Caste-based reservations, India (the results, statistics)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Dropout rate

The IITs: 2021

40% belong to SC/ST communities; 88% of IIT Guwahati dropouts, 76% of IIT Delhi from reserved categories.

Almost 63% of the undergraduate dropouts at the top seven Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) over the last five years are from the reserved categories, according to Education Ministry data given in response to a question in the Rajya Sabha. Almost 40% were from the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities. In some institutions, the SC/ST share was as high as 72%.

This indicates that those who drop out of these elite programmes disproportionately belong to the disadvantaged groups, given that only half the undergraduate intake in the IITs are from reserved categories, while about 23% are from the SC/ST communities. Dalit and Adivasi activists have long argued that students from those communities face a higher level of pressure and discrimination at these prestigious institutions.

However, Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan told the Rajya Sabha that the dropouts were “mainly on account of securing seat in other departments or institutions of students choice or on any other personal ground”.

Kerala MP’s query

He was responding to a question from Kerala MP V. Sivadasan regarding undergraduate dropouts at all centrally-funded technical institutions, the variance seen across social categories and the measures taken to address it. The Minister listed “fee reductions, institute scholarships, priority access to national level scholarships to aid students with poor financial backgrounds to pursue their education” among the steps taken to prevent dropouts.

An analysis of the seven IITs that stand in the top 10 of the National Institute Ranking framework shows that the disproportionality of dropouts is starker at some institutions. IIT Guwahati holds the worst record, with 88% of its 25 dropouts hailing from the reserved categories. In fact, almost three-fourths of all dropouts are from the SC/ST communities, although they make up less than a quarter of the students.

Of the 10 students who dropped out of IIT Delhi in 2018, all were from the reserved categories, a trend that holds true for every year except 2019. More than half of all the dropouts in IIT Delhi are from the SC/ST communities and 76% of its dropouts are from the reserved categories.

Top ranked IIT Madras has only had 10 dropouts over the last five years, but six of them have been SC/ST students, while another was from an Other Backward Class community. Overall, 70% of the institution’s dropouts were from the reserved categories

IIT Kharagpur has had the highest number of dropouts, with a whopping 79 students leaving the institution over the last five years. More than 60% are from the reserved categories.

IIT Bombay had the best record, with reserved category dropouts in proportion with their share of the total student intake, although SC/ST students fared worse.

However, Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan told the Rajya Sabha that the dropouts were “mainly on account of securing seat in other departments or institutions of students choice or on any other personal ground”.

Kerala MP’s query

He was responding to a question from Kerala MP V. Sivadasan regarding undergraduate dropouts at all centrally-funded technical institutions, the variance seen across social categories and the measures taken to address it. The Minister listed “fee reductions, institute scholarships, priority access to national level scholarships to aid students with poor financial backgrounds to pursue their education” among the steps taken to prevent dropouts.

An analysis of the seven IITs that stand in the top 10 of the National Institute Ranking framework shows that the disproportionality of dropouts is starker at some institutions. IIT Guwahati holds the worst record, with 88% of its 25 dropouts hailing from the reserved categories. In fact, almost three-fourths of all dropouts are from the SC/ST communities, although they make up less than a quarter of the students.

Of the 10 students who dropped out of IIT Delhi in 2018, all were from the reserved categories, a trend that holds true for every year except 2019. More than half of all the dropouts in IIT Delhi are from the SC/ST communities and 76% of its dropouts are from the reserved categories.

Top ranked IIT Madras has only had 10 dropouts over the last five years, but six of them have been SC/ST students, while another was from an Other Backward Class community. Overall, 70% of the institution’s dropouts were from the reserved categories

IIT Kharagpur has had the highest number of dropouts, with a whopping 79 students leaving the institution over the last five years. More than 60% are from the reserved categories.

IIT Bombay had the best record, with reserved category dropouts in proportion with their share of the total student intake, although SC/ST students fared worse.

