Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Allies

2014-22: 19 allies lost

Mohua Chatterjee and Koride Mahesh, February 16, 2022: The Times of India

From: Mohua Chatterjee and Koride Mahesh, February 16, 2022: The Times of India

TRS's majority in the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation also declined from 99 corporators to 56 in the December 2020 polls, with BJP surprising everyone and fortifying its credentials as KCR's principal challenger. The civic body, with 150 seats, is seen as a bellwether for at least 25 of the 119 assembly seats in the state.

With the veneer of friendly distance from BJP scraped off, KCR is now letting it all hang out.

Not the only BJP ally to walk away

Last year, one of the BJP's oldest allies, Shiromani Akali Dal broke away from the NDA, protesting against the three farm bills the Central government had passed. The BJP was forced to withdraw the legislations later in the year, but the partnership broke.

A year earlier, in November 2019, Shiv Sena, one of the biggest constituents in the NDA, snapped ties with the BJP soon after the Maharashtra assembly election results were out. The Sena accused the BJP of going back on its promise of equal division of power in the state and eventually went on to form the government with other allies.

And in 2018, Chandrababu Naidu's Telugu Desam Party ended its alliance with the BJP over denial of special category status to Andhra Pradesh. In all, the BJP has lost 19 allies, big and small, since it came into power in 2014.

Caste and the BJP

2021: Reservation in medical colleges

Radhika Ramaseshan, August 2, 2021: The Times of India

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who did not start off as a votary of Mandal politics, discovered an Eldorado in the OBC votes after realising the futility of balancing competing caste interests by crafting “rainbow coalitions”. As Mandalisation reached its fruition, caste has today become a zero sum-game. A political leader can’t make the Brahmins smile and applaud, while handing out goodies to the OBCs and Dalits. One class gains, the others lose. There are no two ways about the formulation.

If we haven’t yet seen medicos on the streets with brooms and cooking appurtenance — they invariably protested with objects identified with “lowly” jobs when similar moves were introduced by non-BJP dispensations — it’s because the latest one comes with a take-it-or-leave-it addendum. There’s a ten per cent quota for the “economically weaker sections” (read the upper castes) in state medical and dental colleges — new paradigm of social justice was how Modi described it. The BJP’s engagement with the OBCs and Dalits in the heartland is tortuous yet fascinating.

Unlike a lethargic and smug Congress, it was quick to put its finger on the Mandal pulse and discern that unless it tapped the vast expanse of the dissimilar and divided OBCs and Dalits — and put in place winning electoral equations — it would leave the field open to the socialists and leaders like Kanshi Ram. Every layer of the R S S hierarchy was composed of the upper castes. The BJP was relegated to provincial towns. It had a following largely among the mercantile community, that was looked on askance by the Brahmins, while the OBCs and Dalits submitted to its dictates because the money-lenders and pawn-brokers were their lifelines to survival. The BJP had to break through a wall of indifference (from the Brahmins and Rajputs who were wedded to the Congress) and fear from the OBCs and Dalits.

The R S S beguiled some OBCs, notably the Lodh-Rajputs, by feeding them a diet of Hindutva that made them feel like the upper castes without giving upward mobility in intrinsic terms. There was no way the “jajmani” system would be overturned; a Lodh-Rajput could never hope to become a religious preacher. Likewise for those Dalits (Khatik, Valmiki) who were often used as the frontend in clashes with Muslims, but could never think of becoming BJP office-bearers. Bangaru Laxman, the only Dalit to become the party president, was an aberration and that too didn’t last long.

The BJP’s tactics to penetrate the OBCs and Dalits are a textbook case of “Chanakyaniti” (long before Amit Shah claimed the Chanakya title) fused with hard-nosed politics. It fumbled along the way. It was not easy to cross step one that entailed identifying and projecting OBCs from its own ranks like Kalyan Singh, Uma Bharati, Vinay Katiyar and Shivraj Singh Chouhan, who were deeply resented by the Mishras, Tiwaris, Singhs and Guptas. It was edifying for the BJP to delve into history and rediscover the little gods and goddesses who meant much more to many OBCs and Dalits than the caste Hindu trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, or Ram and Krishna. The BJP used these deities as convenient symbols and gradually incorporated them in a larger line-up of celestial beings. However, personas and symbols are useful up to a point.

In a colossal entity like the BJP, a Kalyan Singh or an Uma Bharati were challenged by powerful upper caste interests and even they lost their jobs eventually. Even Modi, a backward caste politician, was initially circumspect about embracing his caste publicly. He preferred to be known as the monarch of the Hindu heart. His second success in 2019 and the UP victories resolved the caste versus a pan-Hindu identity debate for Modi. He seems to have settled for an identity as an OBC leader, probably knowing that the upper castes had no choice but to stay with the BJP.

Closer to the UP elections, he and the BJP will probably have another think because the “savarnas” are not monolithic. The Brahmins seem to be casting about for an alternative, which is why the SP and the BSP have started wooing the community and its Ram “bhakts”.

The Centre’s latest decision is nowhere as tectonic as the Mandal Commission’s proposals, which caused violence and the death of many young people, and resulted in a fundamental shift in north Indian politics, undermining the uncontested dominance of the upper castes. At best, this is a mild aftershock that has nonetheless touched a raw nerve, proving just how unpalatable a minor concession to the OBCs is to the “savarnas”, even now.

In 2019, when the Chhattisgarh government increased the OBC quota from 14 per cent to 27 per cent, upper caste youths were out sweeping the roads as though they had lined up to get the job of “safai karamcharis”. A political observer accurately pointed out that the division of labour, sanctified by the odious caste system, was based on the “dogma of predestination” and not choice.

Has Modi pushed the frontiers of OBC empowerment? Yes. He is unlikely to forsake the Mandalised facet of his political persona. The development portends another interesting chapter in the BJP’s evolution. Perhaps, Yogi Adityanath will henceforth address the Hindutva constituency and the upper castes more stridently.

Radhika Ramaseshan keeps an eagle eye on all that's hot in the corridors of power

Constitution

Religion, and Rule 10(a)

y Shyamlal Yadav, June 7, 2022: The Indian Express

Religion in the BJP’s constitution

Article II of the BJP’s constitution lays down the “objective” of the party, which was formed in 1980 by the members of the erstwhile Bharatiya Jana Sangh who left after the collapse of the Janata Party experiment.

The objective of the BJP says: “The party aims to establish a democratic state, which guarantees to all citizens irrespective of caste, creed or sex, political, social and economic justice, equality of opportunity, and liberty of faith and expression.”

The party constitution contains 34 articles. Along with filling in party membership forms, one has to take a pledge that “I subscribe to concept of Secular State and nation not based on religion… I undertake to abide by the Constitution, Rules and discipline of the Party.”

The rules of the party

Article XXV-5 states: “National Executive will frame rules for the constitution of Disciplinary Committee at different levels for deciding matters relating to violation of discipline.” The rules are listed at the end of the constitution, along with details of the necessary action, and the process of action.

A 10-part process is listed as part of “disciplinary Action” in case of breach of discipline. Six types of breach of discipline are listed.

Rule10(a) of the BJP constitution

Rule 10 gives extraordinary powers to the party president to discipline members. It says: “The National President if he so desires, may suspend any member and then start disciplinary proceedings against him.” It is under this rule that Sharma has been suspended even before an inquiry against her.

Para (a) under “Breach of Discipline” states: “Acting or carrying on propaganda against programme or decision of the Party.”

Under the rules, “Disciplinary Action Committee of not more than 5 members will be constituted… Committees shall draw their own procedures; State Disciplinary Action Committee can take action only against units subordinates to it…;

“On receipt of a complaint, the National President or the state president…may suspend an individual or a Unit followed by a show-cause notice within a week of the said order; “Maximum 10 days’ time from the date of receipt of such notice may be given to a person to reply…;

Economic policy

2014-21: from 'pro-industry' to populist

August 17, 2021: The Times of India

The Congress might have minimised PV Narasimha Rao’s deft political management of a sinking Indian economy in 1991, but it never disavowed the former prime minister’s unorthodox break with a socialist regime to embrace a liberalised economic order — not even after it lost the 1996 elections. When prodded by criticism, the Congress glazed over Rao’s legacy with a veneer of empathy (reforms with a humane visage), verging on apologia. The Congress’s 84th plenary in 2018 enshrined Rao’s reforms as “truly historic” in the party’s annals. In other words, there was no confusion, only modulation.

