Bedar

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Contents |

Bedar

A Small castc of about I 500 persons, belonging notice. J.Q ^j^qI^^ Khandcsh and Hyderabad. Their ancestors were J^indaris, apparently recruited from the different Maratha castes, and when the Pindaris were suppressed they obtained or were awarded land in the localities where they now reside, and took to cultivation. The more respectable Bedars say that their ancestors were Tirole Kunbis, but when Tipu Sultan invaded the Carnatic he took many of them prisoners and ordered them to become Muhammadans. In order to please him they took food with Muhammadans,

1 Based on a paper by Rao Sahib Mr. Adiiriim Chaudhri of the Gazetteer Dhonduji, retired Inspector of Police, office. Akola, and information collected by

and on this account the Kunbis i)ut them out of caste until they should purify themselves. But as there were a lar^^e number of them, they did not do this, and have remained a separate caste. The real derivation of the name is unknown, but the caste say that it is be-dar or ' without fear,' and was i^iven to them on account of their bravery. They have now obtained a warrant from the descendant of Shankar Acharya, or the high priest of Sivite Hindus, permitting them to describe themselves as Put Kunbi or purified Kunbi.^ The community is clearly of a most mixed nature, as there are also Dher or Mahar Bedars.

They refuse to take food from other Mahars and consider themselves defiled by their touch. The social position of the caste also presents some peculiar features. Several of them have taken service in the army and police, and have risen to the rank of native officer ; and Rao Sahib Dhonduji, a retired Inspector of Police, is a prominent member of the caste. The Raja of Surpur, near Raichur, is also said to be a Bedar, while others are ministerial officials occupying a respectable position. Yet of the Bedars generally it is said that they cannot draw water freely from the public wells, and in Nasik Bedar constables are not con- sidered suitable for ordinary duty, as people object to their entering houses.

The caste must therefore apparently have higher and lower groups, differing considerably in position. They have three subdivisions, the Maratha, Telugu and 2. Sub- Kande Bedars. The names of their exogamous sections are anT'°"^ also Marathi. Nevertheless they retain one or two northern marriage customs, presumably acquired from association with the ^^^ °"^^' Pindaris. Their women do not tuck the body-cloth in behind the waist, but draw it over the right shoulder. They wear the choli or Hindustani breast-cloth tied in front, and have a hooped silver ornament on the top of the head, which is known as dJwra. They eat goats, fowls and the flesh of the wild pig, and drink liquor, and will take food from a Kunbi or a Phulmali, and pay little heed to the rules of social impurity. But Hindustani Brahmans act as their priests. Before a wedding they call a Brahman and worship him as a god, the ceremony being known as Deo Brahman. The ' Mr. Marten's C.P. Census Report (19 11), p. 212. rites.

Brahman then cooks food in the house of his host. On the same occasion a person specially nominated by the Brahman, and known as Deokia, fetches an earthen vessel from the potter, and this is worshipped with offerings of turmeric and rice, and a cotton thread is tied round it.

Formerly it is said they worshipped the spent bullets picked up after a battle, and especially any which had been extracted from the body of a wounded person. 3. Funeral When a man is about to die they take him down from his cot and lay him on the ground with his head in the lap of a relative. The dead are buried, a person of importance being carried to the grave in a sitting posture, while others are laid out in the ordinary manner.

A woman is buried in a green cloth and a breast-cloth. When the corpse has been prepared for the funeral they take some liquor, and after a few drops have been poured into the mouth of the corpse the assembled persons drink the rest. While following to the grave they beat drums and play on musical instruments and sing religious songs ; and if a man dies during the night, since he is not buried till the morning, they sit in the house playing and singing for the remaining hours of darkness. The object of this custom must presumably be to keep away evil spirits. After the funeral each man places a leafy branch of some tree or shrub on the grave, and on the thirteenth day they put food before a cow and also throw some on to the roof of the house as a portion for the crows.

