Berar

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Berar

(otherwise known as the Hyderabad Assigned Districts). — A province, lying between 19° 35' and 21° 47 N. and 75° 59' and 79° 11’ E., which has been administered by the British Government on behalf of His Highness the Nizam of Hyderabad since 1853. It consists of a broad valley running east and west, between two tracts of hilly country, the Gawllgarh hills (the Melghat) on the north, and the Ajanta range (the Balaghat) on the south. The old name of the central valley was Payanghat ; and these three names — Melghat, Payanghat, and Balaghat — will be used to define the three natural divisions of the province. The area of Berar is 17,710 square miles.

The origin of the name Berar, or Warhad as it is spelt in MarathT, is not known. It may possibly be a corruption of Vidarbha, the name of a large kingdom in the Deccan, of which the modern Berar probably formed part in the age of the Mahabharata. The popular derivation from certain eponymous Warhadls, who accompanied Rukmin and Rukmini to AmraotI when the latter went to pay her vows at the temple of Amba Devi before her projected marriage to Sisupala, must be set aside as purely fanciful ; and Abul Fazl's derivation of the name from Wardha, the river, and tat, a ' bank,' is of no more value.

Berar is bounded on the north by the Satpuras and the Tapti, which separate it from the Central Provinces ; on the east, where again it adjoins the Central Provinces, by the Wardha ; along the greater part of its southern frontier, where it adjoins the Hyderabad State, by the Penganga ; while on the west an artificial line cutting across the broad valley from the Satpura Hills to the Ajanta range, and produced southwards over those hills, separates it from the Bombay Presidency and Hyderabad.

Physical aspects

The Gawilgarh hills attain their greatest height along the southern- most range, immediately overlooking the Payanghat, where the average elevation is about 3,400 feet, the highest summit being 3,989 feet. These hills decrease in height as Physical they stretch away towards the north, the average elevation of the range overlooking the Tapti being no more than 1,650 feet. The plateaux of the Balaghat do not attain the height of the hills of the Melghat, the elevation of Buldana, Basim, and Yeotmal being only 2,190 feet, 1,758 feet, and 1,583 feet, respectively. The general declination of the Balaghat table-land is from west to east, or in the direction of the Wardha river, that of the Gawllgarh hills being in the contrary direction.

The principal rivers of Berar are the Tapti, the Purna, 'the Wardha, and the Penganga. The Tapti runs from east to west and the Penganga from west to east, each following the general declination of the range from which it receives its principal affluents. The Wardha rises in the Satpuras and flows in a southerly direction, receiving the Penganga at the south-eastern corner of the province. The Puma, which is a tributary of the Tapti, drains the Payanghat, rising in the lower slopes of the Gawilgarh hills in Amraoti District, and running westward through the valley until it leaves the province at the northern- most corner of the Malkapur taluk. The Penganga rises in the hills near Deulghat in Buldana District, traverses that District in a south- easterly direction, and enters the Basim taluk near Wakad. From Yeoti eastwards it forms the southern boundary of Berar till it meets the Wardha at Jugad. Its prinicpal tributaries are the Pus, Arna, Aran, Waghari, KunT, and Vaidarbha, which rise in the Balaghat and flow to meet it in a south-easterly direction.

The only lake in Berar is the salt lake of Lonar in Buldana District. The scenery of the Payanghat is monotonous and uninteresting. The wide expanse of black cotton soil, slightly undulating, is broken by few trees except babuls and groves near villages. In the autumn the crops give it a fresh and green appearance ; but after the harvest the monotonous scene is unrelieved by verdure, shade, or water, and the landscape is desolate and depressing. The Balaghat is more varied and pleasing, though here also the country has a parched and arid appearance in the hot season. The ground is less level and the country generally is better wooded. It stretches in parts into downs and dales, or is broken up into flat-topped hills and deep ravines, while in its eastern section the country is still more sharply featured by a splitting up of the main hill range, which has caused that variety of low-lying plains, high plateaux, fertile bottoms, and rocky wastes found in Wiin District. The scenery of the Melghat is yet more picturesque, the most striking features of this tract being the abrupt scarps of trap rock near the summits of the hills, the densely wooded slopes, and the steep ravines. The undulating plateaux are rarely of great extent.

With the exception of the south-eastern corner, comprising a portion of Wun District, the whole of Berar is covered by the Deccan trap flows. In the south-eastern corner the trap has been removed by atmospheric agencies, exposing small patches of the underlying Lameta beds, and the great Godavari trough of Gondwana rocks, which are let down into very old unfossiliferous Purana strata, are regarded as pre- Cambrian in age, and are known in other parts of peninsular India as Vindhyans, Cuddapahs, &c. The Deccan trap is itself covered with

' From a note supplied by Mr. T. H. Holland, Director of the Geological Survey of India. alluvium in the valley of the Puma. The groups represented in Berar can be tabulated thus : —

Alluvium . . . Recent and pleistocene.

Deccan trap . . Upper Cretaceous or lower eocene.

Lameta . . Upper Cretaceous.

Gondwana . . Permo-carboniferous to Jurassic.

Purana . . . Pre-Cambrian.

The old rocks of the Purana group come to the surface on the south- eastern margin of the great cap of Deccan trap, occupying the border out to the main boundary of the Gondwana strata. They are covered by two small isolated patches of Deccan trap— outliers south-east of Kayar — and with some outliers of Gondwana beds in the Vaidarbha valley and farther west. In one or two small hills in this corner of the province the distinction between the Purana sandstones and the much later sandstones belonging to the Kamptee division of the Gondwana system is seen. Yanak hill (1,005 feet) is formed of Purana sandstones, and several bands of conglomerate occur containing pebbles of hematite, from which the iron ore formerly made at Yanak was obtained. Shales, slates, and limestones of the Purana group prevail to the west of the sandstone bed in Wun District, giving some magnificent sections in the Penganga and its tributaries.

The Gondwana rocks are especially worthy of notice, on account of their coal-measures. It has been estimated that about 2,100,000,000 tons of coal are available in Wun District. Direct evidence of the occurrence of coal has been obtained throughout 13 miles of country from Wun to Papur, and for 10 miles from Junara to Chincholl. It is estimated that there are 150,000,000 tons above the 500 feet level between Junara and ChincholT ; and the existence of thick coal has been proved in the Barakars which crop out near the Wardha river, in the south-eastern part of Wun District.

The Deccan trap, with which the greater part of Berar is covered, was erupted towards the end of Cretaceous times, the volcanic activity stretching on, probably, into the beginning of the Tertiary period. At the base, and stretching beyond the fringe, of the Deccan trap, there is often a fresh-water, or subaerial, formation, composed of clays, sand- stones, and limestones, representing the materials formed by weathering or actually deposited in water on the old continent over which the Deccan lava flows spread.

The hollow containing the lake of Lonar in Buldana District was probably caused by a violent gaseous explosion long after the eruption of the Deccan trap, and in comparatively recent times.

An interesting feature of the alluvial deposits in the valley of the Puma is the occurrence of salt in some of the beds at a little depth below the surface. Wells used formerly to be sunk on both sides of the river for the purpose of obtaining brine from the gravelly layers. The absence of fossils supports the idea that the salt is not derived from marine beds, but is in all probability due to the concentration of the salts ordinarily carried in underground water through the excessive surface evaporation which goes on in these dry areas for most of the year ^

2 The Melghat hills are forest-clad, the constituent vegetation being that characteristic of the Satpuras generally. The most plentiful species is Boswellia, accompanied by Cochlospermujn, Anogeissus latifo/ia, and Lagerstroemia pa^-viflora. Where the soil is deeper more valuable species, such as Tectona grandis, Dendrocalamus strictus^ and, more sparingly, Hardwickia hinata, are found occupying the valleys and ravines. Scattered throughout the forest occur Ougeinia dalbergioides, Adina cordifolia, Stephegyne parvifolia, Terminalia tomentosa^ Schrebera swietenioides, Eugoiia Jambolana, Bridelia retusa, Terminalia Chebitla ; some heavy creepers, such as Bauhinia Vahlii ; and species of Millettia, Combretum, Vifis, &c. On lighter gravelly soil, both in Northern and Southern Berar, forests with Hardwickia bifiafa are met with, Ptero- carpiis Marsiipium occurs near the edges of most of the high plateaux, with occasional trees of Dalbergia latifolia.

Where the soil in the Balaghat is thin, the slopes and plateaux are covered chiefly with Boswellia ; but in deeper soil Anogeissus latifo/ia, Diospyros ?nelanoxylon, and Terminalia tomentosa are the principal species. Along river banks considerable quantities of Terminalia Arjuna and Schleichera trijuga are sometimes met with. In the bottoms of the ravines are scattered clumps of Dendrocalamus sirictus. The hills are often bare and grass-clad, the most striking species being large Andropogons, Anthistirias, Iseilemas, &c. In level tracts, mangoes, tamarinds, mahuds, and p'lpals abound, with groves of Plwenix sylves- tris. Stretches of babul jungle are characteristic of the province. In cultivated ground the weed vegetation is that characteristic of the Deccan, and includes many small Compositae.