The BJP was always woolly about economics, except for glimpses of clarity, cogency and determination in Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s time when Arun Shourie was the prime influencer. Indian industry’s big hitters banked on Narendra Modi for a 1991 resurgence. As the host of the biennial Vibrant Gujarat summits when he was chief minister, he came across as an uncompromising votary of economic reforms. There was not a hint that the R S S, or the asteroids swirling in its orbit which crash-landed on Vajpayee every now and then, figured in Modi’s scheme of things. He had a way of dealing with the Swadeshi Jagran Manch, the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh and the Bharatiya Kisan Sangh, to force them to lie low in Gujarat. The Sangh satellites are pretty animated these days because they think they can leverage their “clout” as the economic challenges increase and the government appears a tad vulnerable.

On August 12, the Prime Minister called on the corporate sector to take advantage of a raft of “reforms” his government introduced, notably the move to discard the 2012 retrospective tax amendment and certain correctives to decriminalise economic offences and scale up investments. Modi stressed that for him reforms were a “matter of conviction”. A day later, in the same forum, Piyush Goyal, the commerce minister, assailed the industry for seeking out “foreigners” as business cohorts and for partnering “falana-dhimkana” (anyone and everyone). It wasn’t a critique or a jeer, the words were a wallop. The minister singled out the Tatas — incidentally an early endorser of Modi when India Inc had serious reservations about him post 2002 — for attack.

Goyal’s a pro when it comes to handling the industry. He’s a Mumbai boy, was the BJP treasurer for years like his father, the late Ved Prakash Goyal, and is no stranger to the inner clubs of Bombay and Bangalore. Did he flub in an intemperate moment? Was it an intended rap? Why?

Nobody has a persuasive explanation. Industry speculation is that Goyal is furious with the Tatas for opposing some clauses of the proposed Consumer Protection (e-commerce) rules, 2020 at a government-industry meeting in July. Goyal is also the consumer affairs minister and wanted to enforce these rules, while both Amazon and the Tatas, who have just stepped into the e-commerce space, sought more time to study the changes. The new rules proscribe sales by group companies that have a link with the e-commerce site owner.

Among other pressure groups, the Sangh-patronised Confederation of All India Traders, or CAIT, headed by Praveen Khandelwal, a Delhi trader and a former activist of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), has Goyal’s ear. In January 2020, when Amazon’s Jeff Bezos visited India, the government snubbed him. A reported meeting with the PM never happened. Khandelwal led a traders’ protest, which he likened to the British-era demos against the Simon Commission, raising “Bezos go back” slogans when Bezos held a meeting with small and medium entrepreneurs in Delhi. Khandelwal said Amazon was like the East India Company and rubbished Bezos’s promised investment of $1 billion to help Indian traders get digital savvy.

Not surprisingly, Khandelwal, whose CAIT also campaigned relentlessly against Flipkart, was quick to laud Goyal for “prioritising national interest above self-interest” and upholding the rights and interests of 80 million small and medium traders, “whose survival”, he said, was imperilled by corporate houses “colluding with multinational giants to plunder India’s retail market”. The swadeshi angst at work?

Is the CAIT so powerful as to push Goyal to the brink of a fracas with the industry? A dive into the BJP’s recent past edifies aspects of the relationship between the party and the Sangh’s economic progeny, and explains why the BJP, despite being in power for a reasonably long time, has not evolved a well-thought-out economic policy.

Gautam Mehta, an analyst with the International Finance Corporation, Washington, in a paper for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, writes, “The selection of the business-friendly Modi, who campaigned on a platform welcoming foreign investment and who was less enamoured with the virtues of small, family-run businesses, suggested that the BJP was evolving into a more conventionally centre-right political party, and that the party was moving away from the statist and autarkic proclivities of the Sangh.”

What happened?

Mehta says political exigencies (remember this is a BJP-majority government) and “pressure” from the Sangh pushed the government’s economic policies in a “more populist direction”. “The increased convergence between the Sangh’s economic populism and the government’s own policies... led the BJP to dilute, de-emphasise, or even abandon some of its more market-friendly campaign promises,” he writes, citing the government’s e-commerce draft protection rules as an example designed to hinder the operations of Flipkart (Walmart majority-owned) and Amazon. Vajpayee kept the swadeshi lobbyists at bay but paid a price when the Swadeshi Jagran Manch lampooned him in its in-house magazine. This was when he was the PM. Dattopant Thengadi, the BMS founder and a lifelong “pracharak” —whose book The Third Way is believed to be the foundation of Modi government’s concept of poverty-alleviation programmes — publicly abused Vajpayee’s finance minister Yashwant Sinha. Guess who issued a statement against Thengadi, whose name still evokes reverence in the Sangh? Modi.

As the then BJP general secretary, Modi noted that the “content and tenor of Thengadiji’s censure of the NDA government... leaves us with no option but to counter his criticism”. The PM’s instincts may be pro-industry but the swadeshi faithful leave him with no choice but to unleash the likes of Goyal on corporate czars from time to time.

Radhika Ramaseshan keeps an eagle eye on all that's hot in the corridors of power

=Election performance=

2024

See graphic:

The performance of the BJP and the Congress in the various states of India in 2024, a seat- wise map

Ideology, strategy

Use of Gandhianism

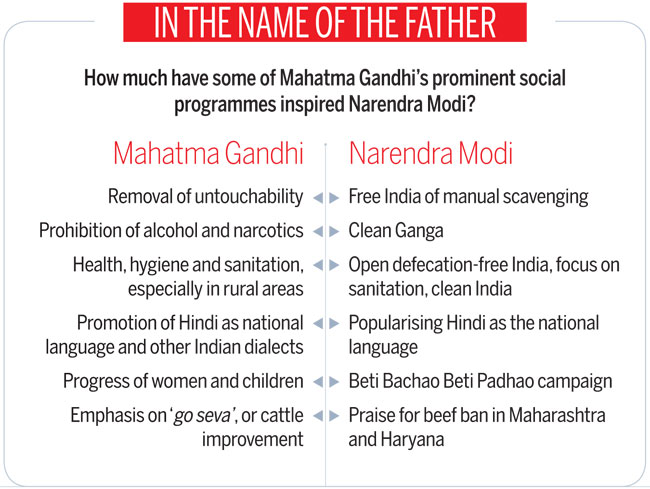

If the 20th century belonged to the Congress, Modi eyes the 21st for the BJP. And to shape that pan-India dream, the saffron party looks at Gandhi's model that worked for the grand old party.

On June 9, 2013, soon after he was anointed the BJP's election campaign committee chairman for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, Narendra Modi addressed party workers and spelled out the catchphrase that would be his mantra in the run-up to the polls, and even after a grand victory: "A Congress-mukt Bharat is the solution to all problems facing the country." An India free of Congress, Modi said, and almost delivered it a year later.

Irony then that it is the same Congress, though from a different era, that Modi's BJP now seems to be emulating to become the new pan-India national party, replacing India's original national party. At the party's first National Executive under Prime Minister Modi on April 3-4 in Bengaluru, the BJP appeared to continue its walk towards embracing the Congress of yore-the Congress under Mahatma Gandhi. Having relegated the grand old party to a poor second slot in vote share-its 172 million votes versus the Congress's 107 million in the General Election-the BJP now aims to be where the Congress has been all these years: in every ward of every city and town, and in each village of each taluka. And to achieve that, the party is taking lessons from what the Indian National Congress did when it spread its wings in the run-up to Independence.

Ease the entry barrier

In 1920, a Congress session was held in Nagpur and the party which was spearheading the Non-Cooperation Movement decided to penetrate deep into India's villages by easing its entry barrier. The Congress slashed the membership fee to four annas (25 paise) to let the poor, especially the non-urban, join in and help erase its image of a clique of English-educated urban elites. Nearly 95 years on, the stage was set for another party to take wings and spread itself soon after Modi took oath as the prime minister on May 26, 2014. Addressing the party's National Council meet at the Capital's Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium in August, BJP President Amit Shah put that ambition into words: "For long, the Congress's ideology has been predominant in India's politics Now the time has come to spread our ideology and to leave an imprint on the nation's politics."

Like the Congress did after the Nagpur session, the BJP began that journey by easing the entry barrier. It made membership free, and got mobile technology to its advantage. Prime Minister Modi began the membership drive on November 1 last year by dialling a toll-free number. And by the time the BJP marked its 35th foundation day on April 6, it claimed to have received more than 160 million 'missed' calls and registered about 95 million members. That's up from less than 35 million members last year. Initially scheduled until March 31, the drive has been extended by a month as the party hopes to enlist 100 million members by then.

But BJP leaders say this is just the beginning. Modi and Shah's aim is taking the party to virtually every village, a feat matched only by the Congress in its heyday. "As a convenor of the membership drive I have visited 19 states but the BJP president will have visited every state of the country by the end of April to take stock of enrolment and guide the process," party Vice-President Dinesh Sharma says.

