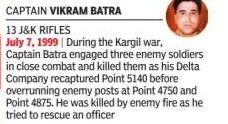

Captain Vikram Batra

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Martyrdom

Rachna Bisht Rawat, Sep 9, 2023: The Indian Express

It takes a one-and-half-hour flight out of Delhi and then as much time by road to drive from Kangra airport to Bandla Gaon in Palampur, Himachal Pradesh. The snow-covered Dhauladhar ranges appear and disappear at bends in the winding road and dazzle you with their magnificence. And the fragrant white roses that dot the airport and make the tourists gasp in pleasure follow you all the way to Vikram Batra Bhawan, where the late Captain Vikram Batra’s old parents stay in a bright-yellow-walled bungalow. There, they stop and bloom outside the room where an oil portrait of Capt Batra hangs on a wall. His father [GL Batra] sits before it, draped in a pashmina shawl, asking his wife [Kamal Kanta] to get you a hot cup of tea, or lay the table for lunch or just corroborate what he is saying from the confines of her bedroom where she is reading the local newspaper. One of the twins would actually hold the medal in his hand one day. The other wouldn’t, but he would be the one responsible for getting it home — this boy was the feistier of the twins. His name was Luv. The same Luv, who would become Capt Vikram Batra, the 24-year-old soldier who fought for his country on the rocky mountains of Kashmir, and died trying to save another soldier. When she was blessed with twins after the birth of two daughters, Kamal Kanta would wonder sometimes why she had been given two sons when she had asked for just one. “Now I know. One of them was meant for the country and one for us,” she would later say. All she has of Vikram are portraits and pictures and medals and memories that she is happy to share.

She remembers the day a colleague at the school where she used to teach had told her that she had spotted Vikram at the hospital. Panicking, she had rushed there to find him with a few cuts and bruises on his body, smiling broadly. He had jumped out of the moving school bus when the door had opened suddenly at a steep turn and a little girl had lost her balance and fallen off. When his upset mother had asked him why he had been so foolhardy, he had told her he was worried that the girl would come under another bus. Right from his childhood, Vikram was bold and fearless and always ready to help a person in need. Another time, he ran from pillar to post trying to get a gas cylinder for a new teacher in the school. The teacher had just moved to Palampur and asked for Vikram’s help when he had just not been able to manage one despite all efforts. Vikram promised him that he would get him a cylinder by evening and had kept his word, carting it all the way to the teacher’s house in an auto-rickshaw from the market. In addition to his gregarious nature — he had a vast circle of friends — his inclination to help any and everyone and his happy temperament, Vikram was brilliant at studies and a national-level table tennis player. He was judged the best NCC Air Wing cadet for North Zone. He had even received a call letter from the merchant navy and got all his uniforms stitched, but at the last moment decided not to join, telling his beleaguered father that his dream was to become an Army officer. He took admission in Chandigarh, prepared for the combined defence services exam and got through just as he had promised his parents. The Batras went for his passing-out parade. They were thrilled to see their handsome son in uniform and wondered just how high he would go. They didn’t know then that a few years later, the then Chief of Army Staff, General Ved Prakash Malik would sit in their house and tell them that if Vikram had not been martyred in , he would have been sitting in his office one day. It would make Mr Batra’s chest fill with pride in spite of the tears threatening to spill over.

Yeh dil mange more!

