Chandal, Chanral

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

Contents |

Chamdal, Chanral

Traditional of Origin

Chang, Nama-Sudra, Nama, Nishad, a non-Aryan caste of Eastern Bengal, engaged for the most part in boating and cultivation. The derivation or the name Chandal is ' uncertain, and it is a plausible conjecture that it may have been, like Sudra, the tribal name or one or the aboriginal races whom the A.Tyans found ill possession of the soil. Un like the Sudras, however, the chandals were debarred from entering even the outer circles or the Aryaun system, and from the earliest times they are depicted by Sanskrit writers as an outcast and helot people, performing menial duties for the Brahmans, and living on the outskirts of cities ' (antebasi) apart from the dwellings of the dominant race. Iron ornaments,

1 The following synonyms are given by Amara Sinha :-Plava (the wanderer), Matanga (elephant), Jannmaghana (life-taker), Svapacha (dog-oater), Antevasi (the dweller on the confines of the village), Divakirtti, and Pukkasa. None of those are in common use at the present day. 2 Chang or Changa, says Dr. Wise, significs handsome in Sanskrit, " and was most likely used in irony by the early Hindus." . 3 The derivation of this name is uncertain. Dr. Wise thinks it may be from H the Sanskrit Narnas, adoration, which is always used as a vocative when praying, or the Bengali Namate, below, underneath." The latter suggestion seems the more plausible. The Pundits' interpretation of the former is understood to be that the Chandal is 'found to do obeisance even to a Sudra. It would be promotion for the Chandals of Manu to get themselves recognised as a lower grade of Sudras. The name may also be referred to Namasa or Lomasa Muni, whom some Chadals regard as their mythical ancestor. On the other hand, Namasa Muni himself may have been evolved from the attempt to explain away the suggestion of inferiority implied in the nume Nama-Sudra. dogs, and monkeys, are their chief wealth, and they clothe themselves in the raiment of the dead. Manu brands them as "the lowest of mankind," sprung from the illicit intercourse of a Sudra man with a Brahman woman, whose touch defiles the pure and who have no ancestral rites. In the Mahabharata they are introduced as hired assassins, whose humanity, however, revolts against putting an innocent boy to death. In the Ramayana they are described as in-formed and terrible in aspect, dressing in blue or yellow garments with a red cloth over the shoulders, a bear's skin around the loins, and iron ornaments on the wrists. Even the liberal-minded Abul Fazl speaks of the Chandals of the sixteenth century as "vile wretches who eat carrion." At the present day the term ChandaI is through¬ out India used only in abuse, and is not acknowledged by any race or caste as its peculiar designation . The Chandals of Bengal invariably call themselves Nama-Sudra, and with characteristic jealousy tho higher divisions of the caste apply the name Chandal to the lower, who in their turn pass it on to the Dom.

The legends of the Chandals give no clue to their early history, and appear to have been invented in recent times with the object of glorifying the caste and establishing its claim to a recognised position in the Hindu. system. Thus, according to a tradition of the Dacca Chandals, they were formerly Brahmans, who became degraded by eating with Slidras, while others assert that in days of yore they were the domestic servants of Brahmans, for which reason they have perpetuated many of the religious observances of their masters. For instance, the Chandal celebrates tho Sraddha on the eleventh day as Brahmans do, and the Gayawal priests conduct the obsequial ceremonies of the Bengali Chandals without any compunction. Another story gives them for ancestor Bamdeb, son or the Brahman Vasishtha, who was degraded by his father and turned into a Chandal as punishment for a ceremonial mistake committed by him when granting absolution to Dasaratb, King of Oudh, for killing a Brahman by misadventure while hunting.

The Dacca Chandals retain an obscure tradition of having originally migrated from Gaya, and mako mention of a certain Govardhan Chandal as an ancestor of theu"s. Mr. Wellsl quotes a tradition of Hindu invention, current among the ChandAls of Faridpur, to the e:fIect "that they were originally a complete IIindu community, consisting of persons of all castes, from the Brahman down wards, who, on baving the misIortune to be cursed in a body by a vengeful Brahman of unutterable sanctity in Dacca, quitted theu" ancestral homes and emigrated bodily to the southern wastes of Faridpur, J essore, and Baqirganj ."