Strike the right chord

In February 1922, as the euphoria over the Non-Cooperation Movement began to recede after he suddenly called it off, Mahatma Gandhi hit upon a unique idea to endear Congress to the masses. He exhorted Congress workers to engage with the people, especially the marginalised and the underprivileged, and get involved in non-partisan constructive programmes such as spinning khadi, promoting Hindu-Muslim unity, fighting untouchability and working among people from tribal and lower-caste communities, among others.

Likewise, Modi began with a call to make India free of open defecation last August, during his first Independence Day address, and launching Swachh Bharat Abhiyan on Gandhi Jayanti. He repeated the call at the Bengaluru National Executive. Shah responded by constituting a committee comprising senior party members such as Prabhat Jha, Purushottam Rupala, J.P. Nadda, Vijay Goel and Makhan Singh to oversee the programme.

The Prime Minister has urged BJP leaders and workers to be involved in other socially constructive programmes such as freeing India of manual scavenging, gender sensitisation and cleaning rivers. The trusted lieutenant in Shah responded to the call by setting up separate committees to oversee these tasks. Following Modi's efforts at fighting female foeticide and championing education for girls, Shah announced the Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (save girls, educate girls) campaign and asked party cadres to ensure its implementation.

Modi has also stressed the need for clean rivers, particularly the Ganga. The PM is believed to have highlighted that the party can organise campaigns to clean the river that passes through nearly 6,000 villages and more than 1,800 towns. While Modi spoke of environmental benefits of the programme, it is also seen as an effort to shore up the party in the politically crucial Hindi heartland states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, which go to the polls later this year and in 2017 respectively.

Charting new yet known course

Apparently taking it up from where the Congress left, Modi, according to Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, said in Bengaluru that the party should mark Deendayal Upadhyaya's birth centenary to work for the welfare of the poor-in keeping with the Jan Sangh leader's philosophy of Antyodaya, which talks about the welfare of even the last person in society. If Gandhi's talisman guided the Congress's efforts to widen its reach, the BJP has got the wherewithal to popularise Upadhyaya's talisman of Antyodaya.

Party leaders have been asked to work towards eradicating manual scavenging, prompting Shah to urge the cadres to reach out to nearly 2.3 million households employed in manual scavenging and ensure their rehabilitation. "These activities, which go beyond politics to social reform campaigns, will show BJP as a party with a difference," Union minister Prakash Javadekar said quoting Shah.

The BJP, party spokesperson Sudhanshu Trivedi says, is not only a political party but also an ideological movement. These socially constructive activities may look out of place in political activism but Gandhi too had demonstrated their efficacy in connecting the freedom struggle with the masses. These programmes will help the party connect better with the people, and help it fortify its position across India, Trivedi justifies.

To be sure, it's not exactly an all-new idea. The saffron leadership has always believed that one huge factor that allowed the Congress to remain in popular imagination even post-Independence was due to its projection as the party that got India freedom. And the second is the perception that the Congress has, since its formation, worked for social good. But this is the first time that the saffron party is putting those ideas and aspirations into words. In a "Congress-mukt India", it seems a Modi-led BJP seeks to chart a route similar to that of the Congress under the Mahatma.

For a party known for its organisational structure, its leader and his closest aide have given an insight into how these elaborate socio-cultural and political ideals would be put into action. On April 2, Modi exhorted BJP national office-bearers, state unit chiefs and state organising secretaries to ensure that a large number of BJP members enrolled by the ongoing drive joined the movement as political workers. The following day, Shah announced an ambitious target of training 1.5 million of these members in political activism. In a massive programme, party workers will connect with the 100 million newly registered members from May to July.

But once time takes the sheen off this idealism, will the BJP parrot the Congress, which dumped many Gandhian goals after assuming power post-Independence? Will they remain limited to photo-ops, like the Swachh Bharat campaign was in the Capital, with garbage specially assembled for Delhi unit chief Satish Upadhyay to wield the broom? Gandhi's moral authority inspired ordinary Congressmen to work for social good, which endeared the party to the masses. Notwithstanding the brute majority of Modi's government, the only moral authority a committed BJP member understands. So Modi's grand design to mainstream saffron nationalist ideology among the masses will depend to a large extent on the synergy with Nagpur's drives.

2014- Aug 2017: change in strategy

Not long ago, BJP would not have decided to put up a candidate against Ahmed Patel in the Rajya Sabha polls in view of the fact that the powerful Congress leader had numbers far more than required. That the saffron party made an audacious bid to wrest the seat from powerful adversary is testimony to the transformation brought about by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and BJP chief Amit Shah in a party which could not prevent the defeat of Vajpayee government in Lok Sabha by a solitary vote in 1999.

Under Modi and Amit Shah, BJP seems determined to ensure that humiliation of April 1999 becomes a distant memory and the party does not lack a killer instinct that has often saddled it with a “choker“ tag in the past.

In the last three years since Modi became PM and Shah took charge of the party , BJP has outdone Congress and other rivals in the demanding art of realpolitik. In the most recent round of assembly elections, it pipped a lethargic Congress to forming governments in Goa and Manipur despite ending up second.

BJP has expanded its coalition in the northeast with NDA governments in office in Arunachal Pradesh while it has a friendly government in Nagaland. The party has adopted some of Congress's tactics in wooing legislators and leaders.BJP has pragmatically turned defections into political alliances, leading to governments in Uttarakhand and Assam where imports played an important role in sealing electoral victories.

In the Gujarat Rajya Sabha elections, BJP relied on Congress rebel Balwantsinh Rajput to pose a stiff challenge to Congress leader Ahmed Patel and this is the latest reflection of the party's aggressive tactics in taking on rivals and spare nothing when it comes to grabbing an opportunity .

The party has junked an approach often marked by a readiness to compromise, a reflection of a leadership with reasons to feel vulnerable, and embraced an “attack as the best form of defence“ mode.

In case of Gujarat Rajya Sabha polls, statistics suggested that three candidates, including BJP president Amit Shah, Union minister Smriti Irani and Patel, could have easily won as there were three vacancies and Congress had more than 45 MLAs, the minimum number to win.

But Congress leader Shan karsinh Vaghela's rebellion saw a panicked Congress bundling its 44 MLAs to Bengaluru. Interestingly , Vaghela had rebelled against the BJP government in 1996 and brought down the BJP government under Suresh Mehta to become chief minister with Congress support. It was BJP that tried to protect its flock at a resort.

The recent resignations by SP and BSP MLCs paving the way for some of Uttar Pradesh CM Yogi Adiyta Nath's ministers is another sign of a new BJP . MLCs had quit on a day when Shah was in Lucknow, making it clear that aggressive tactics will not stop after elections are over. In January , BJP captured power in Arunachal Pradesh after 33 of the 43 People's Party of Arunachal (PPA) MLAs, including CM Pema Khandu, joined the saffron party . This is the second time in 13 years that BJP is in power in the politically volatile border state.

BJP's success in mending forces with Bihar CM Nitish Kumar and the high profile it has given to opposing violence by CPM against its workers in Kerala and the combative posture against West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee are more of the same.

‘Nation first, party next, self last,’ LK Advani

The guiding principle of my life has been ‘Nation First, Party Next, Self Last.’And in all situations, I have tried to adhere to this principle and will continue to do so.

The essence of Indian democracy is respect for diversity and freedom of expression. Right from its inception, the BJP has never regarded those who disagree with us politically as our “enemies”, but only as our adversaries. Similarly, in our conception of Indian nationalism, we have never regarded those who disagree with us politically as “anti-national”. The party has been committed to freedom of choice of every citizen at personal as well as political level.

Defence of democracy and democratic traditions, both within the Party and in the larger national setting, has been the proud hallmark of the BJP. Therefore BJP has always been in the forefront of demanding protection of independence, integrity, fairness and robustness of all our democratic institutions, including the media. Electoral reforms, with special focus on transparency in political and electoral funding, which is so essential for a corruption-free polity, has been another priority for our Party.

In short, the triad of Satya (truth), Rashtra Nishtha (dedication to the Nation) and Loktantra(democracy, both within and outside the Party) guided the struggle-filled evolution of my Party. The sum total of all these values constitutes Sanskritik Rashtravad (Cultural Nationalism) and Su-Raj (good governance), to which my Party has always remained wedded. The heroic struggle against the Emergency rule was precisely to uphold the above values.

It is my sincere desire that all of us should collectively strive to strengthen the democratic edifice of India. True, elections are a festival of democracy. But they are also an occasion for honest introspection by all the stakeholders in Indian democracy – political parties, mass media, authorities conducting the election process and, above all, the electorate.