The principal wild animals are the tiger, the leopard, the hunting leopard, and the wild cat among Felidae. Deer and antelopes are represented by the sdmbar, the spotted deer, the barking-deer, the common Indian antelope, the nilgai, the four-horned antelope, and the chinkdra ; and Canidae by the Indian wolf, the Indian fox, the wild dog, and the jackal. The striped hyena, the wild hog, and the Indian black or sloth bear are of frequent occurrence, the last especially in the Melghat. Monkeys are represented by the langur

' Memoirs, Geological Survey of India,volRecords, Geological Su)-vey of hidia, vol. i, part iii ; General Neporf of (lie Geological Stir-'ey of India (1902-5).

'"' From a note supplied by Major D. I'rain, I. M.S., Director of the Botanical Survey. and the smaller red monkey, the latter being found in the Melghat only, while the former is common throughout the province.

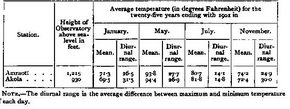

History

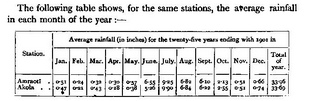

The climate differs very little from that of the Deccan generally, except that in the Payanghat the hot season is exceptionally severe. During April and May, and until the rains set in about the middle of June, the sun is very powerful, and there is by day severe heat, but without the scorching winds of Northern India. The nights are comparatively cool throughout, and during the rains the air is moist and fairly cool. The climate of the Balaghat is similar to that of the Payanghat, but the thermometer stands much lower than in the plains. On the higher plateaux of the Gawllgarh hills, the climate is always temperate, and at the sanitarium of Chikalda the heat is seldom so great as to be unpleasant. The following table shows the average tem- perature, at two representative stations, in January, May, July, and November : —

The rainfall is normally somewhat heavier in the Balaghat than in the Payanghat, and considerably heavier in the Melghat than in either.

Berar was anciently known as Vidarbha, under which name it is mentioned in the Mahabharata. In this epic the Raja of Vidarbha, Rukmin, is represented as an arrogant and presump- tuous prince, who vainly attempted to prevent the marriage of his sister RukminI to the demi-god Krishna, and who subsequently so disgusted the Pandavas by his pretensions that they declined his assistance in their quarrel with the Kauravas, leaving him to retire in dudgeon to his own dominions.

The next mention of Vidarbha is in connexion with the famous Oriental romance of Nala and Damayanti. Nala, Raja of Nishadha (Malwa), loved Damayanti, the daughter of Bhima, Raja of Vidarbha. It is unnecessary to pursue this story, which is mainly mythical, through its intricacies of detail ; but we learn from it that the kingdom of Vidarbha had for its capital a city of the same name, with which the city of Bidar in the Nizam's Dominions has been identified. If the identification be correct, and it is supported by legend as well as by etymology, we may conclude that the ancient kingdom was far more extensive than the modern province of Berar. Tradition says that its kings bore sway over the whole of the Deccan.

The authentic history of Berar commences with the Andhras or Satavahanas, of whose dominions it undoubtedly formed part. In the third century B.C., the Andhras occupied the deltas of the Godavari and Kistna, and were one of the tribes on the outer fringe of Asoka's empire. Soon after the death of that great ruler their territory was rapidly enlarged, and their sway reached Nasik. The twenty-third king, Vilivayakura II (a.d. 113-38), successfully warred against his neigh- bours, the western Satraps of Gujarat and Kathiawar, whose predecessors had encroached on the Andhra kingdom. A few years later, however, the Satraps were victorious and the Andhra rule appears to have come to an end about 236. The next rulers of the province of whom records have survived were the Rajas of the Vakataka dynasty, of whom there were ten. This dynasty was probably feudatory to the Vallabhis, but their chronology is very uncertain. The Abhiras or Ahirs, who succeeded the Vakatakas, are said to have reigned as independent sovereigns for only sixty-seven years ; but Ahir and Gaoli chieftains continued long afterwards to hold important forts in Berar and the neighbouring country, giving their names to their strongholds, as in the case of Gaoligarh in Khandesh, Asirgarh (Asa Ahir Garh) in the Central Provinces, and Gawilgarh in Berar. The Chalukyas next rose to power in the Deccan. Their dominions included Berar, and they reigned until 750, when they were overthrown by the Rashtrakutas, who ruled till 973, when the Chalukyas regained their ascendancy, which they retained, though not without vicissitudes, for two centuries. On the death, in 1189, of Somesvara IV, the last Raja of the restored Chalukya line, his dominions were divided between the Hoysala Ballalas of the south, whose capital was Dorasamudra or Dwaravati- pura', and the Yadavas of Deogiri, the modern Daulatabad, Berar naturally falling to the share of the latter. Raja Bhillama I, the founder of this dynasty, established himself at Deogiri in 11 88; and the Yadavas had reigned with some renown for rather more than a century, when, in

' Halebidi in Hassan District, Mvsore. the reign of Ramchandra, the sixth Raja, the Deccan was invaded by the Musalmans.

In 1294 Ala-ud-din, the nephew and son-in-law of Firoz Shah Khilji, Sultan of Delhi, invaded the Deccan by way of Chanderi and EUichpur. After defeating the Yadava Raja Ramchandra, styled Ramdeo by Muhammadan historians, at Deogiri, he was attacked by the Raja's son, whom also he defeated. He was then bought out of the country by a heavy ransom, which included the cession of the revenues of EUichpur, the district remaining under Hindu administration. On his return to Hindustan Ala-ud-din murdered his uncle at Kara and usurped the throne. Throughout his reign he dispatched successive expeditions into the Deccan, but in the confusion which followed his death in 1316 Harpal Deo of Deogiri rose in rebellion. He was defeated by Kutb- ud-din Mubarak Shah I in 13 17-8, and was flayed alive, his skin being nailed to one of the gates of Deogiri. His dominions were annexed to the Delhi empire, and thus Berar for the first time became a Muham- madan possession, which it has remained ever since. Berar gained considerably in importance during the reign of Muhammad bin Tughlak of Delhi, who in 1327 transferred the capital of his empire from Delhi to Daulatabad (Deogiri). In the latter years of this emperor's reign the Amirs of the Deccan rebelled, and in 1348 Hasan Gangu, Zafar Khan, was proclaimed Sultan of the Deccan under the title of Ala-ud-din Bahman Shah^

Ala-ud-din Bahman, shortly after he had ascended the throne, divided his kingdom into four provinces or taraft of which Berar, which included Mahur, Ramgarh, and Pathri, was the northernmost. During the next 130 years Berar furnished contingents in the innumerable wars waged by the Bahmani kings against the Rajas of Vijayanagar, Telin- gana, Orissa, and the Konkan, the Sultans of Gujarat, Malwa, and Khandesh, and the Gonds. It was overrun by Musalmans from the independent kingdoms on its northern frontier, by Gonds from Chanda, and by Hindus from Telingana. Ahmad Shah Wall, the ninth king of the Bahmani dynasty, found it necessary to recapture the forts of Mahur and Kalam in Eastern Berar, which had fallen into the hands of the infidels. In 1478 or 1479 Berar, which had hitherto been an impor- tant province with a separate army and governed by nobles of high rank and position, was divided into two governments, each of which was known by the name of its fortress capital, the northern being called Gawil and the southern Mahur. At the same time the powers of the provincial governors were much curtailed, all important forts being placed under the command of klladdrs, who were immediately sub- ordinate to the Sultan.

' Most historians have erred in respect of the title under which Bahman ascended the throne. His correct title is given as above in a contemporary inscription. These salutary reforms came too late to save the Bahmani dynasty from ruin ; and in the reign of the fourteenth Sultan, Mahmud Shah II, the principal iarafddrs, or provincial governors, proclaimed their independence. Imad-ul-mulk, who had formerly been governor of the whole of Berar and now held Gawil, proclaimed his independence in 1490 and soon annexed Mahur to his kingdom. He was by race a Kanarese Hindu, who had been made captive as a boy in one of the expeditions against Vijayanagar and brought up as a Musalman by the governor of Berar, to whose place he ultimately succeeded. Imad-ul- mulk died in 1504 and was succeeded by his son Ala-ud-din Imad Shah, who made Gawilgarh his capital and waged fruitless war against Amir Barid of Bidar and Burhan Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar. Ala-ud-din was succeeded on his death in 1529 by his son Darya Imad Shah, and he, after a peaceful and uneventful reign, by his son Burhan Imad Shah ( 1 560-1). This prince, shortly after his accession, was imprisoned in Narnala by his minister, Tufal Khan, who declared himself independent.