Education

In JEE(A), OBC almost equal ‘open category:’ 2017

Quota Students From State Boards Rule Nos

The IITs, once the preserve of the educated elite in the metros, are witnessing a significant class shift.

As 1.7 lakh bright high school graduates take the IIT JEE (Advanced) on Sunday , data reveals that an almost identical number of open category and OBC candidates have qualified to take this final exam to enter the IITs.

Among aspirants from state boards, the ratio is, in fact, skewed in favour of back ward candidates as against the ones from the general quota. However, the qualifying score for backward candidates is 49 while for open category students it is 81.

In Maharashtra state board, while 4,394 from the ge neral category have made the cut, 7,460 from the OBC category and 4,619 SC candidates will appear for the JEE (Advanced) test. Similar is the case with Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh where a larger chunk of OBCs and the SCs have qualified for the IIT test through their school boards.) Even in case of the Guja rat, Telangana, Andhra, Kar nataka, Kerala and West Beng al state boards, a larger num ber of OBC students is compe ting for IIT seats vis-à-vis those from the open category .

“The make-up of candida tes taking the JEE this year has altered,“ said a JEE cha irman. Historically , CBSE schools have had the largest share of IIT seats, but the trend is changing. In 2012, 57% of candidates admitted were from CBSE, but by 2014, it had dropped to 42%.

This year, 64,000 JEE (Adv) candidates are from the non creamy layer of OBC and 69,000 from the general category . What that will translate to, said a JEE official, would be that several OBCs would qualify under the general category and not take a quota seat.

“Quite a few general category students of the 2.2 lakh who qualified after the JEE (Main) have dropped out and that may also be responsible in narrowing the (gap between) the number of OBC and general category students,“ said an IIT director.

As an individual board, CBSE dominated the merit list of the JEE (Main) exams for qualifying to the next level.Then came state boards like Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Maharashtra which also occupy a thick slice of the pie.

“Several state board schools and junior colleges are realising the importance of tests like JEE and NEET andopting for an integrated approach where students are trained for entrance tests,“ said Ruia College principal Suhas Pednekar.

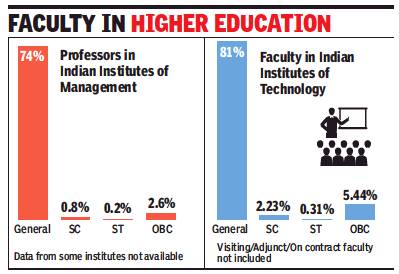

SC, ST, OBC professors in central universities/2018

Subodh Ghildiyal, Less than 5% of professors are from SCs, STs, March 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: Subodh Ghildiyal, Less than 5% of professors are from SCs, STs, March 6, 2019: The Times of India

No OBCs In Top Teaching Posts

Amid raging debate over the fallout of the Supreme Court judgment on the share of the backward classes in teaching positions in higher education, the government has provided official figures which show abysmal representation of SCs, STs and OBCs in faculties in central universities across the country.

The general categories (upper castes) comprise nearly 95% in posts of “professors” as against 3.54% SCs and 0.86% STs. There are no OBCs in the top teaching positions. The general categories represent 93% of posts of “associate professors” in stark contrast to 5% SCs and 1% STs, with no OBCs at all.

In the juniormost teaching position of “assistant professor”, general categories have a share of 66% as against 12% of SCs and 6% of STs. OBCs here count for nearly 15%. Across three categories, general communities have a share of 75%, SCs 10%, STs 4% and OBCs 10%.

Union ministry of HRD on February 6 provided to the Parliament’s “committee on welfare of OBCs” the caste-wise break up of faculties in higher education institutions. The panel is examining the implementation of reservation policy and if “creamy layer” for OBCs needs to be rationalised. Their representation marks a massive shortfall in comparison to the reservation available to SCs (15%), STs (7.5%) and OBCs (27%). Interestingly, the government recently carved out 10% reservation for the poor among the general communities (upper castes).

