called betel-nut, a mistake as old as Fryer-1673-see page 40), chunam, etc., by the natives of India and the Indo-Chinese countries. The word is Malayal. rettila, i.e. '1:e1'U + ila = ' simple or mere leaf,' and comes to us through the Port. be.tre and betle."

Pawn

The betel-leaf. Hind. pan, nom the Sansk. parna, 'a leaf.' It is a North-Indian term, and is generally used for the combination of betel, areca-nut, lime, etc., which is politely offered (along with otto of roses) to visitors, and which intimates the termination of the visit. This is more fully termed pawn-sooparie (supari is Hind. for areca)."

Areca

The seed (in common parlance the nut) of the palm, Areca catechu. L., commonly, though somewhat improperly, called 'betel-nut'; the term betel (q.v.) belonging in reality to the teaf, which is chewed along with the areca. Though so widely cultivated, the palm is unknown in a truly indigenous state. The word is Malayalan adakka, and comes to us through the Portuguese."

Social status

In Beames' edition of Elliot's glossary , vol. ii, p. 231 s.v. Bira, the ingredients of pan-supari are stated, on the authority of the Kanun-i-Islam, to be "betel leaves, area or betel-nut, catechu, quick¬lime, aniseed, coriander seed, cardamoms, and cloves." Barais rank with the acharani castes of Behar, and Brahmans can take water and sweetmeats from their hands. Their diet is that of the average ortho-dox Hindu. Unlike the Barui of Bengal, they will not eat the leavings of Brahmans, nor will they drink spirituous liquors. The Barhi and Lohar are the lowest castes from whom a Barai will take water or sweetmeats. Cooked food, of course, they will only eat with people of their own caste and sub-caste. As regards their agricultural position, few of them appear to have risen above the status of occupancy raiyat.

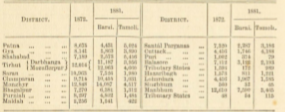

The following table gives tho number and distribution of the Barais and Tambulis or Tamolis in 1872 and 1881. In the former year the figures of both castes are included, and in the latter they are shown separatoly, so that.absolutely accurate statistics cannot be prepared :¬