In 1572 Murtaza Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar invaded Berar with the avowed intention of releasing Burhan from confinement. Tufal Khan, his son Shams-ul-mulk who had surrendered Gawilgarh, and Burhan were captured shortly afterwards, and were imprisoned and put to death. Thus ended the rule of the Imadshahi dynasty in Berar, after a duration of eighty-five years.

The Ahmadnagar dynasty was not long destined to hold possession of the prize. At home it could do nothing to quell civil broils and allay dangerous feuds. Even when the famous Chand Bibi became queen- regent there was no chance of upholding a tottering state. In 1595 Sultan Murad, the fourth son of the emperor Akbar, besieged Ahmad- nagar, but raised the siege, early in 1596, on receiving the formal cession of Berar.

In those times the Deccan swarmed with adventurers from every nation in Asia and even from the African coast of the Indian Ocean. These men and their descendants settled in the towns, and their chiefs occupied most of the high military and civil offices ; but the Musalman rulers of the Deccan did nothing to disturb the routine of ordinary revenue collections and the administration of the internal affairs of villages and parganas, so that the old Hindu organization, with its hereditary /ar^'-a^a and village officials, the relic, perhaps, of a civiliza- tion older still, was allowed to remain, recognized by the conquerors as a more convenient administrative machine than any which they could devise. There are now in Berar several Muhammadan families of deshmukhs (former pargana officials) ; but they are all believed, and for the most part admit themselves, to be descendants of Hindus who in the reign of Aurangzeb accepted Islam in preference to relinquishing their hereditary offices. They may be distinguished from other Musal- mans by their antipathy to beef, and frequently by a partiality for Hindu names, while in one case there are in neighbouring /(7r^rt';/rt'i" two families of deshmukhs, one Musalman and the other Hindu, acknow- ledged cousins, both of them claiming to be Rajputs by caste. Of the principal Maratha families enumerated by Grant Duff as holding good positions under the Bahmani monarchy, that of Jadon Rao is the only one belonging to Berar. In lineage and historical repute it yields to none, even if its claim to descent from the Yadava Rajas of Deogiri be discredited ; and the line is not yet extinct.

Sultan Murad, after the annexation of Berar to the Mughal empire, founded a town about 6 miles from Balapur, which he named Shahpur, making it his residence ; and the newly won province was divided among the Mughal nobles. After Murad's death in 1598 Akbar formed the design of conquering the whole of the Deccan. Ahmadnagar was besieged and captured ; and Daniyal, the emperor's fifth son, was appointed governor of Ahmadnagar, Khandesh, and Berar. He died in 1605, in the same year as his father, Akbar. For the greater part of the reign of Jahanglr, Ak bar's son and successor, Berar was in the possession of Malik Ambar, the Abyssinian (died 1626), who repre- sented the independence of the moribund dynasty of Ahmadnagar, and to whose military genius and administrative capacity a generous tribute is paid in the TTizak-i-/akd>igJrI, the official record of Jahangir's reign.

In the first year of Shah Jahan, Berar passed once more under the Mughal sway. In 1636 the whole of that part of the Deccan which was in the possession of the Mughals was divided into four SFibahs, or provinces, one of which was Berar, with EUichpur as its capital and Gawilgarh as its principal fortress. Aurangzeb, Shah Jahan's third son, was appointed viceroy of these four Subahs. After Aurangzeb deposed his father, the resources of Berar were taxed to the utmost by his cam- paigns in Bijapur, Golconda, and Southern India, and at the same time the province was the prey of Maratha marauders. In 1680 it was over- run by Sambhajl, the son of SivajT; and in 1698 Rajaram, the half- brother and successor of Sambhajl, aided by Bakht Buland, the Gond Raja of Deogarh, who had embraced Islam in order to obtain Aurangzeb's support, again devastated the province.

In 1 718 Abdullah and Husain All Khan, the Saiyid ministers of the emperor Farrukh Siyar, formally recognized the claim of the Marathas, who periodically overran Berar, to chaufh, or blackmail, to the extent of one-quarter of the revenue, and also permitted them to levy from the ryots the contribution known as sardes/mnikki, which seems to have been a royalty on appointments to or recognitions of the old Hindu office of deshmukh, and amounted to 10 per cent, of the revenue collections.

A year later Muhammad Shah ascended the throne of Delhi, but the government was still in the hands of the two Saiyids. Chin Killj Khan, afterwards known as Asaf Jah, who had distinguished himself in the later wars of Aurangzeb, had been appointed viceroy of the Deccan under the tide of Nizam-ul-mulk, but was opposed by the court party at Delhi, who sent secret instructions to Mubariz Khan, governor of Khan- desh, urging him to withstand Asaf Jah by force of arms. In 1724 a battle was fought at Shakarkhelda in Buldana District, in which Mubariz Khan was utterly defeated.

This battle established the virtual independence of Asaf Jah, the founder of the line of the Nizams of Hyderabad, who, to celebrate his victory, renamed the scene of it Fathkhelda, or 'the village of victory'; and from that day Berar has always been nominally subject to the Nizam. The Bhonsla Rajas of Nagpur posted their officers all over the province ; they occupied it with their troops ; they collected more than half the revenue, and they fought among themselves for the right to collect ; but the Nizam con- stantly maintained his title as de jure ruler of the country, with the exception of Mehkar and some parganas to the south, which were ceded to the Peshwa in 1760 after the battle of Udgir, and Umarkhed and o\h&c parganas ceded in 1795 ^^^^^ ^^ battle of Kardla. This struggle between Mughal and Maratha for supremacy in Berar commenced in 1737 between Asaf Jah and Raghuji Bhonsla. It ended in 1803, when, after the defeat of the Maratha confederacy at Assaye and Argaon, and the capture of GawTlgarh by General Arthur Wellesley, the Bhonsla Raja signed a treaty by which he resigned all claim to territory and revenue west of the Wardha, Gawilgarh and Narnala, with a small tract of land afterwards exchanged, remaining in his possession.

The injury caused to Berar by the wars of the eighteenth century must have been wide and deep. Described in the Ain-i-Akbari as highly cultivated and in parts populous, supposed by M. de Thevenot in 1667 to be one of the wealthiest portions of the Mughal empire, it fell on evil days before the close of the seventeenth century. Cultivation fell off just when the finances were strained by the long wars; the local revenue officers rebelled ; the army became mutinous ; and the Marathas easily plundered a weak province when they had severed its sinews by cutting off its trade. Wherever the Mughals appointed a collector the Marathas appointed another, and both claimed the revenue, while foragers from each side exacted forced contributions, so that the harassed cultivator often threw up his land and helped to plunder his neighbour. The Marathas by these means succeeded in fixing their hold on the province ; but its resources were ruined, and its people were seriously demoralized by a regime of barefaced plunder and fleecing without the semblance of principle or stability.

By the partition treaty of Hyderabad (1804) the Berar territories ceded by the Bhonsla Raja were made over to the Nizam. Some tracts about Sindkhed and Jalna were also restored by Sindhia to the Hyderabad State.

The Treaty of Deogaon had put a stop to actual warfare in Berar, but the people continued to suffer intermittently from the inroads of Pin- daris, and incessantly from misgovernment ; for the province had been restored to the Nizam just at the time when confusion in his territories was at its worst. ' The Nizam's territories,' wrote General Wellesley in January, 1804, 'are one complete chaos from the Godavari to Hyder- abad ' ; and again, ' Sindkhed is a nest of thieves ; the situation of this country is shocking ; the people are starving in hundreds, and there is no government to afford the slightest relief.'

After the conclusion of the war of 181 7-8, which did not seriously affect the tranquillity of Berar, a treaty was made in 1822 which fixed the Wardha river as the eastern frontier of the province, the Melghat and the subjacent districts in the plains being restored to Hyderabad in exchange for the districts east of the Wardha and those held by the Peshwa. The treaty also extinguished the Maratha claim to chauth.

Between 1803 and 1820 the revenue of Berar had declined by one- half owing to the raids of Pindaris and Bhils, while the administration was most wasteful, no less than 26,000 troops being quartered on the province. General A\'ellesley had advised in 1804 that the local gover- nor should be compelled to reform his military establishment, foretelling the aggravation of civil disorder by the sudden cessation of arms. The disbanded troops were too strong for the weak police, while the spread of British dominion established order all around, and drove all the brigands of India within the limits of Native States. So Berar was har- ried from time to time by bands of men under leaders who on various pretexts, but always with the real object of plunder, set up the standard of rebellion. Sometimes the British irregular forces had to take the field against them, as, for instance, in 1849, when a man styling himself Appa Sahib Bhonsla, ^.v-Raja of Nagpur, was with difficulty captured. Throughout these troubles the Hindu deshmukhs and other pargafia officials were openly disloyal to the Nizam's government, doing their best to thwart his commanders and abetting the pretenders. The last fight against open rebels took place at Chichamba, near Risod, in 1859.