13 Jammu and Kashmir Rifles (JAK Rif) had completed its Kashmir tenure and the advance party had reached Shahjahanpur, its new location when it was recalled because war had broken out. After crossing the Zoji La Pass and halting at Ghumri for acclimatization, it was placed under 56 Brigade and asked to reach Dras to be the reserve of 56 Brigade for the capture of Tololing. 18 Grenadiers had tried to get Tololing in the initial days of the conflict but had suffered heavy casualties. Eventually, 2 Rajputana Rifles had got Tololing back. After the capture, the men of 13 JAK Rif walked for 12 hours from Dras to reach Tololing where Alpha Company took over Tololing and a portion of the Hump Complex from 18 Grenadiers. It was at the Hump Complex that commanding officer (CO) Lieutenant Colonel Yogesh Joshi sat in the cover of massive rocks and briefed the two young officers he had tasked with the capture of Pt 5140, the most formidable feature in the Dras sub-sector. They could see the peak right in front with enemy bunkers at the top but from that distance they could not make out the enemy strength. To Lt Vikram Batra of Delta Company and Lt Sanjeev Jamwal of Bravo Company, that didn’t matter. They were raring to go. Col Joshi had decided that these would be the two assaulting companies that would climb up under cover of darkness from different directions and dislodge the enemy. The two young officers were listening to him quietly as he spoke. Having briefed both, he asked them what the success signals of their companies would be once they had completed their tasks. Jamwal immediately replied that his success signal would be: “Oh! Yeah, yeah, yeah!” He said that when he was in the National Defence Academy, he belonged to the Hunter Squadron, and this used to be their slogan. Lt Col Joshi then turned to Vikram and asked him what his signal would be. Vikram thought for a while and then said it would be: “Yeh dil mange more!” Despite the seriousness of the task at hand, his CO could not suppress a smile and asked him why. Full of confidence and enthusiasm, Vikram replied that he would not want to stop after that one success and would be on the lookout for more bunkers to capture.

Capture of Point 5140

It was a pitch-dark night. Lt Col Yogesh Joshi was sitting at the base of the hump from where preparatory bombardment of Pt 5140 had commenced. He was trying to make out the movement of his troops he knew would be climbing up under cover of darkness. The Indian artillery had plastered the entire feature with high explosives. For a long time, it appeared as if the mountain was on fire and Joshi hoped that the enemy on top was dead. His hopes were, however, dashed very quickly. The Pakistanis had occupied reverse slope positions when the Indian artillery was pounding them and had now returned to fire at the Indian soldiers climbing up. From time to time, Joshi would see flashes on the dark mountain. From that he would know that the enemy was firing at his men and also just where the two teams had reached. The enemy had also started using artillery illumination at regular intervals, which lit up the entire area for about 40 seconds. This was done to spot the climbing Indian soldiers. Joshi hoped that his boys were following the standard drill, which was that everyone freezes and tries to blend into the surroundings when the area lights up like daylight. Movement would make them visible. Suddenly, his radio set came alive and he could make out the voice of a Pakistani soldier. He was challenging Batra, whose code name Sher Shah the enemy had intercepted. “Sher Shah, go back with your men, or else only your bodies will go down.” The radio set crackled and then he heard Batra reply, his voice pitched high in excitement: “Wait for an hour and then we’ll see who goes back alive.” At 3.30 am, the CO’s radio set crackled again. “Oh! Yeah, yeah, yeah!” It was Jamwal signalling that his part of the peak had been captured. Batra and his team were taking longer since they were climbing up the steeper incline. The next one hour was to be one of the longest for Lt Col Joshi. He could hear gunfire and see the flash of gunpowder, but had no idea what was happening at Pt 5140. Finally, at 4.35 am, in the cold of the darkness, his radio set beeped again and he heard the now-famous words: “Yeh dil mange more!” It was Batra. He and his men had captured the peak and unfurled the Tricolour there. What was most amazing was that in this attack, the Indian side did not suffer a single casualty. After coming down, Batra would call his parents on the satellite phone. For a moment, his father would stop breathing because he would just hear ‘captured’ and feel that he had been captured. But then the laughing soldier would clarify that he had actually captured an enemy post. He would then call his girlfriend Dimple in Chandigarh and tell her not to worry. He was fine and she should take care of herself. That was the last time he would speak to her. Vikram’s next assignment would be Pt 4875, from where he would not come back alive but he would leave Dimple with memories she was willing to spend a lifetime with. The battalion was de-inducted from Dras to Ghumri to rest and recoup. Less than a week later, they moved to Mushkoh. This was where greater glory was in store for Vikram.

