Chakma

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

Contents |

Chakma

Tradition of origin

Tsakma, Tsak, Thek (Burm.), a Lohitic1 tribe of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Major Lewin groups them with the Khyoungtha, or tribes who live along the river courses, as distin¬guished from the Toungtha, whose settlements are confined to the hills. Concerning this division into river and hill peoples, which is believed to have originated with the Arakanese, Hen A. Griinwede12 remarks that it " not only supplies a good outward distinction, but is moreover fully justified, inasmuoh as it at the same time preserves intact the division according to descent." Herr Virchow, however, observes that "these divi¬sions, based as they are on the localitie of the tribes along the rivers or on the hills, must by no means be supposed to represent either genetic or de facto homogeneous groups." The traditions regarding the origin of the Chakrnlis are conflicting, and allege (I)

I From loltita, 'red,' a name of the Brahmaputra, believed by Lassen to have reference to the east and the rising sun. (Ind. Alt. i, 667, note.) F. MUller (Allgemel~ne Etltnographie, p. 405) includes the Burmese and tho tribes of the Chittagong Hill Tracts and Arakan uncleI' the term Loltita¬y olker. 2 Summary Notice of the Hill Tribes, in Riebeck's Chittagong Hill Tribes, translated by Keane. that they originally oame from tho Malay Peninsula, (2) that their ancestors were Chaus-bansi Kshatriyas or Champanflgar in Hindustan, who invaded the Hill Tracts about the end of the 14th century, settled there, and intermanied wit.h the people of the country; (3) that they are the descendants of the survivors of a Mogul army sent by the Vazir of Chittagong to attack the King of Arakan. Owing, it is said, to the Vazir declining the food offered to him by a Buddhist Phoongyee whom he met on the way, his army was defeated by art magic and his soldiers became slaves to the King of Arakan, who gave them land and wives in the Hill Tracts. In support of this tradition Major Lewin refers to the fact that the Chakma Rajas from 1715 to 1~30 bore the title Khan. This, however, clearly proves little, as the title is borne by many Hindus, and nothing is more probable than that the Raja of a wild tribe should have bonowed it from the Mahomedan rulers of Chittagong.

The evidence at present available does not appear to warrant any more definite conclusion than that the Chakmas are probably a people of Arakanese origin, whose physical type has been to some extent modified by intermarriage with Bengali settlers. 'l'his view, though deriving some support from the faot that the tribe have only lately abandoned the nse of an Arakanese dialect, possesses no scientific value, as for all we know the settlement in Arakan may be of very recent date, and the true affinities of the tribe oan only be determined by a thorough examination of their physical characteristios. Dr. Riebeok's measurements comprised only three subjects a number insufficient, as Hen Virchow points out, to admit of the calculation of an average which shall represent an approximation to the true physioal type of the tribe.l

Inernal structure

The Chakmas are divided into three sub-tribes-Chakma, Doingnak, and Tungjainya or Tangjangya. 'The Doingnaks are believed to have broken off from the parent tribe about a century ago, when Jaun Baksh Khan was Chief, in consequence of his having ordered them to intermarry with the other branohes of the tribe. This innovation was violently disapproved of, and many Doingnaks abandoned their homes on the Karnaphuli river and fled to Arakan. Of late years some of them have returned and settled in the hills of the cox's Bazar subdivision. When Captain Lewin wrote, the Doingnaks spoke an Arakanese dialeot, and had not yet acquired the corrupt form of Bengali which is spoken by the rest of the Chakmas. The Tungjainya sub-tribe are said to have oome into the Chittagong Hills from Al'akan as late as 1819, when Dharm Baksh Khan was Chief. A number of them, however, soon returned to Arakan in consequence of the Chief's refusal to recognise the claims of their Jeader, Phapru, to the headship of the sub-tribe. A,bout twenty years ago the elders of the Tungjainya sub-tribe still spOKe Arakanese, while the younger generation were following the example