After the old war-time came the 'cankers of a calm world,' for then began the palmy days of the great farmers-general at Hyderabad. Messrs. Palmer & Co. overshadowed the Government and very nearly proved too strong for Sir Charles Metcalfe when he laid the axe to the root of their power. The firm had made large loans at 24 per cent, for the numerous cavalry maintained in Berar. Then Puran Mai, a great money-lender of Hyderabad, got most of Berar in farm; but in 1839 he was turned out, under pressure from the Resident, in favour of Messrs. PestonjI & Co. These were enterprising Parsi merchants, who in 1825-6 made the first considerable exportation of cotton from Berar to Bombay. They gave Hberal advances to cotton-growers, set up presses at Khamgaon and other places, and took up, generally, the export of produce from the Nizam's country. In 1841 Chandu Lai, the Hyderabad minister, gave them large assignments of revenue in Berar in repayment of loans to the State; but in 1843 the minister resigned, having conducted the State to the verge of bankruptcy, and PestonjI was subsequently forced to give up his Berar districts.

All these proceedings damaged the State's credit, as Chandu Lai's financing had hampered its revenue; and in 1843 and several succeed- ing years the pay of the Irregular Force maintained under the treaty of 1800 had to be advanced by the British Government. In 1850 it had fallen again into heavy arrears, and in 1853 the debt due to the Bri- tish Government on account of this pay and other unsatisfied claims amounted to 45 lakhs. The bankruptcy of the State disorganized the administration, and the non-payment of the troops continued to be a serious political evil. Accordingly, in 1853, a new treaty was concluded with the Nizam, under which the Hyderabad Contingent was to be maintained by the British Government, while for the payment of this force, and in satisfaction of the other claims, districts yielding a gross revenue of 50 lakhs were assigned to the Company. The Berar dis- tricts 'assigned' by this treaty are now popularly understood to form the province of Berar, which was administered on behalf of the Govern- ment of India by the Resident at Hyderabad, though they coincide in extent neither with the Berar of the Nizams nor with the imperial Subah.

The territory made over under this treaty comprised, besides Berar, the districts of Dharaseo and the Raichur Doab. It was agreed that ac- counts should be annually rendered to the Nizam, and that any surplus revenue should be paid to him. His Highness was released from the obligation of furnishing a large force in time of war, and the Con- tingent ceased to be a part of his army, and became an auxiliary force kept up by the British Government for his use.

The provisions of the treaty of 1853, which required the submission of annual accounts to the Nizam, were, however^ productive of much inconvenience and embarrassing discussions. Difficulties had also arisen regarding the levy of customs duties under the commercial treaty of 1802. To remove these difficulties, and at the same time to reward the Nizam for his services in 1857, a new treaty was concluded in i860, by which a debt of 50 lakhs due from him was cancelled ; and he also received the territory of Surapur, which had been confiscated for the rebellion of the Raja, and the districts of Dharaseo and Raichur were restored to him. On the other hand, he ceded certain districts on the left bank of the Godavari, traffic on which river was to be free from all duties, and agreed that Berar should be held in trust for the purposes specified in the treaty of 1853.

The history of Berar from 1853 to 1902 is marked by no important political events other than the changes made by the treaty of i860. Its smooth course was scarcely rufitled even by the cyclone of 1857. AV^hat- ever secret elements of disturbance may have been at work, the country remained calm, measuring its behaviour not by Delhi, but by Hyderabad. In 1858 Tantia Topi got into the Satpura Hills, and tried to breakaway to the south that he might stir up the Deccan, but he was headed at all outlets and never reached the Berar valley.

The management of Berar by the Nizam's officials had been worse than the contemporary administration of the adjoining Nagpur territory, which was, during a long minority, under British regency, and was subsequently well governed until it lapsed. There had consequently been wholesale emigration from Eastern Berar to the Districts beyond the Wardha. When Berar came under British management the emigrants, with the usual attachment of Indian cultivators to their patrimony, the value of which had in this case been enhanced by much of it having remained fallow for some time, returned in thousands to Berar. This was only one mode out of several, which it would be tedious to detail, whereby cultivation was restored and augmented. Then supervened the American Civil War. The cultivation of cotton received an extraordinary stimulus, the cultivators importing their supply of food-grains so that all available land might be devoted to the cultivation of the more profitable crop. Cotton requires much manual toil in weeding, picking, ginning, packing and the like, and the increase in the area under it created a great demand for rural labour, which operated to raise the standard of wages. A great export of cotton to Bombay was soon established ; and as the importation of foreign produce was far from proportionate, much of the return consisted of cash and bullion, so that prices rose and the labouring and producing classes were rapidly enriched. At the same time a line of railway was being laid across the province, causing the employment of all labour, skilled and unskilled, that could be got on the spot, and also in- troducing a large foreign element. The people became prosperous and contented, and progress in all departments was vast and rapid.

The Census Report of 188 1 showed material advance. The cultivated area had increased by 50 per cent, and the land revenue by 42 per cent, since 1867. But although Berar escaped the widespread famine of 1876-8, the poorer classes undoubtedly suffered much hardship at that time, and cattle died by thousands for want of fodder. The next ten years were, on the whole, prosperous, though cholera, which generally appeared in an intense form every other year, caused great mortality.

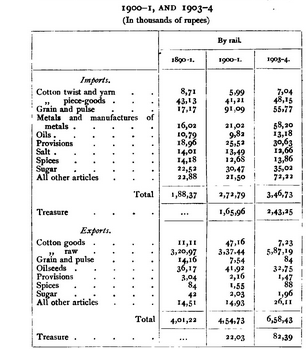

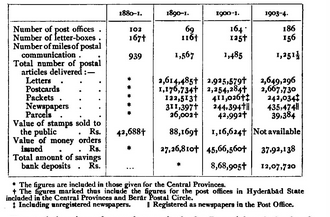

There was, however, an increase in trade, cultivation, and manufactures, and the population rose by 8 per cent. The ten years preceding 1901 were not, owing to natural causes, marked by a general increase in prosperity, but the province displayed considerable stability and power of resistance. There was but one year in the decade, 1898, which could be described as very favourable, and even then the 7-abi crops partially failed. The other nine years were marked by unseasonable or deficient rainfall, poor harvests, sickness, and high mortality, culminating in 1899 and 1900, when famine was sore in the land. The population decreased by 5 per cent, during the decade. But, notwithstanding all this, other statistics show steady progress and development. Cultivation has extended ; the value of the import and export trade has increased ; and the number of steam factories has risen by 84 per cent.

It had gradually become apparent since i860 that the maintenance of the Hyderabad Contingent on its old footing as a separate force was inexpedient and unnecessary, and also that the administration of so small a province as Berar as a separate unit was very costly. In 1902, therefore, a fresh agreement was entered into with the Nizam. This agreement reaffirmed His Highness's rights over Berar, which, instead of being indefinitely ' assigned ' to the Government of India, was leased in perpetuity on an annual rental of 25 lakhs ; and authorized the Government of India to administer the province in such manner as it might deem desirable, as well as to redistribute, reduce, reorganize, and control the Hyderabad Contingent, due provision being made, as stipu- lated in the treaty of 1853, for the protection of His Highness's dominions. In pursuance of this agreement the Contingent ceased, in March, 1903, to be a separate force, and was reorganized and redistributed as an integral part of the Indian army.

In October, 1903, Berar was transferred to the administration of the Chief Commissioner of the Central Provinces. For the present the rental paid to the Nizam is charged with an annual debit of 10 lakhs, towards the repayment of loans made by the Government of India for famine expenditure in Berar and for famine and other expenditure in the Hyderabad State. When these loans have been repaid, the Nizam will receive the full rent of 25 lakhs. The advantages secured to him by the new agreement are manifest, His rights over Berar have been reaffirmed, and he will receive 25 lakhs per annum, compared with a sum of between 8 and 9 lakhs which was the average surplus paid to him under the former treaties.

The principal remains of archaeological or historical interest in Berar are the small cave monastery and the shrine of Shaikh Baba at Patur ; the chhatri of Raja Jai Singh and the fort at Balapur ; various massive stone temples attributed to the era of the Yadava Rajas of Deogiri, and locally known as Hemadpanti temples, in the Chalukyan style ; some

Jain shrines, particularly that at Sirpur ; the hill forts of GawIlgarh and Narnala; and the mosques at Fathkhelda and Rohankhed. The principal Hemadpanti temples are those at Lonar, Mehkar, Bars! Takli, and Pusad, but many others are scattered throughout the province.

