Central India, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Central India

Physical aspects

An Agency or collection of Native States, under the political supervision of the Agent to the Governor-General in Central India, lying between 21° 22' and 26° 52' N. and 74° o' and 83° o" E. The head-quarters of the Agent to the Governor-General are at Indore. The Agency may be roughly said to asDect^^ consist of two large detached tracts of country, sepa-

rated by the wide and winding valley of the Betwa river, which, starting from Jhansi, spread out east and west into the Peninsula ; northwards its territories stretch to within 30 miles of Agra, and southwards to the Satpura Hills and the Narbada valley. The country has a general declination to the north, the land falling from an elevation of 2,000 feet above the sea along the Vindhyan range to about 500 feet along its northern boundary.

Central India is bounded on the north-east by the United Provinces of Agra and Gudh. On the east, and along the whole length of its southern border, lie the Central Provinces ; the south-western boundary is formed by Khandesh, the Rewa Kantha Agency, and the Panch Mahals of Bombay ; while various States of the Rajputana Agency enclose it on the west and north. The total area of this tract is 78,772 square miles, and the population (1901) 8,628,781 ; but, excluding areas situated in it which belong to States in Rajputana, and including outl)ing portions of Central India States, the area is 77,395 square miles and the population (1901) 8,510,317.

The name Central India, now restricted officially to the territories under the immediate political control of the Agent to the Governor- General in Central India, is a translation of the old Hindu geographical term Madhya Desa or the Middle Region, which was, however, used to designate a far larger and very different tract of country. The term Central India was officially applied at first to Malwa alone ; but in 1854, when the Bundelkhand and Baghelkhand districts were added to Malwa to form the present Central India Agency, it was extended to the whole tract.

There is a marked diversity in the physical aspects, climate, scenery, people, and dialects in different parts of the Agency, which falls into three natural divisions. These may be conveniently designated the plateau, the low-lying, and the hilly tracts. The plateau takes in most of Malwa, the wide table-land with a mean elevation of about 1,600 feet above the sea, an area of 34,637 square miles, and a population of 102 persons per square mile, which forms the major portion of the western section of the Agency. Malwa, taking the term in its widest application, includes all the country lying between the great Vindhyan barrier, which forms the northern bank of the Narbada valley, and a point just south of Gwalior ; its eastern limit is marked by the ridge which runs from south to north starting near Bhllsa, while its western limit marches with the Rajputana border.

The inhabitants of this tract are hard-working agriculturists, speaking for the most part dialects of Rajasthani. The low-lying division embraces the country round Gwalior, and to the north and north-east of it, extending thence across into Bundelkhand, of which it includes the greater part, till it meets the Kaimur Hills in Baghelkhand. The area of this tract is about 18,370 square miles, and the population 172 persons per square mile, its mean elevation being about 700 feet above the sea. The inhabitants are agriculturists, but of a more sturdy physical type, thick- set and of lower average stature than the Malwa peasantry. They speak chiefly dialects of Western Hindi. The hilly tracts lie principally along the Vindhya and Satpura ranges and their numerous branches. This division has an area of about 25,765 square miles, and a popula- tion of only 74 persons per square mile. The inhabitants are chiefly Bhils, Gonds, Korkus, and other tribes of non-Aryan or mixed descent, who practise but little agriculture and speak for the most part a bastard dialect compounded of Gujarat!, Marath!, MalwT, and Hindi.

Strictly speaking, there is but one range of mountains in Central India. In the south-western portion of the Agency this range is divided by the Narbada river into two parallel lines, the northern line being known as the Vindhyas and the southern as the Satpuras. The branch of the Vindhyas which strikes across Bundelkhand is termed the Panna range, while the arm which runs in a boldly defined scarp north of the Son river is called the Kaimur range. The small chain which links up the Vindhya and Satpura systems near Amar- kantak is called the Maikala. Other branches of less importance have local names.

This hill system, of which isolated peaks rise to over 3,000 feet above sea-level, has a marked effect on the climate of Central India, both from the high table-land which it forms on the west, and from the direction it gives to the prevailing wind at different seasons. At the same time it forms the watershed of the Agency. In the tract of country which lies north of the Vindhyas all streams of importance rise in this range and, except the Son, flow northwards, the Betvva, Cham- BAL, Kali Sind, Mahi, Parbati, Sind, and Sipra on the west, and the Dhasan, Ken, and Tons on the east, all following a general northerly course till they ultimately join the water-system of the Gangetic Doab.

There are no large rivers south of the Vindhyas except the Narbada, which, rising in the Maikala range, flows in a south-westerly direction till it falls into the sea below Broach. None of the Central Indian rivers is, properly speaking, navigable, though sections of the Narbada can be traversed for a few months of the year. No lakes deserve special mention except those at Bhopal, though large tanks are numerous, especially in the eastern section.

k\\ infinite variety of scene is presented. The highlands of the great Malwa plateau are formed of vast rolling plains, bearing, scattered over their surface, the curious fiat-topped hills which are so marked a charac- teristic of the Deccan trap country— hills which appear to have been all planed off to the same level by some giant hand. Big trees are scarce in this region, except in hollows and surrounding villages of old founda- tion ; but the fertile black cotton soil with which the plateau is covered bears magnificent crops, and the tract is highly cultivated. Where no grain has been planted, the land is covered with heavy fields of grass, affording excellent grazing to the large herds of cattle which roam over them. During the rains, the country presents an appearance of un- wonted luxuriance.

Each hill, clothed in a bright green mantle, rises from plains covered with waving fields of grain and grass, and traversed by numerous streams with channels filled from bank to bank. This luxuriance, however, is but short-lived, and, within little more than a month after the conclusion of the rains, gives place to the mono- tonous straw colour which is so characteristic of this region during the greater part of the year. Before the spring crops are gathered in, how- ever, this yellow ground forms an admirable frame to set off broad stretches of gram and wheat, and the brilliant fields of poppy which form a carpet of many colours round the villages nestling in the deep shade of great mango and tamarind trees.

In the eastern 'districts the aspect is entirely different. The undu- lating plateau gives place to a level and often stone-strewn plain, dotted here and there with masses of irregularly heaped boulders and low serrated ridges of gneiss banded with quartz, the soil, except in the hollows at the foot of the ridges, being of very moderate fertility, and generally of a red colour. Big trees are perhaps more common, and tanks numerous. Many of these tanks are of considerable antiquity, and are held up by fine massive dams. Though some are now used for irrigation, examination shows that they were not originally made for that purpose, but merely as adjuncts to temples and palaces or the favourite country seat of some chief, the low quartz hills lending them- selves to the construction of such works.

In the hilly tracts the scene again changes. On all sides lie a mass of tangled jungles, a medley of mountain and ravine, of tall forest trees and thick undergrowth, traversed by steep rock-strewn watercourses which are filled in the rains by roaring torrents. Here and there small collections of poor grass-thatched huts, surrounded by little patches of cultivation, mark the habitation of the BhTl, Gond, or Korku. Along the Son valley and the bold scarp of the Vindhyas, over which the Tons falls into the plains below in a series of magnificent cataracts, the scenery at the close of the rains is of extraordinary beauty.

Each tract has its history recorded in ruin-covered sites of once popu- lous cities, in crumbling palaces and tombs, decaying shrines, and mutilated statues of the gods.

1 Geologically, Central India belongs entirely to the Peninsular area of India. It is still to a large extent unsurveyed, yet such parts as have been more or less completely studied enable a general idea of its geological conformation to be given.

The most remarkable physical feature of this vast area, and one inti- mately connected with its geological peculiarities, is the almost recti- linear escarpment known as the Vindhyan range. From Rohtasgarh on the east, where the Son bends round the termination of the range, up to Ginnurgarh hill, in Bhopal territory, on the west, a distance of about 430 miles, the escarpment consists of massive sandstones belonging to the geological series which, owing to its preponderance in this range, has been called the Vindhyan series. At Ginnurgarh hill, however, the sandstone scarps take a sudden bend to the north-west, and trend entirely away from the \"indhyan range proper, though as a geo- graphical feature the range continues for almost 200 miles beyond Ginnurgarh. It no longer consists, however, of Vindhyan strata in the geological sense, being formed mostly of compact black basalts, the accumulated lava-flows of the ancient volcanic formation known as Deccan trap. It has been well estabUshed, by a geological study of this region, that the Vindhyan series is immensely older than the Deccan trap, and that the surface of the Vindhyar. rocks, afterwards overwhelmed by these great sheets of molten lava, had already been shaped by denudation into hills and dales practically identical with those which we see at the present day.