1 Since this was written onc hundred specimens of the Chakma tribe have been measured under my supervision. The average cephalic index deduced from this large number of subjects is 84,.5, and the average naso•malar index 106'4. A tribe so markedly brachy.cephalic and platyopic must clearly be classed as Mongoloid. of the Chakmas and taking to Bengali. Ontsidersare admitted into the tribe. They must spend seven days in the priest's honse, and then give a feast to the tribe, at which certain mantras arc repeated to sanctify the occasion, and fowls and pigs are killed. Persons so admitted are almost invariably natives of the plains who have become attached to Chakma women. Although fully recognised as members of the tribe for social purposes, they would be distin-guished by the designation BangcHi, but their offspring will rank in every respect as Chakmas.

A list of the exogamous septs (goza) of the Chakmas and Tungjainiyas will be found in Appendix I . I have been unable to obtain a list of the septs of the Doingnaks. It will be observed that many of the septs are of the eame type as those found among the Limbus and Tibetans ; that is, the names record some curious adventure or personal peculiarity of the supposed ancestor of the sept. Others, again, are territorial ; only, instead of taking their names from a village or a tract of country, they follow the names of rivers. The sept name descends in the male line, and the rule of exogamy based upon it is lmilateral; that is, while a man is forbidden to marry a woman belonging to his own sept, there is nothing, so far as the rule of exogamy goes, to prevent him from marrying a woman belonging to his mother's sept. The prohibition arising from the sept name is therefore supplemented by forbidding men to marry the following relatives and their descendants :-Step-mother, mother's sister, sister, sister's daughter, mother's brother's daughter, father's sister's daughter, wife's elder sister. After his wife's death a man may marry 1er younger sister.

Among the chakmas, as perhaps among the Greeks and Romans in the beginning of their history; the sept is the unit of the tribal organization for certain public purposes. Each sept is presided over by an hereditary dewan (among the Tungjainiyas called ahUn) , who represents the family of the founder. This officer collects the poll-tax, keeps a certain proportion himself, and pays the remainder with a yearly offering of first fruits to the Chief of the tribe. When a wild animal fit for food is killed, he has a right to a share in the carcass. He also decides the disputes, mostly matrimonial or more or less connected with women, which make up most of the litigation within the tribe, and divides the fines with the Chief. Where the sept is large and scattered, the deWcln has subordinate headmen (kllqja) to assist him. These are exempt from poll-tax and begari or compulsory labour, but must make to the dewin a yearly offering of one measure of rice, one bamboo vessel (c1tunga) of spirits, and a fowl.

Population

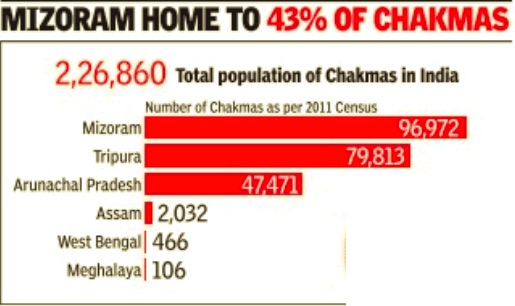

See graphic: Chakma population in India in 2011, state-wise

Marriages

I quote at length Major Lewin'sl graphic and sympathetic description of the marriage customs of the Chakmas :" Child-marriages among the Chakmas, or indeed among the hill people in general, are unknown. there is no fixed time for getting married. Some of the young men indeed do not marry until they reach the age of 24 or 25: after that age, however, it is rare to see a man unmarried. Marriage is after this fashion: Father, mother, and son first look about them and fix upon a bride. This indispensable preliminary accomplished, the parents go to the house where their intended daughter-in-law resides, They take with them a bottle of spirits (this is an absolute necessary in every hill palaver). The matter will at first be opened cautiously. The lad's father will say, 'That is a fine tree growing near your house; I would fain plant in its shadow.' Should all go well, they retire after mutual civilities. Both in going and coming omens are carefully observed, and many a promising match has been put a stop to by un¬favourable auguries. A man or woman carrying fowls, water, fruit, or milk, if passed on the right hand, is a good omen and pleasant to meet with; but it is unfavourable to see a kite or a vulture, or to see one crow all by himself croaking on the left hand. if they are unfortunate enough to come upon the dead body 01 any animal on their road, they will go no further, but at once return home and stop all proceedings. Old people quote numerous stories to show that the disregard of unfavourable omens has in former times been productive of the most ruinous consequences.

