Bedar or Boya

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Bēdar or Bōya

Throughout the hills,” Buchanan writes,43 “northward from Capaladurga, are many cultivated spots, in which, during Tippoo’s government, were settled many Baydaru or hunters, who received twelve pagodas (£4 5s.) a year, and served as irregular troops whenever required. Being accustomed to pursue tigers and deer in the woods, they were excellent marksmen with their match-locks, and indefatigable in following their prey; which, in the time of war, was the life and property of every helpless creature that came in their way. During the wars of Hyder and his son, these men were chief instruments in the terrible depredations [181]committed in the lower Carnatic. They were also frequently employed with success against the Poligars (feudal chiefs), whose followers were of a similar description.” In the Gazetteer of the Anantapur district it is noted that “the Bōyas are the old fighting caste of this part of the country, whose exploits are so often recounted in the history books. The Poligars’ forces, and Haidar Ali’s famous troops were largely recruited from these people, and they still retain a keen interest in sport and manly exercises.”

In his notes on the Bōyas, which Mr. N. E. Q. Mainwaring has kindly placed at my disposal, he writes as follows. “Although, until quite recently, many a Bōya served in the ranks of our Native army, being entered in the records thereof either under his caste title of Naidu, or under the heading of Gentu,44 which was largely used in old day military records, yet this congenial method of earning a livelihood has now been swept away by a Government order, which directs that in future no Telegas shall be enlisted into the Indian army. That the Bōyas were much prized as fighting men in the stirring times of the eighteenth century is spoken to in the contemporaneous history of Colonel Wilks.45 He speaks of the brave armies of the Poligars of Chitteldroog, who belonged to the Beder or Bōya race in the year 1755.

Earlier, in 1750, Hyder Ali, who was then only a Naik in the service of the Mysore Rāja, used with great effect his select corps of Beder peons at the battle of Ginjee. Five years after this [182]battle, when Hyder was rising to great eminence, he augmented his Beder peons, and used them as scouts for the purpose of ascertaining the whereabouts of his enemies, and for poisoning with the juice of the milk-hedge (Euphorbia Tirucalli) all wells in use by them, or in their line of march. The historian characterises them as being ‘brave and faithful thieves.’ In 1751, the most select army of Morari Row of Gooty consisted chiefly of Beder peons, and the accounts of their deeds in the field, as well as their defence of Gooty fort, which only fell after the meanness of device had been resorted to, prove their bravery in times gone by beyond doubt. There are still a number of old weapons to be found amongst the Bōyas, consisting of swords, daggers, spears, and matchlocks. None appear to be purely Bōya weapons, but they seem to have assumed the weapons of either Muhammadans or Hindus, according to which race held sway at the time. In some districts, there are still Bōya Poligars, but, as a rule, they are poor, and unable to maintain any position. Generally, the Bōyas live at peace with their neighbours, occasionally only committing a grave dacoity (robbery).46

“In the Kurnool district, they have a bad name, and many are on the police records as habitual thieves and housebreakers. They seldom stoop to lesser offences. Some are carpenters, others blacksmiths who manufacture all sorts of agricultural implements. Some, again, are engaged as watchmen, and others make excellent snares for fish out of bamboo. But the majority of them are agriculturists, and most of them work on their own putta lands. They are now a hard-working, industrious people, who have become thrifty by dint of their industry, [183]and whose former predatory habits are being forgotten. Each village, or group of villages, submits to the authority of a headman, who is generally termed the Naidu, less commonly Dora as chieftain. In some parts of Kurnool, the headmen are called Simhasana Bōyas. The headman presides at all functions, and settles, with the assistance of the elders, any disputes that may arise in the community regarding division of property, adultery, and other matters. The headman has the power to inflict fines, the amount of which is regulated by the status and wealth of the defaulter. But it is always arranged that the penalty shall be sufficient to cover the expense of feeding the panchayatdars (members of council), and leave a little over to be divided between the injured party and the headman. In this way, the headman gets paid for his services, and practically fixes his own remuneration.”

It is stated in the Manual of the Bellary district that “of the various Hindu castes in Bellary, the Bōyas (called in Canarese Bēdars, Byēdas, or Byādās) are far the strongest numerically. Many of the Poligars whom Sir Thomas Munro found in virtual possession of the country when it was added to the Company belonged to this caste, and their irregular levies, and also a large proportion of Haidar’s formidable force, were of the same breed. Harpanahalli was the seat of one of the most powerful Poligars in the district in the eighteenth century. The founder of the family was a Bōya taliāri, who, on the subversion of the Vijayanagar dynasty, seized on two small districts near Harpanahalli. The Bōyas are perhaps the only people in the district who still retain any aptitude for manly sports. They are now for the most part cultivators and herdsmen or are engaged under Government as constables, peons, village watchmen [184](taliāris), and so forth. Their community provides an instructive example of the growth of caste sub-divisions. Both the Telugu-speaking Bōyas and the Canarese-speaking Bēdars are split into the two main divisions of Ūru or village men, and Myāsa or grass-land men, and each of these divisions is again sub-divided into a number of exogamous Bedagas. Four of the best known of these sub-divisions are Yemmalavaru or buffalo-men; Mandalavaru or men of the herd; Pūlavaru or flower-men, and Mīnalavaru or fish-men. They are in no way totemistic.

