Bihar castes

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

Caste in modern history

Arjun Sengupta, Oct 6, 2023: The Indian Express

I. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

What was the caste landscape in Bihar like historically?

Historically speaking, Bhumihars, Brahmins, Rajputs and Lalas (Kayasthas) have together dominated Bihar’s political and caste landscape. They were the major landowners, and until the 1970s, their dominance was largely unchallenged. Most prominent Bihari leaders till date have come from either these four castes, or from the “powerful backwards” — comprising the numerically sizable castes of the Yadavs, Koeris (Kushwahas), and Kurmis.

What changed in the late 1970s?

First, a backward caste (Nai) leader called Karpoori Thakur (1924-88) became Chief Minister in June 1977. (He was in the post for a few months earlier in 1970-71.) This can be seen as a culmination of a process that began in the late 1960s, when, for the first time, a large number of backward caste members entered the Bihar Vidhan Sabha. In 1978, Thakur implemented, for the first time, a model of layered reservation, in which a 26% quota was divided into 12% for backwards, 8% for the poor among the backwards, 3% for women, and 3% for the “upper caste” poor. Thakur is considered to be the mentor of Lalu Prasad and Nitish Kumar.

Second, the movement led by Jayaprakash (JP) Narayan (1902-79) catalysed the arrival of charismatic student leaders — Lalu, Nitish, Ram Vilas Paswan, Sushil Kumar Modi, Ravi Shankar Prasad — who would go on to reshape the politics of Bihar in the 90s.

What role did Lalu have in the story of caste in Bihar?

The arrival of Lalu in the 1990s was a seminal moment for caste relations. He directly challenged the political power of the four “upper” castes; his provocative slogan was “Bhura baal (Bhumihar-Rajput-Brahman-Lala) saaf karo”.

Anthropologist Jeffrey L Witsoe argued that Lalu transformed caste relationships by challenging the entrenched power of the upper castes in the bureaucracy and all elite domains, and empowering local elected leaders, often from the backward castes or Muslims. Yadav’s rule created historic social churning and, in many places, transformed the social relations between backward and upper castes. However, he “prioritised democracy over development”, Witsoe said, which meant that the state as a whole may have suffered in some ways.

The 1990s saw a collapse of law and order, and massive corruption, and, while the rest of the country was beginning to grow quickly, Bihar stagnated as a whole. The Lalu years were the fire that scorched the caste society of Bihar, but one could argue it burnt parts of the forest down too.

How did the implementation of the Mandal Commission report impact caste consciousness?

In Bihar, even today and much more 40 years ago, a government job was the lottery ticket to progress for most families. It was hoped that reservations would fundamentally transform the lives of many.

The Mandal recommendations further strengthened the already strong caste consciousness among the OBCs. Someone like Karpoori Thakur was a big leader long before the Mandal discourse even began, and the student leaders from backward castes were already influential by the time Mandal came. What Mandal also managed to do was to solidify the bonds between the upper-castes as they came together to oppose the reservations.

How did things change with Nitish?

Nitish understood that Yadavs and Muslims were firmly with Lalu, but upper castes, Dalits, and lower backwards (EBCs) could be wooed for votes. So he brought in policies to target the EBCs and a section of Dalits. For instance, for the first time in Bihar’s history, he implemented reservation in local political positions, not just for women and Dalits, but also for the EBCs — backwards who have now emerged as the most populous caste group in the caste survey — and brought targeted policies for this group.

He also understood that within the Scheduled Caste groups, a few were better off than the rest — the Paswans, for instance, were historically bodyguards of powerful landlords, and shared a reasonably good relationship with the feudal powers, but this was not the case for lower Dalits such as Majhis or Doms. So he carved out a separate “Mahadalit” group from the Dalits, created a Mahadalit Vikas Mission in 2007 and pushed a separate set of policies that discriminated in favour of these Dalit groups. When it came to picking a successor, Nitish Kumar and the JDU picked Jitan Ram Manjhi as the first Mahadalit Chief Minister of Bihar for nine months in 2014-15.

II. EBCs AND CASTE SURVEY

How do EBCs differ from other OBCs?

Extremely Backward Classes are the most populous caste group in Bihar — 36% — as per the recent survey. The fundamental disparity between them and the powerful backwards is with regard to land ownership, which puts them at a major disadvantage.

The bottom jatis in terms of asset ownership in the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) of 2011 are all Dalits, but many of the jatis immediately above them are EBCs. So not only are EBCs lower than other OBCs in the land-owning and caste hierarchies, but even in the wealth hierarchy, they are near the bottom.