Blaming the “system of recruitment and implementation of quota policy” for the low share of backward classes in the faculties, Congress MP B K Hariprasad, who is a member of the OBC panel, said, “Even if SCs, STs and OBCs pass the examinations, there are many pretexts on which they are denied positions. That is the reason behind the deficit in their recruitment and population figures.”

Champions of social justice are concerned that the situation would get worse after the SC ruling that reservation in faculty positions should be calculated department-wise and not by taking the total seats in a university as the basis. Last week, the apex court rejected the government’s appeal against its judgment.

The new faculty quota policy has provoked a strong agitation for the restoration of the old system. Amid protests in Parliament, Union government in the recent budget session assured that it would bring an ordinance to wind the clock back.

2021

August 3, 2021: The Times of India

Over 55% of the sanctioned OBC posts in the 45 central universities and other technical and research organisations are lying vacant. This includes 89.8% of the OBC posts lying vacant in Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. The Union ministry of education (MoE) told the Lok Sabha that over 41% of the SC posts and 39% of the ST posts are also lying vacant in these institutions.

Replying to a written question on the total number of sanctioned and vacant posts in the reserved categories — SC, ST and OBC — in all central universities and research institutions, Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan in a response said being autonomous institutions, “the onus of filling up the vacant posts lies on Central universities.”

On the vacancies minister said: “Now, after implementation of ‘The Central Educational Institutions (Reservation in Teachers’ Cadre) Act, 2019’, the OBC reservation has been implemented at all levels. Further, in June 2019 UGC has prepared the Guidelines for Recruitment of Faculty in Universities, Colleges and Institutions Deemed to be Universities outlining the selection procedure and the time frame for recruitment which has been circulated to all Universities to adhere to the guidelines. The UGC on July 31, 2019, August 7, 2019, September 5, 2019 and October 22, 2019 has again requested the universities to ensure that vacant positions in university as well as colleges affiliated to University are filled at the earliest.”

As per the data provided by the ministry, as on April 1, 2021 the OBC vacancies are highest in central universities, Indira Gandhi National Open University, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISERs) and Indian Institute of Science (IISc) which is well above 50%.

'Merit, the dilution of'

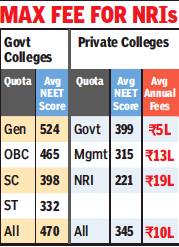

2017: Management/ NRI cut-offs way below OBC,SC,ST

Rema Nagarajan, Money, not quota, dilutes merit in med admissions, June 11, 2018: The Times of India

“Government seats’” cut-offs at private medical colleges were well below OBC cut-offs at government medical colleges and only marginally better than SC cut-offs at government medical colleges

From: Rema Nagarajan, Money, not quota, dilutes merit in med admissions, June 11, 2018: The Times of India

Higher The Fees, Lower The Avg NEET Score

It is not caste-based reservation but money that compromises merit in medical admissions. This is obvious from the difference of about 140 marks, or close to 20 percentage points, between the average NEET scores of admissions to over 39,000 government-controlled seats and those to the over 17,000 management and NRI quota seats in private colleges where fees determine admission.

TOI analysed details of nearly 57,000 students admitted to 409 colleges last year. The average NEET score of students in government-controlled seats was 448 out of 720, while the quotas under private control averaged just 306.

Incidentally, the average score of students admitted under the SC quota in government colleges was 398 and the overall average for SC students in all colleges was 367, both much higher than the overall average for privately controlled seats.

The conclusion that it is high fees that are driving this dilution of merit in private college admissions comes from looking at how fees and NEET scores are correlated (see graphic). The higher the range of fees, the lower the average NEET score.

As a result, the NRI quota, which typically has the highest fees, has the lowest NEET scores, a mere 221 on average.

Avg score in govt med colleges is 487

As a result, the NRI quota, which typically has the highest fees, has the lowest NEET scores, a mere 221 on average. The correlation between fees and NEET scores can be seen even in government colleges, some of which have started charging fees beyond the means of even middle-class families. The average score of students in government colleges where the annual fee is less than Rs 50,000, was 487, whereas for those with fees of a lakh or more, it was 372.5.