In the roughly triangular space included between the Vindhyan and Aravalli ranges and the Jumna river, which comprises the greater portion of the Central India Agency, rocks of the Vindhyan series prevail. The greater part of this area is in the shape of a table-land, formed mostly of Vindhyan strata, covered in places by remnants of the Deccan basalts, especially in the western part of Malwa, where there are great continuous spreads of trap. The Vindhyans do not, however, subsist over the whole of the triangular area thus circumscribed, owing to their partial removal by denudation. The floor of an older stratum, upon which they were originally deposited, has been laid bare over a great gulf-like ex- panse occupied by gneissose rocks, known as the Bundelkhand gneiss.

South of the Vindhyas, besides a strip of land, mainly alluvial, between the Vindhyan scarp and the Narbada, the Agency includes at its eastern and western extremities two large areas that extend a considerable ^ By Mr. E. Viedenburg of the Geologic.il Survey of India. distance southwards. The western area, bordering on Khandesh, includes a portion of the Satpura range mainly formed of Deccan trap. The eastern area comprises all the southern portion of Rewah, and includes an extremely varied rock series, the most extensive outcrop in it belonging to the Gondwana coal-bearing series.

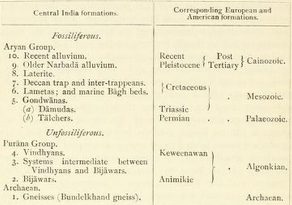

The geology of Central India is thus more complex than that of any other area of similar extent in the Peninsula : scarcely one of the Penin- sula groups is unrepresented, and it contains the type areas of several among them. The rock series met with may thus be tabulated : —

Among these, the first to arrest attention by reason of its preponder- ance is the Vindhyan series, covering a surface not greatly inferior to that of England. Of the eastern portion of their outcrop, occupying a considerable part of Bundelkhand and Baghelkhand, an excellent description will be found in Mr. Mallett's ' Vindhyan Series ' {Memoirs, Geological Survey of Itidia, vol. vii, part i). The Vindhyans consist of alternating bands of hard sandstones and comparatively soft flags and shales, which, owing to the marked differences that they exhibit in their degree of resistance to denudation^ give rise to the regular escarp- ments, capped by sandstones with an underscarp of softer rocks, which constitute the most noticeable physical feature of this region.

Three of the massive sandstones stand out so conspicuously that they are distinguished by special names. The lowest of these, which forms the outer ranges to both north and south, is called the Kaimur sand- stone, being chiefly met with in the range of that name. The next, forming the second or middle scarp, is called the Rewah sandstone after the State in which it is finely exhibited. The third scarp contains the newest rock of the whole group, called the Bandair (Bhander) sand- stone from the small range which it caps, to the south of Nagod.

Along the Vindhyan range proper, these three great scarps are not so clearly marked as elsewhere, but in the northern branch they stand out perfectly distinct. The northernmost range constituting the first or outer scarp is capped by Kaimur sandstone and exhibits very bold scarps, often almost vertical and quite inaccessible, deeply cut into by the river valleys. Numerous detached masses or outliers stand in front of the main line of escarpment, often crowned by those formerly impreg- nable fortresses which have played so important a part in the history of India, such as Kalinjar, Bandhogarh, and Ajaigarh. Along a portion of this scarp and in all the deep valleys that penetrate it, the Kaimur sandstone rests upon the flaggy limestones, underlaid by shales and thin bands of sandstone, which constitute the lower Vindhyans ; in most of the outliers, the Kaimur sandstone rests directly upon the Bundelkhand gneiss.

In the Son valley the sandstones contain a remarkable group of highly siliceous rocks known as porcellanites, a name which accurately describes their appearance. They are indurated volcanic ashes of a strongly acid type, containing a high percentage of silica. When the fragments of volcanic dust become sufficiently large to be distinguished without a magnifying power, the appearance of the rock changes to that of the variety designated as trappoid. These beds indicate an ancient period of intense volcanic activity. The beds below the porcellanites, the basal beds of the Vindhyans, consist of a variable thickness of shale, limestone, and conglomerate, the last being the oldest rock of the entire Vindhyan series. A very constant, though not universally present, division occurs in the Kaimur at the base of the massive sandstone, and is called the Kaimur conglomerate.

At the eastern extremity of the Rewah scarp, the entire thickness of the lower Rewah formation consists of a continuous series of shales, but in some parts of Bundelkhand this is divided into two portions by an intermediate sandstone. The shales below this sandstone are called the Panna shales, after the town of that name, and those above it Jhlrl shales, after a town in Ciwalior territory. A bed of great economic importance, the diamond-bearing conglomerate, is intercalated in the midst of the Panna shales. It is found only in some small detached outcrops near Panna and east of that place, and the richest of the cele- brated mines are those worked in this diamond-bearing bed. The diamonds occur as scattered pebbles among the other constituents of the conglomerate.

Tiie lower Bandairs of Bundelkhand and Baghelkhund closely resem- ble the lower Vindhyans ; like them, they are principally a shaly series with an important limestone group and some subsidiary sandstone. The limestone band is of considerable economic importance, yielding excellent lime. It is to a great extent concealed by alluvium, but comes into view in a series of low mounds, one of the best known being situated near Nagod, whence it has been called Nagod limestone.

On entering Central India at Bhopal, the Vindhyans are shifted so as to run to the north of the great faults, and the whole series again comes into view, presenting all the main divisions met with in Bundelkhand and Baghelkhand. Little alteration has taken place in the series, in spite of the distance from the eastern outcrops, except that the Panna shales are replaced by flaggy sandstones. The lower Bandairs and lower Vindhyans have changed in constitution, the calcareous and shaly element being replaced by an arenaceous development, giving the entire Vindhyan series a greater uniformity than it presents farther east. The scarps which form the northern part of the syncline in Bundelkhand curve round the great bay of Bundelkhand gneiss and continue up to the town of Gwalior, after which they sink into the Gangetic alluvium. The main divisions are represented here even more uniformly than in Bhopal. An additional limestone band is, however, intercalated among the Sirbu shales, known as the Chambal limestone. The lower Vindhyans are absent, the Kaimur conglomerate resting immediately on the Bundelkhand gneiss. In the neighbourhood of Nimach the Kaimur, Rewah, and Bandair groups are all represented.

No fossils have ever been found in the Vindhyans, so that their age still remains doubtful. It seems probable that the range, or at least the greater part of it, is older than the Cambrian series in England, which would account for its unfossiliferous nature.

Next in importance to the Vindhyan series, by reason of the vast area which it occupies, is the Bundelkhand gneiss, forming, as already mentioned, a great semicircular bay surrounded by cliffs of the over- lying Vindhyans. The Bundelkhand gneiss is regarded as the oldest rock in India. It consistsprincipally of coarse-grained gneissose granite, and is very uniform in composition. The gneiss is cut through by great reefs of quartz striking nearly always in a north-easterly direction, which form long ranges of steep hills of no great height with serrated summits, and cause a marked difference in the scenery of the countrj-. This formation gives special facility for the construction of tanks. Innumer- able narrow dikes of a much later basic volcanic rock cut through the Bundelkhand gneiss. Towards the Jumna the gneiss vanishes below the Gangetic alluvium.

As a rule, the sandstone cliffs which surround the gneiss rest directly on that rock. In places, however, an older series intervenes, named after the Bijawar State in which its type area is found. The same series is met with near Gwalior town, forming a range of hills that strikes approximately east and west. The identity of these rocks with the Bijavvars is now determined ; they were, however, long regarded as of a different type and were known as the GwaUor series. Other outcrops of these series are met with in the Narbada valley and south of the Son, These rocks have been subjected to far more pressure and folding than the Vindhyans, and their shales have been converted into slates and their sandstones into quartzites, while the bottom bed is invariably a conglomerate full of pebbles of white quartz.

The most characteristic rocks of the Bijawars are the layers of regularly banded jaspers which are frequently intercalated among the limestones. They usually contain a large proportion of hematite, giving them a fine red colour, which makes them highly ornamental and in great demand for inlaid decoration, such as that worked at Agra. The proportion of hematite is often high enough to make it a valuable iron ore, and the sites of old iron workings may be met with everywhere on the Bijawar outcrops. In Bijawar itself the ore has become concentrated in a highly ferruginous lateritic formation, which must have accumulated in the long period that intervened between the deposition of the Bija- wars and Vindhyans. (See 'Geology of Gwalior and Vicinity,' Records, Geological Survey of India, vol. iii, pp. 33-42 ; vol. xxx, pp. 16-41.)

The series underlying the Vindhyans to the south of the Son river are very complex. (See ' Geology of the Son Valley,' Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vol. xxxi, part i.)