Since OBC reservations is a single category, a lot of the benefit is garnered by the powerful backwards who, according to the survey, constitute 27% of the state’s population, significantly less than the EBCs. Nitish and Karpoori Thakur recognised this and introduced targeted policies, now there are numbers to back that assessment.

If the layers within the OBCs have been known since the 1970s, how does just having numbers help?

EBCs are fundamentally different from the powerful backwards, and putting them in the amorphous OBC category does them a big disservice as they remain at the bottom of the hierarchy. It is the same with the Dalits and Mahadalits. If some groups require more help than others, it is crucial to have data on them — at the very least, it allows the groups to make legitimate claims for themselves.

Our work in Bihar has shown that having a Dalit Panchayat president significantly improves outcomes — from asset ownership to political participation — for Dalit members in the community in the long run. Bihar has more than 130 million people and, if it were a country, it would be the 10th largest in the world. The backwards and EBCs are 27% and 36% of this large mass of people — from a global perspective, we might be talking about whole countries. For instance, EBCs in Bihar alone are four times the population of Sweden.

Also, the survey could also help us understand how caste functions within Muslim society, in addition to shedding light on the relative well-being of Muslims vis-a-vis Hindus.

How does having data translate to better-designed policies on the ground?

Here is an example, staying with local governance: reservations for Dalits for the post of Panchayat mukhiya (president) is based on the proportion of Dalits in a particular block (comprising 15 Gram Panchayats). If 20% of people in a block are Dalits, 20% of GP mukhiyas will be Dalit as well. While there has been similar reservation for EBCs at the Panchayat level, the proportion of EBCs in a block was not known — so the government made a rule that up to 20% of seats can be reserved for EBCs.

Now, with this survey, the government has granular jati data at a very fine geographical level, and the caste survey can rationalise policies such as this. And such policies can have serious knock-on effects on governance down the line.

So the data are known, what happens now?

Beyond parties making claims for more reservation, it is unlikely much will change in the short term. The government will need to spend time number-crunching and designing policies before we see well-tailored programmes on the ground. Nothing dramatic should be expected before, at the earliest, the Lok Sabha elections next year.

Also, all this is conditional on the data being good — and we have no idea about that yet — and the government having the political will and administrative nous to follow through. Not much is known about the specifics of how the data were collected and rationalised, etc.

Critics have said the survey results will lead to intensified jockeying for reservations and potentially social turmoil. If the data allow certain jatis who are extra marginalised within a marginalised population to make legitimate claims for their rights, I am all for it.

Also, I am not sure jostling for reservations is necessarily bad for society. A lot of jostling is already happening at the baseline. And if reservations do cross the 50% mark (as prescribed by the Supreme Court in Indra Sawhney), that may not necessarily be a bad thing. Tamil Nadu has reservations for up to 70% of the population and it is not going through turmoil as a consequence.

III. POLITICS AND IMPLICATIONS

What was the need to have this survey — and in Bihar specifically?

The survey was proposed by the JD(U), and part of the reason was it needed some rejuvenation.

Nitish does not have a strong caste base — even this survey shows that his caste, Kurmis, are under 3% of the population. He needs more castes to rally behind him, and the cynical view is the survey was born out of Nitish’s personal politics.

But also, the proponents of the survey — Nitish and Lalu — emerged from the JP movement, and their politics can be traced back farther to the socialism of Ram Manohar Lohia, whose social justice polemics would argue for better enumeration and therefore better representation of castes.

The SECC data, gathered at the national level, was not released for various reasons. But the Indian government has considered obtaining jati data at the local level for at least three decades now.

On why Bihar rather than, say, Uttar Pradesh — maybe it is just that Lalu and Nitish are now together and can push for something they agree on. Maybe if Nitish was still with the BJP, things would be different. But there is no way to say for sure. Bihar does have a history of powerful backwards in politics in a way that UP does not, though.

Why is BJP leadership opposed to the survey?

The BJP’s position is guided by its goal of maintaining Hindu unity, and it would be opposed to anything with the potential to divide Hindus. One of the reasons behind Narendra Modi’s electoral success is the consolidation of the Hindu vote — which means that he has managed to make OBCs and Dalits vote for the BJP as Hindus first, rather than as members of their castes.

It is important to underline though that the opposition to the survey comes from the central BJP, not the party’s Bihar unit. The BJP in Bihar has a much broader base, with many EBCs within the party fold and Dalis offering support too.

Could this be a Mandal 2.0 moment as some JD(U) and RJD leaders have claimed?

The survey results will act as a driver for the kind of politics these parties have always done. The data, if it is any good, will add weight and strength to their demands, and will help them make targeted policies for their base. Most parties in the INDIA alliance will make demands for the backwards. And yet, it may not be a gamechanger, especially for the coming elections. The invocation of Mandal is purely political. But it can definitely be the starting point for something bigger in the longer run.