Assam vis-à-vis UP: how merit is being compromised by money

2017 figures

From: Rema Nagarajan, Med seats: Why pure merit works in Assam, not in UP, June 11, 2018: The Times of India

If medical admissions were entirely merit based what would be the cut-off percentile required to fill all seats? Without the entire list of NEET qualified students in the country, gauging this cut-off percentile is an exercise in approximation. However, the list of students who qualified from Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Assam, Kerala and Telangana are available in the public domain. An analysis of these shows that for all categories other than ST, even an 88th percentile cut-off (equivalent to a score of 340) would have ensured enough and more students qualified to fill seats available. For the ST category, this would be true at about the 75th percentile or above a score of 234.

The cases of Assam and UP are particularly illuminating to show how merit is being compromised severely by money in medical admissions. Assam has no private colleges, while UP has no government quota in its 22 private colleges with 2800 seats.

An analysis of NEET scores shows that in Assam, only 49 of the 603 students admitted were below the cut-offs that would have been needed (from 93rd percentile for unreserved to 74th for ST) to fill all the seats available if merit alone mattered and all students who qualified were willing to join.

In contrast, in UP, over 2,900 of the 4,908 students admitted were below the cut-offs calculated on the basis of merit (from 97th for unreserved and OBC to 75th for ST). About 95% of these students were in the private colleges in UP.

This happens because many high-scoring students from the different categories cannot afford the exorbitant fees charged by private medical colleges and are forced to drop out despite merit. This allowed rich students with scores as low as 17-18% at the 50th and 40th percentile cutoffs to grab the seats.

Instead of fixing the cut-off percentile based on the number of seats available and the marks scored by students in each year, the health ministry and the Medical Council of India fixed the cut-off in advance at 50th and 40th percentile. To make matters worse, with no stipulation on minimum marks in each subject, students with single digit marks in chemistry and physics, and a few with even zero and negative marks in these subjects have qualified and got admission. Despite this being brought to the notice of the health ministry and the MCI, the system remains unchanged.

In 2018, the eligibility scores fell even further to 119 (16.5%) and 96 (13.3%) for the unreserved and reserved categories respectively. “At this rate, they might as well remove the cutoff and say that anyone writing NEET will be eligible. Seats are still being sold thanks to such low cut-offs,” remarked Jawahar Shanmugham, petitioner in a case against the high fees in deemed universities.

Even with the government helping colleges fill the highpriced seats by keeping cut-offs as low as possible, many private colleges in Karnataka, Punjab, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra were in the news in 2017 for being unable to fill NRI seats, and in some cases even management quota seats, which forced them to slash fees. The seats remained vacant not because there weren’t meritorious students, but because there weren’t enough of them willing to pay such high fees.

Unsurprisingly, the biggest beneficiaries of the management and NRI seats are students from the unreserved category, accounting for over 60% of these seats (10,373 out of 17,243). OBCs account for almost 29% and SC and ST together amount to just 3%. The average score of unreserved students getting private seats (361.5) is less than the average score of SC category students in government colleges (367).

Performance of various reserved categories

EWS vis-à-vis OBC: 2024

Subodh Ghildiyal, June 22, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : The upper castes availing the economic backwardness quota have trailed the backward classes in the Mains examinations of the Civil Services competition for the last two years. But the dynamic of competitiveness between the two reserved categories is complex, as the forwards have prevailed in the ultimate test by virtue of greater score in the ‘interview’ part of the competition.

In the recent results for CS-2024, the cut-off for the Economically Weaker Sections category in the Civil Services (Main) exams was 696 marks as compared to 702 for the OBCs. But in the Final results after the interview, the EWS had a cut-off merit of 917 marks as against 910 for the OBCs. Under the EWS category, the non-SC/ST/OBC get 10% reservation on the basis of the poverty criteria.