Curiously enough, each Bedagu has its own particular god, to which its members pay special reverence. But these Bedagas bear the same names among both the Bōyas and the Bēdars, and also among both the Ūru and Myāsa divisions of both Bōyas and Bēdars. It thus seems clear that, at some distant period, all the Bōyas and all the Bēdars must have belonged to one homogeneous caste. At present, though Ūru Bōyas will marry with Ūru Bēdars and Myāsa Bōyas with Myāsa Bēdars, there is no intermarriage between Ūrus and Myāsas, whether they be Bōyas or Bēdars. Even if Ūrus and Myāsas dine together, they sit in different rows, each division by themselves. Again, the Ūrus (whether Bōyas or Bēdars) will eat chicken and drink alcohol, but the Myāsas will not touch a fowl or any form of strong drink, and are so strict in this last matter that they will not even sit on mats made of the leaf of the date-palm, the tree which in Bellary provides all the toddy. The Ūrus, moreover, celebrate their marriages with the ordinary ceremonial of the hālu-kamba or milk-post, and the surge, or bathing of the happy pair; the bride sits on a flour-grinding stone, and the bridegroom stands on a basket full of cholam (millet), and they call in Brāhmans to officiate. But the Myāsas have a simpler [185]ritual, which omits most of these points, and dispenses with the Brāhman. Other differences are that the Ūru women wear ravikkais or tight-fitting bodices, while the Myāsas tuck them under their waist-string. Both divisions eat beef, and both have a hereditary headman called the ejamān, and hereditary Dāsaris who act as their priests.”

In the Madras Census Report, 1901, it is stated that the two main divisions of Bōyas are called also Pedda (big) and Chinna (small) respectively, and, according to another account, the caste has four endogamous sections, Pedda, Chinna, Sadaru, and Myāsa. Sadaru is the name of a sub-division of Lingāyats, found mainly in the Bellary and Anantapur districts, where they are largely engaged in cultivation. Some Bēdars who live amidst those Lingāyats call themselves Sadaru. According to the Manual of the North Arcot district, the Bōyas are a “Telugu hunting caste, chiefly found above the ghāts. Many of the Poligars of that part of the country used to belong to the caste, and proved themselves so lawless that they were dispossessed. Now they are usually cultivators. They have several divisions, the chief of which are the Mulki Bōyas and the Pāla Bōyas, who cannot intermarry.” According to the Mysore Census Reports, 1891 and 1901, “the Bēdas have two distinct divisions, the Kannada and Telugu, and own some twenty sub-divisions, of which the following are the chief:—Hālu, Māchi or Myāsa, Nāyaka, Pallegar, Bārika, Kannaiyyanajāti, and Kirātaka. The Māchi or Myāsa Bēdas comprise a distinct sub-division, also called the Chunchus. They live mostly in hills, and outside inhabited places in temporary huts. Portions of their community had, it is alleged, been coerced into living in villages, with whose descendants the others [186]have kept up social intercourse.

They do not, however, eat fowl or pork, but partake of beef; and the Myāsa Bēdas are the only Hindu class among whom the rite of circumcision is performed,47 on boys of ten or twelve years of age. These customs, so characteristic of the Mussalmans, seem to have been imbibed when the members of this sub-caste were included in the hordes of Haidar Ali. Simultaneously with the circumcision, other rites, such as the pānchagavyam, the burning of the tongue with a nīm (Melia Azadirachta) stick, etc. (customs pre-eminently Brahmanical), are likewise practised prior to the youth being received into communion. Among their other peculiar customs, the exclusion from their ordinary dwellings of women in child-bed and in periodical sickness, may be noted.

The Myāsa Bēdas are said to scrupulously avoid liquor of every kind, and eat the flesh of only two kinds of birds, viz., gauja (grey partridge), and lavga (rock-bush quail).” Of circumcision among the Myāsa Bēdars it is noted, in the Gazetteer of the Bellary district, that they practise this rite round about Rayadrūg and Gudekōta. “These Myāsas seem quite proud of the custom, and scout with scorn the idea of marrying into any family in which it is not the rule. The rite is performed when a boy is seven or eight. A very small piece of the skin is cut off by a man of the caste, and the boy is then kept for eleven days in a separate hut, and touched by no one. His food is given him on a piece of stone. On the twelfth day he is bathed, given a new cloth, and brought back to the house, and his old cloth, and the stone on which his food was served, are thrown away. His relations in a body then take him to a tangēdu [187](Cassia auriculata) bush, to which are offered cocoanuts, flowers, and so forth, and which is worshipped by them and him. Girls on first attaining puberty are similarly kept for eleven days in a separate hut, and afterwards made to do worship to a tangēdu bush. This tree also receives reverence at funerals.”

The titles of the Bōyas are said to be Naidu or Nayudu, Naik, Dora, Dorabidda (children of chieftains), and Valmiki. They claim direct lineal descent from Valmiki, the author of the Rāmayana. At times of census in Mysore, some Bēdars have set themselves up as Valmiki Brāhmans. The origin of the Myāsa Bēdas is accounted for in the following story. A certain Bēdar woman had two sons, of whom the elder, after taking his food, went to work in the fields. The younger son, coming home, asked his mother to give him food, and she gave him only cholam (millet) and vegetables. While he was partaking thereof, he recognised the smell of meat, and was angry because his mother had given him none, and beat her to death. He then searched the house, and, on opening a pot from which the smell of meat emanated, found that it only contained the rotting fibre-yielding bark of some plant. Then, cursing his luck, he fled to the forest, where he remained, and became the forefather of the Myāsa Bēdars.