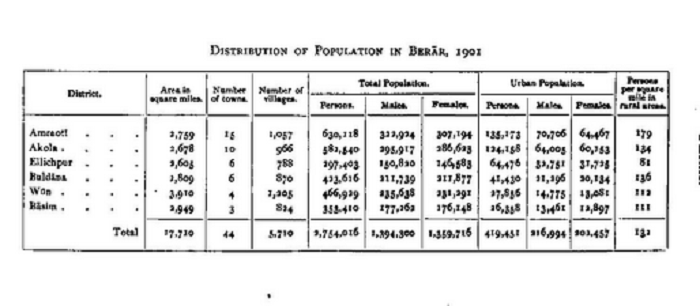

Population

The population of Berar in 1901 was 2,754,016, or 155 persons per square mile. The distribution varies in accordance with the natural advantages of the three divisions of the province. Thus the density in the twelve taluks of the Payan- ghat varies from 150 to 311 persons per square mile, and that of the nine taluks of the Balaghat from 85 to 150, while the population of the Melghat is very sparse, the density being no more than 22 persons per square mile.

The table on the next page shows the population of the six Districts of the province in 1901. In 1905 the six Districts were rearranged; Ellichpur, Wun, and Basim have been abolished, and a new District of Yeotmal has been formed. The present distribution of area and population will be found in the several District articles.

The term ' village ' denotes in Berar the area demarcated for revenue purposes as a inauza or kasba, mazras or hamlets being reckoned for census purposes as part of the principal village. The term ' town ' includes every municipality and civil station and villages with a popu- lation of 5,000 or more. The villages are agricultural communities, each with its hereditary officers and servants, the former paid by a per- centage on collections and the latter by customary dues in kind. The gaothiln, or village site, on which the houses are collected together, is not surrounded by a wall ; but each village has its garhl, or fort, usually of earth, in which the village officers possess hereditary rights, but which was formerly used as a place of refuge by the whole community in troublous times.

The first Census of Berar, which was taken in 1867, disclosed a total population of 2,227,654. By 1881 this had increased to 2,672,673, and by 1891 to 2,897,491. The Census of 1901 showed a decrease to 2,754,016, or by 4-9 per cent., due to the famines of 1896-7 and 1899-1900, and to abnormally high mortality from disease in the years 1894-7 and 1900. One feature of the decade was the gravitation of an unusually large proportion of the. people towards the towns, the percentage of urban population to the whole being 15-2 in 1901, compared with i2'5 in 1881.

The deductions to be drawn from the age statistics in the Report on the Census of 190 1 may be thus summarized : infant mortality is greatest between the ages of one and two ; the mortality among children born in the first half of the decade ending 1901 was considerably less than that among children born in the second half, the difference being attributable

to the harder conditions of hfe in the second quinquennium ; there is a general tendency to understate the age of marriageable girls ; the last quinquennial period of life exhibited in the tables (55-60) is the most fatal ; and famine and disease have principally affected the youngest and the oldest of the females, and the youngest and those over thirty among the males.

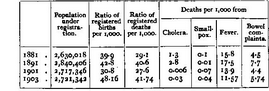

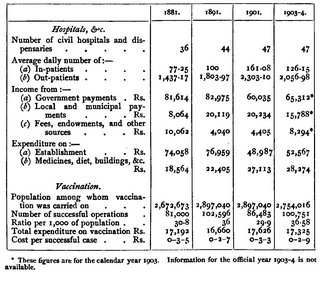

The registration of births and deaths is carried out with greater accuracy in Berar than in most of the Provinces of British India proper, though the entire population is not under registration. The following table shows the birth and death-rates and the principal fatal diseases in 1881, 1891, 1901, and 1903: —

The variation between the birth and death-rates in the different Districts is not constant, and it can hardly be said that any one District is conspicuously more healthy or unhealthy than the rest. The birth- rate seems to be usually highest in Buldana. Throughout the early part of the decade ending 1901 birth and death-rates were consistently lower in Wun than elsewhere ; but this was probably due to defective registration, as the District is no longer exceptional in this respect. Both birth and death-rates were seriously affected by the famine of 1899-1900.

The most prevalent disease is fever, the deaths from which about equal in number those from all other causes. Bowel complaints are the next most frequent cause of death. Plague did not appear in Berar till 1903, and the Administration, in coping with it, profited by the experience gained in other Provinces. Evacuation and disinfection were the principal measures adopted.

Males outnumber females by 34,584. It has been ob.served since 1 88 1 that male births outnumber female, but that throughout the first decade of life females outnumber males. It may therefore be inferred, allowing for the habit of understating the age of marriageable daughters, that female infanticide is unknown in Berar. The ratio of females to males is less in towns than in villages, for the towns contain male workers who leave their families behind them. The same circum- stances affect the population of certain taluks. The greater the commercial element in a tdluk^ the less is the proportion of females to males.

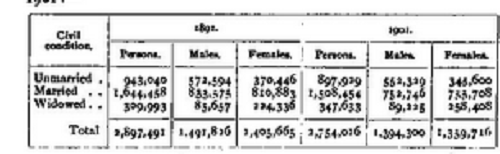

The following table gives statistics of civil condition for 1891 and 1901 : —

Of the male population 40, 54, and 6 per cent., and of the female

25, 56, and 19 per cent, are single, married, and widowed respectively.

Married males and females are fairly evenly balanced, so that it is

evident that polygamy, though permitted by all the religions the

followers of which are numerically important, is but sparingly prac-

tised. No relics of polyandry survive. Widow remarriage is pro-

hibited, not only among the higher castes of Hindus, but also among

the well-to-do in inferior castes, such as members of deshvuikh families

among Kunbls. It is allowed and extensively practised among most

of the agricultural castes, and is known as pat or mohtur, in contra-

distinction to /agna, a word which is applied only to the marriage of a

virgin bride. Among some tribes, Banjaras and Gonds for example,

the levirate prevails, i. e. it is the duty of a man to take to wife the widow

of his deceased elder brother, though to marry a younger brother's

widow would be regarded as incestuous. Child marriage is the

general rule among the higher castes of Hindus. Animists usually

defer marriage until after the attainment of puberty, and allow greater

freedom of choice to the parties concerned.

The joint-family system is the rule among Hindus in Berar. Ignorant Musalmans too will assert in civil suits that they are members of an undivided family when they believe that the assertion may suit their interests.

Marathi is spoken by nearly 80 per cent, of the population. The Musalmans, 212,000 in number, speak a corrupt dialect of Urdu, popularly known as Musalmani ; other dialects of Western Hindi, returned as Hindi and Hindustani, are spoken by immigrants from the United and Central Provinces. The Marwari dialect of RajasthanI was spoken in 1901 by 41,521 traders and bankers from Marwar. Gipsy dialects, of which Banjari or Labhanl is the most important, were spoken by 68,879 persons. Of Dravidian languages Gondi and its dialects, of which the principal is Kolami, were spoken by 83,217 persons, and Telugu by 85,431, mostly dwellers in the south of Wun

District on the banks of the Penganga. The only important Munda language is Korku, spoken by the Korkus in the Melghat and its neighbourhood. Nihali is a moribund language of uncertain affinities, returned as the mother-tongue of 91 Nihals, who, however, probably speak Korku, defining it as Nihali. English was returned as the mother tongue of 653 persons.

In this small province nearly four hundred castes and tribes are represented. The three chief groups coincide generally with the main religious divisions, Hindu, Muhammadan, and Animistic. Musalmans call for little notice in this connexion. Many of them are descendants of converted Hindus. Shaikhs number 131,000; Pathans, 52,000; Saiyids, 19,000; and Mughals, 4,000.

The Kunbis, the great cultivating caste of the Provinces, are the most important of the Hindu castes. They number 791,000, and pre- dominate in every taluk except the Melghat. Very similar to them in all respects are the Mails, numbering 193,000. The Kunbi is usually of medium height, dark-skinned from exposure, and wiry. As a cultivator he is moderately industrious, but devoid of enterprise and intelligent energy. Next to the Kunbis the Mahars, numbering 351,000, are the most numerous caste. The Mahar occupies an important, if humble, place in the village system of the Deccan. Socially he is regarded as an unclean outcaste whose touch is pollution. Similar to the Mahars, but even more unclean, are the Mangs, who number 49,000. Other numerically important castes are : Telis (77,000), Dhangars (75,000), Brahmans (73,000), Banjaras (60,000), Warns (41,000), and Rajputs (36,000). The indigenous Rajputs are not favourable specimens of their class, and it is doubtful whether their claim to pure descent would be admitted in Rajasthan.

The two principal aboriginal tribes are the Gonds and the Korkus, the former ordinary Dravidian and the latter Munda. The Gonds number 69,000, or, if the cognate Kolams and Parahans be included, 96,000. They are very dark and usually slight and undersized, though exceptions are found among the division known as Raj Gonds. The Korkus number 26,000, and have their home in the north of the province among the GawTlgarh hills. Their physique is superior to that of the Gonds, and they are well-built and muscular, but their personal appearance is not pleasing. They are distinguished princi- pally by their small eyes, large mouths, flat noses, and large and prominent ears.