Bedar: Deccan

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Origin

Bedar, Bendar, Berad — the great hunting and, agricultural tribe of the Carnatic, identical with the Boyas of Telingana ana the Ramoshis of the Marathawada. They call themselves Kanayamkula descendants of Kanayam," Dhorimkulam " children of chiefs " and Valmika Kshatriyas " Kshatriyas descended from Valmiki." They are a wild and fierce looking people, of coarse features and dark complexion, and bear an evil reputation as highway robbers and dakaits. Their predatory habits have been greatly repressed, and they are now largely employed as village watchmen. ••

The word Bedar is derived from Byaderus, a corruption c of Vyadherus (Sansk- Byadha, a hunter). The origin of the tribe has been the subject of many legends. According to one they are descended from the primitive pair, Kannayya and Kanakavva who are fabled to have sprung from the right and left eyes of Basvanna respectively. The Bedars claim descent also from Valmiki, who is represented In the Purdnds as being reclaimed from his pernicious and marauding habits by the divine sage Narad. But the legend which is very widely current among them, states that from the thigh of the dead king Hoti of the Solar race was produced, by the great Rishis, a black dwarf, ugly in appearance and ferocious in habits. Being unfit to rule, he was driven by the sages into the jungles to live on forest produce or by hunting. In his wanderings he once met Menika, a celestial nymph of matchless beauty, and made love to her. Their union was blessed with seven sons : — "

from whom sprang the following seven great clans of Bedars, bearing the names of their progenitors : —

(1).Nishadas, who hunted tigers, bears and wild boars and ate the flesh of buffaloes.

(2) Sheras, who made a living by selling jungle roots, fruit

and sandalwood {Sanialum album).

(3) Kavangriyaris, who wore long hair and had their ear-lobes bored with large holes. They subsisted on the sale of m biold (Pterocarpus marsupium) and oyster shells.

(4) Salikas, who were employed as day labourers in digging • wells and tanks.

(5) Ksharakaris, who made lime and salt.

(6) Ansaris, who were fishermen and worked also as ferrymen.

(7) Sheshatardharis, who were hunters and fowlers.

All these seven clans were distinguished by their respective gotrq names or bedigd —

(1) Gojaldaru or Gujjar.

(2) Gosalru or Gurral.

(3) Bhadmandalkaru.

(4) Saranga Gunda Bahsarandlu or Sarang Gauda.

(5) Tayarasamantaru or Tair Samant.

(6) Pingal Rangamanya.

(7) Rajadhiraj (Maharaja).

This elaborate organisation appears to be traditional and to have no bearing upon the present social division of the tribe.

Early History

The Bedars were a Southern India tribe and came into the Deccan under their leader Kalappa Naik early in the sixteenth century. They first settled at Adhoni and Dambala, situated in the Raichur Duab, which was then a bone of contention between Krishna Raylu, the king of Vijayanagaram, and Ismail Adil Shah, the Sultan of Bijapur. The Bedars, taking advantage of the disturbed times, raided and plundered the country far and wide, so that, for the ti*ie being, they* were tine terror of the surrounding districts. Partly by colonisation and partly 4)y con- quest, they gradually extended their territories until, under Pam Naik 1. (1674-1695), they founded a State, and fixed their capital at Vakinagir, two mrles west of Shorapur. Pam Naik was the bravest of the dynasty and helped Sikandar Adil Shah, the last of the Bijapur Sultans, in subduing his rebel nobles and in his wars with the Generals of Aurangzeb. The Sultan, in gratitude, granted him a magnificent jagir and conferred upon him all the insignia of royalty with the titles " Gajag Bahirand Gaddi Bahari Bahadur." Pam Naik styled himself Raja, a title which has since descended to his successors. He organised the State, dividing it into provinces, over which he appointed Subedars. He was also a great builder, and raised new forls, constructed roads and tanks, and bu^It stately temples. It was in his time that the kingdoms of Bijapur and Golconda were subdued by Aurangzeb. In his successor, Pid Naik Bahari (1695-1725 A.D.), the power of the Bedars had reached its zenith. He strongly resisted the power of Aurangzeb, and defeated the Imperial forces in pitched battles. At last the Emperor took the field in person and besieged the Bedar strong-hold of Vakingira. The fort made a galant stand, but was reduced ulti- mately by Zulfikarkhan, the best of Aurangzeb's Generals. It was, however, retaken by the Bedars immediately on the departure of Aurangzeb. Pid Naik removed the seat of government from Vakingira to Shorapur, which he founded on a hill. He introduced many reforms and ruled the State in greater splendour than any of his predecessors. After a glorious reign of 31 years he died in 1726 A.D. The later history of the Shorapur Rajas is blended with that of the Nizams of Hyderabad, whom they acknowledged as their suzerain lords, paying an annual tribute of 1,45,000 rupees. Though brave, they were not able rulers and were not infrequently involved in the wars of the Nizams with the Marathas and other contemporary powers. The decline of the State had already com- menced and was hastened by internal dissensions, mal-administration and reckless extravagance, until, after a brief revival under the administration of Colonel Meadows Taylor, it was confiscated ont account of the rebellion of the Raja '-Venkatappa Naik against the British Government (1858), and ceded to H. H. the Nizam in 1860 A.D.

