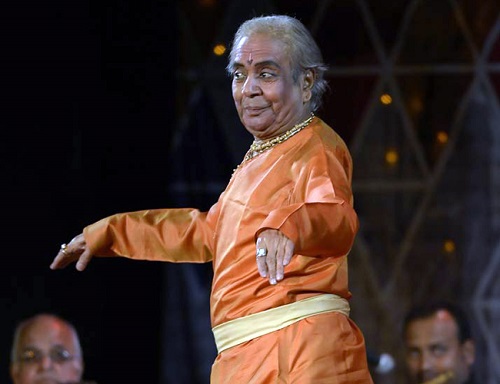

Birju Maharaj

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A profile

India Today, March 3, 2014

S. Kalidas

The Last Maharaj of Lucknow

The traffic snarl around the famed Safed Baradari-a white, twelve-door pavilion built by Nawab Wajid Ali Shah in the 1850s-tells you that laidback Lucknow has been jolted somewhat. It would seem the entire city has turned up to relive a forgotten history. Birju Maharaj, 76, has returned after a gap of some years to perform where his ancestors had danced at the courts of the nawabs of Awadh and laid the foundation of what is now known as the Lucknow Gharana of kathak.

He has come for the annual Mahindra Sanat Kada Festival organised by Madhavi Kukreja's NGO by the same name. With music, dance, storytelling, theatre, Awadhi food, textiles, qawwali, chikan embroidery and other crafts on display, it has become the must-attend event on the local festival calendar. "It took a Punjabi woman's drive to bring about a cultural renaissance in this hubris-ridden city," says historian Saleem Kidwai, who belongs to the old Lucknowi elite. "I am so happy to be back in the city of my birth," announces the veteran kathak master as he takes the stage. "I dance all over India and the world but dancing here is different. I was born here, just down the road at Gola Ganj. My father, my uncles and my grandfather and his brother, and two generations before them, all lived and danced here," he adds. Over the last hundred years, fate, fame and fortune took them away-to Raigarh, Rampur, Bombay (as it was called then) and Delhi, which became the capital of free India. "Now I really wish to return to Lucknow," says the Delhi-based Maharaj of kathak, upon whom the government bestowed the Padma Vibhushan, the second highest civilian honour, in 1986.

Over the next two hours, Birju and his troupe of dancers and musicians, led by his prime disciple Saswati Sen and son Jaikishan Maharaj, keep the audience riveted under a tented pandal despite the winter chill. Lucknow kathak is a compelling combination of bodily grace, complex rhythms, lyrical melody and narrative mime. What began as a storytelling (kathakaar) tradition where the narrator sang, spoke, mimed and danced to mythological tales in temple courtyards, developed into a highly sophisticated canonised form of court dance under the patronage of the nawabs of Awadh, especially the last prodigal Wajid Ali Shah whose deposement by the British led to the war of 1857.

This evening, apart from surprisingly agile footwork and pure dance sequences, Birju Maharaj sings and mimes to a thumri in the raga Gaur Mallar that his grand-uncle Bindadin Maharaj had composed. Time stands still as the ageing master transforms before your unbelieving eyes into a bashful maiden complaining of the pranks played by Krishna. His mastery over bhaav batana (art of telling an idea/tale through mime and song) is truly transporting. With large luminous eyes, facial expressions, animated hand gestures and minimal body movements, he casts a spell that makes you experience the narrative as if you were living it from the inside.

"Maharaj has a tremendous imagination that converts the whole world, even everyday things he sees around him, into an abstract language of gesture and rhythm," says leading critic Leela Venkataraman. Indeed, from the chirping of birds in nature to the editing of a film in an editing suite to the moving of files in a government office-nothing escapes the amazing art of Birju Maharaj. Old timers in Lucknow and Delhi still remember his uncle Shambhu Maharaj for this art with great nostalgia. Birju, too, touches his ear in respect, a gesture commonly used by subcontinental musicians and dancers when recalling a revered teacher or master, when he talks of Shambhu Maharaj's bhaav batana. "My father, Achchhan Maharaj, died when I was very young. After his death, I honed my skills under my uncles Lachchhu Maharaj, who lived in Mumbai, and Shambhu, who taught at Sumitra Charat Ram's Bharatiya Kala Kendra in Delhi," he says.