The cut-off marks are the minimum qualifying score for a social bloc availing the reservations, and they vary across the categories of SC, ST, OBC, and EWS. In the Mains part of the CS-2023, the OBCs scored a cut-off of 712 as compared to 706 for the EWS. But in the Final, the OBCs trailed with a cut-off of 919 to the EWS which had 923 as the minimum marks.

The Mains-Interview contrast is seen as surprising. Shashank Ratnoo, a lawyer who specialises in reservation laws and issues, said, “There is no starkly noticeable reason for OBCs to have more marks in the Mains than EWS, yet lose out in the final cut off on account of EWS scoring better interview marks. It possibly shows that the EWS group has no or lesser social disadvantages that hurt competitiveness.”

Interestingly, the contrast in the merit for OBCs and EWS in the Civil Services Examinations has been a see-saw. In the wake of the fresh EWS quotas introduced in 2019, the OBCs dominated the Mains and the Final both in 2019 and 2020. While it was surprising that EWS, which has groups with lower social handicaps, trailed behind the OBCs, it was viewed as result of the fact that a new quota regime had just come into effect and the facts about its procedures and criteria had not percolated down to the wider eligible umbrella. Later, the EWS overhauled the gap with OBCs and came to score higher in the examinations.

According to Ratnoo, what is surprising is that EWS has notched a quicker rise in merit than possibly any social sub-group has done after coming under the reservation system. “It is interesting that the Centre (DoPT) recently ordered an inquiry into the income certificates of some EWS candidates who were selected in the civil services after the Final exams. Such closer scrutiny may help understand the issue better.”

Success stories

Andhra Pradesh/ Telangana

2024

In 2007, after debate and deliberation, the then Y S Rajasekhar Reddy-led govt of undivided Andhra Pradesh declared a 4% quota for 14 eco nomically backward sections of Muslim community in educational institutions and jobs.

Depending on which side one is in, the decision remains a hot-button topic.

A decade after the reservation tweak , the K Chandrasekhar Rao-led BRS govt in Telangana proposed to raise the quota to 12%. The Centre refused.

It is estimated that over 20 lakh Muslim students have benefited from the BC-E quota in the state to date, earning degrees in engineering, med icine, pharmacy, and business administration, among other fields.

Success stories resonate across AP and Telangana. Mohammed Shabbir Ali’s book, The Struggle, narrates dozens of accounts of Muslim girls and boys who embraced transformative change. Some who would probably have ended up as dhobis and tea stall “chhotus” now don doctor’s scrubs or a lawyer’s coat.

“Apart from bringing education to every home, reservation has served a larger purpose — reducing instances of unemployed youth being drawn into crime and girls getting married before even completing school,” says Shabbir Ali, who witnessed the reservation debate through the 1990s.

“Yes, they are hesitant to speak up today as they are scared of this window of hope being shut on their faces. I pray that those opposing reservations understand that this is not based on religion but to rectify the denial of opportunities. Withdrawing it will send lakhs of young people back into their dark past,” he added.

QUOTA ARITHMETIC in Telangana

➤ Muslims in Telangana account for around 10% of the state’s population of 6 crore

➤The 4% quota for 14 backward sections of the Muslim community in educational institutions and govt jobs was rolled out in 2007

➤ Muslim groups excluded from the quota are Syed, Saiyed, Sayyad, Mushaik, Mughal, Moghal, Pathan, Irani, Arab, Bohra, Shia Imami Ismaili, Khoja, Kutchi Memon, Jamayat and Navayat

➤ It is estimated that to date, over 20 lakh Muslim students have benefitted from this quota, earning degrees in engineering, medicine, pharmacology and business administration, among others