For the following note on the legendary origin of the Bēdars, I am indebted to Mr. Mainwaring. “Many stories are told of how they came into existence, each story bringing out the name which the particular group may be known by. Some call themselves Nishadulu, and claim to be the legitimate descendants of Nishadu. When the great Venudu, who was directly descended from Brahma, ruled over the universe, he was unable to procure a son and heir to the throne. When he died, his [188]death was regarded as an irreparable misfortune. In grief and doubt as to what was to be done, his body was preserved. The seven ruling planets, then sat in solemn conclave, and consulted together as to what they should do. Finally they agreed to create a being from the right thigh of the deceased Venudu, and they accordingly fashioned and gave life to Nishudu. But their work was not successful, for Nishudu turned out to be not only deformed in body, but repulsively ugly. It was accordingly agreed, at another meeting of the planets, that he was not a fit person to be placed on the throne. So they set to work again, and created a being from the right shoulder of Venudu.

Their second effort was crowned with success. They called their second creation Chakravati, and, as he gave general satisfaction, he was placed on the throne. This supersession naturally caused Nishudu, the first born, to be discontented, and he sought a lonely place. There he communed with the gods, begging of them the reason why they had created him, if he was not to rule. The gods explained to him that he could not now be put on the throne, since Chakravati had already been installed, but that he should be a ruler over the forests. In this capacity, Nishudu begot the Koravas, Chenchus, Yānādis, and Bōyas. The Bōyas were his legitimate children, while the others were all illegitimate. According to the legend narrated in the Valmiki Rāmayana, when king Vishwamitra quarrelled with the Rishi Vashista, the cow Kamadenu belonging to the latter, grew angry, and shook herself. From her body an army, which included Nishadulu, Turka (Muhammadans), and Yevannudu (Yerukalas) at once appeared.

“A myth related by the Bōyas in explanation of their name Valmikudu runs as follows. In former days, [189]a Brāhman, who lived as a highwayman, murdering and robbing all the travellers he came across, kept a Bōya female, and begot children by her. One day, when he went out to carry on his usual avocation, he met the seven Rishis, who were the incarnations of the seven planets. He ordered them to deliver their property, or risk their lives. The Rishis consented to give him all their property, which was little enough, but warned him that one day he would be called to account for his sinful deeds. The Brāhman, however, haughtily replied that he had a large family to maintain, and, as they lived on his plunder, they would have to share the punishment that was inflicted upon himself. The Rishis doubted this, and advised him to go and find out from his family if they were willing to suffer an equal punishment with him for his sins.

The Brāhman went to his house, and confessed his misdeeds to his wife, explaining that it was through them that he had been able to keep the family in luxury. He then told her of his meeting with the Rishis, and asked her if she would share his responsibility. His wife and children emphatically refused to be in any way responsible for his sins, which they declared were entirely his business. Being at his wit’s end, he returned to the Rishis, told them how unfortunate he was in his family affairs, and begged advice of them as to what he should do to be absolved from his sins. They told him that he should call upon the god Rāma for forgiveness. But, owing to his bad bringing up and his misspent youth, he was unable to utter the god’s name. So the Rishis taught him to say it backwards by syllables, thus:—ma ra, ma ra, ma ra, which, by rapid repetition a number of times, gradually grew into Rāma. When he was able to call on his god without difficulty, the Brāhman sat at the scene of his [190]graver sins, and did penance. White-ants came out of the ground, and gradually enveloped him in a heap. After he had been thus buried alive, he became himself a Rishi, and was known as Valmiki Rishi, valmiki meaning an ant-hill. As he had left children by the Bōya woman who lived with him during his prodigal days, the Bōyas claim to be descended from these children and call themselves Valmikudu.”

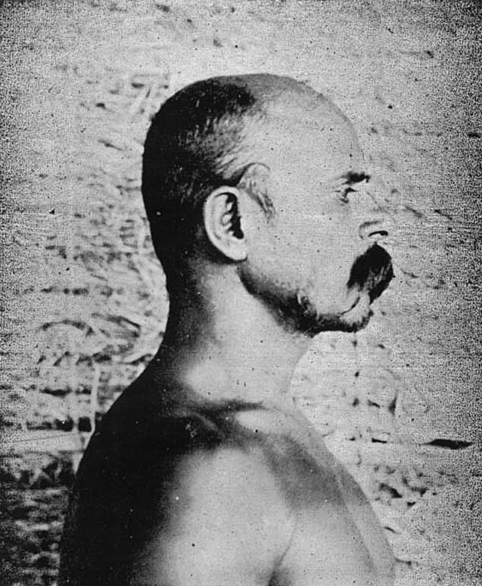

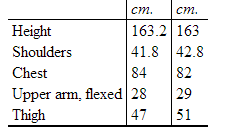

The Bēdars, whom I examined at Hospet in the Bellary district, used to go out on hunting expeditions, equipped with guns, deer or hog spears, nets like lawn-tennis nets used in drives for young deer or hares. Several men had cicatrices, as the result of encounters with wild boars during hunting expeditions, or when working in the sugar plantations. It is noted in the Bellary Gazetteer that “the only caste which goes in for manly sports seems to be the Bōyas, or Bēdars, as they are called in Canarese. They organise drives for pig, hunt bears in some parts in a fearless manner, and are regular attendants at the village gymnasium (garidi mane), a building without any ventilation often constructed partly underground, in which the ideal exercise consists in using dumbbells and clubs until a profuse perspiration follows. They get up wrestling matches, tie a band of straw round one leg, and challenge all and sundry to remove it, or back themselves to perform feats of strength, such as running up the steep Joladarāsi hill near Hospet with a bag of grain on their back.” At Hospet wrestling matches are held at a quiet spot outside the town, to witness which a crowd of many hundreds collect. The wrestlers, who performed before me, had the hair shaved clean behind so that the adversary could not seize them by the back hair, and the moustache was trimmed short for the same reason. [191]Two young wrestlers, whose measurements I place on record, were splendid specimens of youthful muscularity.