Dr. Buchanan considered tho Chandal of Bengal to be identical with the Dosadh of Behar. Although hoth are equally low in the scale of caste, and characterised by an unusual amount of independ¬ence and self-reliance, very great differences actually exist. The Dosadh worships deified heroos belonging to his tribe; the Chandal never does. The Dosadh invokcs Rahu and Ketu, the former being his tutelary deity, while we find no such divinity reverenced by the Chandal. Finally, the sraddha of the Do idh is celebrated on the thirtieth day, as with the Sudras; that of the Chandal on the eleventh, as with Brahmans.

Mr. Beverley, again, is of opinion that Chandal is merely a generic title, and the tribe identical with the Mals of the Rajmahal Hills, an undoubted Dravidian clan, and demonstrates from the Census figures that in many districts the number of Chandals is in the inverse ratio to the Mals. There appear to be some grounds for this supposition, but an obvious error occurs in the return of 4,663 Mals in Dacca, where none exist, and the omission of any Malos, who are numerous. The latter, though undoubtedly a remnant of some aboriginal race, have not as yet been identified with the Mals.

It may perhaps be inferred from the prespnt geographical posi-tion of the Chandals that they came into contact with the Aryans at a comparatively late period, when the caste system had already beeu fully developed and alien races were regarded with peculiar detestation. This would account in some measure for the curious violence of the condemnation passed on a tribe iu no way conspicu¬ous for qualities calcul ated to arouse the feeling of physical repul¬Aion with which the early writers appear to regard the Chandals. It is possible, again, that they may have offered a specially stubborn resistance to the Aryan advance. Dr. 'Wise refers to the facts that they alone among the population of Lower Bengal use the Kayathi Nagari, the common written language of Dinajptlr, and that a Chandal Raja ruled from the fort, whose ruins are still shown in the Bhowal jungle, to prove that they were in early times a strongly-organized commonwenlth driven forth from their homes in the nO'rth in search of freedom and security of religious worship.

Internal structure

The internal structure of the caste is shown at length in Appendix 1. It will be observed that only four exogamous groups are known, and that the main body of ChandHs in Eastern Bengal have only one section, Kasyapa, Which i necessarily inoperative for the purpose of regulating marriage. In Bardwan the mythical ancestor Lomasa or Namasa, referred to in the note on page 183, appears as a section, but here, again, the system is incomplete. In two sections they are said to be recognised, but which have clearly been borrowed from tho Brahmanical system with the object of exalting the social standing of the caste. Titles, on the other hand, are very numerous, and in differeut parts of the country a host of sub-castes have been formed, having reference for the most part to real or supposed differences of occupation. Thus, according to Dr. Wise, the Chandals of Eastern Bengal have separated into the following eight classes, the members of which never eat, and seldom intermarry, with each other :¬

(1) Hid wah, from hat, 'a plough,' are cultivators; C.6) Ghasi are grass-cutters; (3) Kandho, from skandha, 'the shoulder,' are palanquin-bearers; (4) Karral are fishmongers; (5) Bari, probably a corruption of bar/uii, are carpeuters j (6) Berua, from byada ber, ' an inclosure,' fishermen ; (7) Pod i (8) Baqqal, traders and hucksters. The Halwah claim precedence over all the others, Dot only as being of purer descent, but as preserving the old tribal customs unchanged. They associate with and marry into Rami! families, but repel the other classes. The Pod, numerous in Hughli and J essore, but unknown in Dacca, are cultivators, potters, and fishermen, and are also employed as club-men (ldthiyals) in squabbles about landed property.

The question naturally arises whether some at any rate of these groups are not really independent ca tes whose members would 1l0W disown all connexion with the Chandals. The POds, for example, at any rate in the 24-Parganas, affect to be a separate caste, and would probably resent the suggestion that they were merely a variety of Chandals. Tbis faot, however, does not neoessarily affeot the aoouraoy of Dr. Wise's observations, whioh were made nearly twenty years ago, in the district of Daooa. The subdivisions of the lower castes are always on thelook-outfor chances of promoting themselves, and the claims set up by the Pods in the 24-Parganas are quite compatible with the theory that they were originally an offshoot from the ChandHs further east. The tendenoy towards separation is usually strongest among groups whioh have settled at a distanoe from the parent caste.