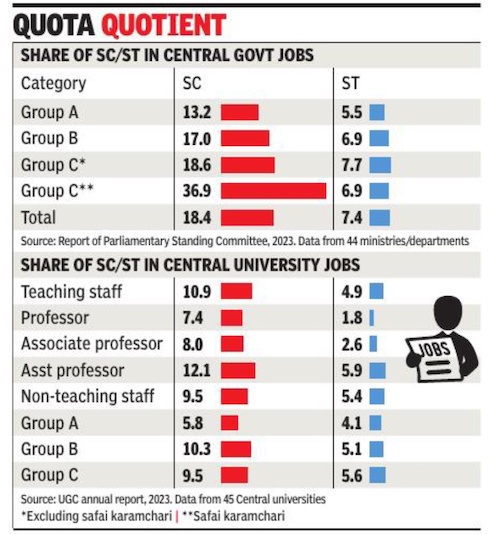

Unfilled posts

Rema Nagarajan, August 4, 2024: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, August 4, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi : While it is true that some sub-castes within scheduled castes and some tribes within scheduled tribes miss out on the benefits of reservation, a significant part of SC/ST quotas in govt jobs goes unfilled every year, raising the question of whether the ‘dominant’ subcastes and tribes are really keeping the more deprived ones out. Data also shows that the proportion of unfilled posts increases as we move up the chain towards more senior posts.

According to a 2023 report of the parliamentary committee on welfare of scheduled castes (SCs) and scheduled tribes (STs), the only category of jobs in ministries and departments of the central govt where SCs and STs have a share larger than their quota of 15% and 7.5% respectively are the Group C jobs excluding safai karamcharis and an even larger share among safai karamcharis or sanitation workers.

More than one third (37%) of the safai karamcharis employed in central govt ministries are from scheduled castes and 7.4% are tribals. In comparison, in Group A jobs just 13% are SCs and 5.5% are STs. Due to the high representation of S Cs and S Ts in lower categories of jobs, it looks like they more than fill their quota overall — 18.4% SCs and 7.4% STs in posts and services under the central govt.

According to the Parliamentary report, in spite of special drives, relaxation in qualifying criteria and prepromotional training, ministries or departments were unable to fill the thousands of backlog reserved vacancies. Thus, even with some ‘dominant’ scheduled castes or tribes taking advantage of the quotas, they remain unfilled year after year.

Data available on 45 central universities also shows a similar pattern. SCs constituted under 11% of teaching posts and S Ts less than 5%. In non-teaching posts, SCs had a share of under 10% and STs just a bit over 5%. Once again, the shares are lowest in the senior most positions.

“This fact is obfuscated by only talking of the overall representation of Dalits and tribals in govt jobs. There are thousands of unfilled posts in govt because the quotas are not being filled. Clearly, despite having a small section of relatively better off SCs, the govt is unable to fill the quota. It is estimated that barely 1.9% of S Cs earn above Rs 50,000. Most of these would be in govt service as historically SCs have no assets, neither land nor businesses,” pointed out M S Nethrapal, an Indian Revenue Service officer who researches issues of Bahujan representation in jobs and education. He added that there was not enough data on the various sub-categories within SC, as data is only collected at a broad level for all SCs as a single category.

The lack of sub-classification leading to the more deprived among SCs or STs missing out would hold true only if the quota was being filled. If the quota was not being filled, then nobody could be said to be missing out because someone else was getting through the quota. However, unlike in jobs/posts, the quotas usually get filled when it comes to seats in educational institutions run by govt, like medical colleges, engineering colleges and universities.

Where quotas are being filled, many Dalit activists support sub-categorisation so that castes within the SC category that face greater marginalisation could take advantage of the quota and find representation. “Such sub-categorisation, however, has to be based on the extent of discrimination or marginalisation faced by a caste within the SC category. It cannot be based on an economic criteria as in the case of OBCs,” said Nethrapal.

See also

Caste-based reservations, India (legal position)

Caste-based reservations, India (history)

Caste-based reservations, India (the results, statistics)

The Scheduled Castes: statistics

Scheduled Castes of Kerala (list)

Scheduled Castes in Tamil Nadu