Internal Structure

The internal structure of the Bedars is very intricate. This is due, partly to the large area over which they are scattered, and partly to the different social levels that have been formed among them. Thus at the highest level are the Rajas and rich landholders who have, in every respect, assumed the' style of higher Hindu castes, while the lowest level is occupied by the bulk of the people who adhere to their aboriginal customs and usages and have few scruples in diet — eating beef, as well as catj and other ^inclean animals. The following endogamous groups are found among them : —

(1) sadar or Naikulu (Valmika) Bedars.

(2) Tanged Bedars.

(3) Mangala Bedars.

(4) Chakla Bedars.

(5) Neech Bedars.

(6) Basavi Bedars.

(7) Ramoshi Bedars.

(8) Jas Bedars.

(9) Bedars (proper).

Of these, the Naikulu sub-tribe, called also Naikulu Maklus, claim the highest rank and decline to hold any communion either of food or of matrimony with the other sub-tribes. To this sub-tribe the Bedar Rajas of Shorapur and other principalities belong. The Mangala Bedars are barbers and the Chakla Bedars washermen to the Bedar tribes and have, in consequence of their occupation, formed separate groups. Neech Bedars are known to abstain from eating fowl or drinking shendi, the fermented sap of the wild date palm. They do not touch the shendi tree, nor sit on a mat made of its leaves. Basavi Bedars are the progeny of Basavis, or Bedar girls dedicated to the gods and brought up, subsequently, as prosti- tutes. They form a separate community comprising (1) children of unions, by regular marriage, between the sons and daughters of Basavis, (2) the children of Basatis themselves.' While among other Bedar tribes Basavis are made in pursuance of vows ot Ancient family customs, among Basavi Bedars there is a rule under which each family is said to be bound to offer up one of its girls to thj gods as Basavi. The daughters of Basaois, for whom husbands cannot be procured in their community, are wedded to swords or idols. On an auspicious day, the girl to be dedicated is taken, m procession, to the temple, bearing on her head a lighted lamp. After she has been made to hang a garland round the sword or the idol, a tali (mangalsutra) is tied round her neck and her marriage with the sword or the idol is complete. She is, thenceforward, allowed to consort with any man provided that he is not of a lower caste },han herself. A Basaoi girl is entitled to share, equally with her brothers, the property of her father or mother. The euphemistic n,-me Basavi originally denoted girls who were dedicated to Ba^vanna, the deified founder of the Lingayit sect, but the title is, at the present day, borne by a girl dedicated to any god.

The Ramoshi Bedars are found in large numbers in the Marathawada districts. They are, no doubt, a branch of Bedars who appear to have migrated to the Maratha country after their Settle- ment in the Carnatic. This view is supported by a tradition which states that they came into Maharashtra under the five sons of Kalappa Naik. In their features and customs, but especially in their predatory tendencies, they have preserved the characteristics of their race. They .regard, with pride, the Raja of Shorapur as the head of their clan. Like their brethren in the Carnatic, they were highly valued for their military qualities, filled the armies of Shiva ji and his successors, and distinguished themselves as brave soldiers. During the last century they gave a good deal of trouble to British officers, but they have now settled down as industrious cultivators. Their social status among the Maratha castes is very low, for even their touch is regarded as unclean by the respectable classes. They appear to have broken off all connection with the Carnatic Bedars and form at present an independent group. They talk Marathi in their houses. The word ' Ramoshi ' is a local name and is supposed to be a corruption of Rama-vanshis "descendants of Rama" or ^of Ranwashis, meaning dwellers of foissts.' Bedars (proper) occupy the lowest*" level among the tribe. They cling to their aboriginal usages, eating beef and canion and worshipping animistic deities. They carry Margamma Devi on their heads in a box, and subsist by begging alms in her name.