Achchhan Maharaj, originally named Jagannath Prasad, went to colonial Delhi in 1936 to teach at the Hindustani School of Music and Dance started by Jawaharlal Nehru's friend Nirmala Joshi. Among his first students from among the girls of the so-called 'respectable' Delhi families were Kapila Vatsyayan, Reba Vidyarthi and Sharan Rani Mathur. Before coming to Delhi, he had done long stints in the courts of Raja Chakradhar Singh in Raigarh and Nawab Raza Ali Khan in Rampur. A rotund man, he was nonetheless so nimble on his feet that the famous vocalist Ustad Faiyyaz Khan said of him: "Though built like an elephant, Achchan Maharaj is so graceful that it seems a fairy is dancing on a bed of sugar candy." Horrified by the pre-Partition riots in Delhi, he returned to Lucknow only to die suddenly in the summer of 1947, aged 64. By then, his nine-year-old son Brijmohan (Birju) had already started performing and took on the responsibility of looking after his widowed mother.

"After my father's death, I learnt from both my uncles though mostly by observing them practice and perform," says Birju. Baijnath Prasad, the middle brother better known as Lachchhu Maharaj, had made Mumbai his domain and taught many filmstars of yesteryear-from Meena Kumari, Nargis, Kumkum and Waheeda Rehman, down to Jaya Bachchan. He also choreographed dance sequences for several films including the Thaare Rahiyo song in Kamal Amrohi's Pakeezah. Shambhunath Prasad or Shambhu Maharaj, the youngest brother, lived and taught in Lucknow and Delhi. He was a great singer and famous for his mesmerising bhaav bataana and mellifluous thumris.

Their ancestral home, or what remains of it, is situated in a modest locality called Gola Ganj, less than a mile from Wajid Ali's Kaiserbagh. It used to be called Kalka-Bindadin ki deodhi (Kalka-Bindadin's abode). The roof of the main house has fallen but the arched mehrabs and walls made of thin Lucknowi lakhori bricks boast of a hoary past. Shambhu Maharaj's family still lives at the rear end of the house. "I want to restore this historic house and bring kathak back to Lucknow," says the Maharaj, hoping that the present political dispensation in Uttar Pradesh will help him achieve that goal. "This is where it all began," he reminisces, "where I grew up flying kites from Babban's shop around the corner. I recall playing Holi in the empty drums of Hamid bhai's laundry across the street (Hamid Rizwi's son now owns all of Lucknow's laundries, besides a few hotels and restaurants). The maulvi sahib of the nearby mosque was quite tolerant of our music and dance throughout the year, and we in turn would not put on our ghungroos or play loud music during Muharram. There was never a Hindu-Muslim riot in Lucknow in our time."

This family of Katthaks (caste) came from Handiya, a village in Allahabad district, and got patronage here even before Nawab Wajid Ali's time. Wajid Ali was Awadh's Nero. A poet, composer and dancer, he was so immersed in the pursuit of pleasure that he had little time to administer his kingdom. He had given this house, which became famous among musicians and dancers across India, to Birju's grandfather and grand-uncle Kalka Prasad and Bindadin Maharaj. The duo had become so famous for their art that not only were they invited by many other Indian princes to perform at their courts, but also every nautch girl or tawaif worth her salt from Kolkata to Mumbai, including the legendary Gauharjaan, came to Lucknow to be trained by them here. Bindadin was a prolific composer and left behind hundreds of musical compositions that are sung and danced all over India even today.

Birju remembers how, on Thursday evenings (jumme raat, the Sufi day of samaa) Shambhu Maharaj would sit under a guava tree in the courtyard with his close friends and perform informally for them. "It was not public performances, but intimate mehfils, where he was at his best," he says, pointing to the guava tree which has refused to die despite years of ruin all-round. Kathak, too, will survive like the guava tree, long after the tales of nawabs and colonial concubines are gone and the world has changed. In the meanwhile, if we restore Kalka-Bindadin's house, we'd only be doing our duty to history.