The Archaean rocks met with in the Narbada valley in Nemawar, at Bagh and Ah Rajpur, conform in character to the Bundelkhand gneiss. The forces that so violently disturbed the Vindhyans in the Son and Narbada valleys were the last manifestations of true orogenic pheno- mena that have affected the Peninsular portion of India. All the disturbance that has taken place since then has been of an entirely different nature. Great land masses have sunk bodily between parallel fractures, and in the areas thus depressed a series of land or fresh-water deposits have been preserved. These are called the Gondwana series, from their being found principally in the tract so named. This series has received a large amount of attention on account of the rich stores of coal which it contains. The Gondwanas have been subdivided into several groups, those known as the Damuda and Talcher groups, and the lowest subdivision of the Damudas, the Barakar, being the richest in coal seams. (See ' The Southern Coal Fields of the Rewah Gondwana Basin,' Memoirs, Geological Survey of India, vol. xxi, p. 3.) The Barakar beds consist of sandstones and shales with numerous coal seams, and cover a large area of Rewah. The Umaria mines are excavated in this horizon.

In the Cretaceous period the sea advanced and covered a considerable area which had remained dry land since the end of the Vindhyan period, leaving limestone deposits full of marine organisms. The beds of this deposit are known as the Lametas from a ghat of this name near Jubbulpore, whence they extend westwards to Barwaha in the Indore State. An examination lately made by Mr. Vredenburg has shown that the Cretaceous beds at Bagh and the Lametas are identical and not, as has been hitherto supposed, two different rocks {Quarterly Journal, Geological Society of London, vol. xxx (1865), pp. 349-63, and Records, Geological Survey of India, vol. xx, pp. 81-92). Tiie sandstones and limestones of the Lametas yield excellent building materials. The Buddhist caves at Bagh are cut in Nimar sandstone which underlies the Bagh beds. A handsome variety of marine limestone, called coralline limestone, has been largely used in the ancient buildings of Mandu. Ores of manganese are found in the conglomerate which forms the basement of the Lametas.

The Lameta period was a short one ; and before its deposits were overwhelmed by the gigantic basalt flows of the Deccan trap, they had already been largely denuded. The whole of what is now Central India was overwhelmed by these stupendous outpourings of lava. Denudation acting upon them during the whole of the Tertiary period has removed a great part of this accumulation. The subsisting portions, consisting of successive horizontal layers, have been denuded into terraced hills. The name trappean or ' step-like ' originated from similar formations in Europe. In spite of denudation, this rock still covers a large area.

A peculiar form of alteration that seems to have been very active in former geological times produced the red-coloured highly ferruginous rock known as laterite (from later, ' a brick '), which still subsists as a horizontal layer of great thickness, capping some of the highest basaltic table-lands, while it also occurs at long distances from the present limits of the Deccan trap, showing the immensely greater area formerly covered. This rock contains a large percentage of alumina, probably suitable for the extraction of that metal.

In some regions from which the basaltic flows have been completely removed by denudation, the fissures through which the molten rock reached the surface are indicated by numerous dikes. They are especially plentiful in the Gondwanas in Rewah. Near Bagh one of the dikes is remarkable for its gigantic dimensions and colunmar structure. To the exact age of the Deccan trap there is no clue.

Along the Narbada valley there are some fresh-water beds which have long attracted attention, but have not yet been fully investigated. Their peculiar interest lies in the fact that they were certainly deposited by streams totally unrelated to the Narbada, which there is every reason to suppose is the most recent river system in India.

The recent deposits are of no very great thickness, and consist of ordinary alluvmm, gravel, and soils. An immense area in Central India is covered with the famous black cotton soil, a dark-coloured earth formed by the decomposition of the Deccan trap, which is of great richness and fertility, especially the variety found in Malwa.

' The vegetation of Central India consists chiefly of deciduous forest, characterized by the presence of a considerable number of plants that flower profusely in the hot months. Of these the most conspicuous are two species of Butea, one a tree {B. froiidosa), the other a climber {B. siiperhd). Less common but still widespread and very noticeable is the yellow-flowered ^az/^^a/ {Cochlospermum gossypmm).

The more valuable trees include teak {Tecfona graiidts), a/ija/i {Hardwickia binata), harm {Tennina/ia Chelnild), bahera {T. be/en'ca), kahtia (T. Arjuf/a), sdj (7\ tomeiitosa), bljasdl {^Pferocarpus Marsupiuvi), te/idil {Diospyros tomenfosd), finis {Oitgei?iia da/bergioides), sifsal {Dal- bergia latifolid)^ and shlsham (/>. Sissod). The natural families of Meliaceae, Steni/liaceae, Bignoniaceae, and Urticaceae are all well represented in the forests. The more shrubby forms include species of Capparis, Zizyphiis, Grezvia, Anfides/fia, Phyllantlws, Flueggeo^ Cordia, IVrighfia, Nyctanthes, Celtis, Indigo/era, F/emingia, and Desmodiitm.

The avali {Cassia aariailata) is very characteristic of outcrops of laterite amid black cotton soil, while Balanites Roxbiirghii, Cadaba indica, dk or maddr {Calotropis procera), babul {Acacia arabica), and other species are found in the cotton soil itself. The climbing plants most characteristic of this region include some species of Convolvu- laceae, many Legidninosae, a few species of Vilis, Jasminuni, and some Ctutirbitaceae. The herbaceous undergrowth includes species of Acanthaceae, Compositae, Aniarantaceae, Legtiminosae, and many grasses which, though plentiful during the monsoon period, die down completely in the hot season. Palms and bamboos are scarce.

In gardens it is possible to grow most European vegetables, and almost all the plants which thrive in the plains of Northern India, as well as many belonging to the Deccan.

All the animals common to Peninsular India are to be met with in the Agency. Up to the seventeenth century elephants were numerous in many parts of Central India, the Ain-i-Akban mentioning Narwar, Chanderl, Satwas, Bijagarh, and Raisen as the haunts of large herds. The Mughal emperors used often to hunt them, using both the khedda and pits {gar) or an enclosure {bar). The elephants from Panna were considered the best. Another animal formerly common in Malwa was the Indian lion. The last of the species was shot near Guna in 1872. Most chiefs preserve tiger and sanibar, while special preserves of antelope and chital are also maintained in some places. In Hindu States peafowl, blue-rock pigeons, the Indian roller, the sdras, and ' By Lieut.-Col. D. Train, I.M.S., of the Botanical Survey of hidia. a few other birds are considered sacred, while in many places the fish are similarly protected.

The commonest animals are mentioned in the following list. Primates : laiignr {Semitopithecus entellus), bandar {Macaais r/iesus), Carnivora : tiger {Fells tlgrls), leopard {Fells pardus), hunting leopard {Cynaelurus Judatus), mungoose {Herpestes /iningo), hyena {Hyaena striata), wild dog {Cyan dukhunensls), Indian fox { Vulpes bengalensis), wolf {Canis palllpes), jackal {Cams aureus), otter {Lutra vulgaris), black bear {Melursus urslnus). Ungulata : nilgai {Boselaphus tragocamelus), four-horned antelope {Tetracerus guadrlcornls), black buck (Antllope cervlcapra), spotted deer {Ceiims axis), sainbar {Cervus unlcolor), wild boar {Sus crlstatus). The bison {Bos gaurus) and buffalo {B. bubalus) were formerly common in the Satpura region, but are now only occasionally met with. Most of the birds which frequent the Peninsula are found, both game-birds and others. Reptllla : crocodile {Crocodllus torosus and Gavlalls gangetlcus), tortoise {Testudo elegans), turtle {Nlcorla trljuga), various iguanas and lizards. Snakes are most' numerous in the eastern section of the Agency. Three poisonous species are common : the cobra {Nala trlpudlans), Russell's viper ( Vlpera russellll), and the karalt {Bufigarus caeruleus). The Echls carlnata, a venomous if not always deadly snake, of viperine order, is also frequently seen. Of harmless snakes the commonest are the ordinar)- rat snake or dhih?ian {Zamenls mucosus), Lycodon au Ileus, Gongylophls conlcus, Tropldonotos pluinblcolor, Dendi'ophls pictus ; various Ollgodones and Slmotes and pythons {Eryx johnll) are common on the hills and in thick jungle.

Rivers and tanks abound with fish, the mahseer {Barbus tor) being met with in the Narbada, Chambal, Betwa, and other large rivers, and the rohli {Labeo rohlta) and marral or sdmval ( Ophlocephalus punctatus) in many tanks. It should be noted that the Morar river in Gwalior has given its name to the Barilius morarensls, which was first found in its waters.

Of the insect family, the locust, called tlddl or poptla, is an occasional visitor. The most common species is the red locust {Phymatea punctata). Cicadas, butterflies, moths, mosquitoes, sand-flies, and many other classes, noxious and innocuous, are met with.