Mandal was transformational because it, for the first time, took an entire mass of people and recognised their marginal position and gave them reservations. Anything that comes next will build on top of it and hence bring marginal change. The caste survey is great for policy and for a certain kind of politics, but comparing it to Mandal misses just how enormous Mandal itself was for the country.

MR Sharan is an Assistant Professor teaching economics at the University of Maryland, College Park. His research, mostly set in Bihar, focuses on local governments, with an emphasis on policy innovations that could empower marginalised groups. His book on Bihar, titled ‘Last Among Equals: Power, Caste and Politics in Bihar’s Villages’ was released in December 2021.

1931 vis-à-vis 2021: Chinmay Tumbe’s analysis

From: Twitter.com

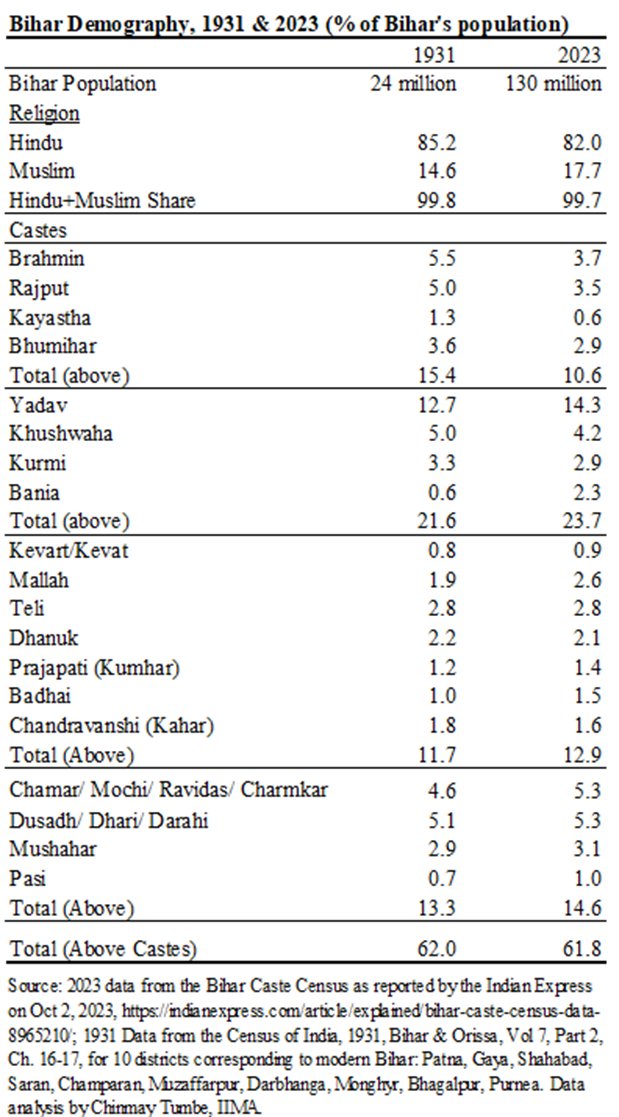

The 2023 Caste Census of Bihar allows us to see century-long demographic change in castes for a sizeable Indian region for the first time.

This thread compares the Bihar Census of 1931 with 2023 and reveals: Broad stability+ The significance of migration selectivity.