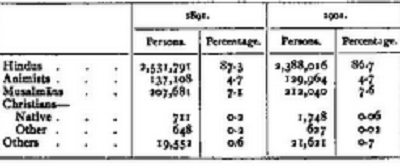

The table on next page gives statistics for religions in 1891 and 1 90 1. Hindus constituted 86-7 per cent, of the total population in the latter year. Since 1891 Hindus have lost absolutely 143,775 persons, Musalmans have gained 4,359, and Animists have lost 7,144. All other religions, the followers of which are not numerous, have gained in all 3,085. There has been a large increase in Sikhs, which is rather apparent than real, as it is attributable solely to more correct enumeration. The increase among Musalmans seems to have been due partly to their superior fecundity and partly to proselytizing efforts.

Of all the gods of the Hindu pantheon Mahadeo and Maruti (Hanu- man) probably receive the most attention. The latter has a shrine in every village. The cultivator propitiates Khat Deo, the fertilizing god, who has his habitation in a white stone set up in a field, and local gods such as Chindiya Deo, ' the lord of tatters,' are worshipped. The ' godlings of disease ' are propitiated as occasion arises. The only heterodox sect which calls for notice is that of the Mahanubhavas, or black-robed devotees, of whom a description is given in the account of RixpuR, their principal place of pilgrimage. This movement, which is a protest against polytheism, Brahmanism, and, in a less degree, the caste system, is rapidly declining. Islam presents no extraordinary features in Berar. Here, as elsewhere in India, the Musalman villager has borrowed or inherited from his Hindu neighbour or ancestor many practices which precisians would condemn as superstitious. The Gonds and Korkus, though still Animists, are tinged with Hinduism and worship Mahadeo as well as other Hindu gods, and the Korkus worship also their own ancestors, both male and female.

The oldest Hindu temples of Berar are the Hemadpanti, already referred to. More recent temples have no distinctive features. In mosques examples of both the Pathan and the Mughal styles are found.

There are 14 Christian missions at work in the province— two Roman Catholic, one Church of England, and eleven other Protestant, among whom the Methodists and Presbyterians are the most important. The activity of these missions is evidenced by the fact that native Christians more than doubled in number between 1891 and 1901. The Christian missionaries did excellent work in the famines of 1896-7 and 1899-

1900. For purposes of ecclesiastical jurisdiction Berar is in the Angli- can and Roman Catholic dioceses of Nagpur. Of the Christians in

1 901, 888 belonged to the Roman, and 626 to the Anglican Church. Agriculture supports 73 per cent, of the population, and of every 100 persons so supported 71 are workers. The preparation and supply of material substances provide a living for i\ per cent, of the people, the principal sub-orders under this head being, in the order of their importance, (i) cotton ; (2) textile fabrics and dress ; (3) food, drink, and stimulants ; (4) wood, cane, and leaves. Commerce supports 2\ per cent,, and unskilled labour, not agricultural, nearly 2 per cent.

The food of the agricultural and labouring classes consists chiefly of unleavened cakes oijowar (great millet) meal, with a seasoning of green vegetables, onions, ghl, chillies, or pulse, or a combination of two or more of these. Milk is an important article of diet ; wheat and rice are luxuries. Goat's flesh is extensively eaten by Musalmans, and less so by those Hindus to whom flesh is not forbidden as an article of diet. Few Musalmans, except those living in towns and in some of the larger villages, eat beef. It is necessary for those in smaller villages to respect the prejudices of their Hindu neighbours, many of which they have adopted. The Mahars, who are scavengers, are habitual eaters of beef in the form of carrion.

The ordinary dress of the cultivator or labourer consists of a dhoti a short jacket, an uparna or upper cloth, and a red or white turban, the former being the favourite colour. The jacket is often discarded. Brahmans and other respectable castes wear long coats, and finer uparnas and turbans. Musalmans frequently, though not invariably, substitute paijamas and a long coat for the dhoti and short jacket, and their turbans display a greater variety of colour. The dress of the women consists of a lugade and a chol'i. The former is the principal garment and corresponds to the sdri, being tied round the waist ; the long end is taken over the head, and the front of the portion forming the skirt is carried back between the legs and tucked in at the waist behind, giving the wearer a singularly bunchy and ungraceful appear- ance. The choll is a scanty bodice which confines the breasts. Muhammadan women often wear the common combination of trousers, shift, or choVi, and scarf, which is tied round the waist and carried over the head. Gond and Kolam women do not wear the choli, but conceal the breasts by drawing the end of the lugade across them. The dress of the Banjara women is especially picturesque.

The dwelling-houses of the agricultural classes are mostly of sun- dried brick roofed with thatch or tiles. Dhdbds, or flat roofs of earth, are also common. The houses of labourers consist of one or two rooms, with a small dngan or yard enclosed by a mud wall in front of the house. The houses of the well-to-do are more pretentious, consisting of several rooms opening into a rectangular courtyard, along one side of which the cattle are usually stalled. The poorest classes live in huts of hurdles or grass mats daubed with mud. In the early part of the hot season, while the grain is being threshed and garnered, cultivators move with their cattle into their fields, where they live in spacious sheds in the vicinity of their threshing-floors.

The higher castes among the Hindus burn their dead ; Musalmans, Hindus of the lower castes, and aboriginal tribes bury them. The Korkus erect posts of teak, curiously carved, at the heads of graves. Among the Mahanubhavas and some other orders of ascetics the dead are buried in salt, in a sitting posture.

The tastes of the agriculturist are principally domestic ; he has few amusements beyond his family circle except the enjoyment of village gossip, a weekly trip to the nearest market village, an occasional visit to dijalra or religious fair, or, more rarely, a pilgrimage to a shrine of more than local celebrity.

The principal festivals observed are the Mandosi, the Akshayyatritya, the Nagapanchami, the Pola, the Mahalakshmi, the Pitrapaksha, or feast to manes of male ancestors, the Dasara, the Divali, the Sivaratri, and the Shimga or Holi. The three most important feasts to the cultivator are the Holl, the Pola, and the Dasara ; and at these burn- ing questions of social precedence, often ending in criminal complaints, arise between different branches of the families oi patels or hereditary headmen of villages. At the Pola festival the plough cattle are wor- shipped. A rope called toran is then stretched across two upright poles, and the cattle of the villagers, gaily decorated, are led beneath it, headed by those belonging to members of patel family in the order of their seniority.

Hindus of all castes in Berar have three names. The first is the personal name and corresponds to the Christian name of a European, the second is the father's personal name, and the third is the family surname. Thus Ganpat Raoji Sindhya would be Ganpat, the son of Raoji, of the Sindhya family or clan.

Agriculture

The three natural divisions of Berar have already been described. The Melghat or northern division is extremely rugged, and is broken into a succession of hills and deep valleys. The hilly portion consists of basaltic and calcareous rock, and the soil in the valleys and ravines is a light brown alluvium, over- lying basalt accumulated from superficial rainwash from the hills. This light-brown soil, extending to about 8 or 10 miles from the foot of the hills towards the valley of the Purna, is cultivable, but is less rich than the soil of the valley itself. The Balaghat, or southern division, is formed of undulating high land of the Deccan trap. The plateaux are covered with fairly rich soil, and the soil of the intermediate valleys is an alluvium (;f loam of remarkably fine quality and very suitable for wheat.

The Payanghat, or central valley of Berar, contains the best land in the province : a deep, rich, black, and exceedingly fertile loam, often of great depth, with very thick underlying strata of yellow clay and lime. Where this rich soil does not exist, as in the immediate vicinity of hills, muriun and trap are found with a shallow upper crust of inferior light soil. A great deal of the Puma alluvium produces efflorescences, chiefly of salts of soda, and many of the wells sunk in this tract have brackish water. The climate of Berar has already been described. It may be briefly characterized as intensely hot and dry in the months of March, April, and May, and temperate for the rest of the year, with moderate rainfall between June and October.

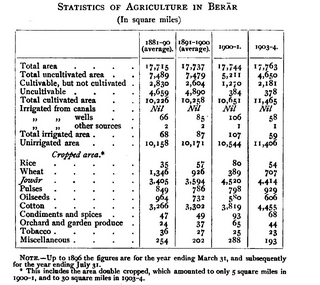

Cotton, jowdr (great millet), tiiar (pulse), and sesamum are the kharlf or monsoon crops ; and wheat, linseed, and gram the principal rain or cold-season crops. In 1903-4, of the total area cropped, nearly 87 per cent, was devoted to kharlf and 13 per cent, to rain, only 1/2 per cent, being irrigated.