"By the time a second visit is due the relatives on both sides have been consulted; and if all has progressed satisfactorily and there are no dissentient voices, they go accompanied by some of the girls of the village, taking with them presents of curds and bind grain, and fum'a, a sweet fermented liquor made from rice. Then a day is settled (after the harvest is a favourite time), and a ring of betrothal is given to the bride, Now, also, is arranged what price the young man is to pay for his wife; for the Chakmas, in contradistinction to all our other tribes, buy their wives. The ordinary price is Rs. 100 to Rs, 150. On the marriage day a lal'ge stock of provisions is laid in by both houses, A procession of men and women start from the bedegroom's village with drums and music to fetch home the bride. The parents of the bridegroom present their intended daughter with her marriage dress, No ceremony, however, is performed; and the bride, after a short interval, is taken away, accompanied by all the relatives, to her new home.

"On arriving all enter the house, and the bride and the bride-groom sit down together at a small table-the bride on the left hand of her husband. On the table are eggs, sweetmeats, rice, and plantains, all Jaid out on leaf platters, The best man (sowalla) sits behind the bridegroom, and the bride has a representative brides-maid (sowalii) behind her. These two then bind around the couple a muslin scad, asking. 'Are all willing, and shall this be accomplished.' Then all cry out, 'Bind them, Bind them,' so they are bound. The married pair have now to eat together, the wife feeding the husband and the husband the wife; and as at this stage of the ceremony a great deal of bashfulness is evinced, the bridesmaid and best man raise the hands of their respective charges to and From each other's mouths, to the intense enjoyment and hilarity of everyone present. After they have thus eaten and drunken, an elder of the village sprinkles them with river-water, pronounces them man and wife, and says a chann used for fruitfulness. The couple then retiro, and the guests keep it up until an early hour on the following morning. The next day, at the morning meal, the newly married come hand in hand and salute the elders of the families. The father of tho bride generally improves this occasion by addressing a short lecture to his son-in-law on the subject of marital duties. 'Take her,' he says; , I have given her to you; but she is young and not acquainted with her household duties. If therefore at any time you come back from the jltum and find the rice burnt, or anything else wrong, teach her: do not beat her. But at the end of three years, if she still continues ignorant, then beat her, but do not take her life; for if you do, I shall demand the price of blood at your hands, but for beating her I shall not hold you responsible or interfere. '

"All marriages, however, do not go on in this happy fashion: it often happens that the lad and the lass have made up their minds to couple, but the parents will not hear of the match. In such a case the lovers generally elope together; but should the girl's parents be very much set against the match, they have the right to demand back and take their daughter from the hands of her lover. If, notwithstanding this opposition, the lovers' intentions still remain tmaltered and they elope a second time, no one has then the right to interfere with them. The young husband makes a present to his father-in-law according to his means, gives a feast to his new relatives, and is formally admitted into kinship."

Sexual indiscretions before marriage are not severely dealt with, and usually end in marriage. But a man who carries off a young girl against her will is fined Rs. 60, and "also receives a good beating from the lads of the village to which a girl belongs." Incest is punished by a fine of Rs. 50 and corporal punishment. Once married, the chakma. women axe said to be good and faithful wives, and it is unusual for the village council to be called upon to exercise its power of granting a divorce. Such cases, however, do occur occasionally. The offender has to repay to the husband tho bride-price and the expenses incurred in the marriage, and in addition a fine of Rs. 50 or Rs. 60, which is divided between the dewan or ahUn of the sept and the Chief of the tribe. Divorced women can marry again. A widow is allowed to marry a second time. She may marry her husband's younger brother, but is not obliged to do so. the ceremony is simple, consisting mainly of a feast.