In Central and Western Bengal the sub-castes appear to have reference solely to oooupation. Thus in Murshedabad we find the Helo or Haliya Chandals confining themselves to agriculture, and the Jelo or Jaliya making their livelihood as fishermen. The Nolo group make mats and work in reeds (nat), and the Kesar-Kalo manufaoture reed-pens. Of the Hughli sub-castes, the Saro are agrioulturists, the Siuli extraot the juioe of date and palm-trees, the Kotal serve as chaukiddars and darwans, while the Nunia deal in vegetables and fish. The name of the Saralya sub-caste of Noakbali suggests a possible connexion with the Saro of Hughli, but the former are fishermen, sellers of betel-nut, and palanquin bearers, while the latter deem any occupation but agriculture degrading. The Amarabadi are also fishermen, but do not carry palanquins. The Bachhari are cultivators, who deal also in hogla leaves and mats. The Sandwipa appero: to be a looal group, who live in the island of Sandip and grow betel for sale. A man or woman of a higher caste living with and marrying a Ohandal may be taken into the caste by going through certain ceremonies and feeding the caste men.

Marriage

chandals marry their daughters as infants and observe the same ceremony as most of the higher castes: in this, as in other matters, the tendency to arrogate sooial importance may be observed. Dr. Wise remarks that " the chandalni bride, who in old days walked, is now carried in state in a palanquin," from which it may perhaps be inferred that infant-marriage has been introduced in comparatively recent times in imitation of the usages of the upper classes of Ilindus. In the case of the Chanda.ls it is not due to hypergamy, for no hypergamolls groups have been formed, and the ancient custom of demanding a bride-price bas not yet given place to the bridegroom-price insisLed on by the higher castes. In Western Bengal, indeed, there would seem to be some scarcity of women, for the usual bride-price is !rom Rs. 100 to Rs. 150, and as much as Rs. 250 is sometimes paid. A similar infArence may perhaps be drawn from a statement made to me by a good observer in Eastern Bengal, that marriages are usually celebrated in great haste, as soon as possible after the contract has been entered into by the parents. the rice harvest, when people meet daily in the fields, is the great time for discussing such matters; and the month of Phalgun, when agricultural work is slack, is set apart for the celebration of marriages. Polygamy is permitted in theory, but the extent to which it is practised depends on the means of the individuals concerned. Widow-marriage, once universally practised, has within the last generation been prohibited. Divorce is under no circumstances allowed.

Birth customs

After the birth of a male child the ChandaI mother is cere monially unclean for ten days, but for a female child the period varies from seven to nine days. Should the child die within eighteen months, a sraddha is observed after three nights; but should it live longer, the obsequial ceremony is held at the expiration of ten days. On the sixth day after the birth of a boy the Sashthi Pllja is performed, but omitted if the child be a girl. Whenever a Chamain, or Ghulam Kayasth female, is not at hand, the Chandalni acts as midwife, but she never takes to this occupation as a means of livelihood.

Religion

Although the majority of the caste profess the tenets of the Vaishnava sect of Hindus, they still retain many peculiar religious customs, survivals of an earlier animistic cult. At the Bastu Puja on the Paus Sankrant, when the earth goddess is worshipped, the Chandals celebrate an immemorial rite, at which the caste Brahman does not officiate. They pound rice, work it up into a thin paste, and, colouring it red or yellow, dip 11 reversed cup into the mess, and stamp circular marks with it on the ground in front of their houses and on the flanks of the village cattle. This observance. which, according to Dr. Wise, is not practised by any other caste, has for its object the preservation of the village and its l)prperty nom the enmity of malignant spirits. In Central Bengal a river god called Bansura is peculiar to the fishing sub-castes of Chandals. His function is supposed to be to protect fish from evil spirits who are on the watch to destroy them, and if he is not propitiated by the blood of goats and offerings of rice, sweetmeats, fruit and flowers, the popular belief is that the fishing season will be a bad one. " Throughout Bengal," says Dr. Wise, "the month of Sravan (July-August) is sacred to the goddess of serpents, Manasa DevI, and on the thirtieth day the Chandals in Eastern Bengal celebrate the Nao-Ka-Puja, literally boat worship, or, as it is more generally called, Chandals .Kudni, the Chandals' rejoicing. As its name imports, the occasion is a very festive one, in Silhet being observed as the great holiday of the year. The gods and goddesses of the Hindu mythology are paraded, but the queen of the day is the great snake goddess, Manasa Devi A kid, milk, plantains, and sweetmeats are offered to her, and the day is wound up with processions of boats, boat races, feasting and chinking. On the Dacca river the sight is singularly interesting. Boats manned by twenty or more men, and decked out with triangular £lags, are paddled by short rapid strokes to the sound of a monotonous chant, and as the goal is neared, loud cries and yells excite the contending crews to fresh exertions. (the Kuti Mahomedans compete with the Chandals for prizes contributed by wealthy H indu gentlemen."