The areas sown with kharif and rain crops vary according to the rainfall and market prices, and their extent is also partly regulated by the system of rotation of crops in vogue. If the rains begin well in June, a large area is sown with kharif, but if they are late more land is kept for rabi. Thus in 1891, 1,390 square miles were sown with wheat, the principal rabi crop, while in 1903-4, after several years of in- adequate late rains, the area so sown had fallen to 710 square miles.

The cultivator generally commences the preparation of his field in January. The rich black soil of the plains is not worked with the ?idngar or heavy plough for several years together, unless it should be overgrown with grass or weeds ; but the lighter soil of the upland country is ploughed nearly every year, especially when the land is reserved for a rabi crop. Ploughing is generally commenced soon after the crop of the year has been removed from the ground ; if it be deferred longer, the soil dries and hardens and becomes difficult to work. Land that has been lying follow cannot be ploughed until the first monsoon rain has fallen. Parallel furrows are not considered sufficient for hard soil, which is therefore cross-ploughed, the second operation being at right angles to the first. Harrowing succeeds, or, in the case of fields which do not require ploughing every year, takes the place of ploughing. The first harrowing is done with the moghada, a large, heavy harrow drawn by four bullocks. This turns up the earth in large clods, and brings roots, grass, and weeds to the surface. The soil is then cross-harrowed with the wakhar, a lighter implement drawn by two bullocks, which breaks up the clods and cleans the soil. In some cases the soil is harrowed again at intervals of a few days, in order that it may be thoroughly levelled and pulverized. The MarJ/" sowings take place immediately after the first regular monsoon fall of rain in June, and the rabi sowings in September or October.

Weeding is commenced when the soil dries during the first break in the rains. It is done with the daora, a two-bladed hoe which is drawn by two bullocks, and removes the weeds from two of the interstices between the rows of plants at once, the weeds growing among the plants being removed by hand. Three or four weedings in a season are generally considered sufficient, but the more industrious cultivators often use the hoe every fortnight until the crop is sufficiently strong to smother all surface weeds.

Cotton pods are usually ready for picking about the end of October, and this light work is generally done by women and children. Pay- ment is, as a rule, made in kind, each labourer receiving from one- twelfth to one-eighth of the day's picking. From the short staple variety of cotton which the Berar cultivator now grows he can obtain, if the crop is good, from five to seven pickings at intervals of fifteen or twenty days ; but the superior />ani and Jari varieties, the latter of which is now extinct in Berar, will not yield a second picking under a month, and the crop is generally exhausted in three pickings. The cultivator finds that the short staple is easier to raise and pays him just as well, for although he gets a lower price the crop is more plentiful.

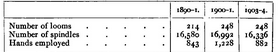

Before the establishment of ginning factories in the province almost every cultivator had his own seed for sowing cleaned by hand. Ginning by steam-power was first introduced in 1887-8, in which year there were only four factories working. In 1901 these had increased to 121, and there is every prospect of a further development of this industry.

Joivar ripens early in December, and is reaped by men, the ears being afterwards separated from the stalks by women. The stalks, called kadba or kadbi, are stacked, and 'furnish the principal fodder- supply for cattle. The ears are conveyed to the threshing-floor, where bullocks tread out the grain, moving round a central pole. Six bullocks can thresh a hhandi (about 14 cwt.) in two days. The threshed grain is winnowed in a breeze. One man stands on a tripod, while another hands up to him a basketful of grain from the threshing-floor. As he slowly empties the basket, the chaff is carried away by the wind and the grain falls to the ground.

Of the total population of Berar in 1901, 73-2 per cent, were supported by agriculture. The figures are as follows : —

Persons interested in land, landholders, tenants, co-sharers, &c. . 561,912

Agricultural labourers, &c. 1,452,221

Growers of fruit, vegetables, &c. 58')

Total 2,014,719

The principal crops in the order of their importance are cotton, jowi'tr, wheat, linseed, gram, titar or arkinr, and sesamum. Jo2vdr and wheat are the staple food-grains^ rice and k'ljra, and, among pulses, twar and gram, being subsidiary food-crops. Oilseeds are represented by sesamum and linseed ; fibres by cotton ; condiments by chillies ; and drugs and narcotics by tobacco. The cotton crop comes into the market at the end of October or beginning of November, and the supply is maintained by successive pickings throughout the cold season. Jowdr is not available till later, about January and the beginning of February. Owing to recent years of famine and scarcity, there has been an increase in the area under jowar occupied 4,414 square miles, or 38 per cent, of the whole cultivated area of the province ; and cotton 4,455 square miles, also 38 per cent.

The approximate yield per acre of the principal crops is as follows, to the nearest hundredweight : cotton, uncleaned 4, cleaned i ; j07vdr, 8 ; wheat, 6 ; linseed, 4 ; gram, 6 ; sesamum, 3 ; ti/ar, 3.

The Berar cultivator manures very little, not because he fails to appreciate the advantages to be derived from manure, but because he is unable to obtain a sufficient supply. Cattle-dung is generally the only kind procurable, and so much of this is used as fuel that little remains for the fields.

In 1903-4 only 0-7 per cent, of the cropped area was irrigated, wells being practically the only source of irrigation, which is confined, with few exceptions, to garden produce.

The necessity of a rotation of crops, to prevent exhaustion of the soil, is thoroughly understood. On light soil cotton axxd Jowdr are grown in alternate years ; on the rich black soil of the plains cotton, Jowdr, and rabi crops succeed one another. In the third year a plurality of crops will probably be grown, wheat, gram, and linseed or Iakh being raised in various plots of the same field. In the present decline of rabi cultiva- tion, cotton and Joivdr follow one another year after year on the same land, the fertility of which is thus much impaired, as the smaller cultiva- tors cannot afford to let their fields lie fallow.

The following figures show the increase of cultivation in Berar during the last twenty-four years, figures being in square miles : —

The occupied land not cropped is principally reserved for grazing. Except in Wun District, where about 7 per cent, remains to be taken up, and in the Melghat, where nearly 30 per cent, is still unoccupied, most of the cultivable land is now occupied. In Basim District much of the excess grazing land has recently been set aside for cultivation. The demand for land in Wun District is steadily increasing year by year. A decrease of cultivation in the Melghat is due to the emigration

VOL. VII. c c of Korkus in the famine of 1899-1900. Liberal concessions, which should tend to restore prosperity, have been granted.

Little is done towards the improvement of the quality of crops by selection of seed or by the introduction of new varieties, and there is no experimental farm in the province. As already remarked, the cultivator has allowed the quality of the cotton crop to deteriorate in order to obtain a greater yield. Seed separated from the fibre by the steam- ginning process is said to be less fecund than the seed of hand-ginned cotton.

A department of Land Records and Agriculture was formed in 1891, but its work has hitherto been confined to survey and settlement.

The benefits of the Agriculturists' Loans Act and the Land Improve- ment Loans Act are naturally appreciated most highly in years of scarcity and famine. The delay in disbursing loans allowed under these Acts was for a long time an obstacle in the way of their popularity, but experience gained in years of famine has led to the simplification ot procedure ; and there seems to be a fair field for the success of agri- cultural banks.

The very few horses in Berar are inferior animals and merit no notice. Ponies are more numerous, but are weedy. An attempt was made by Government for a few years to improve the breed by keeping Arab stallions at the head-quarters of Districts, but was abandoned about 1 893 as a failure. The breed of cattle proper to the province is known as Gaorani or Berari, of which there are two distinct varieties, the Umarda and the Khamgaon, the former being the smaller. Animals of this breed are hardy, active, and enduring, and can easily cover 30 miles within six or eight hours. A pair will sometimes cover 40 or 50 miles in a day. The Khamgaon breed is more adapted to heavy draught. This breed is found in the Khamgaon, Balapur, ChikhlT, Jalgaon, and part of the Akot tahiks ; the Umarda breed elsewhere. Indiscriminate crossing, the neglect of stock cattle, and fodder famines have contributed to the deterioration of both breeds. On the eastern borders there are very distinct indications of the influence of the Arvl or Gaulgani breed, and on the southern border of that of the breeds of cattle found in the Nizam's Dominions. The recent prevalence of famine has necessitated the importation of working, and, to a smaller extent, of milch cattle. The breeds most commonly imported have been the Nimari, Sholapuri, Labbani, and Hoshangabadi ; cattle of the Malwi, Gujarati, and Surati breeds are less frequently seen.

Buffaloes in the north and east of the province are of the Nagpuri, and elsewhere of the Dakhani breed. Since the famine of 1899-1900 buffaloes have been imported from Central India. These, which are distinguished by the comparative smallness of their heads and horns, are locally known as Malwi. The sheep and goats are inferior animals, and the herdsmen, mostly Dhangars, lack the means and the knowledge necessary to the improvement of the breed. In towns goats of the Gujarat breed are found, and these are said to be good milch animals.