In the Gazetteer of Anantapur it is stated that the Telugu New Year’s day is the great occasion for driving pig, and the Bōyas are the chief organisers of the beats. All except children, the aged and infirm, join in them, and, since to have good sport is held to be the best of auguries for the coming year, the excitement aroused is almost ludicrous in its intensity. It runs so high that the parties from rival villages have been known to use their weapons upon one another, instead of upon the beasts of the chase. In an article entitled “Bōyas and bears”48 a European sportsman gives the following graphic description of a bear hunt. “We used to sleep out on the top of one of the hills on a moonlight night. On the top of every hill round, a Bōya was watching for the bears to come home at dawn, and frantic signals showed when one had been spotted. We hurried off to the place, to try and cut the bear off from his residence among the boulders, but the country was terribly rough, and the hills were covered with a peculiarly persistent wait-a-bit-thorn.

This, however, did not baulk the Bōyas. Telling me to wait outside the jumble of rocks, each man took off his turban, wound it round his left forearm, to act as a shield against attacks from the bear, lit a rude torch, grasped his long iron-headed spear, and [192]coolly walked into the inky blackness of the enemy’s stronghold, to turn him out for me to shoot at. I used to feel ashamed of the minor part assigned to me in the entertainment, and asked to be allowed to go inside with them. But this suggestion was always respectfully, but very firmly put aside. One could not see to shoot in such darkness, they explained, and, if one fired, smoke hung so long in the still air of the caves that the bear obtained an unpleasant advantage, and, finally, bullets fired at close quarters into naked rock were apt to splash or re-bound in an uncanny manner. So I had to wait outside until the bear appeared with a crowd of cheering and yelling Bōyas after him.” Of a certain cunning bear the same writer records that, unable to shake the Bōyas off, “he had at last taken refuge at the bottom of a sort of dark pit, ‘four men deep’ as the Bōyas put it, under a ledge of rock, where neither spears nor torches could reach him. Not to be beaten, three of the Bōyas at length clambered down after him, and unable otherwise to get him to budge from under the mass of rock beneath which he had squeezed himself, fired a cheap little nickel-plated revolver one of them had brought twice into his face. The bear then concluded that his refuge was after all an unhealthy spot, rushed out, knocking one of the three men against the rocks as he did so, with a force which badly barked one shoulder, clambered out of the pit, and was thereafter kept straight by the Bōyas until he got to the entrance of his residence, where I was waiting for him.”

Mr. Mainwaring writes that “the Bōyas are adepts at shikar (hunting). They use a bullock to stalk antelope, which they shoot with matchlocks. Some keep a tame buck, which they let loose in the vicinity of a herd of antelope, having previously fastened a net over [193]his horns. As soon as the tame animal approaches the herd, the leading buck will come forward to investigate the intruder. The tame buck does not run away, as he probably would if he had been brought up from infancy to respect the authority of the buck of the herd. A fight naturally ensues, and the exchange of a few butts finds them fastened together by the net. It is then only necessary for the shikāris to rush up, and finish the strife with a knife.”

Among other occupations, the Bōyas and Bēdars collect honey-combs, which, in some places, have to be gathered from crevices in overhanging rocks, which have to be skilfully manipulated from above or below.

The Bēdar men, whom I saw during the rainy season, wore a black woollen kambli (blanket) as a body-cloth, and it was also held over the head as a protection against the driving showers of the south-west monsoon. The same cloth further does duty as a basket for bringing back to the town heavy loads of grass. Some of the men wore a garment with the waist high up in the chest, something like an English rustic’s smock frock. Those who worked in the fields carried steel tweezers on a string round the loins, with which to remove bābūl (Acacia arabica) thorns, twigs of which tree are used as a protective hedge for fields under cultivation. As examples of charms worn by men the following may be cited:—

String tied round right upper arm with metal talisman box attached to it, to drive away devils. String round ankle for the same purpose.

Quarter-anna rolled up in cotton cloth, and worn on upper arm in performance of a vow.

A man, who had dislocated his shoulder when a lad, had been tattooed with a figure of Hanumān (the [194]monkey god) over the deltoid muscle to remove the pain.

Necklet of coral and ivory beads worn as a vow to the Goddess Huligamma, whose shrine is in Hyderabad.

Necklets of ivory beads and a gold disc with the Vishnupād (feet of Vishnu) engraved on it. Purchased from a religious mendicant to bring good luck.

Myāsa Bēdar women are said49 to be debarred from wearing toe-rings. Both Ūru and Myāsa women are tattooed on the face, and on the upper extremities with elaborate designs of cars, scorpions, centipedes, Sīta’s jade (plaited hair), Hanumān, parrots, etc. Men are branded by the priest of a Hanumān shrine on the shoulders with the emblem of the chank shell (Turbinella rapa) and chakram (wheel of the law) in the belief that it enables them to go to Swarga (heaven). When a Myāsa man is branded, he has to purchase a cylindrical basket called gopāla made by a special Mēdara woman, a bamboo stick, fan, and winnow. Female Bēdars who are branded become Basavis (dedicated prostitutes), and are dedicated to a male deity, and called Gandu Basaviōru (male Basavis).