Occupation

Although subdivided according to trades, Chandals actually work at anything. They are the only Hindus employed in the boats (bajra) hired by Europeans ; they form a large proportion of the peasantry; and they are shopkeepers. goldsmiths, blacksmiths, carpenter, oilmen, as well as successful traders. They are, however, debarred from becoming fishermen, although Sslling for domestic use is sanctioned. In Northern Bengal they catch fish for sale.

Social Status

Chandals have Brahmans of their own, who pre ide at religious and social ceremonies; but they are popularly called Barna-Brahman or Chandiiler Brahman, and in Eastern Bengal are not received on equal terms by other members of the priestly caste. Their washermen and barbers are of necessity Chandals, as the ordinary Dhoba. and Napit decline to serve them. In Western Bengal, on the other hand, Chanda'l have their clothes washed by the Dhoba, who works for other castes. The BhUinmali also is reluctant to work for them, and there is much secret jealousy between the castes, which in some places has broken out into open feuds. At village festivals the Chandal is treated as no higher in rank than the BhliinmaH and Chamar, and is obliged to put off his shoes before he sits down in the assembly. Although he has adopted many Hindu ideas, the Chandal still retains his partiality for spirits and swiue's flesh. In the Pirozpur thana of Bakarganj the Chandals have recently started a combined movement to call themselves Namas, to wear shoes, and not to take rice from Kayasths or Sudras. This departure from the customs of their ancestors was vehemently disapproved of by tho Mahomedan zamindars of the neighbourhood, and a breach of the peace was considered imminent. The clean Sudra castes occasionally, and the unclean tribes always, sit with the chandal, and at times will accept his dry pipe. Nevertheless, vile as he is according to IIindu notions, the Chandal holds himself polluted if he touches the stool on which a Sunri is sitting.

Chandals are very particular as regards caste prejudices. They never allow a European to stand or walk over their cooking place on board a boat, and if anyone inadvertently does so while the food is being prepared, it is at once thrown away. They are also very scrupulous about bathing before meals, and about the cleanliness of their pots and pans. Still more, they take a pride in their boat, and the tidy state in which they keep it contrasts forcibly with the appearance of one manned by Mahomedan boatmen. On the whole, Dr. Wise regards the Chandal as "one of the most lovable of Bengalis. He is a merry, careless fellow, very patient amd hard-working, but always ready, whon his work is done, to enjoy himself.Chnandls are genern.lly of very dark oomplexion, nearer black than brown, of short musoular figures and deep, expanded chests. Few ,are handsome, but their dark sparkling eyes and merry laugh make ample amends for their generally plain features. In the 24-Parganas many members of the caste are said to be of a not:ceably fair complexion . Singing is a favourite amusement, and a Chandal crew is rarely without some musical instrument with which to enliven the evening after the toils of the day. When young, the Chandal is very vain of his personal appearance, always wearing his hair long, and when in holiday attire combing, oiling, and arranging it in the most winsome fashion known. Many individuals among them are tall and muscular, famed as clubmen and watchmen. During the anarchy that accompanied the downfall of Moghal power, the rivers of Bengal swarmed with river thugs or dakaits, who made travelling unsafe and inland trade impossible. The Chandals furnished the majority of these miscreants, but since their dispersion the chandal has become a peaceful and exemplary subject of the Eng-lish Government."

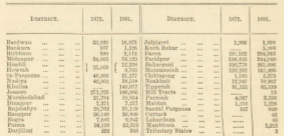

The following statement shows the Dumber and distribution of chandcUs in 1872 and 1881. The figures tor Kotal are included in the column of 1872 and excluded n:om that of 11:\81.