2019/ Christian outreach in Mizoram

July 25, 2019: The Times of India

Mizoram BJP sets up missionary cell to shed 'Hindutva' tag

AIZAWL: Seeking to shake off the image of a "pro-Hindu party", BJP on Wednesday set up a missionary cell in Christian-majority Mizoram, the only state in the Northeast where it is not part of the government.

"We want to allay fears that BJP is pro-Hindu and anti-Christian," said J V Hluna, president of BJP's Mizoram unit, while inaugurating the cell at the party's state headquarters. The cell will run a 24x7 helpline for Mizo missionaries. "It has been established to help any Christian Mizo missionary in need of help through BJP functionaries across country," Hluna said.

He clarified that BJP being "a secular party", the objective of the missionary cell was not to propagate Christianity anywhere.

Mizoram remains the lone outlier in the otherwise saffron Northeast map. BJP is not part of the government here despite the Mizo National Front, an NDA ally, being in power.

The only constituency BJP won in the 2018 assembly election, its first in the state's history, was the Chakma-majority Tuichawng seat. Although the party has tempered its Hindutva in its quest for acceptability, Mizoram appears to have walled itself from the BJP wave.

The missionary cell will now create a database of the 5,000-odd Christian missionaries in the state, with their names, addresses, phone numbers and email IDs.

The plan has already triggered a debate about the potential security implications of the process.

BJP dismissed these concerns, with missionary cell head Lalhriatrenga Chhangte denying that the party had any motive other than the stated one. "There was some misunderstanding about data on missionaries, some apprehension that it could fall into the hands of R S S. But contact details of missionaries will be on the database only with their consent...The sole purpose of this cell is to help those in need."

He added, "BJP's Mizoram unit will always oppose R S S or any other organisation that violates the freedom of religion and acts against Christian missionaries."

Luring MPs, MLAs from other parties

North-east India

2014-2022, September

September 4, 2022: The Times of India

GUWAHATI: Pitching camp from one state to another in the northeast, BJP has brought into its fold 93 legislators from other parties in the last eight years - a number more than twice the strength of the 40-seat Mizoram assembly.

The switchover of five JD(U) MLAs in Manipur late on Friday was BJP's 15th snatch in the region since the one in Nagaland in 2014 when three NCP MLAs changed loyalties.

BJP's most aggressive takeover has been in Arunachal Pradesh. Twice, in 2003 and in 2016, BJP has formed governments in the frontier state without going into elections. As the oldest party in power for much of the time, Congress was the most preferred choice of BJP when it announced the region would be made "Congress-mukt" (Congress-free)".

Of the 93 legislators who have embraced BJP since 2014, 32 (a third) are ex-Congressmen. Much before last month's break-up in Bihar, BJP has been quietly acquiring JD(U) MLAs in the region - six in Arunachal Pradesh in 2019 and five on Friday in Manipur. In recent years, BJP has also opened its doors to legislators from TMC - a relatively new player in the region; as many nine former loyalists of Mamata Banerjee now owe allegiance to BJP's ideologies.

In fact, BJP's first government in the region was not through an election but by engineering a defection of 36 legislators that saw the fall of the governing Congress in 2003. The BJP government led by Gegong Apang, however, lasted just 42 days.

Barring the short-lived exercise in Arunachal Pradesh, BJP lacked much appeal until Narendra Modi arrived on the national scene in 2014 and the northeast became the saffron party's most fertile nursery.

Come 2016, Assam provided BJP the perfect start and just few months before the assembly election, it roped in Himanta Biswa Sarma from Congress, a move that went on to become the biggest game-changer for the saffron party in the region.

Just seven months later, Sarma made his first move to install BJP's second government in the region with a surgical strike in Arunachal that saw the governing Congress fall after it lost 32 of its MLAs in the house of 60 - first to People's Party of Arunachal and finally to BJP in a matter of 48 hours.

The BJP replicated the Assam model in Manipur and before the 2017 election, set its sights on then Congress strongman N. Biren Singh, who was also then CM Ibobi Singh's main challenger. After the election, Manipur, too, fell into BJP's lap.

STATE-WISE

Please also see the Political history pages of individual states. The states listed below are groups of states and not individual states.

North-eastern India

2014-2019

Oct 20, 2022: The Times of India

From: Oct 20, 2022: The Times of India

Home minister Amit Shah’s recent comments in Guwahati that the “real Bharat jodo” was begun in 2014 by PM Modi in the Northeast have refocussed attention on BJP’s political expansion in the region. Shah was there to inaugurate the party’s largest office in the Northeast – the Atal Bihari Vajpayee Bhawan.

His political framing of BJP’s regional push as one of “uniting India or Bharat jodo” vs what he called a narrative of “Northeast todo” (break the Northeast) does follow a major structural shift taking place in regional politics in 2014, where BJP replaced Congress as the region’s dominant national party.

Shah’s Guwahati pitch follows his assertion at BJP’s national executive in Hyderabad in July that the party had now found a “permanent address” in the Northeast. But how robust is this political shift?

Saffronrise: Until 2016, BJP had never been elected to office in any of the eight northeastern states, minus a one-year interlude in Arunachal Pradesh in 2003 when Gegong Apang briefly defected to the party.

Today BJP holds office in six of the region’s eight states.

In four of these – Assam (with wins in 2016 and 2021), Tripura (2018), Arunachal (2016 and 2019) and Manipur (2017 and 2022) – BJP CMs are at the helm.

In Nagaland (2018) and Meghalaya (2018), BJP is a junior coalition partner in alliance governments led by larger regional parties.

In Mizoram and Sikkim, though there are tensions, governing parties are formally still members of the North East Democratic Alliance (NEDA).

Parliamentary polls have also shown a political shift from Congress to BJP. In 2014, BJP had won just 32% Lok Sabha seats in the Northeast. By 2019, its tally went up to 56%.

Onboarding diversity: These poll victories legitimately allowed BJP to claim that it was more than a Hindi-Hindu party.

BJP-governed Assam has the highest proportion of Muslims (34.2%) in any large Indian state after Kashmir.

As much as 87.9% of Nagaland, 74.5% of Meghalaya, 41.2% of Manipur and 30.2% of Arunachal are Christian.

It is this diversity and complexity of the Northeast, so far removed from the politics of the Hindi heartland, that makes BJP’s rise all the more remarkable. For a party perceived as being Hindu-centric, the symbolism of victories in these states is huge.

BJP in the Northeast demonstrated significant strategic adaptability, operating differently in these states, compared to the Hindi heartland.

His political framing of BJP’s regional push as one of “uniting India or Bharat jodo” vs what he called a narrative of “Northeast todo” (break the Northeast) does follow a major structural shift taking place in regional politics in 2014, where BJP replaced Congress as the region’s dominant national party.

How BJP did it

Mergers and acquisitions: Very much like a corporation looking to expand into new areas, BJP focussed on looking at the competition and acquiring as much of the rival talent as possible. Assam CM Himanta Biswa Sarma is both the progenitor and the most famous example of this strategy.

Researching the backgrounds of all BJP ministers in five northeastern states, I found that 50% of all ministers between 2016 and 2020 had earlier served in other parties. In Manipur, this ratio was as high as 80% in favour of defector-ministers. In Meghalaya and Arunachal, it was 100%.

Strategic alliances: State-specific alliances drove BJP growth in each state. For example, in Assam with AGP and BPF in its first government, and then AGP and UPPL; in Manipur with NPP, NPF and LJP; in Meghalaya with UDP, PDF and HSDP; and in Nagaland with NDPP.

Development narrative: When the data scientist Rishabh Srivastava and I tested independent satellite data to see how the region had changed under UPA and NDA governments, we found the changes to be remarkable.

Satellite images showed that nightlight intensity increased across the region. It grew by 80% in Arunachal in the 2014-18 period (compared with 30% in 2009-13), Manipur by 114% (28% in 2009-13), Assam by 50% (33% in 2009-13), Mizoram by 63% (29% in 2009-13), Nagaland by 59% (15% in 2009-13), Sikkim by 41% (28% in 2009-13), and Tripura by 42% (55% in 2009-13).

Central funding increases: Government data shows that central government funding for most states in the region increased significantly between 2014-15 and 2018-19. In Assam, central funding increased by over 50% in this period, in Manipur by over 60% and it more than doubled in Mizoram.

Challenges: BJP faces new headwinds as it gears up for elections in Tripura, Nagaland and Meghalaya in 2023. In Tripura there’s a renewed challenge in the tribal areas from Tipraha Indigenous Progressive Regional Alliance (TIPRA Motha), in Meghalaya there have been tensions within the governing coalition, and in Nagaland, which moved to an all-party unity government, BJP has finalised a seat-sharing arrangement with ally NDPP. How it plays the Northeast political game over the next few months will be crucial in 2024.