They are thus dedicated when there happens to be no male child in a family; or, if a girl falls ill, a vow is made to the effect that, if she recovers, she shall become a Basavi. If a son is born to such a woman, he is affiliated with her father’s family. Some Bēdar women, whose house deities are goddesses instead of gods, are not branded, but a string with white bone beads strung on it, and a gold disc with two feet (Vishnupād) impressed on it, is tied round their neck by a Kuruba woman called Pattantha Ellamma (priestess [195]to Uligamma). Bēdar girls, whose house deities are females, when they are dedicated as Basavis, have in like manner a necklace, but with black beads, tied round the neck, and are called Hennu Basavis (female Basavis). For the ceremony of dedication to a female deity, the presence of the Mādiga goddess Mātangi is necessary. The Mādigas bring a bent iron rod with a cup at one end, and twigs of Vitex Negundo to represent the goddess, to whom goats are sacrificed. The iron rod is set up in front of the doorway, a wick and oil are placed in the cup, and the impromptu lamp is lighted. Various cooked articles of food are offered, and partaken of by the assembled Bēdars. Bēdar women sometimes live in concubinage with Muhammadans. And some Bēdars, at the time of the Mohurram festival, wear a thread across the chest like Muhammadans, and may not enter their houses till they have washed themselves.

According to the Mysore Census Report, 1901, the chief deity of the Bēdars is “Tirupati Venkatarāmanaswāmi worshipped locally under the name of Tirumaladēvaru, but offerings and sacrifices are also made to Māriamma. Their guru is known as Tirumalatatachārya, who is also a head of the Srīvaishnava Brāhmans. The Ūru Bōyas employ Brāhmans and Jangams as priests.” In addition to the deities mentioned, the Bēdars worship a variety of minor gods, such as Kanimiraya, Kanakarayan, Uligamma, Palaya, Poleramma, and others, to whom offerings of fruits and vegetables, and sacrifices of sheep and goats are made. The Dewān of Sandūr informs me that, in recent times, some Myāsa Bēdars have changed their faith, and are now Saivas, showing special reverence to Mahadēva. They were apparently converted by Jangams, but not to the fullest extent. The guru is the head of the Ujjani Lingayat matt (religious institution) [196]in the Kudligi tāluk of Bellary. They do not wear the lingam. In the Madras Census Report, 1901, the patron deity of the Bōyas is said to be Kanyā Dēvudu.

Concerning the religion of the Bōyas, Mr. Mainwaring writes as follows. “They worship both Siva and Vishnu, and also different gods in different localities. In the North Arcot district, they worship Tirupatiswāmi. In Kurnool, it is Kanyā Dēvudu. In Cuddapah and Anantapūr, it is Chendrugadu, and many, in Anantapūr, worship Akkamma, who is believed to be the spirit of the seven virgins. At Uravakonda, in the Anantapūr district, on the summit of an enormous rock, is a temple dedicated to Akkamma, in which the seven virgins are represented by seven small golden pots or vessels. Cocoanuts, rice, and dal (Cajanus indicus) form the offerings of the Bōyas. The women, on the occasion of the Nāgalasauthi or snake festival, worship the Nāgala swāmi by fasting, and pouring milk into the holes of ‘white-ant’ hills. By this, a double object is fulfilled. The ‘ant’ heap is a favourite dwelling of the nāga or cobra, and it was the burial-place of Vālmīki, so homage is paid to the two at the same time. Once a year, a festival is celebrated in honour of the deceased ancestors. This generally takes place about the end of November. The Bōyas make no use of Brāhmans for religious purposes.

They are only consulted as regards the auspicious hour at which to tie the tāli at a wedding. Though the Bōya finds little use for the Brāhman, there are times when the latter needs the services of the Bōya. The Bōya cannot be dispensed with, if a Brāhman wishes to perform Vontigadu, a ceremony by which he hopes to induce favourable auspices under which to celebrate a marriage. The story has it that Vontigadu was a destitute Bōya, who died from starvation. It is [197]possible that Brāhmans and Sūdras hope in some way to ameliorate the sufferings of the race to which Vontigadu belonged, by feeding sumptuously his modern representative on the occasion of performing the Vontigadu ceremony. On the morning of the day on which the ceremony, for which favourable auspices are required, is performed, a Bōya is invited to the house. He is given a present of gingelly (Sesamum) oil, wherewith to anoint himself. This done, he returns, carrying in his hand a dagger, on the point of which a lime has been stuck. He is directed to the cowshed, and there given a good meal. After finishing the meal, he steals from the shed, and dashes out of the house, uttering a piercing yell, and waving his dagger. He on no account looks behind him. The inmates of the house follow for some distance, throwing water wherever he has trodden. By this means, all possible evil omens for the coming ceremony are done away with.”

I gather50 that some Bōyas in the Bellary district “enjoy inām (rent free) lands for propitiating the village goddesses by a certain rite called bhūta bali. This takes place on the last day of the feast of the village goddess, and is intended to secure the prosperity of the village. The Bōya priest gets himself shaved at about midnight, sacrifices a sheep or a buffalo, mixes its blood with rice, and distributes the rice thus prepared in small balls throughout the limits of the village. When he starts out on this business, the whole village bolts its doors, as it is not considered auspicious to see him then. He returns early in the morning to the temple of the goddess from which he started, bathes, and receives new cloths from the villagers.” [198]

At Hospet the Bēdars have two buildings called chāvadis, built by subscription among members of their community, which they use as a meeting place, and whereat caste councils are held. At Sandūr the Ūru Bēdars submit their disputes to their guru, a Srīvaishnava Brāhman, for settlement. If a case ends in a verdict of guilty against an accused person, he is fined, and purified by the guru with thīrtham (holy water). In the absence of the guru, a caste headman, called Kattaintivadu, sends a Dāsari, who may or may not be a Bēdar, who holds office under the guru, to invite the castemen and the Samaya, who represents the guru in his absence, to attend a caste meeting. The Samayas are the pūjāris at Hanumān and other shrines, and perform the branding ceremony, called chakrānkitam. The Myāsa Bēdars have no guru, but, instead of him, pūjāris belonging to their own caste, who are in charge of the affairs of certain groups of families. Their caste messenger is called Dalavai.