The 2023 survey: Results

A

Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

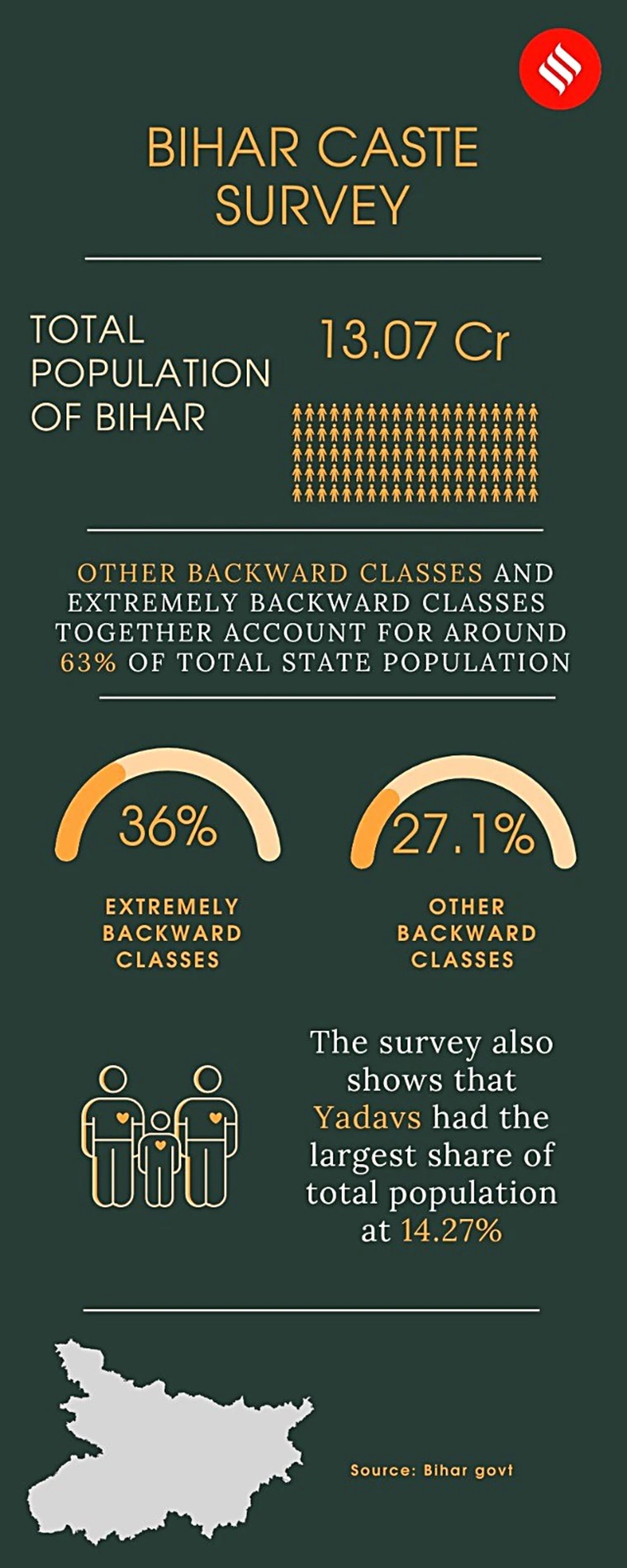

The caste survey data released by the Bihar government Monday shows that at 36.01%, EBCs or Extremely Backward Classes form the largest chunk of the state’s population, followed by OBCs at 27.12%, SCs at 19.65%, general population at 15.52% and STs at 1.68%. A look at the ticket distribution in the last Assembly elections shows the EBCs ranked high on the priority list of all parties.

Nearly a quarter of the candidates in the RJD and JD(U) lists, 24% and 26% respectively, belonged to EBCs, at a time when their numbers – in the absence of a census – were estimated at about 25% of the state population.

Considered floating voters, they have always been wooed by all parties.

Of the 144 candidates the RJD fielded in 2020, as a part of the Mahagathbandhan, the Yadavs, comprised 40% (58) and Muslims 12% (17) of the candidates – the two being the bedrock of the party’s MY plank.

The caste survey data put out put Yadav numbers at 14.27% of the population.

The NDA fielded 23 Yadav candidates – 17 by the JD(U) in its share of 115 (14.78%), which was then with the NDA, and 16 by the BJP in its list of 110 (14.54%). The two thus hewed closer to the Yadav share in the population.

The BJP and JD(U) banked big on their core bases – upper caste-Baniyas and OBCs, and Luv-Kush (Kurmi-Koeri), respectively.

The BJP had 50 upper castes in its list of 110 (45%) and 17 OBC Vaishya candidates, while the JD(U) fielded 18 upper castes in its list of 115 (15.65%). The RJD had 12 upper caste nominees across 144 seats (8.33%).

The JD(U) fielded 12 Kurmi and 15 Kushwaha candidates, and the BJP 4 candidates each from the OBC groups.

The caste survey puts Bihar OBC numbers at 27.12%, and upper castes at 15.52%.

Among the EBCs, most of the parties preferred the Sahanis and Dhanuks, the major castes.

Of the JD(U)’s 26 EBC candidates, 7 were Dhanuk. The BJP fielded 5 EBCs and left 11 seats for alliance partner Mukesh Sahani’s Vikassheel Insaan Party, belonging to the Mallah community.

The RJD fielded 24 EBC nominees, 7 of them Nonias. A senior RJD leader told The Indian Express at the time: “We have applied serious thought to win over EBCs. While MY dominates our list but EBC representation is the takeaway from it.”

EBC votes are seen as floating votes because of their scattered population across the state and their lack of one overarching leader. With votes divided along caste lines in the state, EBC voters are often the deciders.

