Bhoi-Bestas: Deccan

Contents[hide] |

Bhoi-Bestas

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Origin

The Bestas, also called Parkitiwaru, are "mostly to be found in the Telugu Districts adjoining the Madras Presi- dency. The origin of their name is obscure. Some derive it from the Persian "Behishti," but this derivation seems to be fanciful. The Bestas claim to be descended from Suti, the great expounder of the Mahabharata. Another legend traces their des- cent to Santan, the father of Bhisma by Ganga. These traditions, of course, throw no light upon the origin of the sub-caste. Their physical characteristics tend to mark them as Dravidians.

Marriage

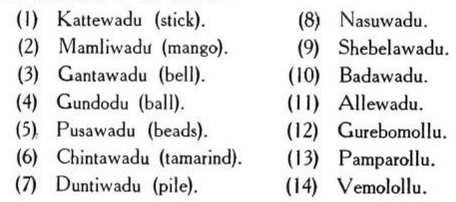

The Bestas profess to belong to, one gotra, Achantraya, which is obviously inoperative in the regulation of their matrimonial alliances. Their marriages are governed by a system of exogamy consisting of family names. The following are some of the typical surnames of the caste : —

The exogamous sections are modelled on those of the other Telugu castes. The Bestas forbid a man to marry a woman of his own section. No other section is a bar to marriage, provided he does not marry his aunt, his niece, or any of his first cousins except the daughter of his maternal uncle. A man may marry two sisters, or two brothers may many two sisters, the elder marrying the elder sister and the younger marrying the younger. Outsiders are not admitted into the caste. Besta girls are married before they have attamed the age of puberty ; but sometimes, owing to the poverty of her parents, a girl's marriage is delayed till after the age of puberty. Girls are not devoted to temples, or married to deities. Should a girl become pregnant before marriage, her fault is condoned by her marriage with her lover, a fine being imposed upon her parents by the caste Panchasat. Sexual indiscretion with an outsider is punished by expulsion from the caste. Conjugal relations commence even before the girl attains puberty, provided a special ceremony is per- formed on the occasion. A Besta girl on attaining puberty is ceremonially unclean for five days. Polygamy is recognised theore- tically to any limit, but is practically confined to two wives.

The marriage ceremony is of the orthodox type and closely corresponds to that in vogue among other Telugu castes of the same social standing. It takes place at the girl's house, under a booth made of eleven posts. The central post, muhurta medha, consists of a gukr branch (Ficus indicus) and is topped with a lamp which remains burning throughout the ceremony. The marriage procession is made on horseback. " A Brahman is employed as priest to conduct the wedding service. Kanyadan, or the formal gift of the bride, by her parents, to the bridegroom, is deemed to be the essential portion of the ceremony. " In the nagbali, which is celebrated on the fourth day after the wedding, the bridegroom, with a net in his hand, and the bride, with a bamboo basket, walk five times, round the polu. The panpu which follows is very interesting as, therein, the young couple are made to enact a pantomimic drama of married life. The final ceremonial is Wadihiyam, by which the bride is sent to her husband's house. The bride-price, varying in amount from Rs. 9 to Rs12, is paid to the girl's parents.

Widow-Marriage & Divorce

Widow marriage (Mar-mannu) is in vogue. The widow is not restricted in her choice of a second husband, save that she is not allowed to marry her late husband's younger or elder brother, nor any one who belongs to her husband's or her father's section. The sons of a widow are admitted to all the privileges enjoyed by the sons of a virgin wife. The ceremony is performed on a dark night, the widow bride being previously presented with a sari and choli and a sum of Rs 5/4 for the purchase of bangles. A woman may be divorced on the ground of unchastity, the divorce being effected by the expulsion of the woman from the house, a little salt having been previously tied in her apron and the end of her garment having been removed from off her head. A divorced woman is allowed to marry again by the same rite as a widow, on condition, however, that her second husband refunds to her first husband, half the experses of her marriage as a spinster.