The climate of Central India is, on the whole, extremely healthy, the elevated plateau being noted for its cool nights in the hot season, pro- verbial all over India. The Indo-Gangetic plain divides the highlands of Central India from the great hill system of the north, while the lofty barriers of the Vindhya and Satpura ranges isolate it from the Deccan area. These two parallel ranges, which form its southern boundary, have, moreover, a marked effect on the climate of the plateau, the most noticeable being the pronounced westerly direction which they give to the winds.

The temperature in Central India rises rapidly in April and May, when Indore, Bhopal, and the plateau area generally fall within the isotherm of 95°, while the low-lying sections are cooler, the average temperature being about 90°. The plateau enjoys the more even tem- perature, showing a difference of only 26° between the mean temperature in January and in May, while in the low-lying section the range is 32°. The diurnal range in January in the eastern part of the Agency is 26°, as compared with 29° in the plateau ; in the hot season there is no appreciable difference, but in the rains the variation is 11° in the low- lying area and 13° on the plateau. The average maximum and mini- mum temperatures in January are 77° and 48° on the plateau, and 74" and 48° in the low-lying area; in May the maximum and minimum temperatures of the plateau rise to 103° and 76°, compared with 107 and 81° in the low-lying tract. In the rains the maximum and the minimum temperatures are 83° and 71° on the plateau, and 87° and 77° in the low-lying tract. The low-lying area is thus subject to greater extremes of both heat and cold.

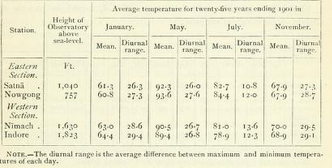

The following table gives the average temperature (in degrees Fah- renheit) in four typical months at certain meteorological stations :- —

The variation in the humidity of Central India during the year is also very marked. There are two distinct periods of maximum and mini- mum. The period of minimum- humidity during the summer months occurs in March and April on the plateau, and in April and May in the low-lying area, while in both areas November and February are the least humid of the winter months. In August in summer, and in January in winter, the humidity reaches a maximum.

The phenomenon of the hot season winds is very marked on the plateau. These winds, which begin about the middle of April, start blowing in the morning at 9 a.m., the hour of maximum diurnal pressure, and blow till 4 or 5 p.m., the time of minimum pressure.

A great fall in temperature occurs at sunset on the Malvva plateau, the nights being usually calm and cool, even in the middle of the hot season, while a gentle west wind occasionally blows. On the plateau, moreover, the current continues to retain its pronounced westerly direction ; the wind, at first dry, suddenly becoming moist, the climate, at the same time, undergoing a rapid and marked change, and the temperature falling 14 to 16 degrees. The Malwa portion of Central India is supplied principally by the Bombay monsoon current, while the eastern section of Bundelkhand and Baghelkhand shares in the currents which enter by the Bay of Bengal.

The annual rainfall on the plateau averages about 30 inches, and in the low-lying tract 45 inches. The low-lying tract gets much more rain in June than the plateau, the rain there starting earlier and falling more copiously throughout the season. The winter rains usually fall in January or the beginning of February, and are very useful to the rahi crop sowings. There is little doubt that the rainfall of the plateau area has undergone a marked decrease. Sir John Malcolm's observations (at Mhow) give an average of 50 inches, and general report points to a diminution of at least 20 inches during the last sixty or seventy years.

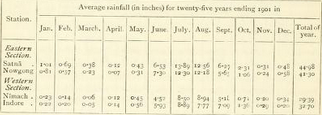

The following table gives the annual rainfall, month by month, at certain meteorological stations : —

Storms and cyclones are very rare in Central India. Serious floods occurred at Indore in 1872, considerable damage being done to houses and property. Slight shocks of earthcjuake were felt in 1898 in Bhopal and Bundelkhand.

History

The country now comprised in the Central India Agency was pro- bably once occupied by the ancestors of the Bhils, Gonds, Saharias, and other tribes which now inhabit the fastnesses of the Vindhya range. Of these early days, how- ever, we have no certain knowledge. The Rig Veda, though it records the spread of the Aryan races eastwards and westwards, never mentions the Narbada river, while the great epics the Ram- ayana and Mahabharata, and other sacred Hindu books, though they tell of a struggle between the dark-skinned aboriginal and the light-coloured Aryan, already assign the hilly Vindhyan region and the Narbada valley to the non-Aryan Pulindas and Sabaras, showing that these tribes had long since been driven out of the heart of the country.

From the early Buddhist books it appears that in Buddha's lifetime there were sixteen principal States in India, of which Avanti, with Ujeni (Ujjain) as its capital, was one, while the eastern section of Central India was comprised in the kingdoms of the Vatsas, of which KausambhT was the chief town, and of the Panchalas. Villages appear in those days to have enjoyed a large share of autonomy under their headmen, while class distinctions were not very strongly marked. Buildings were mostly of wood, only forts and palaces being of stone. There is no mention of roads, but certain great routes with their stages are given. One of these ran from north to south, from Sravasti in Kosala to Paithan in the Deccan, passing through Ujjain and MahissatT (now Maheshwar), which are mentioned as halting stations.

With the establishment of the Maurya dynasty by Chandragupta some light breaks in upon the history of Central India. Chandragupta rapidly extended his empire over all Northern India, from the Hima- layas to the Narbada, and his grandson Asoka was sent to Ujjain as viceroy of the western provinces. Chandragupta was succeeded by his son Bindusara (297-272 B.C.), who was followed by Asoka. Some years after his accession, Asoka, on becoming an ardent Buddhist, caused the erection of the famous group of stupas round Bhilsa of which that at Sanchi is the best known, and also in all probability the great stupa which formerly stood at Bharhut in Nagod. A fragment of one of his edicts has been discovered on a pillar at SanchT.

On the death of Asoka (231 b. c), his empire rapidly broke up ; and, according to the Puranas, Central India, except perhaps the most western part of Malwa, fell to the Sungas, who ruled at Pataliputra (now Patna). Agnimitra, the hero of the play Mdlavikdgnhtiitra, was viceroy of the western provinces, with his head-quarters at Vidisha (now Bhilsa). On one of the gates from the stipa at Bharhut is an inscription stating that it was erected in the time of the Sungas, Under the Sunga rule a reviyal of Brahmanism took place, and Buddhism began to lose the paramount position it had acquired under Asoka.

In the second century before the Christian era, the Sakas, a powerful Central Asian tribe, appeared in the Punjab and gradually extended their conquests southwards. One section of this horde entered Malwa, and founded a line of Saka princes who are known as the Western Kshatrapas or Satraps i^see Malwa). They soon became possessed of considerable independence, and except for a temporary check (a.d. 126) at the hands of the Andhra king of the Deccan, Vih'vayakura II (Gautamlputra), ruled till about 390, when their empire was destroyed by Chandra Gupta II.

The Guptas of Magadha rose to power in the beginning of the fourth century. An inscription at Allahabad, of Samudra Gupta, second of this line (326-75), enumerates his foes, feudatories, and allies. Among the feudatories were the nine kings of Aryavarta, one of whom, Ganapati Naga, belonged to the Naga dynasty of PadmavatT, now Narwar, where his coins have been found. Among the unsubdued tribes on his frontiers certain races of Central India are named : the Malavas, who were at this time under Satrap rule ; the Abhiras, who lived in the region between Gwalior and Jhansi, still called after them Ahirwara ; and the Murundas, who seem to have lived in the Kaimur Hills in Baghel- khand. He also took into his service the kings of the forest country, apparently petty chiefs of Baghelkhand.

Chandra Gupta II (375-413), who succeeded Samudra, was the most powerful king of the dynasty. Extending his conquests in all directions he entered Mahva, as we learn from two inscriptions at Udayagiri near Bhilsa, and destroyed the Kshatrapa power between 388 and 401, probably about 390. About 480 the regular Gupta succession ends, and the kingdom broke up, the Malwa territory being held by indepen- dent Gupta princes. Of two of these, Budha Gupta and Bhanu Gupta, we have records dated 484 and 510.

The most interesting episode of this period is the invasion of the Gupta dominions in eastern Malwa by Toramana and his son Mihirakula. These chiefs were White Huns, a section of whom had overrun Eastern Europe in a. d. 375, another horde entering India a century later. During the reign of Skanda Gupta (455-80) they were held more or less in check ; but on his death their leader Toramana pressed south, and, after seizing Gwalior and the districts round it, advanced into Malwa and soon acquired possession of the eastern portion Of that tract. From inscriptions found at Gwalior, Eran, and Mand.\sor, it appears that Toramana and his son Mihirakula held eastern Malwa for about forty years, the local princes becoming their feudatories. Mihirakula, who succeeded his father about 510, war. defeated finally in 528 by a combined attack of Nara Sinha Gupta Baladitya of Magadha and Yasodharman who ruled at Mandasor.