The writer is author of The New BJP: Modi and the Making of the World’s Largest Party and Dean, School of Modern Media, UPES.

Telugu states

1984 – 2019

Syed Akbar, April 9, 2024: The Times of India

From: Syed Akbar, April 9, 2024: The Times of India

BJP has won not more than seven of the 42 seats in any of the 10 Lok Sabha elections held in Andhra Pradesh-Telangana since the party was formed in 1980. While it drew nil results in 1989, 1996, 2004 and 2009 Lok Sabha elections, the party sprang a surprise only once by winning seven seats in 1999.

Analysis of data since 1984 LS elections in united Andhra Pradesh and post bifurcation of the state in 2014 — residuary AP (25 seats) and Telangana (17 seats) — reveals that BJP had equal poll strength in Telangana and Andhra regions before the division of the state. But, after the bifurcation, its electoral strength is limited to Telangana.

While BJP secured four seats in Telangana in 2019, it drew a blank in Andhra Pradesh in the first poll held after the division. Interestingly, BJP contested the LS polls in 2019 on its own without any alliances either in Telangana or Andhra. The villainisation of Nizam and Bhagyalakshmi temple issue helped BJP in Telangana in 2019. This time though, it is in alliance with Telugu Desam and Jana Sena in Andhra and going alone in Telangana.

Analysis shows that the Narendra Modi wave helped BJP to some extent in Telangana in 2019, as it won four seats. Earlier, the party also benefited from the wave in 2014 polls (held soon after the bifurcation) in both Andhra and Telangana regions. It won three seats — two in Andhra and one in Telangana.

The only time BJP made it big in LS hustings in the Telugu belt was in 1999 when it won seven seats — three from Andhra and four from Telangana regions. The party benefited from the Kargil wave, coupled with the charisma of Atal Bihari Vajpayee and an alliance with Telugu Desam. Political uncertainty as polls were held within a year of 1998 polls also helped the party.

Historically, BJP opened its account in the region in 1984, the very first general elections it faced, with Hanamakonda in Telangana. Though it drew a blank in 1989, Bandaru Datta- treya manged to win the party one seat — Secunderabad — in 1991. It drew a blank in 1996, but bounced back with four seats in 1998, the second highest number of seats it won in the region. Again in 2009, it drew a blank but won four seats in 2019.

HISTORY, YEAR-WISE

1951-2019: seats won in Lok Sabha

May 24, 2019: The Times of India

From: May 24, 2019: The Times of India

The saffron rise: From 3 seats in first LS election to 303 in 2019

NEW DELHI: Formed in 1951 as the political arm of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Bharatiya Jana Sangh managed to win only 3 seats in the first general elections in 1951-52 — two in West Bengal and one in Rajasthan. Cut to 2019, and BJP, the entity that came into being in 1980, bagged 303 seats on its own establishing itself as India’s undisputed political force and the main claimant to the Centre.

1980- April 2017: milestones

See graphic:

Bhartiya Janata Party, a brief timeline, 1980 onwards...

1980> 2018: the rise

April 6, 2018: The Times of India

From: April 6, 2018: The Times of India

From: April 6, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

The BJP is the world's largest party in terms of primary membership

The party won a significant majority in the 2014 LS polls, winning 282 seats

The Bharatiya Janata Party's (BJP) rise over the past 38 years has been stellar. The party was officially created on April 6, 1980. It emerged from the Jana Sangh, which was formed in 1951 by Shyama Prasad Mookerjee. The Jana Sangh merged with some other parties to form the Janata Party in 1977, after the Emergency imposed by then Congress Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The Janata Party dissolved in 1980 and its members formed the BJP with Atal Bihari Vajpayee as its first president.

Vajpayee moderated the Hindu nationalist stance to gain a wide appeal. The party’s dismal performance in the 1984 general elections, however, led to a a shift in ideology towards a more hardline notion of Hindutva.

HOW IT'S FARED IN THE LOK SABHA

The BJP won a landslide majority in the 2014 general elections, winning 282 seats in the Lok Sabha. With the next elections scheduled for 2019, BJP tacticians know that the magnitude of victory in 2014 may be difficult to replicate. In a bid to get re-elected, the party is likely to focus on its three core strengths - a leader, an ideology and a cadre.

LONGEST SERVING CMs: BJP VS THE REST

The top spots go to CPM leader Jyoti Basu, who held the office for more than two decades from 1977 to 2000 and Pawan Kumar Chamling, CM of Sikkim since 1994 and president of the Sikkim Democratic Front. Left leader Manik Sarkar also served as Tripura CM for four consecutive terms -- from March 1998 to March 2018, stepping down recently after the party lost to the BJP-IPFT alliance.

Others who have held the post for long periods are Gegong Apang, who was Arunachal Pradesh CM from 1980 to 1999 and then again from 2003 to 2007, as well as Lal Thanhawla (Congress) who has been Mizoram CM since December 2008. Previously he was CM from 1984 to 1986 and then from 1989 to 1998.

For the BJP, the mantle of the longest-serving CM goes to Narendra Modi, who before becoming the prime minister was the chief minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014. He’s followed by Raman Singh in Chhattisgarh (since 2003) and Shivraj Singh Chouhan (since 2005) -- both are currently at the helm of their respective states. Elections in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh later this year will be a test of their leadership.

WORLD'S LARGEST PARTY

The BJP has built up its primary membership to about 100 million as of April 2015, according to Wikipedia, a number that would have increased in the last three years. Prior to 2015, the Communist Party of China was considered the largest party in the world.

The swelling numbers are in large measure due to a unique initiative spearheaded by Amit Shah called the“missed call” campaign. Launched in 2014, a person can become a member of the party by giving a missed call on a specific toll-free number. New members have to send their personal details, including address and profession.

Skeptics, however, say the groundswell in membership is not a reliable reflection of the party's actual strength on the ground, and that while PM Modi's popularity and the party's current influence may draw thousands into the fold, their loyalty will remain suspect.

The saffron party has another record it can stake claim to. Its new headquarters on Deen Dayal Upadhyay Marg in New Delhi, spread over 1.70 lakh square feet, is bigger than the office of any political party worldwide, according to Amit Shah.

CURRENT REPRESENTATION IN LOK SABHA

The BJP is the country’s largest political party in terms of representation in Parliament and state assemblies.

The party currently has chief ministers in 15 states -- Arunachal Pradesh, Assam (with Asom Gana Parishad and Bodoland People’s Front), Chhattisgarh, Goa (with Goa Forward Party and Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party), Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand (with All Jharkhand Students Union), Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra (with Shiv Sena), Manipur (with Naga People's Front, National People's Party and Lok Janshakti Party), Rajasthan, Tripura (with Indigenous People's Front of Tripura), Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

The saffron party shares power with other political parties in five states. In these states it is a junior ally - Bihar (with Janata Dal (United), Lok Janshakti Party, Rashtriya Lok Samta Party), Jammu & Kashmir (with Jammu and Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party and Jammu and Kashmir People's Conference), Meghalaya (with National People's Party, United Democratic Party, People's Democratic Front and Hill State People's Democratic Party), Nagaland (with Nationalist Democratic Progressive Party, Janata Dal (United) and National People's Party) and Sikkim (with Sikkim Democratic Front).

ALLIANCE PARTNERS

The BJP has a number of alliances with regional parties under the NDA umbrella (mentioned above).

However,the saffron party has testing relationships with several of them. The Shiv Sena is its oldest ally -- since 1995 when the two parties shared power in Maharashtra. The relationship is, however, on way to being severed with the Sena already announcing it will not have a truck with the BJP for the 2019 Lok Sabha polls

Meanwhile, just last month, the BJP suffered a setback when the TDP pulled out of the NDA, miffed with the party over the issue of special status to Andhra Pradesh. In J&K too, the BJP shares an uneasy relationship with the PDP, with both parties having major ideological differences. In Punjab, although the SAD-BJP alliance has endured, the defeat of the alliance in the 2017 assembly elections could lead to a strain in their relationship.

1980-2022

Armaan Bhatnagar, April 6, 2022: The Times of India

From: Armaan Bhatnagar, April 6, 2022: The Times of India

From: Armaan Bhatnagar, April 6, 2022: The Times of India

From: Armaan Bhatnagar, April 6, 2022: The Times of India

From: Armaan Bhatnagar, April 6, 2022: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: The BJP has witnessed a remarkable rise in Indian politics in just over four decades of existence.