The following are examples of exogamous septs among the Bōyas, recorded by Mr. Mainwaring:— • Mukkara, nose or ear ornament. • • Majjiga, butter-milk. • • Kukkala, dog. • • Pūla, flowers. • • Pandhi, pig. • • Chilakala, paroquet. • • Hastham, hand. • • Yelkamēti, good rat. • • Mīsāla, whiskers. • • Nemili, peacock. • • Pēgula, intestines. • • Mījam, seed. • • Uttarēni, Achyranthes aspera. • • Puchakayala, Citrullus Colocynthis. • • Gandhapodi, sandal powder. • • Pasula, cattle. • • Chinthakāyala, Tamarindus indica. • • Āvula, cow. • • Udumala, lizard (Varanus). • • Pulagam, cooked rice and dhal. • • Boggula, charcoal. • • Midathala, locust. • • Potta, abdomen. • • Ūtla, swing for holding pots. • • Rottala, bread. • • Chimpiri, rags. [199] • • Panchalingāla, five lingams. • • Gudisa, hut. • • Tōta, garden. • • Lanka, island. • • Bilpathri, Ægle Marmelos. • Kōdi-kandla, fowl’s eyes. • • Gādidhe-kandla, donkey’s eyes. • • Jōti, light. • • Nāmāla, the Vaishnavite nāmam. • • Nāgellu, plough. • • Ulligadda, onions. • • Jinkala, gazelle. • • Dandu, army. • • Kattelu, sticks or faggots. • • Mēkala, goat. • • Nakka, jackal. • • Chevvula, ear. • • Kōtala, fort. • • Chāpa, mat. • • Guntala, pond. • • Thappata, drum. • • Bellapu, jaggery. • • Chīmala, ants. • • Gennēru, Nerium odorum. • • Pichiga, sparrows. • • Uluvala, Dolichos biflorus. • • Geddam, beard. • • Eddula, bulls. • • Cheruku, sugar-cane. • • Pasupu, turmeric. • • Aggi, fire. • • Mirapakāya, Capsicum frutescens. • • Janjapu, sacred thread. • • Sankati, rāgi or millet pudding. • • Jerripōthu, centipede. • • Guvvala, pigeon. Many of these septs are common to the Bōyas and other classes, as shown by the following list:— • Āvula, cow—Korava. • • Boggula, charcoal—Dēvānga. • • Cheruku, sugar-cane—Jōgi, Oddē. • • Chevvula, ear—Golla. • • Chilakala, paroquet—Kāpu, Yānādi. • • Chīmala, ants—Tsākala. • • Chinthakāyala, tamarind fruit—Dēvānga. • • Dandu, army—Kāpu. • • Eddula, bulls—Kāpu. • • Gandhapodi, sandal powder—a sub-division of Balija. • • Geddam, beard—Padma Sālē. • • Gudisa, hut—Kāpu. • • Guvvala, pigeon—Mutrācha. • • Jinkala, gazelle—Padma Sālē. • • Kukkala, dog—Orugunta Kāpu. • Lanka, island—Kamma. • • Mēkala, goat—Chenchu, Golla, Kamma, Kāpu, Togata, Yānādi. [200] • • Midathala, locust—Mādiga. • • Nakkala, jackal—Dudala, Golla, Mutrācha. • • Nemili, peacock—Balija. • • Pichiga, sparrow—Dēvānga. • • Pandhi, pig—Asili, Gamalla. • • Pasula, cattle—Mādiga, Māla. • • Puchakāya, colocynth—Kōmati, Vīramushti. • • Pūla, flowers—Padma Sālē, Yerukala. • • Tōta, garden—Chenchu, Mīla, Mutrācha, Bonthuk Savara. • • Udumala, lizard—Kāpu, Tōttiyan, Yānādi. • • Ulligadda, onions—Korava. • • Uluvala, horse-gram—Jōgi. • • Utla, swing for holding pots—Padma Sālē. At Hospet, the preliminaries of a marriage among the Myāsa Bēdars are arranged by the parents of the parties concerned and the chief men of the kēri (street). On the wedding day, the bride and bridegroom sit on a raised platform, and five married men place rice stained with turmeric on the feet, knees, shoulders, and head of the bridegroom. This is done three times, and five married women then perform a similar ceremony on the bride. The bridegroom takes up the tāli, and, with the sanction of the assembled Bēdars, ties it on the bride’s neck. In some places it is handed to a Brāhman priest, who ties it instead of the bridegroom. The unanimous consent of those present is necessary before the tāli-tying is proceeded with. The marriage ceremony among the Ūru Bēdars is generally performed at the bride’s house, whither the bridegroom and his party proceed on the eve of the wedding. A feast, called thuppathūta or ghī (clarified butter) feast, is held, towards which the bridegroom’s parents contribute rice, cocoanuts, betel leaves and nuts, and make a present of five bodices (rāvike). At the conclusion of the feast, all assemble beneath the marriage pandal (booth), and [201]betel is distributed in a recognised order of precedence, commencing with the guru and the god. On the following morning four big pots, smeared with turmeric and chunam (lime) are placed in four corners, so as to have a square space (irāni square) between them.