At the end of the sixth century Prabhakara Vardhana, king of Thanesar in the Punjab, had extended his conquests southwards ; and his younger son Harshavardhana, who succeeded an elder brother in 606, rapidly acquired possession of all Northern India and fixed his capital at Kanauj. After a reign of forty-two years he died, and his empire at once went to pieces. An interesting account of JijhotI (Bundelkhand), Maheswapura (now Maheshwar) on the Narbada, and Ujjain at this period has been given by Hiuen Tsiang. The pilgrim, who visited Kanauj in 642-3, notices the decline of Buddhism, which had been steadily losing its position since the time of the Guptas.

During the fifth and sixth centuries a number of nomad tribes, the Gurjaras, Malavas, Abhiras, and others, who were possibly descended from the Central Asian invaders at the beginning of the Christian era, began to form regularly constituted communities. During the first half of the seventh century they were held in check by the strong hand of Harshavardhana ; but on his death they became independent, and com- menced those intertribal contests which made India such an easy prey to the Muhammadan invaders of the tenth and eleventh centuries.

The Malavas and x\bhiras were early settlers in Central India. Both appear to have come from the north-west, and by about the fifth century to have occupied the districts still called after them Malwa and Ahlrwara, the country to the east of Malwa and west of the Betwa river, including Jhansi, Sironj, and the tract stretching southwards to the Narbada.

In the sixth century the powerful Kalachuri (Haihaya, or Chedi) tribe seized the line of the Narbada valley, acquiring later most of BuNDELKHAND and Baghelkhand.

From the eighth to the tenth century, by a gradual process of evolution very imperfectly understood as yet, these tribes became Brah- manized and adopted pedigrees which connected them with the Hindu pantheon, probably developing finally into the Rajput clans as we know them to-day ; the Paramaras of Dhar, Tonwars of Gwalior, Kachwahas of Narwar, Rathors of Kanauj, and Chandels of Kalinjar and Mahoba all becoming important historical factors about this time.

Recent researches appear to show that all Central India was in the eighth century under the suzerainty of the Gurjaras, a tribe who had settled in Rajputana and on the west coast in the tract called after them Gujarat. They gradually extended their power till their chief Vatsa ruled from Gujarat to Bengal. About 800 he was defeated and driven into Marwar by the rising power of the Rashtrakuta clan. The Gurjaras, however, as we learn from inscriptions at Gwalior and elsewhere, again advanced and recovered their lost dominion as far east as Gwalior, under Ramabhadra. His successor Bhoja I (not to be confounded with the famous Paramara chief who lived two centuries later) recovered all the lost territory and acquired fresh lands in the Punjab.

Two branches of the Gurjaras, who became known later as the Parihar and Paramara Rajput clans, obtained at this time the possession of Bundelkhand and Malwa respectively, holding them in fief under their Gurjara overlord. After the death of Bhoja I (885), the Gurjara power declined, owing to the rising power of the Chandels in Bundel- khand, the Kalachuris along the Narbada, and the Rashtrakutas. Taking advantage of their difficulties, the Paramara section in Mahva threw off their allegiance (915) ; and Central India was then divided between the Paramaras in Mahva, with Ujjain and Dhar as their capitals, the Parihars in Gwalior, the Chandels in Bundelkhand, with capitals at Mahoba and Kalinjar, and the Chedis or Kalachuris who held much of the present Rewah State. The history of this period is that of the alliances and dissensions of these clans, which in Central India lasted through the early days of the Muhammadan invasion, until they eventu- ally came under the Moslem yoke in the thirteenth century.

When Mahmud of Ghazni commenced his raids, the Rajputs were the rulers everywhere. Dhanga (950-99), the Chandel of Bundelkhand, had already fought with Jaipal of Lahore against Sabuktagin at Lamghan (988). In his fourth expedition Mahmud was opposed at Peshawar by Anand Pal of Lahore and a confederate Hindu army; and among those who fought round Anand Pal's standard were the Tonwar chief of Gwalior, the Chandel prince, Ganda (999-1025), and the Paramara of Mahva (either Bhoja or his father Sindhuraja). By the capture of Kanauj in 1019, Mahmud opened the way into Hindustan, and in 102 1 Gwalior fell to him. After Mahmud's death (1030), Central India was not again visited by the Muhammadans till the end of the twelfth century ; but from the time of his death until the appearance of Kutb- ud-din the history of Central India is that of the incessant petty wars which went on between the various Hindu clans. Paramara, Chandel, Kalachuri, and Chalukya (of Gujarat) waged war against one another, gaining temporary advantage each in turn, but exhausting their own re- sources and smoothing the way for the advance of the Muhammadans.

In 1 193 Kutb-ud-din entered Central India and took Kalinjar for Muhammad Ghori, and later (1196) Gwalior, of which place Shams-ud- din Altamsh was appointed governor. In 1206 Kutb-ud-dui became king of Delhi, and for the first time a. Muhanmiadan king ruled India from within, and held in more or less subjection all the country up to the Vindhyas. A period of confusion followed his death (12 10), during which the Rajputs of Central India regained the greater part of their possessions.

Altamsh finally succeeded to the Delhi throne (1210-36), and in tlie twenty-first year of his reign retook Gwalior from the Hindus after a siege of eleven months (1232). He then proceeded to Bhilsa and Ujjain, sacked the latter place and destroyed the famous temple of Mahakal, sending its idol to Delhi (1235). He was followed by a succession of weak kings, during whose reigns (1236-46) the Hindu chiefs were left much to themselves. In 1246 Nasir-ud-din succeeded. Like the others, he was a weak ruler ; but his reign is of importance on account of the energetic action of his minister Balban, who took Nar- WAR in 1 25 1, and, succeeding his master in 1266, kept the Hindu chiefs in subjection, and ruled with a firm hand, so that it was said 'An elephant avoided treading on an ant.'

On Balban's death the rule passed to the Khiljis under Jalal-ud-din, who (1292) entered Mahva and took Ujjain, and after visiting and admiring the temples and other buildings, burnt them to the ground, and, in the words of the historian, thus 'made a hell of paradise.' About this time Ala-ud-din, then governor of Bundelkhand, took Bhilsa and Mandu (1293).

In Muhammad bin Tughlak's reign (1325-51) a severe famine broke out ( 1 344) ; and the king resting at Dhar on his way from the Ueccan found that 'the posts were all gone off the roads, and distress and anarchy reigned in all the country and towns along the route,' while the anarchy was augmented by the dispatch of Aziz Hamir as governor of Malwa, who by his tyrannous actions soon drove all the people into rebellion. In the time of Firoz Shah (1351-88) the process of dis- integration commenced, which was completed in the time of Tughlak Shah II. The land was divided into provinces governed by petty rulers, Malwa, Mandu, and Gwalior being held by separate chiefs.

The history of Central India now becomes largely that of Malwa. The weak Saiyid dynasty, who held the Delhi throne from 1414 to 145 1, were powerless to reduce the numerous chiefs to order, and Mahmud of Malwa even made an attempt to seize the Delhi throne (1440), which was, however, frustrated by Bahlol Lodi. It is worth while noting, in regard to this weakening of Musalman rule, how Hindu and Muhammadan had by this time coalesced. ^Ve find the Hindu chiefs employing Muhammadan troops, and Mahmud of Malwa enlist- ing Rajputs. Some sort of order was introduced under the Lodis (1451-1526) ; but they had no great influence, except in the country immediately round Delhi, though Narwar was taken by Jalal Khan, Sikandar's general (1507), and Ibrahim Lodi captured the Badalgarh outwork of Gwalior (15 18).

The emperor Babar (1526-30) notes in his memoirs that Malwa was then the fourth most important kingdom of Hindustan (being a part of Gujarat under Bahadur Shah), though Rana Sanga of Udaipur had seized many of the provinces that had formerly belonged to it. Babar's forces took Gwalior (1526) and .Chanderi (1527), and later he visited Gwalior (1529), of which he has left an appreciative and accurate account. Humayun defeated Bahadur Shah at Mandasor (1535), but in 1540 was himself driven from India by Sher Shah.

Sher Shah, the founder of the Suri dynasty (1539-45) was a man of unusual ability, and soon reduced the country to order. He obtained possession of Gwalior, Mandu, Sarangpur, Bhilsa, and Raisen, (1543-4), making Shujaat Khan, his principal noble, viceroy in Malwa, Islam Shah, Sher Shah's successor, made Gwalior the capital instead of Delhi, and it continued to be the chief town during the brief reigns of the remaining kings of this dynasty.