As a teacher

Navina Jafa, January 22, 2022: The Indian Express

Maharaj ji (as he was lovingly called) taught the seekers with generosity. He stands tall among classical dance gurus in creating Kathak as a constituency of an all-inclusive democratic world. Through Kathak Kendra, the National Institute of Kathak Dance, he nurtured and presented the form, making it a part of the eclectic and popular culture of the country.

His students and musicians are from different economic classes, gender, religions, regions and castes. “Once in the early 1980s, while living in the Kathak Kendra hostel, I was ill with malaria. My meagre scholarship did not cover the additional medicines and food expenses. Maharaj ji came to visit me and before leaving, he slipped a hundred rupee note,” recalls Shibli Mohammad, his student and now a famous guru and performer in Bangladesh.

Maharaj ji’s meditative knowledge of dance explored the universality of common images. “It was amazing to see him teach his Guyanese student, Phillip McClintock. It was the first production of ‘Katha Raghunath Ki’, an adaptation of Goswami Tulsidas’s Ramayana staged in 1977. Maharaj ji selected him to enact the role of Jatayu, the demi-god vulture. Phillip, who did not know the sacred text, was shown how to use his arms to enact the power of the wings. His arms, stomach, back muscles and his breath were in sync with the movement of his feet. Maharaj ji’s recreation of the persona of the vulture was one of rhythm and lucidity, communicating the clogged and frenetic power of the bird, with an innate spiritual character,” recalls Bipul Das, who came from Assam to learn with Maharaj ji in 1976. On stage, McClintock’s dark, naked torso was an engineered poetry of sinew and movement.

Maharaj ji’s philosophy of a well-balanced life combined sur (note), taal (beat), bhaav (emotion) and laya (rhythm). Mohammad remembers the time he arrived for his admission interview in Kathak Kendra, as a recipient of a scholarship from the Indian Council for Cultural Relations in 1982. He presented what he thought he had mastered, a unique composition called thaat, which is performed at the beginning of a performance, and is defined by sublimity and poise. Although he was selected, Maharaj ji chuckled and asked Mohammad, “Were you on a battlefield?”

Maharaj ji believed that the arts was an interconnected world of human creativity and transcended all mediums. Therefore, he encouraged us to observe dance in other art forms and not be limited to dance itself. “Observe when Pandit Bhimsen Joshi sings, the manner his body moves with the music, that too is dance,” he said.

Maharaj ji was a self-taught percussionist, musician, poet, and painter. In 2017, as part of a programme organised by Centre for New Perspectives, a Delhi think-tank, I invited him along with his disciple Saswati Sen to direct 24 street folk performers representing 10 art forms to assist in repositioning them on stage and giving them a sustainable future. He deliberated with puppeteers, acrobats, magicians and snake-charmers with such humour and ease. He developed a production called ‘Dilli Ka Bioscope’, which was presented at the World Bank India office, the Delhi Gymkhana Club and the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. His training may not have created top performers, but it certainly ensured that many acquired a skill to earn a livelihood.

Maharaj ji used Kathak as a language to communicate universality, often leading to extraordinary creative pieces that centred around images of everyday objects and situations. He taught us complex footwork inspired by south Indian rhythmic patterns and syllables. Seeing us struggling to imbibe the composition, Maharaj ji explained using a mundane image: “Imagine three small chickens walking in a line behind the mother hen. Then one deviates and comes out of the line. The mother turns around, opens her wings and brings the naughty chick back into the line.” Within minutes we reproduced the exact pattern keeping the entire imagery in mind. Many students use this technique even today.

Shaky Singh, a student of Maharaj ji, with Sen and a few others took care of their mentor throughout the COVID-19 lockdown. Singh says, “Maharaj ji had adapted himself to online teaching, though he maintained that it could not replace the classroom. For this very reason, he taught not more than two students at a time. Many of them were old students in different parts of the world who knew his style and way of communication.”

His farewell was as grand as the legend himself. His students, led by Sen, recited the mantras of dance syllables; the flowers on his body reverberated his joyful spirit. In my last interview with him (for The Hindu, in April last year on his compilation of poems called Brij Shyam Kahe), I asked him, ‘Who are you?’. He replied, “I am without form and am merely a vichaar dhara (a thought process) to create a better world.”