Nine turns of cotton thread are wound round the pots. Within the square the bridegroom and two young girls seat themselves. Rice is thrown over them, and they are anointed. They and the bride are then washed by five women called bhūmathōru. The bridegroom and one of the girls are carried in procession to the temple, followed by the five women, one of whom carries a brass vessel with five betel leaves and a ball of sacred ashes (vibūthi) over its mouth, and another a woman’s cloth on a metal dish, while the remaining three women and the bridegroom’s parents throw rice. Cocoanuts and betel are offered to Hanumān, and lines are drawn on the face of the bridegroom with the sacred ashes. The party then return to the house. The lower half of a grinding mill is placed beneath the pandal, and a Brāhman priest invites the contracting couple to stand thereon. He then takes the tāli, and ties it on the bride’s neck, after it has been touched by the bridegroom. Towards evening the newly married couple sit inside the house, and close to them is placed a big brass vessel containing a mixture of cooked rice, jaggery (crude sugar) and curds, which is brought by the women already referred to. They give a small quantity thereof to the couple, and go away. Five Bēdar men come near the vessel after removing their head-dress, surround the vessel, and place their left hands thereon. With their right hands they shovel the food into their mouths, and bolt it with all possible despatch. This ceremony is called bhūma idothu, or special eating, and is in some [202]places performed by both men and women. All those present watch them eating, and, if any one chokes while devouring the food, or falls ill within a few months, it is believed to indicate that the bride has been guilty of irregular behaviour.

On the following day the contracting couple go through the streets, accompanied by Bēdars, the brass vessel and female cloth, and red powder is scattered broadcast. On the morning of the third and two following days, the newly married couple sit on a pestle, and are anointed after rice has been showered over them. The bride’s father presents his son-in-law with a turban, a silver ring, and a cloth. It is said that a man may marry two sisters, provided that he marries the elder before the younger.

The following variant of the marriage ceremonies among the Bōyas is given by Mr. Mainwaring. “When a Bōya has a son who should be settled in life, he nominally goes in search of a bride for him, though it has probably been known for a long time who the boy is to marry. However, the formality is gone through. The father of the boy, on arrival at the home of the future bride, explains to her father the object of his visit. They discuss each other’s families, and, if satisfied that a union would be beneficial to both families, the father of the girl asks his visitor to call again, on a day that is agreed to, with some of the village elders. On the appointed day, the father of the lad collects the elders of his village, and proceeds with them to the house of the bride-elect. He carries with him four moottus (sixteen seers) of rice, one seer of dhal (Cajanus indicus), two seers of ghī (clarified butter), some betel leaves and areca nuts, a seer of fried gram, two lumps of jaggery (molasses), five garlic bulbs, five dried dates, five pieces of turmeric, and a female jacket. In the [203]evening, the elders of both sides discuss the marriage, and, when it is agreed to, the purchase money has to be at once paid. The cost of a bride is always 101 madas, or Rs. 202. Towards this sum, sixteen rupees are counted out, and the total is arrived at by counting areca nuts. The remaining nuts, and articles which were brought by the party of the bridegroom, are then placed on a brass tray, and presented to the bride-elect, who is requested to take three handfuls of nuts and the same quantity of betel leaves. On some occasions, the betel leaves are omitted. Betel is then distributed to the assembled persons.

The provisions which were brought are next handed over to the parents of the girl, in addition to two rupees. These are to enable her father to provide himself with a sheet, as well as to give a feast to all those who are present at the betrothal. This is done on the following morning, when both parties breakfast together, and separate. The wedding is usually fixed for a day a fortnight or a month after the betrothal ceremony. The ceremony differs but slightly from that performed by various other castes. A purōhit is consulted as to the auspicious hour at which the tāli or bottu should be tied. This having been settled, the bridegroom goes, on the day fixed, to the bride’s village, or sometimes the bride goes to the village of the bridegroom. Supposing the bridegroom to be the visitor, the bride’s party carries in procession the provisions which are to form the meal for the bridegroom’s party, and this will be served on the first night. As the auspicious hour approaches, the bride’s party leave her in the house, and go and fetch the bridegroom, who is brought in procession to the house of the bride. On arrival, he is made to stand under the pandal which has been erected. A curtain is tied therein from north to [204]south. The bridegroom then stands on the east of the curtain, and faces west.

The bride is brought from the house, and placed on the west of the curtain, facing her future husband. The bridegroom then takes up the bottu, which is generally a black thread with a small gold bead upon it. He shows it to the assembled people, and asks permission to fasten it on the bride’s neck. The permission is accorded with acclamations. He then fastens the bottu on the bride’s neck, and she, in return, ties a thread from a black cumbly (blanket), on which a piece of turmeric has been threaded, round the right wrist of the bridegroom. After this, the bridegroom takes some seed, and places it in the bride’s hand. He then puts some pepper-corns with the seed, and forms his hands into a cup over those of the bride. Her father then pours milk into his hand, and the bridegroom, holding it, swears to be faithful to his wife until death. After he has taken the oath, he allows the milk to trickle through into the hands of the bride. She receives it, and lets it drop into a vessel placed on the ground between them. This is done three times, and the oath is repeated with each performance. Then the bride goes through the same ceremony, swearing on each occasion to be true to her husband until death. This done, both wipe their hands on some rice, which is placed close at hand on brass trays. In each of these trays there must be five seers of rice, five pieces of turmeric, five bulbs of garlic, a lump of jaggery, five areca nuts, and five dried dates. When their hands are dry, the bridegroom takes as much of the rice as he can in his hands, and pours it over the bride’s head. He does this three times, before submitting to a similar operation at the hands of the bride. Then each takes a tray, and upsets the contents over the other. At this [205]stage, the curtain is removed, and, the pair standing side by side, their cloths are knotted together.