Religion

The Chakmis profess to be Buddhists, but during the last generation or so their practice in matters of Religion. religion has been noticeably coloured by contact with the gross Hinduism of Eastern Benga1. This tendency was encouraged by the example of Raja Dhann Baksh Khan and his wife Kilindi Rani, who observed the Hindu festivals, consulted Hindu astrologers, kept a Chittagong Brahman to supervise the daily worship of the goddess Kali, and persuaded themselves that they were lineal representatives of the Kshatriya caste. Some years ago, however, a celebrated Phoongyee came over from Arakan after the H.aja's death to endeavour to strengthen the cause of Buddhism and to take the Rani to task for her loadings towards idolatry. Ilia efforts aro said to have met with some success, and the Rani is believed to have formally proclaimed her adhesion to Buddhism. Lakhsmi is worshipped by the Tungjainya sub-tribe as the goddess of harvest in a small bamboo hut set apart for this purpose. She is represented by a rude block of stone with seven skeins of cotton bound seven times round it. The offerings are pigs and fowls, which are afterwards eaten by the votaries. Chakmas observe the same worship with a few differences of detail, which need not be noticed here.

Vestiges of the primitive animism, which we may believe to have been the religion of the Chakmas before their converion to Buddhism, still survive in the festival called Shongbasa, when nats, or the spirits of wood and stream, are worshipped, either by the votary himself 01' by an exorcist (ojha or naichhura), who is called in to perform the necessary cercmonies. The demons of cholera, fever, and other diseases are propitiated in a river-bed or in the thick jungle, where spirits delight to dwell, with offerings of goats, fowls, ducks, pigeons, and flowers. The regular priests have nothing to do with this ritual, which has been condemned as unorthodox.

"At a Chakma village," says Major Lewin, "I was present when sacrifice was thus offered up by the headman. The occasion was a thank-offering for the recovery of his wife from child-birth. The offering consisted of a suckling pig and a fowl. the altar was of bamboo, decorated with young plantain shoots and leaves. On this raised platform were placed small cups containing rice, vegetables, and a spirit distilled from rice. Round the whole from the house-mother's distaff had been spun a long white thread, which encircled the altar, and then, carried into the house, was held at its two ends by tho good man's wife. The sacrifice commenced by a long invocation uttered by the husband, who stood opposite to his altar, and between each snatch of his charm he tapped the small platform with his hill knife and uttered a long wailing cry. This was for tho purpose of attracting the numerous wandering spirits who go up and down upon the earth and calling them to the feast. 'Whcn a sufficient number of these invisible guests were believed to be assembled, he cut the throats of the victims with his dao and poured a libation of blood upon the altar and over the thread. The flesh of the things sacrificed was afterwards cooked and eaten at the household meal, of which I was invited to partake."

Of late years Bainigi Vaishnavas have taken to visiting the Ilill Tracts, and have made a few disciples among the Chakmas. The outward signs of conversion to Vaishnavism are wearing a necklace of tulsi beads (Ocymum sanctum), which is used to repeat the mantra or mystic formula of the sect. Abstinence from animal food and strong drink is also enjoined. I understand, however, that very few Chakmas have been found to submit to this degree of austerity.