Officially founded on April 6, 1980, the party emerged from the shadows of Jana Sangh, which was formed in 1951 by Shyama Prasad Mookerjee. The Jana Sangh merged with some other parties to form the Janata Party in 1977 after the Emergency imposed by then Congress Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The Janata Party dissolved in 1980 and its members formed the BJP with Atal Bihari Vajpayee as its first president.

42 years later, the BJP has now become the world's largest political party that rules a country of over 1.4 billion people and has governments in as many as 18 states.

On its 42nd foundation day, we look at how BJP expanded its footprint to nearly every corner of India and became the mainstay of Indian politics.

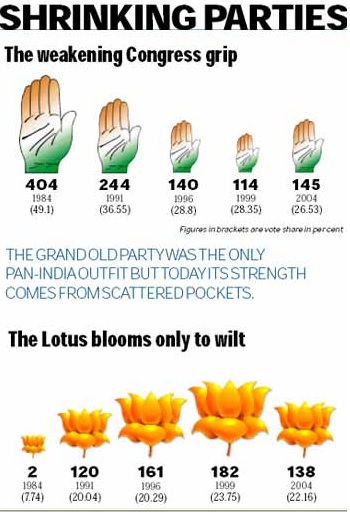

A vault from 2 to 303

In 1984, the BJP contested its first ever Lok Sabha elections as an independent party and opened its account with just two seats, an achievement paled by the Congress's landslide performance in the same year.

But the seminal victory of two BJP leaders — Chandupatla Janga Reddy from Andhra Pradesh and AK Patel from Gujarat — gave the party a much-needed ballast to take on the then mighty Congress in the years to come.

The BJP saw a steady increase in its seat tally in subsequent general election (except in 2004 and 2009). It won 85 seats in 1989 and crossed double digits in 1991.

In 2014 and 2019, the party scripted historic victories under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, securing a comfortable majority in the lower house on its own. In 2019, the BJP crossed the 300-mark on its own for the first time.

Just like its seat share, the BJP also saw a steady rise in its vote share as it cemented itself as the other main national party of India.

In 2014 and 2019, BJP's vote share zoomed past 30%, meaning that 1 in 3 Indians who cast their vote chose BJP. BJP's rise mirrors Congress's decline

As the BJP grew from strength to strength, its principal opponent Congress witnessed a constant decline in state and national elections.

The grand old party, which ruled India for multiple decades, saw its seat share in Lok Sabha dwindle from a high of 415 in 1984 to just 44 in 2014. In 2019, the party managed to secure just 52 seats in the lower house.

The electoral decline of Congress in the previous two Lok Sabha elections is almost inversely proportional to BJP's growth. While the Congress touched a historic low, the BJP scaled the heights of success.

Even at the provincial-level, the BJP is now in power in 18 states — 12 on its own and 6 in coalition. On the other hand, the Congress is left with governments in just Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh.

The chart above shows how the BJP has left Congress far behind across all political parameters.

Dominating both houses

After expanding its footprint across states, the BJP has managed to touch the 100-mark in Rajya Sabha for the first time, becoming the first party since 1990 to cross the threshold.

Although BJP's tally will once again drop below 100 with four of its members retiring in three weeks and 52 seats going to polls, the party has moved within striking distance of its goal of being the first non-Congress party to acquire majority in both Houses.

The BJP's tally, despite way short of majority in the 245-member House, highlights its continuous rise since Prime Minister Narendra Modi led it to its majority in Lok Sabha in the 2014 polls.

The BJP's strength in Rajya Sabha was 55 in 2014 and has since steadily inched up as the party won power in a number of states.

Saffron landscape

Its Lok Sabha victories aside, the BJP has managed to capture power in several states over the last few years. Of the 31 states/UTs in India, the BJP is now in power in 18, including politically crucial states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

The map above shows the BJP's footprint in states it has ruled over the years. The longest ruled among them are Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. In total, the BJP has spent over 25 years in power in Gujarat and 19 years in Madhya Pradesh; albeit not continuously.

The party, however, has failed to make much of a mark in south India. While the BJP has ruled Karnataka for over 7 years over the last few decades, it is yet to form governments in states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana where regional parties hold the sway.

While power has also eluded BJP in West Bengal, the party managed to make impressive gains in last year's assembly elections after an aggressive battle with TMC.

World's largest political party

The BJP's buoyant run in India has turned it into a political juggernaut in recent years.

Today, the saffron party is the largest political outfit in the world with a claimed membership of over 180 million. This is nearly twice the strength of China's Chinese Communist Party, the second largest political party in the world.

Compared to Congress, the BJP has almost ten times the members.

The BJP's organizational strength comes from its vast cadre network, which is spread across the length and breadth of India.

Separately, the party has also undertaken ambitious membership drives in recent years, including initiatives like online enrolment.

The BJP's aggressive membership drives stems from its understanding of maintaining a strong cadre base, which helps it win elections after elections.

1984- 2014: seats in the Lok Sabha

See graphic, ' The Bharatiya Janata Party: seats in the Lok Sabha: 1984-2014 '

1984-2004: Growth across the nation

BJP rides wave to make inroads into new states

The Times of India May 17 2014

BJP's stunning breakthroughs, despite organizational weaknesses and geographical limits, in states like Haryana, Assam, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu speak of the strength of the Modi “lehar“ and provide an opportunity for future consolidation.

BJP leaders were themselves surprised by the response to Narendra Modi in these states where the party has had minimal presence or had atrophied over the years due to organizational neglect.

In Haryana, such was the voter anger against the Hooda government in the state and the Congres regime at the Centre that BJP won 7 seats and 33% of the vote despite some poor candidate selection.

BJP did not go for an alliance with Om Prakash Chautala's INLD due to cases pending against the Jat leader and its pact with Kuldeep Bishnoi's Hayana Janhit Party did not, on paper, command a wide social base. But despite the BJP-Bishnoi pact lacking Jat support, the community voted in large numbers for a `Modi sarkar' ignoring competing claims of Chautala and Hooda.

In fact, the impressive response to Modi's first rally in Rewari after being named BJP's PM candidate set the tone and BJP pulled in votes from almost all sections.

In Assam, as in Haryana with regard to INLD, BJP's decision to avoid an alliance with AGP paid off handsomely . Modi clearly struck a rich vein when he articulated a deep groundswell of resentment against illegal migration and simmering ethno-religious tensions as the seven seats and a 36% vote share indicate.

BJP and its ally PMK won a seat each in Tamil Nadu, riding on its status as the frontrunner. Modi's rallies, despite the language barrier, were well attended and it was the first time since Rajiv Gandhi that a leader from the north became a talking point.

The decision to take on Mamata Banerjee by slamming her “poriborton“ as a sham and raking up the illegal migrants issue was an inspired one as it pitched Modi into the centre of the discourse in West Berngal. The two seats BJP won in the state seem modest, but represent a breakthrough with almost 18% of the votes.

1989 ‘Palampur resolution’

Nov 10, 2019: The Times of India

In 1989, when BJP adopted the Ram temple demand as part of its political plank, the party argued that Congress and other parties were displaying a callous unconcern regarding the sentiments of an overwhelming majority in the country.

“According to all available records, Mughal emperor Babar visited Ayodhya in 1528, destroyed the temple situated at the site believed to be Rama-Janmasthan, and constructed a mosque in its place,” the party said as part of what has came to be known as the “Palampur resolution”. BJP also argued that the conviction that a Ram temple stood at the birthplace of Ram and conflicting claims ould not be settled by a court of law.

The party’s decision to adopt VHP’s demand and back the litigation of Hindu parties seeking restoration of the disputed site as a temple proved to a significant decision, which helped it move to political centre-stage and take on the Nehruvian-Left intellectual consensus on “secularism”. The dispute has finally been settled by a court of law, and the party did amend its position on this. But in the meanwhile, it was able to project the Ram temple demand as an “expression of national sentiment” and attacked its opponents as “Babri parties”, a connotation with a polarising undertone that worked electorally.

The campaign for the Ram temple proved confrontational, with Hindutva proponents’ claim to the historicity of the Ram Mandir disputed by leading academics, most of them with Left orientation. The demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 put BJP in the doghouse and it failed to attract political partners, despite emerging as the single largest party in 1996. But as it grew, it attracted allies like JD(U) which had a score to settle with RJD.

1990-16: BJP emerges all across India

1999: Pawar, BSP voted against the Vajpayee government

The Times of India, Dec 13 2015

Pawar advised Maya to vote against BJP govt in 1999

It is well known that the vote cast by five MPs of Bahujan Samaj Party brought down the Vajpayee government in 1999. But all these years, there has been speculation about the reason the Dalit outfit voted against the man widely credited with making Mayawati the CM of UP for the first time after the State Guest House assault case.