The Boyas, as the Bedars are designated in Telingana, are divided into (I) Sadar Boy a and (2) Boy a, corresponding to the Sadar Bedars and the Bedars of the Carnatic. It is also said that they have only two main divisions (i) Nyas Byadrus, (2) Gugaru Byadrus, the members of which neither eat together nor intermarry.

The Bedars are said to be divided into 101 exogamous sections, numbers of which are of the totemistic type, although the totems do not .appear to be respected.

Marriage in one's own section is strictly forbidden, The marriage o4 two sisters to the same husband is permitted, provided the elder is married first. Two brothers may marry two sisters and a man may marry the daughter of his elder sister.

A member of a higher caste may gain admission into the Bedar community by paying a fine to the tribal Panchayat and by providing a feast for the members of the community. On the occasion, the proselyte is required to eat with them and subsequently to have a betel -nut cut on the tip of his tongue. After the meals he is required to remove all the plates.

Marriage

The Bedars marry their daughters either as infants, or after they have attained the age of puberty. Sexual indis- cretions before marriage are tolerated and are condoned only by a slight punishment. Should a girl become pregnant before marriage her seducer is compelled to marry her. Cohabitation is permitted, even though the girl has not attained sexual maturity. Polygamy is recognised and a man may marry as many wives as his means allow him to maintain.

The marriage ceremony of the Bedars comprises rituals which correspond closely with those in use among other local castes. A suitable girl having been selected, and preliminary arrangements and ceremonies concluded, a marriage pandal of five pillars of shevri (Sesbania agyptiaca) is erected in the court-yard of the bridegroom's house. On the arrival of the bride at the bridegroom's house the bridal pair are seated on a platform, built, under the wedding bower, with ant-hill earth, and are rubbed over with turmeric paste by five married females. Previous to the wedding, four earthen vessels, filled with water, are set at the comers of a square space prepared outside the booth, and are connected with a cotton thread. A fifth vessel, also filled with water, is kept in the centre of the square, and covered with a burning lamp. The bridal pair, with their sisters, are seated opposite to this lamp, and made to undergo ceremonial ablution. Dressed in new wedding garments, with their brows adorned with bashingams, and the ends of their clothes knotted together, the bride and bride- groom are led immediately to a seat under the booth and are w^ded by Brahmans who hold an antarpdt (a silk curtain) between the pair, pronounce benedictory mantras and shower rice and grain over their heads. Mangalsutra, or the lucky bead necklace, is hanied round to be touched by the whole assembly, and tied, in the presence of the caste Panchayat, by the bridegroom round the bride's neck. The couple are then led round, making obeisance first to the gods, then to the Panchas and lastly to the elderly relatives. The ceremony next in importance, and purely of a Kulachar character, is Bhrnnd, cele- brated on the 3rd day after the wedding. A conical heap ei cooked rice, crested with twenty wheat cakes and a quantity of vegetables, is deposited on a piece of white cloth under the wedding pandal. Before this sacred heap, frankincense is burnt and offerings of eleven betel -leaves and nuts and eleven copper coins are made. After two handfuls of this food have been handed to the bridal pair, eleven married couples mix the food with sugar and ghi and eat it. After the meal is over, five of them touch, with their hands soiled with food, the bodies of the wedded pair who, thereupon, are required to cast away the lumps of food they held in their hands. The cele- bration of the Dandya ritual on the 4th day, and the bestowal of a feast to the relatives and friends, bring the nuptial proceedings to a close. It is said that Bedars abstain from drink during the four days of the marriage ceremony.

Except among respectable families, a Bedar widow is allowed to marry again, but not the brother of her deceased husband. She may, however, re-marfy the husband t>f her elder sister. The price for a widow is Rs12 and is generally paid to her parents. The ceremony is of a, simple character. At night the parties repair to Hanuman's temple, where the bride is presented with a new white sari, a choli (bodice) and some bangles. After the widow has put on these, her proposed husband ties pusti (a bead necklace) about her neck. The assembly then return to the bridegroom's house. Next day a feast is given to the members of the tribe in honour of the event.