Funeral

Chakmas burn their dead. The body of a man is burned with the bead to tho west on n. pyre composed of Five layers of woman on a wood ;that of a women on a pyre of seven layers, the head being turned to the east. The ashes are thrown into the river. A bamboo post, or some other portion of a dead man's house, is usually burned with him-prob¬ably in order to provide him with shelter in the next world. At the burning plaoe the relatives set up a pole with a streamer of coarse cloth. Infants and persons who die of small-pox or cholera or by a violent death are buried. If a man is supposed to have died from witch craft, his body when half-burned is split in two down the chest-a practice curiously analogous to the ancient treatment of suicides in Europe. Seven days after death priests are sent for to read prayers. for the dead, and the relatives give alms. It is optional to repeat this ceremony at the end of a month. At the end of the year, or at the festival of navanna (eating of new rice), rice cooked with various kinds of curry, meat, honey, wine, are offered to departed ancestors in a separate room and afterwards thrown into a river. Should a flea, or, better still, a number of fleas, be attracted by the repast, this is looked upon as a sign that the dead are pleased with the offerings laid before them.

Occupation

Like the rest of the Hill Tribes, the Chakmas live by Jhum cultivation, which they carry on in the method described below in the article Magh. In spite of the necessarily shifting character of their husbandry, they show remarkable attachment to the sites of their villages, and do not change these like most of the other tribes. Theil' bamboo houses, built upon high piles, are constructed with great oare. An excellent sketch of one of these is given by Dr. Riebeok in the book already referred to. The Census statistics of the Chakma tribe show an extraordinary fluctuation in their numbers, which I am wholly unable to account for. In 1872 there were 28,097 chakmas in the Chittagong will Tracts, while the Census of 1881 shows only eleven! No attempt is made to clear up this singular ViilkenoctncZel'ung in the text of the Census Report of 1881.

Citizenship

Granted Indian citizenship: 2017

Chakma and Hajong refugees - India's new citizens, Sep 18, 2017: The Times of India

Who are Chakmas and Hajongs?

The Chakmas and Hajongs are ethnic people who lived in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, most of which are located in Bangladesh. Chakmas are predominantly Buddhists, while Hajongs are Hindus. They are found in northeast India, West Bengal, Bangladesh, and Myanmar.

If they are indigenous people, why are they called refugees?

The Chakmas and Hajongs living in India are Indian citizens. Some of them, mostly from Mizoram, live in relief camps in southern Tripura due to tribal conflict with Mizos. These Indian Chakmas living in Tripura take part in Mizoram elections too. The Election Commission sets up polling booths in relief camps.

The Chakmas and Hajongs living in the Chittagong Hill Tracts fled erstwhile East Pakistan in 1964-65, since they lost their land to the development of the Kaptai Dam on the Karnaphuli River. In addition, they also faced religious persecution as they were non-Muslims and did not speak Bengali. They eventually sought asylum in India. The Indian government set up relief camps in Arunachal Pradesh and a majority of them continue to live there even after five decades. According to the 2011 census, 47,471 Chakmas live in Arunachal Pradesh alone.

Why does Arunachal Pradeshhave a problem with Chakmas?

In the 1960s, the Chakma refugees were accommodated in the relief camps constructed in the "vacant lands" of Tirap, Lohit and Subansiri districts of the erstwhile North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), a political division governed by the Union government. In 1972, NEFA was renamed Arunachal Pradesh and made a Union Territory, and subsequently, it attained statehood. The locals and regional political parties opposed re-settling refugees in their land fearing that it may change the demography of the State and that they may have to share the limited resources available for them.

What about Bangladesh?

The Chakmas and Hijongs opposed their inclusion in undivided Pakistan during Partition. They later opposed their inclusion in Bangladesh when East Pakistan was fighting the Liberation War with West Pakistan, on grounds that they are an ethnic and religious minority group. A group of Chakmas resorted to armed conflict with Bangladeshi forces under the name 'Shanti Bahini'. The conflict increased the inflow of refugees to India.