Sharad Pawar has now said that he was the trigger, having persuaded the Dalit czarina that a vote against the government would benefit her politically . He has made the revelation in his just-released autobiography “On My Terms“.

A confidence vote was brought in Lok Sabha after AIADMK withdrew its support to the BJP-led government in April 1999. As the Speaker called for a division of votes, the parliamentary staff took some time to close the doors and activate the voting system, enough for Pawar to have a quick chat with Mayawati. The Vajpayee government lost by one vote.“Those who had noticed me talking to Mayawati before the voting pressed me to clarify,“ he says.

The NCP boss says he is still asked about that brief chat ahead of the voting. “Let me put it this way: I just impressed upon her that the BSP's interests in UP would be served better if she voted against the Vajpayee govern ment,“ he has revealed.

Importantly , Pawar has confirmed that PM Narasim ha Rao rejected a proposal for conducting a nuclear test in view of possible global reac tion. Pawar, as defence minis ter in 1991-92, was told by ad visors to the ministry tha the country was fully equipped to conduct nuke tests to establish it as a nucle ar power. As they pressed for tests, he took the file to Rao for a decision. “After going through the file, he rejected the advice, which I though was the correct decision in the circumstances that pre vailed then,“ Pawar notes.

He says the national econ omy was in a shambles when Congress government took over and Rao did not wan any global reaction to impede the reforms.

2014 LS elections: BJP defies four historical, electoral 'boundaries' with landslide

Milan Vaishnav

The Times of India| May 17, 2014

The 2014 elections have only just ended but analysts are already struggling to comprehend how the BJP's stunning electoral success, deemed unlikely just one year ago, came to pass. The results of India's sixteenth general election challenge our common understanding of contemporary Indian electoral politics in at least four ways.

'BJP can't go beyond its traditional strongholds'

First, the conventional wisdom was that the BJP was trapped by its traditional political and geographic boundaries, deemed insurmountable thanks to the party's Hindutva agenda. Yet, the BJP has garnered an estimated one-third of the all-India vote, a massive improvement from 19% in 2009 and its all-time best of 26% in 1998. This improvement was driven by sizeable vote swings in critical Hindi heartland states as well as smaller but significant gains in the South and East, neither an area of traditional strength. These gains were possible thanks to Modi's persistent focus — in the national theatre of politics — on development and economic mobility. This message aligned perfectly with the issues vexing most Indian voters; a post-poll conducted by CSDS found that in every state surveyed, voters identified development, inflation or corruption as their most important election issue. To be clear, the BJP's saffron agenda has not vanished; recent campaign rhetoric and the party's manifesto confirm this. Yet, going forward, deviation from the focus on governance and development could imperil these newfound gains.

'It can't stitch up alliances better than Congress'

A second assumption that was upturned in this election was that Congres, not the BJP, had the advantage in alliance formation. Despite all the talk about its off-key "India Shining" mantra sinking the BJP in 2004, their loss was more about the BJP's inability to forge the right alliances. This fed doubts about whether the BJP could construct effective alliances in 2014, especially with Modi at the helm. Yet it was a Modi-led BJP that struck key deals over the past several months while the Congres, in contrast, was viewed as a sinking ship. Many observers dismissed the BJP's alliance with the Lok Jan Shakti Party in Bihar, the Telugu Desam Party in Andhra Pradesh, and the Haryana Janhit Congres as trivial. But such criticism overlooked the importance of small shifts in vote share in a fragmented, first-past-the-post electoral system.

'Support for regional parties is growing'

A third assumption underpinning Indian elections since 1989 has been the growth of regional parties. Between 1996 and 2009, the non-Congres, non-BJP share of the vote has hovered around 50%, rising to a record 53% in 2009. The 2014 election, though, saw a decline in regional party support; their nation-wide vote share dipped to roughly 47%, reversing the prevailing trend. Two players merit special attention here. The first is the evisceration of the BSP. Mayawati may draw a blank in Uttar Pradesh while the hard-fought inroads she made in other Hindi heartland states simply evaporated. The second is the weakening of the Left. At a time of rising inequality and concerns over crony capitalism, the conditions would seem propitious for a Leftist revival; instead we are witnessing their collapse.

'Lok Sabha polls are a sum of state verdicts'

A fourth assumption has been that national elections are best understood as an aggregation of state verdicts. The 2014 election outcome, however, is a partial reversal of "derivative" national elections. Not only was this election marked by presidential overtones, but the animating issues—namely, the slumping economy—have also been pan-Indian. Despite this apparent shift, there are two caveats to the "nationalization" thesis.

First, states still remain the most important tier of government for ordinary Indians. This is reflected in the fact that, notwithstanding the record voter turnout in these Lok Sabha polls, turnout for state elections is still 4.5% higher, on average, in any given state. Second, much of the south remained resistant to the BJP's charms. Although the BJP picked up new seats in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu, its advances were limited and much smaller than in the north.

(The writer is an associate with the South Asia programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC)

2015

The Times of India, November 11, 2015

Saffron group also lost big chunk of its own base

BJP's analysis of its de feat in Bihar, accord ing to what finance minister and senior partyman Arun Jaitley told the media on Monday , is that the Maha Gathbandhan's arithmetic beat NDA's chemistry. The data shows that while the first part of that analysis is correct, the second part is not and that NDA flunked the chemistry paper as well. That's revealed by the sizeable fall in NDA's vote share from 2014. The arithmetic was simple enough. In 2014, NDA totalled a vote share of 38.8% of all the votes polled in Bihar, including those for NOTA. JD (U) polled 15.8%, RJD 20.1% and Congress 8.4%. Had the three been together, their combined vote share of 44.3% would have been well over NDA's and the results would thus have been quite differ ent. The formation of Maha Gathbandhan manifested the recognition of this reality by the three parties.

Jaitley was referring to the fact that the arithmetic addition of the vote bases of the three parties did happen, contrary to NDA's expectations. He was right.

Maha Gathbandhan's vote share in these polls was 41.9%. Considering that Jitan Ram Manjhi's HAM(S) had broken away from JD(U) between the 2014 and 2015 polls and had won 2.3% of the votes polled, what this meant was that the grand alliance succeeded in keeping the rest of its votes together and transferring them to each other, no mean achievement.

Now for the chemistry. NDA 's vote share in the elections just concluded was 34.1%, or 4.7 percentage points lower than in 2014.

This despite the addition of the HAM(S) votes to its kitty . Exclude the fledgling party and BJP , Paswan's LJP and Upendra Kushwaha's RLSP polled just 31.8% of the votes, a drop of seven percentage points from 2014. That's not down to Maha Gathbandhan arithmetic, it shows a disenchantment with NDA among voters.

BJP's vote share was itself five percentage points lower than in 2014. The party could legitimately point out that this is an unfair comparison because it contested 182 of the assembly segments in the Lok Sabha elections and only 157 this time. So, we looked at only those segments in which it was in the contest in both 2014 and 2015 and the analysis still shows a significant drop in vote share for BJP .

There were 129 assembly constituencies in which BJP was in the contest in both elections. Its share of votes in these segments in 2014 was 39.9%. This time round, it was 37.7%, a swing of over two percentage points away from the party . Remember also that unlike in 2014, supporters of Manjhi should also have voted for BJP candidates in these seats thereby boosting its share beyond 40% if it had held on to its own votes.

Actually , BJP polled even in absolute terms nearly 87,000 fewer votes in these 129 seats than it did in 2014. This at a time when the total votes polled in these seats rose by almost 11.1 lakh. In short, while the votes polled rose on average by over 8,500 per seat, BJP's votes fell by about 700 per seat.

That points to a failure of its own chemistry , not just a success of Maha Gathbandhan arithmetic. What made matters worse was that its allies lost their chemistry even more drastically .

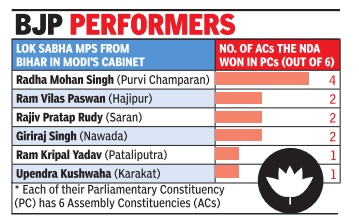

2015, Bihar elections: performance in Union ministers’ strongholds

The Times of India, Nov 10 2015

Vishwa Mohan

NDA fares poorly in stronghold of Union ministers from Bihar

BJP and its allies found the going tough in the Lok Sabha seats represented by their Union ministers with only agriculture minister Radha Mohan Singh's constituency Purvi Champaran returning a decent number of MLAs. In Purvi Champaran, the NDA won four out of six assembly segments. Three -Motihari, Kalyanpur and Pipra -of these were won by BJP while Govindganj went in favour of ally LJP .

Purvi Champaran also emerged as the best performing district for the BJP-led alliance in Bihar. The NDA won eight out of 12 assembly seats in the district. Singh, a veteran BJP member from the state, has been in the Mo di Cabinet since May 2014.