Divorce

Divorce is recognised by those who allow their widows to re-marry. A divorced woman can claim alimony from hv husband if it be the latter's fault that led to the divorce. If a woman goes wrong with a man of a lower caste she is turned out of her community. Liaison with a man of a higher caste is tolerated, and condoned only by a small fine. Divorced women are permitted to marry again by the same rite as widows.

Inheritance

In matters of inheritance, the Bedars follow the Hindu law. The usage of Chudawand obtains among them. Under this usage the property is divided equally among wives, provided they have sons. A Basavi girl (dedicated to the gods) shares 'equally with her brothers.

Religion

In point of religion, the Bedars are divided into Vaishanavas and Saivas. The Vaishnavas worship Vishnu and his incarnations of Rama and Shri Vyankatesh. The Shivas pay homage to the god Siva and generally abstain from all work on Mondays, in honour of the deity. Some of the Bedars follow the tenets of Lingayitism, do reverence to Basava in the form of a bull, and employ jangams as their priests. The favourite deity with Basavi Bedars is Shri Krishna, in whose honour a great festival is held on the Janmashtami day (the 8th of the light half of Shravana). But the special deities of the tribe are Hanuman ar)d Ellama, worshipped on Saturday, when the Bedars abstain from flesh. Their principal festivals are Dassera in Aswin (October- November) and Basant Panchmi in Magh (February-March), which are celebrated with great pomp and ceremony. Pochamma (the smallpox deity), Mariamma (the goddess presiding over cholera), Maisamma, Balamma, Nagamwia (the serpent* goddess) and a host of minor gods and spirits are also appeased with offerings of animals.

The worship of departed souls is said to prevail among the tribe.

Child=Birth

A woman, after child-birth, is unclean for five days. As soon as the child is born, its umbilical cord is cut by the mid- wife, and buried underground on the 3rd day after birth. Brahmans are employed for religious and ceremonial purposes.

Disposal of the Dead

The Vaishanava Bedars burn their dead in a lying posture, while the Saivas bury them in a sitting posture with the face turned towards the east. Members of res- pectable families perform Srddha on the 12th and 13th days, and generally conform to the funeral rites in vogue among the Brahmans.

Social Status

The social status of the Bedars is not easy to define. The great Zamindars and Rajas occupy an" eminent position in the caste and are looked upon with respect, while even the touch of the Ramoshi Bedars is regarded as unclean. Village wells are open to them for water and temples are open to them for worship. Concerning their diet they have few scruples — eating beef, pork, fowl, jackals, rats, lizards, wild cats, in short all animals except snakes, dogs and kites. They eat carrion and indulge freely' in spirituous and fermented liquors. They do not eat the leavings of any caste.

Occupation

The Bedars believe their original occupation to be hunting and military service. Peaceful times and the introduc- tion of game laws have compelled them to take to agriculture. They are also employed as village watchmen and messengers and discharge their duties faithfully. As agriculturists, a few have risen to the position of great land-lords and jdgirdars. The bulk are either occupancy and non-occupancy ryots or landless day-labourers.

Panchayat

The Bedars have a strong tribal Panchayat known as Katta. The head of the Panchayat is called Kattimani and has authority both in religious and social matters. All social, religious and ceremonial points and disputes are referred to this body for decision, and judgments passed by it are irrevocable and enforced on pain of loss of caste. A woman accused of adultery, or of eating food from a member of an inferior caste, is expelled from the community arfd is restored anly on her head being shaved and the^rap of her tongue branded with a live coal of the rui plant. 1% the case of the ?nan, his head and face are clean shaved. Both are required to bathe and their bodies are sprinkled over with some spirits, upon which they become purified.

Note

Cohabitation and pregnancy before marriage are tolerated, and condoned by the girl's marriage with her paramour. Every woman is compelled to be tatooed.

Distribution

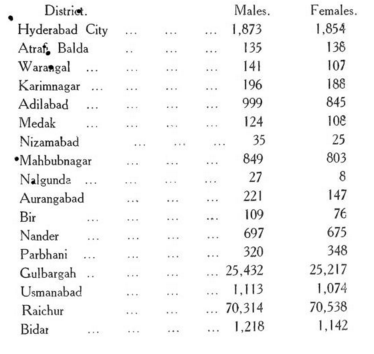

The following statement shows the number and distribution of Bedars in 1911 : — ■