In 1997, the Bangladeshi government headed by Sheik Hasina signed a peace accord with the Shanti Bahini, which resulted in the end of the insurgency. According to the accord, the Chakma, Marma, Tripura, Murang and Tanchangya were acknowledged as tribes of Bangladesh entitled for benefits and a Regional Council was set up to govern the Hill Tracts. The agreement also laid out plans for the return of land to displaced natives and an elaborate land survey to be held in the Hill Tracts.

Bangladesh was willing to take back a section of Chakma refugees living in India, but most of them were unwilling, fearing the return of religious persecution.

HIGHLIGHTS

The move to grant the Chakma and Hajong refugees citizenship is facing opposition in the refugees' main home state of Arunachal Pradesh, on claims that the move will change the demographics of the mostly tribal state. A look at the refugees and their struggle…

Origins

Chakmas and Hajongs came to India from the Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan), having lost their homes and land to the Kaptai dam project (Karnaphuli river) mid-1960s. They also faced religious persecution

Religion: Chakmas are Buddhists, while Hajongs are Hindus

Language: Chakmas' is close to Bengali-Assamese; Hajongs speak a Tibeto-Burman tongue written in Assamese Where they settled

Who stayed on...

- An estimated 1 lakh Chakma and Hajong refugees are staying in India

- When they came in 1964, there were about 15,000 Chakmas and about 2,000 Hajongs

- By 2015, many of the initial group of refugees had died. Only about 5,000 were in the camps

- In 2010-11, a survey by MHA placed their in Arunachal's three districts at 53,730

- In 1987, a new group of 45,000 Chakmas crossed over to Tripura from Bangladesh

...having called India home

- To date, Chakmas observe a 'Chakma Black Day', condemning the award of Chittagong Hill Tracts to then east Pakistan in 1947

- Neither did they want to be part of Bangladesh when it was formed in 1971 and launched an armed struggle Shanti Bahini for autonomy

- Fighting the Bangla Army routinely saw Chakmas move into India, moving to Tripura

- In 1990s, Sheikh Hasina's govt struck a peace deal with the Chakmas, recognizing them as a Bangla tribe

- But the Chakmas did not return, fearing persecution

Can they vote?

In 2005, Election Commission issued guidelines to include Chakmas and Hajongs in Arunachal's electoral rolls. Names of over 1,000 Chakmas appear in Arunachal's electoral rolls

A timeline of their battle in court

Early 1990s: Committee of Citizenship Rights for the Chakmas of Arunachal Pradesh (CCRCAP) formed to fight for citizenship rights

Dec 1994: National Human Rights Commission asks Arunachal government and Centre to provide information about steps taken to protect Chakmas and Hajongs

1995: In face of a deadline set by local tribes for Chakmas, Hajongs to leave the state, NHRC moves SC seeking relief for the refugees

Nov 2, 1995: In interim order, SC directs state government to "ensure that the Chakmas situated in its territory are not ousted by any coercive action, not in accordance with law"

Jan 9, 1996: SC directs govt to expedite their citizenship applications

Sept 2015: SC gives deadline to the Centre to confer citizenship to these refugees within three months

Sept 2017: Home ministry announces citizenship to be given

Why grant citizenship now?

In 2015, the Supreme Court directed the Centre to grant citizenship to Chakma and Hajongs who had migrated from Bangladesh in 1964-69. The order was passed while hearing a plea by the Committee for Citizenship Rights of the Chakmas. Following this, the Centre introduced amendments to the Citizenship Act, 1955. The Bill is yet to be passed, as the opposition says the Bill makes illegal migrants eligible for citizenship on the basis of religion, which is a violation of Article 14 of the Constitution.

The Union government is keen in implementing the Supreme Court directive now since the BJP is the ruling party in both the Centre and Arunachal Pradesh.

The Union Home Ministry cleared the citizenship for over one lakh Chakma-Hajongs. However, they will not have any land ownership rights in Arunachal Pradesh and will have to apply for Inner Line Permits to reside in the State.

Though cleared for citizenship now, they can't own land in Arunachal and will have to apply for Inner Line Permits