Upendra Kushwaha and Ram Kripal Yadav turned out to be the worst performers, winning only one seat each rom their respective constituencies of Karakat and Pataliputra. Kushwaha, minister of state for HRD, is the chief of the Rashtriya Lok Samata Party , which had fielded 23 candidates across the state.The party was victorious on only two of these seats.

Yadav, a former RJD member, joined BJP before the 2014 parliamentary elections. He represents Pataliputra in the Lok Sabha and is minister of state for drinking water and sanitation in the Modi Cabinet. Except for Danapur assembly segment in his parliamentary constituency , all five went in favour of the Grand Alliance.

Besides these three, Ram Vilas Paswan, Rajiv Pratap Rudy and Giriraj Singh are the other Lok Sabha MPs in the Union Cabinet. Though there are two more ministers from Bihar (Ravi Shankar Prasad and Dharmendra Pradhan), these two represent the state in the Rajya Sabha.Pradhan, petroleum minister, is from Odisha but represents Bihar in the upper House.

Rudy , MP from Saran and minister of state (independent charge) for skill development and parliamentary affairs, could win only two out of six seats for the NDA. Similarly, Hajipur MP Paswan and Nawada MP Giriraj Singh won two seats each for the BJP-led alliance.

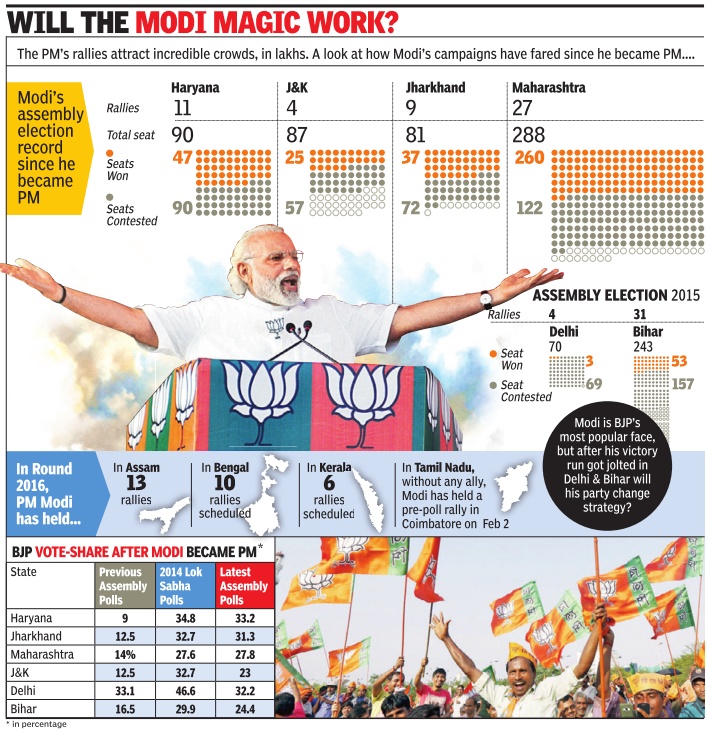

2016: Assam, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Wesr Bengal

See graphics

'Seats and vote share of BJP, 2011 and 2016, Assam, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal'

and

'Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s election rallies for the state assembly elections of 2014 and 2015, and their impact

The Bjp’s vote share after Narendra Modi became Prime Minister'

The Bjp’s vote share after Narendra Modi became Prime Minister ; Graphic courtesy: The Times of India, April 23, 2016

2017 vis-a-vis 2012

How the BJP won state assemblies

From December 19, 2017:The Times of India

See graphic:

How the BJP won state assemblies between 2012 and 2017

Performance in state assembly elections

See graphic, ‘How BJP's seats and vote share in 2017 compare with 2012 seats’

2018

BJP overcomes ‘church veto’ in Nagaland, Meghalaya

March 4, 2018: The Times of India

In a region where religious organisations have had a role in elections, the contest in Nagaland and Meghalaya became sharper still with church groups calling for resistance against a “Hindutva” invasion of the north-east and BJP-R-S-S launching their most determined bid yet to wrest power.

In a strange inversion, there was no talk of beef in the campaign as BJP sidestepped the issue, arguing that it was not against local customs and traditions. In fact, its local leaders in Nagaland made it a point to say they were Christians too and any talk of cultural aggression was misplaced. In the end, BJP is set to be in office in Nagaland and could be a partner in Meghalaya.

Congress projected BJP as “anti-minority” and said regional outfits like NPP were likely to forge an alliance with the saffron party. The call didn’t deter voters from backing NPP, and BJP is likely to extend it support to form the government in Meghalaya.

The clash of faiths lies at a deeper plane. BJP-R-S-S is looking to weave a political and cultural narrative that seeks to incorporate the north-east in the Hindu nationalist “mainstream”, arousing identity politics of small parties and the rejection of Hindutva by church groups. The view that the north-east is brimming with “sub-nationalities” is anathema to BJP which has, nonetheless, moved to accommodate local traditions.

Winning the north-east is important for BJP as the party looks to counter the “church veto” and present itself as an inclusive political organisation with no geography out of reach due to demographics.

It made the point strongly in Assam in 2016 when Congress’s wooing of the Muslim vote could not prevent a saffron landslide.

A potent mix of Hindutva-laced nationalism, development promises and a stand against illegal migrants from Bangladesh has worked for BJP in the northeast, helped also by the work of Sangh organisations, which see the battle in terms of “saving” the northeast from demographic invasion and maximising its advantage through the projection of PM Narendra Modi.

There was no talk of beef in the campaign as BJP side-stepped the issue, arguing that it was not against local customs and traditions

Himanta Biswa Sarma’s work in the NE

Prabin Kalita, Out of Cong, now BJP’s kingmaker, March 4, 2018: The Times of India

From: Prabin Kalita, Out of Cong, now BJP’s kingmaker, March 4, 2018: The Times of India

BJP’s poll formula, combining organisational strength and foolproof alliance equations, has proved successful. Leading the march in the north-east is Himanta Biswa Sarma.

A former Congressman, the 48-year-old Assam minister crossed over to BJP in 2015 a few months before the state went to the polls. The saffron party came to power in the north-east for the first time and has not looked back since. The North-East Democratic Alliance (Neda) — formed with the objective of creating a “Congress-mukt north-east” — was the first step towards BJP’s expansion goal. Sarma is its convener and has been responsible for arriving at the understandings that have favoured BJP’s growth. He made a mark as kingmaker in Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur and, now, Tripura.

Having seen to BJP’s victory in Tripura, Sarma rushed to Shillong in the afternoon. With Meghalaya having a hung House, Sarma has taken his position on the battleground to ensure that a Congress gover nment does not come to pass.

Sarma’s modus operandi is clear — break the rival and win its key leaders over to BJP. Like him, Manipur CM Biren Singh and Arunachal Pradesh’s Pema Khandu were Congress leaders before. “The influence of BJP was quite limited in the north-east. Unless new people joined, it couldn’t have grown in strength,” he said.

He attributed BJP’s growth in the north-east to PM Modi’s development agenda. “For the first time, people have seen development at the local level. They have seen the huge investment by the government in rail, road and air connectivity,” he said. Striking the right alliance at the right time was critical. “BJP’s structure has been strengthened. Under Neda, a lot of regional parties have joined us,” he added.

2019

From: May 24, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

BJP, Vote share: 2014 vis-à-vis 2019

2019: Women’s contribution to BJP’s victory

Rajeshwari Deshpande, July 18, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rajeshwari Deshpande, July 18, 2019: The Times of India

Discussion on women’s empowerment in Indian politics was revived during these elections in the wake of the gradual increase in women’s turnout in state assembly elections over the past few years and the closing of the gender gap in turnout. Although slogans like ‘beti bachao, beti padhao’ have remained blemished by the growing social insecurities for women, political parties tried to outdo each other in attracting women voters.

More substantial interventions came from regional parties like BJD and TMC when they reserved candidatures for women. This strategy paid off when the highest ever number of women MPs entered the Lok Sabha this time. If ‘winning women’ constituted one part of the arrival of women’s constituency in the 2019 elections, the distinctive nature of women’s vote must be seen as the other important, though neglected part of the story.

What do we know about women’s voting patterns in Indian elections? Given the layered nature of gender realities in India, do women always vote as women? The National Election Studies conducted by the Lokniti group may help us answer such questions in a more nuanced way. These data sets track the Indian elections since 1996 and they indicate some long term trends regarding the nature of women’s vote. The first is about gender advantage to Congress among women voters. In most Lok Sabha elections since 1996 the party enjoyed slightly higher support among women than among men at the all India level.