Huniayun regained his throne in 1555, but died within the year, and was succeeded by Akbar, who in 1558 entered Central India, and taking Gwalior, proceeded against Baz Bahadur, son of Shujaat Khan, then holding most of Malwa, and finally drove him out in 1562. Ujjain, Sarangpur, and Slpri were soon in Akbar's hands, thus com- pleting his hold on Malwa, while in 1570 Kalinjar was surrendered by the Rewah chief, and all Central India thus came under his sway. In 1602 Bir Singh Deo of Orchha, in Bundelkhand, murdered Abul Fazl at the instigation of prince Salim (Jahangir), and in revenge Orchha was taken.

In Shah Jahan's reign, Jhujhar Singh, the Raja of Orchha, rebelled and was driven from his State (1635), which formed part of the empire till 1641.

In 1658, during the struggle for the throne, Aurangzeb and Murad defeated Jaswant Singh at Dharmatpur, now F'atehabad, near Ujjain, and thus opened the road to Agra. During this period the Marathas, who had already begun to desert the plough for the sword in the time of Jahangir, first crossed the Narbada (1690), and plundered the Dharampurl district (now in Dhar), while in 1702-3 Tara Bai sent expeditions to plunder as far as Sironj, Mandasor, and the Subah of Malwa and the environs of Ujjain.

Though the Marathas had entered Malwa as early as 1690, it was not till the reign of Muhammad Shah (1719-48) that they obtained a regular footing in this part of India. So rapidly did their power increase under the tacit, if not active, support of the Hindu chiefs, that in 1 71 7 Maratha officers were collecting chauth under the very eyes of the imperial sfibahddrs. In 1723 the Nizam, at this time governor of Malwa, retired to the Deccan ; and the Peshwa BajT Rao, who had determined to destroy the Mughal power, at once strengthened his position across the Narbada by sending his generals (1724), notably Holkar, Sindhia, and the Ponwar, to levy dues in Malwa. In 1729 the oppressive action of Muhammad Khan Bangash in Bundelkhand induced Chhatarsal of Panna to call in the aid of the Peshwa, who thus obtained a footing in eastern Central India. The Pesliwa's power was finally confirmed in Malwa in 1743, when he obtained, through the influence of Jai Singh of Jaipur, the formal grant of the deputy-governor ship of Malwa. In 1745, at the time of Ranoji Sindhia's death, the whole of Malwa, estimated to produce 150 lakhs of revenue, was, with small exceptions, divided between Holkar and Sindhia. Lands yield- ing ID lakhs were held by various minor chiefs, of whom Anand Rao Ponwar (Dhar) was the most considerable. From this time Central India remained a province of the Peshwa until the fatal battle of PanTpat in 1761 broke the power of the IVlaratha confederacy, and Central India was divided between the great Maratha generals. Three years later the battle of Buxar made the Mughal emperor a pensioner of the East India Company ; and though they had a severe struggle with the great Central India chiefs, Holkar and Sindhia, the British henceforth became the paramount power in India.

Comparatively speaking, Central India was at peace from 1770 to 1800. The territories of Holkar were, during most of this period, under Ahalya Bai (1767-95), whose just and able rule is proverbial throughout India, while till 1794 the possessions of Sindhia were con- trolled by the strong hand of Mahadji. The great influence of Tukoji Holkar (1795-7), who succeeded Ahalya Bai, restrained young Daulat Rao Sindhia and kept things quiet, till on Tukoji's death (1797) the keystone was removed and the structure collapsed. Central India was soon plunged into strife, and all the advantages which the land had derived from forty years of comparative peace were lost in a few months.

Troubles in Bombay had necessitated proceedings against Mahadji Sindhia, who was intimately concerned with them ; and Gwalior was taken by Major Popham (1780), and Ujjain threatened by Major Camac, which caused Sindhia to agree to terms (October, 1781). The next year, Sindhia's independence of the Peshwa was recognized in the Treaty of Salbai (1782), and he at once commenced operations in Hindustan. Mahadji Sindhia died in 1794, and his successor, Daulat Rao, had by 1798 become all-powerful in Central India, when the appearance at this moment of Jaswant Rao Holkar, with the avowed intention of reviving the fallen fortunes of his house, soon plunged the country into turmoil. Now commenced that period of unrest, still known to the inhabitants of Central India as the 'Gardl-ka-wakt,' which reduced the country to the last state of misery and distress.

A clear proof of the anarchy which prevailed in Central India at this time is given by the ease with which Jaswant Rao Holkar was able in the short space of two years to collect a body of 70,000 men — Pindaris, Pathans, Marathas, and Bhils — who were tempted to join his standard solely by the hope of plunder, and with whose assistance he proceeded to devastate the country. The capture of Indore (1801) and wholesale massacre of its inhabitants by Sarje Rao Ghatke, the father-in-law of Sindhia, was no check on Holkar, whose victory at Poona (1802) sent him back with renewed energy to ravage Malwa.

The non-interference system pursued by Cornwallis, followed by Barlow's policy of 'disgrace without compensation, treaties without security, and peace without tranquillity,' allowed matters to pass from bad to worse. To the hordes which plundered under Amir Khan and Jaswant Rao Holkar were added the bodies of irregular horse from British service which had been indiscriminately disbanded at the end of Lord Lake's campaign. In 1807 Bundelkhand was in a state of fer- ment. Parties of marauders scoured the country, and numerous chiefs, secure in their lofty hill forts, defied the British authority. As soon, however, as they saw that the policy had changed and that the British intended to interfere effectively, most of them surrendered, but the chiefs of Kalinjar and Ajaigarh only submitted after their forts had been taken by assault. Li 181 2 the Pindaris began to increase to an alarming extent ; and supported by vSindhia and Holkar and aided by Amir Khan, their bands swept Central India from end to end, passing to and fro between Malwa and Bundelkhand, and even crossins the border into British India.

At this juncture, Lord Hastings was appointed Governor-General. Ten years of practically unchecked licence had enormously increased the numbers of the marauders. About 50,000 banditti were now loose in Central India, and the confusion they produced was augmented by the destructive expedients adopted by Holkar, who sent out subahddrs to collect revenue, accompanied by large military detach- ments, which were obliged to live on the country, while at the same .time extorting funds for the Darbar. By 181 7 the disorganization had reached a climax. At last Lord Hastings received permission to act. Rapidly forming alliances with all the native chiefs who would accept his advances, he ordered out the three Presidency armies, which gradually closed in on Central India. Sindhia, who had originally promised his aid, now showed signs of wavering, but a rapid march on Gwalior caused him to come to terms, while Amir Khan at once sub- mitted, and dismissed his Afghan followers. The army of Holkar, after murdering the Rani, marched out to oppose the British, but was defeated at Mehidpur (1817). The Pindari leaders, Karim, Wasil Muhammad, and Chltii, were either forced to surrender or hunted down, and the reign of terror was over.

These military and political operations were remarkable alike for the rapidity with which they were executed and for the completeness of their result. In the middle of October, 181 7, the Marathas, Pin- daris, and Pathans presented an array of more than 150,000 horse and foot and 500 cannon. In the course of four months this formidable armament was utterly broken up. The effect on the native mind was tremendous, and a feeling of substantial security was diffused through Central India. So sound, moreover, was the .settlement effected, under the superintendence of Sir John Malcolm, that it has required but few modifications since that time.

The next few years were spent in settling the country and repopu- lating villages. One of the principal means of achieving this was by granting a guarantee to small landhcjlders that their holdings would be assured to them, on the understanding that they assisted in pacifying the districts in which they lived. This guarantee, which secured the small Thakurs from absorption by the great Darbars, acted like magic in assisting to produce order. In 1830 operations were commenced against the Thags, whose murderous trade had been greatly assisted by the late disorder, but who, under Colonel Sleeman's energetic action, were soon suppressed.

Affairs in the State of Gwalior now became critical. Daulat Rao Sindhia had died childless in 1827, and two successive adoptions of young children followed. Disputes arose between the regent and the Rani. The army sided with the Rani, and the state of affairs became so serious that the British Government was obliged to send an armed force. Fights took place on the same day at Maharajpur and Panniar (December 29, 1843), in which the Gwalior army was destroyed. The administration of the State was reorganized and placed under a Political ofificer, whose authority was supported by a contingent force of 10,000 men.

The various sections which now compose the Central India Agency were at first in charge of separate Political officers. Residents at Indore and Gwalior dealt direct with the Government of India, and Bundel- khand and Baghelkhand were independent charges. In 1854 it was decided to combine these different charges under the central control of an Agent to the Governor-General. The Bundelkhand and Baghel- khand districts were added to Malwa, and the whole Agency so formed was placed under Sir R. Hamilton, at that time Resident at Indore, as Agent to the Governor-General for Central India.