B

Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Oct 3, 2023: The Indian Express

Bihar’s population currently stands at 13.07 crore, out of which 36% (4.70 crore) are EBCs and 27% (3.5 crore) are OBCs, according to the caste survey data. What is the political import of these findings?

What about the forward castes?

The so-called “forward” castes or “General” category is only 15.5% of the population, the survey data, which were released by the state Development Commissioner Vivek Singh, show.

The data also shows that there are about 20% (2.6 crore) Scheduled Castes (SCs), and just 1.6% (22 lakh) Scheduled Tribes (STs). The table below (non-exhaustive) shows the percentage-wise breakup of some prominent sub-castes as per Bihar government’s data.

| Backward Classes | |

| Yadav | 14.26% |

| Khushwaha | 4.21% |

| Kurmi | 2.87% |

| Bania | 2.31% |

| Extremely Backward Classes | |

| Kevart | 0.2% |

| Kevat | 0.71% |

| Mallah | 2.6% |

| Teli | 2.81% |

| Nai | 1.59% |

| Dhanuk | 2.13% |

| Gangota | 0.4% |

| Chandravanshi (Kahar) | 1.64% |

| Nonia | 1.91% |

| Prajapati (Kumhar) | 1.40% |

| Badhai | 1.45% |

| Bind | 0.98% |

| Scheduled Castes | |

| Chamar/ Mochi/ Ravidas/ Charmkar | 5.25% |

| Dusadh/ Dhari/ Darahi | 5.31% |

| Mushahar | 3.08% |

| Pasi | 0.98% |

| Mehtar | 0.19% |

| Unreserved | |

| Brahmin | 3.65% |

| Rajput | 3.45% |

| Bhumihar | 2.87% |

| Kayastha | 0.60% |

| The percentages given here are with respect to the total population of Bihar. | |

Are the data unexpected?

Not really. The share of the OBC population, in both Bihar and elsewhere, has been widely believed to be much more 27%, which is the quantum of reservation that these castes get in government jobs and admissions to educational institutions.

The Mandal Commission, which presented its report in 1980, had put the share of the OBC population in the country as a whole at 52%.

The OBCs have long argued that even with reservations, the so-called forward castes have cornered a disproportionately large share of government jobs in comparison to their population.

What is the political import of this survey?

The caste survey is a key component of Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s bid political strategy, not only to stay relevant in state politics but to also play a leading role in the national opposition to the BJP.

The Chief Minister has woven his politics explicitly around the caste survey since 2022. While issues like the Uniform Civil Code and the inauguration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya in January next year are likely to play a major role in the BJP’s Lok Sabha campaign, Nitish is likely to use the survey data to give a rallying call for “social justice” and “development with justice”.

“Nitish is likely to use the caste survey as a Mandal 3.0 against the BJP’s Hindutva or ‘kamandal’ politics,” a senior JD(U) leader had told The Indian Express in August. The leader’s reference was to the implementation of the recommendations of the Mandal report in 1990 as Mandal 1.0, and Nitish’s emphasis on developmental politics in his first full term as CM in 2005 as Mandal 2.0.

The process of carrying out a caste survey in Bihar has found support from all political parties, including the Bihar BJP. The state unit of the BJP has repeatedly backed the proposals to conduct the caste survey. In 2021, it joined other state parties to meet Prime Minister Narendra Modi and to demand a nationwide caste survey.

Once the survey began, the state BJP unit rushed to claim its share of credit for the exercise — the party finds it hard to explain why its leadership at the Union government has been shying away from it.

How did the survey come about?

On June 1, 2022, after an all-party meeting, Nitish Kumar announced that “all nine parties (including the Bihar BJP unit) unanimously decided to go ahead with the caste census.” The next day, the state’s Council of Ministers approved the proposal to conduct the survey, using Bihar’s own resources and Rs 500 crore from its contingency fund for the exercise.

The survey’s first phase, which involved counting the total number of households in Bihar, began on January 7 and ended on January 21. The second and final phase kickstarted on April 15 to collect data on people from all castes, religions and economic backgrounds, among other aspects like the number of family members living in and outside the state.

The new phase was slated to wrap up on May 15 but it was stopped mid-way after the Patna High Court put a stay on it, saying the state government wasn’t competent to carry out the survey. Subsequently, the Bihar government approached the Supreme Court, seeking a stay on the order. However, the top court refused to do so, observing that the High Court had kept the matter for hearing on July 3.

“We will keep this pending. If the High Court does not take it up on (June) 3rd we will hear it,” the bench said.

A huge relief came for the state government on August 1, when the High Court ultimately said the survey was “perfectly valid”. The next day, the caste survey resumed. On August 25, Nitish said the survey had concluded. Now, the findings of the survey have been made public.