Inheritance

The Bestas follow the'Hindu law of inheritance. A sister's son, if made a son-in-law, is entitled to inherit his father- in-law's property, provided the latter dies without issue and the former performs his funeral obsequies. It is said that the eldest son gets an extra share, or jethanga, consisting of one bullock and Rs. 25.

Religion

The religion of the Bestas is a mixture of animism and orthodox Hinduism. They are divided, like other lower Telugu castes, between Vibhutidharis or Saivas, who follow the tenets of Aradhi Brahmans, and Tirmanidharis or Vaishanavas, who acknow- ledge Ayyawars as their gurus.

Their tutelary deity is Vyankatram, worshipped every Saturday with offerings of sweetmeats and flowers, but the favourite and charac- teristic deity of the Bestas is Ganga, or the river goddess, worshipped by the whole caste, men, women and children, in the month of Ashada (July- August), when the rivers and streams are flodded. The puja is done on the evening of the Thursday or Monday sub- sequent to the bursting of the monsoons. The elders of the caste officiate as priests. They observe a fast during the day, and at about five in the evening resort to a place on the bank of a river at some distance from the village. A piece of ground is smeared over with cow-dung and four, devices representing, respectively, a crocodile, a fish, a tortoise and a female figure of Mari Mata (the goddess presiding over cholera), are drawn upon the ground over which sand has previously been strewn. These devices are profusedly covered with flowers, kunkvm, turmeric powder and powdered limestone. In front of the figure of Mari Mata is placed a large bamboo tray, containing a square pan made of wheaten flour and a turmeric effigy of Gouramma. The flour pan is filled with six pounds of ghi, in which are lighted five lamps, one in the centre and one at each of the four corners. In front of Gour- amma, and in the pan, are placed six bangles, a piece of cocoanut, a bodice, four annas, some areca nuts, betel-leaves, catechu and chunam. The bamboo tray is then rested on a wooden frame made of four pieces of pmgra wood (Erythrina indica), each two feet in length, and furnished with handles of split bamboo. After the worship is over, the priests, and as many of the male members as are able to touch the bamboo tray, lift it with the wooden frame and carry the .whole into the flooded river, plungmg into the water sometimes neck

deep. After shendi (the fermented juice of the wild date palm) has been sprinkled on all sides, the bamboo tray is thrown into the flood to be floated away by the current. After the distribution of Prasad the multitude disperse. Women are not allowed to touch the goddess. At the Dassera festival the Bestas worship their nets, which they always regard with extreme reverence. When epidemics of cholera and smallpox break out, the Bestas make animal offerings to the Mari Mata or Pochamma. Brahmans are employed for the worship of the great gods of the Hindu pantheon.

Disposal of the Dead

The Bestas bum their dead, with the head pointma to the south, but persons dying before marriage are buried. Women dying during childbirth are burned. The ashes are collected on the third day after cremation and thrown into the nearest stream. Married agnates are mourned for eleven days : the unmarried for five days only. Relations are fed on the 11th day after death. On the Mahalaya day, rice, ghi and some money are offered to a Brahman in the name of the deceased ancestor. Ayyawars, in the event of the deceased being a Tirmani- dhari, and Jangams, should he be a Vibhutidhari, attend the funeral ceremonies.

Social Status

Socially, the Bestas rank above the Dhobi, Hajam, Waddar, Yerkala and lower unclean classes. Their social status is equal to that of the Mutrasis. They do not eat food cooked by a Jingar or a Panchadayi but will do so from the hands of the Mutrasi, Golla, Kapu Kurma and other castes of equal social standing. As far as their diet is concerned, they eat fowl, fish, mutton and the flesh of the crocodile, tortoise and lizard, but abstain from pork. They indulge fremented- in fermented and distilled liquors. They do not eat the leavings of other castes.

Occupation

The, original occupation of the caste is fishing and palanquin bearing, but many of the members are engaged as domestic servants in Muhammadan and Hindu houses. A curious custom that prevails among them is that, when employed as palanquin bearers, they have their food cooked in one place, sharing equally the expenditure incurred thereon : at the time of meals the cooked food must be divided into exactly equal portions among the members, no matter what, their ages may be. Some of the Bestas have of late years taken to cultivation as 2 means of livelihood.