Large Umarda bullocks fetch about Rs. 60 to Rs. 70 each, small Umarda bullocks from Rs. 30 to Rs. 40, and Khamgaon bullocks from Rs. 50 to Rs. 70. Bullocks of other breeds cost from Rs. 25 to Rs. 40 each, and cows from Rs. 10 to Rs. 25, the Berar cow being a poor milch animal. Buffaloes are sold at from Rs. 20 to Rs. 70 each, sheep at from Rs. 2-8-0 to Rs. 3-8-0, and goats at from Rs. 3 to Rs. 10. The price of a pony varies from Rs. 25 to Rs. 50.

Cattle suffered severely in the scarcity of 1896-7 and the famine of 1899-1900, and the mortality was great; but large importations have gone far towards making good the deficiency. The grazing lands are sufficient, except in parts of the Purna valley, such as the Akot and Daryapur taluks. In the upland country almost every village has a certain area of land set apart for free grazing. In 1903-4 the grazing area was 335 square miles, of which 245 were Government land set apart for free grazing and 90 were held by private occupants. Kadba, Q>x jowdr stalks, form the principal fodder-supply, and the plough cattle of the richer cultivators are partly fed on cotton seed.

There is only one cattle fair in the province, held at Wun in February or March. Some fine cattle are brought to this fair and fetch good prices ; but the fair has not been regularly held of late years, for fear of importing plague. Ponies are brought in considerable numbers to the Deulgaon Raja fair in Buldana District, held in September in con- nexion with the festival of Balaji. The principal weekly cattle markets in the province are those at Umarda, Digras, and Nandura.

Rinderpest, foot-and-mouth disease, and anthracoid diseases, such as charboti symptoDiatiqtie, are the commonest infectious diseases, the two former being much more frequent than the third. Anthrax is rare, and sitrra has occurred only once among the ponies on a dak line. The Civil Veterinary department has published a leaflet of instructions for the prevention of the spread of contagious diseases. This has been widely circulated ; a system of registration of cattle disease has been introduced ; and on receipt of reports of outbreaks veterinary assistants are deputed to carry out suppressive measures and to treat the sick. Veterinary dispensaries are being established at taluk head-quarters. The publication of a manual of simple veterinary instructions in the vernacular has been delayed for want of funds. Bacteriological re- searches have been commenced, and inoculation with anti-rinderpest serum is carried on.

Irrigation is rare except for garden crops, which are irrigated almost entirely from wells, the water-lift being the mot ox leathern bucket, raised by two bullocks. The average cost of construction of a permanent well

c c 2 is from Rs. 300 to Rs. 500 when specially expensive blasting operations have not to be undertaken, or from Rs, 10 to Rs. 15 per foot of depth ; and the area irrigated by a single well is about four acres. The depth of permanent wells varies from 20 to 90 feet. Temporary wells, such as those found in Gujarat, are not in use in Berar, as the water is not sufficiently near to the surface ; but excavations known as jhiras are very commonly made in the beds of streams, in the hot season, for the purpose of obtaining drinking-water.

Rents ,wages and prices

Berar being settled on the ryotwari system, the rent of a cultivator may ordinarily be taken as the land revenue paid by him to Govern- ment. In the comparatively few villages held under and Brices ' other tenures, the holder of the village is not in any way restricted by legislation as regards the rent which he is entitled to demand, except that in ijdra villages those tenants who occupied their holdings when the village was leased are entitled to hold at rates not exceeding those demanded by (Tovernment for similar land in adjacent khdha villages. This privilege is restricted to land actually held before the lease. The control of rent by legis- lation has not been found necessary, for rack-renting is impossible at present. Statistics of rent actually paid in alienated villages are not available ; but the Government assessment per acre, which may be taken as a fair standard, varies from Rs. 2-12-0 to Rs. 1-14-0 in the Payanghat and from Rs. 2-0-0 to Rs. 1-2-0 in the Balaghat. Of tenants holding under occupants there are three classes : tenants paying money rent, tenants paying rent in kind on the batai system, axid potld- 7va)iiddrs or tenants-at-will, who pay rent either in money or in kind, the landlord meeting the revenue demand. The batai sub-tenure, which is in all respects similar to the mezzadria or metayer system, is very common in Berar, but less so than formerly, as it is being replaced by leases for money, owing to much of the land having fallen into the hands of classes which do not cultivate. Statistics of the money rent usually paid are not available. The ordinary conditions of batai are that the lessor receives half the produce and pays the land revenue, while the lessee bears all the expenses of cultivation and takes the other half. Sometimes the lessee contributes a proportion, not ex- ceeding one-third, of the land revenue, or agrees to pay half the land revenue and hands over to the lessor one-fourth only of the produce. For garden land the lessee, as a rule, delivers only one-third of the produce, as the expense of cultivating land of this class is heavy.

The average daily wage for the last thirty years is R. o-i 1-7 for skilled and R. 0-3-4 for unskilled labour, the rates for the province in different years ranging between R. 0-12-9^ and R. 0-9-1 and R. 0-3-11 and R. 0-2-7. The lowest rates are those of the famine year 1899- 1900, when food was only less costly than it was in the following year. There was a similar though far less marked fall of wages in 1896-7, which was a year of scarcity and high prices, and it has been observed that wages do not rise with the rise in the price of food. In years of famine, however. Government steps in as an employer of labour, and provides all those in actual want with a living wage.

^Vages vary from year to year in different Districts and localities, but the variations are not constant and are due to ephemeral and not to permanent local conditions. The Melghat taluk, where wages are ordinarily lower than elsewhere, is an exception. Though wages have from time to time fluctuated during the past thirty years, they have, on the whole, varied so little that it cannot be said that they have been affected by the introduction of factory labour. The railway has, how- ever, reduced wages for skilled labour, which could always command R. I per diem before the railway, by facilitating communication, brought the rate down to that which prevailed in other Provinces.

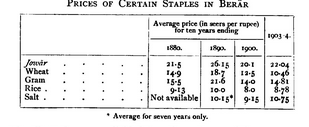

The average prices of the principal food-grains, in seers and chittacks per rupee, in 1903-4 were as follows : jowdr, 22-1 ; wheat, 10-7 ; gram, 14-13; rice, 8-12. These are slightly above the standard, but prices were much disturbed by the famine of 1 899-1 900, and are returning to the normal by slow degrees. Prices vary considerably in different Districts from year to year ; but as the variations are not constant, they furnish no materials for an estimate of the conditions of any particular locality.

The increase in the cultivated area seems to have had no effect on prices, but the natural tendency of this increase towards the reduction of prices may have been counteracted by the improvement in means of communication. This improvement has not affected the price oijowdr, which is not grown for export ; and though wheat is dearer now than it was thirty years ago, it is doubtful whether the rise in price is due to increased facilities for exportation. The effect of famine on prices is very marked. Thus in 1895-6 joivdr sold at nearly 23 seers for the rupee, while in the following year, which was a season of scarcity, only I if seers could be obtained for that sum. In 1898-9 a rupee purchased 27^ seers, but in the famine year which followed it would purchase no more than 18^ seers, in spite of low prices in the early part of the year; while in 1900-1 the average rate was seers for the rupee, 5, 6, or 7 seers being the ordinary rate during the first six months of the year 1900, when the effects of the famine were most severely felt.

Another cause sometimes operates to reduce the price of grain. Thus, in 1 880-1, 38 seers, and in 1884-5, 30^ seers oi joivdr could be purchased for a rupee. The fall in price was attributed in each case to the late rains, w^hich in the former year made it impossible to store grain, and in the latter damaged the grain already stored.

The standard of comfort in Berar, though not high, is probably no lower than in any other rural tract in India. The house of the middle- class clerk, for which he probably pays a rent varying from Rs. 2 to Rs. 10 a month, is scantily furnished. His food costs him but little, for he is, in all probability, a Brahman, and therefore a vegetarian ; but he uses such luxuries as wheat, rice, milk, ghi, and sweetmeats more freely than does the cultivator. His clothes are of fine cotton cloth, the dhoti having usually a border of silk, and he wears a silken turban ; but the whole outfit is so seldom renewed that it costs him com- paratively little. The cultivator's style of living and the character of his house depend on the size of his holding ; but the distinction between the well-to-do and the impoverished cultivator consists largely in the quantity and quality of the jewellery worn by the women of the family. The cultivator's clothes are of coarse cotton cloth. The labourer's standard of living is similar to the cultivator's, but lower. His house is smaller and meaner, his cooking pots fewer, his food scantier, and his family jewellery less costly. There has been no perceptible change in the standard of living of these classes. So little does the cultivator understand physical comfort that when he was suddenly and temporarily enriched by the rise in the price of cotton, which was one of the results of the American Civil War, he was sometimes unable to find a better outlet for his wealth than the replacement of his iron ploughshares and cart-wheel tires by shares and tires of silver.

Forests

The Berar forests are divided into three classes : (A) areas reserved