The knot is called the knot of Brahma, and signifies that it is Brahma who has tied them together. They now walk out of the pandal, and make obeisance to the sun by bowing, and placing their hands together before their breasts in the reverential position of prayer. Returning to the pandal, they go to one corner of it, where five new and gaudily painted earthenware pots filled with water have been previously arranged. Into one of these pots, one of the females present drops a gold nose ornament, or a man drops a ring. The bride and bridegroom put their right hands into the pot, and search for the article. Whichever first finds it takes it out, and, showing it, declares that he or she has found it. This farce is repeated three times, and the couple then take their seats on a cumbly in the centre of the pandal, and await the preparation of the great feast which closes the ceremony. For this, two sheep are killed, and the friends and relations who have attended are given as much curry and rice as they can eat. Next morning, the couple go to the bridegroom’s village, or, if the wedding took place at his village, to that of the bride, and stay there three days before returning to the marriage pandal. Near the five water-pots already mentioned, some white-ant earth has been spread at the time of the wedding, and on this some paddy (unhusked rice) and dhal seeds have been scattered on the evening of the day on which the wedding commenced. By the time the couple return, these seeds have sprouted. A procession is formed, and the seedlings, being gathered up by the newly married couple, are carried to the village well, into which they are thrown. This ends the marriage ceremony. At their weddings, the Bōyas indulge in much music. Their dresses are [206]gaudy, and suitable to the occasion. The bridegroom, if he belongs to either of the superior gōtras, carries a dagger or sword placed in his cummerbund (loin-band). A song which is frequently sung at weddings is known as the song of the seven virgins. The presence of a Basavi at a wedding is looked on as a good omen for the bride, since a Basavi can never become a widow.”

In some places, a branch of Ficus religiosa or Ficus bengalensis is planted in front of the house as the marriage milk-post. If it withers, it is thrown away, but, if it takes root, it is reared. By some Bēdars a vessel is filled with milk, and into it a headman throws the nose ornament of a married woman, which is searched for by the bride and bridegroom three times. The milk is then poured into a pit, which is closed up. In the North Arcot Manual it is stated that the Bōya bride, “besides having a golden tāli tied to her neck, has an iron ring fastened to her wrist with black string, and the bridegroom has the same. Widows may not remarry or wear black bangles, but they wear silver ones.”

“Divorce,” Mr. Mainwaring writes, “is permitted. Grounds for divorce would be adultery and ill-treatment. The case would be decided by a panchāyat (council). A divorced woman is treated as a widow. The remarriage of widows is not permitted, but there is nothing to prevent a widow keeping house for a man, and begetting children by him. The couple would announce their intention of living together by giving a feast to the caste. If this formality was omitted, they would be regarded as outcastes till it was complied with. The offspring of such unions are considered illegitimate, and they are not taken or given in marriage to legitimate children. Here we come to further social distinctions. [207]Owing to promiscuous unions, the following classes spring into existence:— 1. Swajathee Sumpradayam. Pure Bōyas, the offspring of parents who have been properly married in the proper divisions and sub-divisions. 2. Koodakonna Sumpradayam. The offspring of a Bōya female, who is separated or divorced from her husband who is still alive, and who cohabits with another Bōya. 3. Vithunthu Sumpradayam. The offspring of a Bōya widow by a Bōya. 4. Arsumpradayam. The offspring of a Bōya man or woman, resulting from cohabitation with a member of some other caste. The Swajathee Sumpradayam should only marry among themselves. Koodakonna Sumpradayam and Vithunthu Sumpradayam may marry among themselves, or with each other. Both being considered illegitimate, they cannot marry Swajathee Sumpradayam, and would not marry Arsumpradayam, as these are not true Bōyas, and are nominally outcastes, who must marry among themselves.”

On the occasion of a death among the Ūru Bēdars of Hospet, the corpse is carried on a bier by Ūru Bēdars to the burial-ground, with a new cloth thrown over, and flowers strewn thereon. The sons of the deceased each place a quarter-anna in the mouth of the corpse, and pour water near the grave. After it has been laid therein, all the agnates throw earth into it, and it is filled in and covered over with a mound, on to the head end of which five quarter-anna pieces are thrown. The eldest son, or a near relation, takes up a pot filled with water, and stands at the head of the grave, facing west. A hole is made in the pot, and, after going thrice round the grave, he throws away the pot behind him, and goes home without looking back. This ceremony is called thelagolu, and, if a person dies without any heir, the [208]individual who performs it succeeds to such property as there may be. On the third day the mound is smoothed down, and three stones are placed over the head, abdomen, and legs of the corpse, and whitewashed. A woman brings some luxuries in the way of food, which are mixed up in a winnowing tray divided into three portions, and placed in the front of the stones for crows to partake of. Kites and other animals are driven away, if they attempt to steal the food. On the ninth day, the divasa (the day) ceremony is performed. At the spot where the deceased died is placed a decorated brass vessel representing the soul of the departed, with five betel leaves and a ball of sacred ashes over its mouth. Close to it a lamp is placed, and a sheep is killed. Two or three days afterwards, rice and vegetables are cooked. Those who have been branded carry their gods, represented by the cylindrical bamboo basket and stick already referred to, to a stream, wash them therein, and do worship. On their return home, the food is offered to their gods, and served first to the Dāsari, and then to the others, who must not eat till they have received permission from the Dāsari. When a Myāsa Bēdar, who has been branded, dies his basket and stick are thrown into the grave with the corpse.

In the Mysore Census Report, 1891, the Mysore Bēdars are said to cremate the dead, and on the following day to scatter the ashes on five tangēdu (Cassia auriculata) trees.

It is noted by Buchanan51 that the spirits of Baydaru men who die without having married become Vīrika (heroes), and to their memory have small temples and images erected, where offerings of cloth, rice, and the [209]like, are made to their names. If this be neglected, they appear in dreams, and threaten those who are forgetful of their duty. These temples consist of a heap or cairn of stones, in which the roof of a small cavity is supported by two or three flags; and the image is a rude shapeless stone, which is occasionally oiled, as in this country all other images are.”