The first serious outburst during the Mutiny in Central India took place on June 14, 1857, among the troops of the Gwalior Contingent at MoRAR, whose loyalty had been doubted when the first signs of trouble appeared. Sindhia was still only a youth, but luckily there were present at his side two trusty councillors, Major Charters Macpherson, the Resident, and Dinkar Rao, the minister. Major Macpherson, before he was forced to leave Gwalior, managed to impress on Sindhia the fact that, however bad things might appear, the British would win in the end, and that it was above all necessary for him to do his best to prevent the mutinous troops of the Contingent leaving Gwalior territory, and joining the disaffected in British India.

On June 30 the Indore State troops sent to guard the Residency mutinied, and Colonel Durand, Officiating Agent to the Governor- General, was obliged to retire to Sehore and finally to Hoshangabad. Outbreaks also took place at Nlmach (June 3), Nowgong (June 10), Mhow (July 8), and Nagod (September).

In October, 1857, the Central India campaign commenced with the capture of Dhar (October 22). In December Sir Hugh Rose took command, and ousting the pretender Firoz Shah, who had set up his standard at Mandasor, took the forts of Chanderi, Jhansi (March, 1858), and GwALiOR (June). The two moving spirits of the rebelUon in Central India were the ex-RanI of Jhansi, Lachml Bai, and Tantia Topi, the Nana Sahib's agent. The Rani was killed fighting at the head of her own troops in the attack on Gwalior, and Tantia Topi after a year of wandering was betrayed by the Raja of Paron and executed (April, 1859). The rising thus came to an end, though small columns were required to operate for a time in certain districts.

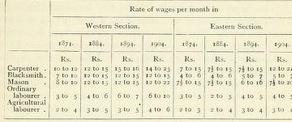

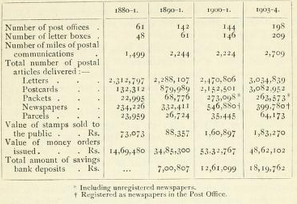

After the excitement of 1857-9 had died away, the country soon returned to its normal condition, and the history of Central India from this time onwards is a record of steady general improvement. Com- munications have been improved by the construction of telegraphs, high roads, and railways, and by the development of a postal system, while trade has been facilitated by the abolition of transit dues. Closer supervision has led to great reforms in the systems of administration in the various States, which were everywhere crude and unsatisfactory. A regular procedure has been laid down for the settlement of boundary disputes, and education has been fostered. Still, the course of progress has not been uninterrupted. Severe famines, and more lately plague have ravaged the country from time to time, and cases have occurred where mismanagement and even actual crime have led to the removal of chiefs.

The archaeological remains in the Agency are considerable, including old sites, buildings of historical and architectural importance, ancient coins, and epigraphic records. Little is really known as yet about most of the places, which require more systematic investigation, especially ancient sites, such as those of Old Ujjain and Beshnagar. Many of the old Hindu towns have since been occupied by Muham- madans, as for instance Dhar, Mandasor, Narwar, and Sarangpur, and are consequently no longer available for thorough research, though, as at Dhar and Ujjain, chance sometimes brings to light an old Hindu record which has been used in constructing a Muhammadan building.

The principal places at which remains and buildings of interest exist are Ajaigarh, Amarkantak, Bagh, Baro, Barwani, Bhojpur, ChanderI, Datia, Dhamnar, Gwalior, Gyaraspur, Khajraho, Mandu, Nagod, Narod, Narwar, Orchha, PatharT, Rewah, Sanchi, Sonagir, Udayagiri, Udayapur, and Ujjain.

Ancient coins have been found in many of the old sites, ranging from the early punch-marked series to those of the local chiefs and the Mughals. The epigraphic records found are also numerous. The earliest with dates are those inscribed on the railings and gates of the stupas at SanchT and Bharhut, belonging to the first years of the Christian era. Next in chronological order follow the Gupta inscrip- tions, of which the earliest is dated in the year 82 of the Gupta era (a. D. 401), tlie latest on some copperplates from Ratlam of the year 320 (a. D. 640). A record from Mandasor, dated in the year 493 of the Malwa rulers (corresponding to a. d. 436), is important, as in con- junction with other similar records it has been instrumental in proving the identity of the era of the lords of Malwa with the Vikrama Samvat of the present day.

The various records, both inscriptions on stone and copper-plate land grants, have afforded much information regarding the history of the dynasties which from time to time ruled in Central India, notably the Guptas of Magadha of the fourth to the sixth century, the Rajput chiefs — the Paramaras of Malwa, the Chandels of Bundelkhand, the Kalachuris of Baghelkhand — the rulers of Kanauj of the ninth to the fifteenth century, and the subsequent Muhammadan rulers.

Central India is unusually rich in architectural monuments, especially of Hindu work, which afford probably as complete a series of examples of styles from the third century b. c. to the present day as can be seen in any one province in India. In Muhammadan buildings the Agency is less rich.

The earliest constructions in Central India date from the third century b.c. and are Buddhist. They include stupas or monumental tumuli, often containing relics of famous teachers of that faith, chaitya halls or churches, and vihdras or monasteries. A considerable number of stupas are still standing in Central India, many being grouped round Bhilsa, and the finest of the series being the Sanchi Tope. This and another, which formerly stood at Bharhut in Nagod, were erected in the third century b.c. Of the chaitya hall numerous rock-cut examples exist, but none is of great age. The oldest chaitya hall in Central India is represented by the remains standing to the south of the Sanchi Tope, which are of special interest as constituting the only structural building of its kind known in all India. The rock-cut examples which date from about the sixth to the twelfth century exemplify the transitions through which this class of building passed, those at Bagh and Dhamnar being about two centuries older than those at Kholvi, a place situated close to Dhamnar, but just outside the Central India Agency in the State of Jhalawar. The vihdra or monastery is also met with at these places, being in some cases attached to a chaitya hall, forming a combined monastery and church. Probably monolithic pillars formerly stood beside most of these three classes of building ; the remains of one bearing an edict of Asoka were found at Sanchi.

The buildings which follow these chronologically have been not very happily named Gupta, as the name has obscured their connexion with those just dealt with. They are represented by both rock-cut and structural examples, the former existing at Udavagiri, and at Mara in Rewah. In two of the caves at the first place inscriptions of A.D. 401 and 425 have been found, but many of the caves may well be older. The structural temples of this class are numerous, those at SanchI, Nachna in Ajaigarh, Paroli in Gwalior, and Pataini Devi in Nagod being good examples, while many remains of similar buildings lie scattered throughout the Agency.

Though many buildings of the so-called Jain style have disappeared, the Gyaraspur temples, the earliest buildings at Khajraho, the later temples at the same place, and the Udayapur temple give a sufficiently consecutive chain leading up to the modern building of the present day with its perpendicular spire and square body.

Numerous examples of this mediaeval style (of the eighth to the fifteenth century) lie scattered throughout Central India in various stages of preservation, those at Ajaigarh, Baro, Bhojpur, and Gwalior being important. The later developments of the sixteenth century are to be seen at Orchha, Sonagir, and Datia, and of the seventeenth century to the present day in almost any large town. The modern temple as a rule has little to recommend it. The exterior is plain and lacks the light and shade produced by the broken surface of the older temples, and the general effect is marred by the almost perpendicular spire, the ugly square body often pierced by foliated Saracenic arches and surmounted by a bulbous ribbed Muhammadan dome; while all the builder's ingenuity appears to be lavished on marble floors, tinted glass windows, and highly coloured frescoes. Temples of this class abound, those at Maksi in Gwalior and several in Indore city affording good examples of the modern building. The chhafri of the late Maharaja Sindhia at Gwalior is perhaps as good an example of modern work as any.

Muhammadan religious architecture is not so well represented in Central India. The earliest building of which the date is certain is the mosque near Sehore, built by a relative of Muhammad bin Tughlak in 1332. The most important buildings are those at Dhar and Mandu, where numerous mosques, tombs, and palaces were erected by the Malwa kings between 1401 and i53r. These are in the Pathan style, distinguished by the ogee pointed arch, built with horizontal layers of stone and not in radiating courses, which shows that they are Muham- madan designs executed by Hindu workmen. These buildings are ordinarily plain ; and the pillars, when not taken directly from a Hindu or Jain edifice, are simple and massive, the Jama Masjid at Mandu being a magnificent example of this style. Scattered throughout Central India are numerous small tombs in the Pathan style, to be seen in almost any place which Muhammadans have occupied.

Of Mughal work the best example is the tomb of Muhammad Ghaus in Gwalior, which is a very fine building in the early Mughal style of Akbar and Jahangir, with the low dome on an octagonal base, and a vaulted roof ornamented with glazed tiles.