The Last Victory

July 7, 1999

The wind was like a knife — cold and sharp — and Capt Vikram Batra, who had been promoted after his first assault in June, knew it could slice the skin right off his cheekbones. To an extent, it already had. That was why he and his 25 men from Delta Company, 13 JAK Rif., blended in so well with the barren landscape. Their grey, sunburnt faces with unkempt beards and tissue peeling off under the wind’s painful whipping merged perfectly with the massive boulders behind which they were taking cover. Pt 4875 was still 70 metres away and their task had been to reach that ridge, storm the enemy and occupy the post before daylight. Unfortunately, the evacuation of Capt Navin, who had a badly injured leg, had taken time and it was already first light. Through the night the men had been climbing the slope with machine gun fire coming almost incessantly from the top of the ridge. Intermittently, their faces would glow in the red light of the Bofors fire that was giving them cover from the base of the Mushkoh valley. The morning of July 7, there was a lot of pressure to proceed. Lt Col Joshi spoke to Batra at 5.30 am and asked him to reconnoitre the area with Subedar Raghunath Singh. Just before the point was a narrow ledge where the enemy soldiers were and it was almost impossible to go ahead. There was no way from the left or right either and, on the spur of the moment, Batra decided that even though it was daylight he and his boys would storm the post in a direct assault setting aside all concerns for personal safety, he assaulted the ledge catching the enemy unawares but they soon opened fire. Though injured, Vikram continued his charge, with supporting fire from the rest of the patrol and reached the mouth of the ledge, giving the Indian Army a foothold on the ledge. This was when he realized that one of his men had been shot. Even as he tried to keep his chin down with a shot whistling over his head, his eyes rested on the young soldier who had been hit and was lying in a pool of blood just a few feet away. Till a short while ago he had been crying out in pain. Now he was silent. His eyes met those of Sub Raghunath Singh, who was sitting behind a nearby boulder, maintaining an iron grip on his AK-47. “Aap aur main usko evacuate karenge,” Batra shouted above the din of the flying bullets. Raghunath Sahib’s experience told him that the chances of the boy being alive were slim and they shouldn’t be risking their own lives trying to get him from under enemy fire. But Batra was unwilling to leave his man. “Darte hain, Sahib?” he taunted the JCO. “Darta nahin hun, Sahib,” Raghunath replied and got up. Just as he was about to step into the open, Batra caught him by the collar: “You have a family and children to go back to, I’m not even married. Main sar ki taraf rahunga aur aap paanv uthayenge,” he said, pushing the JCO back and taking his place instead. The moment Batra bent to pick up the injured soldier’s head, a sniper shot him in the chest. The man who had survived so many bullets, killed men in hand-to-hand combat and cleared bunkers of Pakistani intruders, fearlessly putting his own life at stake so many times, was destined to die from this freak shot.

When he was in Sopore sometime earlier, Batra had had a miraculous escape when a militant’s bullet had grazed his shoulder and hit the man behind him killing him on the spot. He was surprised then. As he lay dying, destiny surprised him yet again. He had plans to follow, he had tasks to achieve, an enemy to vanquish. He was surprised that the bullet had found its mark despite all those unfulfilled duties. Batra gasped in disbelief and collapsed next to the young soldier he had wanted to give a dignified death to. The blood drained out of his body even as his stunned men watched in horror. Spurred by Batra’s extreme courage and sacrifice, a squad of 10 of his men (each carrying one AK-47 rifle, six magazines and two No 36 hand grenades) attacked through the ledge, found the Pakistanis making halwa and killed each of the enemy soldiers on top, with zero casualties of their own in that assault The fierceness of their attack frightened the Pakistani soldiers so much that many of them ran to the edge and jumped off the cliff, meeting a painful end in the craggy valley. Even in his death, Vikram Batra had kept the promise he had made to a friend casually over a cup of tea at Neugal Café in Palampur, on his last visit home. When his friend had cautioned him to be careful in the war, Batra had replied: “Either, I will hoist the tri-colour in victory or I’ll come back wrapped in it.”Excerpted with permission from The Brave: Param Vir Chakra Stories by Rachna Bisht Rawat (published by Penguin India)