Of modern Muhammadan work the only example of any size is the new Taj-ul-Masajid at Bhopal, not yet completed. The plan is that of the great mosque at Delhi, though, owing to the weakness of the foundations, the flanking domes have been omitted. The general effect is fine ; but the carving is poor, being too slight for the general design, and the pillars, which are massive, would have been better without it. All the modern buildings have the heavily capped and ribbed dome common to the later Mughal style. Muhammadan build- ings also exist at Sarangpur, Ujjain, (iwAUOR, Gohad, Narwar, and Chandkri. Muhammadan domestic architecture is not repre- sented by any important edifices, except the palaces at Mandu and the water palace at Kaliadeh near Ujjain,

Of the domestic architecture of the Hindus there are few examples of note. The finest building of this class is the fifteenth-century palace of Raja Man Singh at Gwalior, its grand facade being one of the most striking features of the old fort, while at Orchha and Datia there are two majestic piles, erected by Raja Bir Singh Deo of Orchha in the seventeenth century.

There is little modern work that merits much attention. In most cases, such as the palaces erected by chiefs of late years, either small attention has been paid to the design, or else the Hindu, Muham- madan, and European styles have been mingled, so as to produce a sense of incongruity and unfitness, as in the mosque-like palace at Ujjain. The most noteworthy building of this class is the Jai Rilas palace at Gwalior, which is designed on the model of an Italian palazzo, but is marred by the unfortunate use of Oriental ornamental designs ; the college and hospital at the same place are more successful. The ordinary dwelling-houses of the well-to-do have few pretensions to style, though a marked improvement is noticeable in the increased number of windows introduced. Of F^uropean buildings, the Residency House at Indore and the Daly College are the only structures of any size, but architecturally they have nothing to recommend them. The most picturesque buildings are the churches at Sehore and Agar.

Throughout Central India there are a large number oi ghats (bathing- stairs) and dams, some of considerable age and great size. The colossal dams at Bhojpur are the finest, but many others exist, as at Ujjain, Maheshwar, and Charkhari. Bundelkhand is especi- ally rich in them. Examination shows that they were built to form tanks, not for irrigation, but as adjuncts to temples, palaces, or favourite resorts. Their employment for irrigation is invariably a later development.

Population

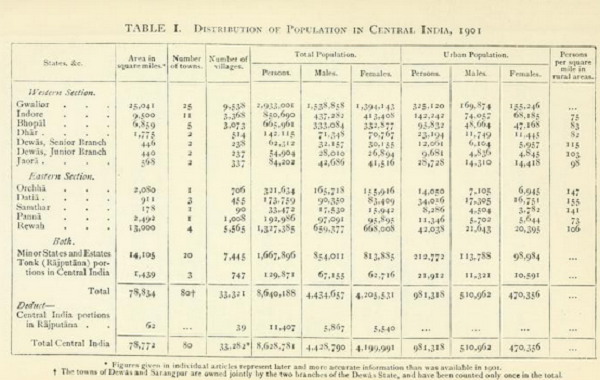

The population of Central India at the three regular enumerations was: (1881) 9,261,907, (1891) 10,318,812, (1901) 8,628,781 \ The average density (109 persons per square mile) varies markedly in the different natural divisions. In the low-lying tract, °^" ■ forming the eastern part of the Agency, the density

is 172 per square mile, in the plateau 102, and in the hilly tracts only 74.

The Agency contains 63 towns with 5,000 or more inhabitants, besides 17 of which the population through famine and other causes had fallen below that figure since 1891. Of the towns, 49 are situated on the western side of the Agency, and only 14 in Bundelkhand and Baghelkhand. The largest city is Lashkar, the modern capital of Gwalior, with a population of 89,154; Indore (86,686) and Bhopal (77,023) come next in importance. Of the 33,282 villages, 30,058 have a population of less than 500, the average village containing only 230 persons. The size of the village is greater in the low-lying tract, where the average rises to 313. The village in Central India, when of fair size, consists as a rule of a cluster of small habitations surrounding a large building, the home of the Thakur who holds the land.

The population fell by 16 per cent, during the last decade, owing mainly to the two severe famines of 1896-7 and 1 899-1 900. The decrease took place, however, only in the rural population, the urban population rising by 18 per cent., due chiefly to the opening of new railways and consequent increase of commerce.

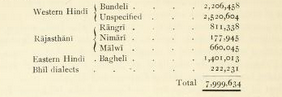

Central India gains little from immigration. Of the total population enumerated in 1901, 92 per cent, were born within the Agency. This fact is supported by the language figures, which show 93 per cent, speaking local dialects. Such immigration as takes place comes chiefly from the United Provinces, and flows into Bundelkhand and Baghel- khand, amounting to 47 per cent, of the total immigration, Rajputana supplying 26 per cent. On the whole, Central India gained about 90,000 persons as the net result of immigration and emigration. Internally there is very little movement.

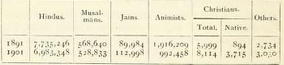

The age statistics show that the Jains, who are the richest and best- nourished community, live the longest, while the Animists and Hindus show the greatest fecundity. The age at marriage varies with locality, the same sections of the community in different parts marrying their children at somewhat varying periods. Most males under five years of age are married in the low-lying tract, while the statistics show that child-marriage is becoming popular among the Bhils and allied tribes.

No vital statistics are recorded in Central India, but from the census figures it is apparent that infant mortality increased in the period

^ This figure includes the population of parts of Rajputana, but excludes that of portions of Central India States in other Agencies, &c., see p. 322. 1895-9, which involved two famines and several bad agricultural years. Plague has also very materially affected the population.

Except for an occasional local outbreak of cholera and small-pox, Central India was free from serious epidemics till 1902, when plague appeared. The first case (except for an isolated instance in 1897) was reported in 1903 from the village of Kasrawad in the Nimar district of Indore State, and the epidemic spread thence to Ratlam, and finally to Indore city, the Residency area, and Mhow cantonment. The registra- tion of deaths from this cause was very incomplete, but an idea of its virulence may be gained from the figures for these places.

In Indore city the deaths recorded in three months during 1904 were 10 per cent, of the population ; in the Residency area the total number of deaths in 1903 was 966, or 9 per cent. ; in Mhow, 5,136, or 14 per cent. Other places of importance which have suffered from plague are Lashkar, Jaora, Bhopal, Sehore, Dewas, Nimach, Mandasor, Shajapur, and Agar. In the districts the attacks were less violent, as a rule, though here and there individual villages were very severely visited. The actual loss of life, added to the emigration consequent on fear ot infection, has seriously affected agricultural conditions in Malwa by reducing the population. Inoculation was at first looked on with the greatest suspicion, but ultimately a large number of persons were treated.

Female infanticide in Central India was first reported on by Mr. Wilkinson in 1835. He found that not less than 20,000 female infants were yearly made away with in Mahva alone. No attempt at concealing the practice was made, and a careful examination showed that 34 per cent, of girls born were killed. In 1881 attention was called to the prevalence of this custom in Rewah, and special measures were taken to cope with it. The census figures of 1901, however, give no proof that the custom is now a general one.

The total number of persons affected by infirmities in Central India in 1 90 1 was 3,180 males and 2,272 females. This included 5 males and 2 females insane, 19 male and 13 female deaf-mutes, 41 males and 35 females blind, 6 male and 4 female lepers, in every 100,000 of the population. Insanity is more prevalent in the plateau and low-lying tracts than in the hills, a fact possibly due to the inhabitants of the jungle tracts being but little addicted to the use of opium.

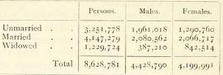

Central India in 1901 contained 4,428,790 males and 4,199,991 females. The ratio of women to 1,000 men was 896 in 1881, 912 in i89i,and 948 in 1901, being 950 in towns and 920 in villages. Of the natural divisions, the hilly tracts have the most females, about 9,900 to every 10,000 males, while the plateau and low-lying divisions have about 9,400 and 9,300 respectively. The hilly tracts thus contain between 5 and 6 per cent, more women than the other two tracts. The figures for the different political charges vary • Baghelkhand alone shows an excess of females.

Marriage and cohabitation are not simultaneous, except among the animistic tribes of the hilly tracts. Out of the total population in 1901, 3,080,562 males and 2,066,717 females were married, giving a proportion of 9,933 wives to 10,000 husbands. In a country where marriage is considered obligatory it is interesting to note that 44 per cent, of the males of all ages and 31 percent, of the females are unmarried. In the widowed state a large difference is noticeable between males and females, the prohibition to remarry raising the figure for females to 20 per cent., that for males being 9 per cent. Most men between 20 and 30 are married. No great rise takes place in the number of married till after fifteen years of age, the difference between the 1 5-20 and 20-40 periods being about 2,700 persons per 10,000. Girls marry earlier.