Chero, Cheru

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

Contents |

Chero, Cheru

Origin

A landholding and cultivating caste of Behar and Chota Nagpur. Found also in Benares and Mirzapur. Sir Henry Elliot, while mentioning the opinions that the Cheros are a branch of the Bhars or are con-nected with the Kols, appears himself to have considered them to be the aboriginal inhabitants of the provinces on the skirts of which they are now found, driven from their proper seats by Rajput races. It was Colonel Dalton's opinion that the Gangetic provinces were once occupied by peoples speaking a Rolarian language closely allied to the present Munda dialect, among whom the Cheros were the latest dominant race. If, however, the chel'oS and Kols originally formed one nation, the Kols must have parted from the parent stock and settled in Chota Nagpur before the former tribe embraced Hinduism and erected the various temples of which the ruins are still referred by local tradition to their rule in Behar; for all of these are dedicated to the worship of idols, and it is a distinctive feature in the Religion of the Kols of the present day, as 01 most races in the animistic stage of belief, that they never attempt to represent their deities or to build any sort of habitation for them. Convincing proof of the non-Aryan affinities of the CheloS is derived from the fact that the Chota Nagpur members of the caste, whose poverty and social insignificance have held them aloof from Hinduising influences, still retain totemistic section-names similar to those in use among the Kharias, who are beyond doubt closely akin to the Mundas. The landholding Cheros of Palamau have borrowed the Brahmanical gotras in support of their claim to be Rajputs, and have thus successfully obliterated all trace of their true antecedents. These Cheros are divided into two sub-castes, Bara-hazar and Tera-hazar or Birbandhi. The former is the higher in rank, and includes most of the descendants of former ruling families, who assume the title Babuan. The Tera-hazar are supposed to be the illegitimate offspring of the Bara-hazar. Some of the wealthier members of the latter group who have married into local lajput houses call themselves Chohan-bansi RajpntB, and decline alliances with the Bara-hazar Cheros. For the most part, however, the Chel'oS of Palamau are looked down upon by the Cheroa of Bhojpur by reason of their engaging in the degrading occupations of rearing tasar cocoons and collecting catechu and lac. Colonel Dalton has the following remarks on the physical characteristics of the Cheros and their traditions of origin :¬

"The distinctive physical traits of the Cheros have been considerably softened by the alliances with pill'S Hindu families, which their ancient power and large possessions enabled them to secure; but they appear to me still to exhibit an unmistakable Mongolian I physiognomy. They vary in colour, but are usually of a light brown. They have, as a rule, high cheek-bones, small eyes obliquely set, and

It has been shown in the Introductory essay that the theory of the Mongol!an orlgm of the Kols and cognate tribes is untenable, and that the distinction between Kolal'ian and Dravidian rests purely on linguistic grounds. In descnbmg the Chero features as 'Mongolian,' Colonel Dalton meant that they resembled the ordinary Rol type. eyebrows to conespond, low broad noses, and large mouths with protuberant lips. It appears from Buchanan that the old cheros, like the dominant Kolarian family of Chota Nagpur, claimed to be N agbansis, and had the same tradition regarding their origin from the great' Nag,' or dragon, that has been adopted by the Chota Nagpur family. The latter were it seems, even in Gorakhpur and Behar, allowed to be the heads of the Nagbansi family, and Buchanan considered them to be cheros; but they are, no doubt, originally of the same race as their Kol subjects, though frequent alliances with Rajput families have obliterated the aboriginal lineaments. The western part of Kosala, that is, Gorakhpur, continued some time under the cheros after other portions of that territory had fallen into the hands of the people called Gurkha,Who were in their turn expelled by the Tharus, also from the north. In Shahabad, also, the most numerous of the ancient monuments are ascribed to the cheros, and it is traditionally asserted that the whole country belonged to them in sovereignty. Buchanan suggests they were princes of the Sunaka family, who flourished in the time of Gautama, about the sixth or seventh century before the christian era. An inscription at Buddh Gya mentions one Phudi Ohandra, who is traditionally said to have been a Ohero. The Cheros were expelled from Shababad, some say, by the Savars or Suars, some say by a tribe called Hariha. The date of their expulsion is conjectured to have been between the fifth and sixth centuries of the Christian era. Both Oheros and Savars were considered by the Brahmans of Shahabad as impure or Mlechhas, but the Harihas are reputed good Kshatriyas.

" The overthrow of the Oheros in Mithila and Magadha seems to have been complete. Once lords of the Gangetic provinces, they are now found in Shahabad and other Behar districts only holding the meanest offices or concealing themselves in the woods skirting the hills occupied by their cousins, the Kharwars; but in Palamau they retained till a recent period the position they had lost elsewhere. A Chero family maintained almost an independent rule in that pa1gana till the accession of the British Government j they even attempted to ho1d their castles and strong places against that power, but were speedily subjugated, forced to pay revenue and submit to the laws. 'They were, however, allowed to retain their estates j and though the rights of the last Raja of the race were purchased by Government in 1813, in consequence of his falling into arrears, the collateral branches of the family have extensive estates in Palamau still, According to their own traditions (they have no trustworthy annals) they have not been many generations in the pargana, They invaded that country from Rohtas, and with the aid of Rajput Chiefs, the ancestors of the 'l'bakurais or Ranka and Chainpur drove out and supplanted a Rajput Raja oi the Raksel family, who retreated into Sarguja and established himself there. It is said that the Palamau population then consisted or Kharwars, Gonds, Mars, Korwas, Parheyas, and Nageswars. Or these, the Kharwars were the people of most consideration; the cheros conciliated them, and allowed them to remain in peaceful possession of the hill tracts bordering on Sarguja. All the cheros of note who assisted in the expedition obtained military service grants of land, which they still retain. It is popularly asserted that at the commencement of the Chero rule in Palamau they numbered twelve thousand families, and the Kharwars eighteen thousand; and if an individual of one or the other is asked to what tribe he belongs, he will say, not that he is a Chero or a Kharwar, but that he belongs to the twelve thousand or to the eighteen thousand, as the case may be. The Palamau Cheros now live striotly as Rajputs, and wear the paita or caste thread. They do not, however, intermarry with really good Rajput families. I do not think they cling to this method of elevating themselves in the social soale so tenaciously as do the Kharwars. But intermarriages between Chero and Kharwar families have taken place. A relative of the Palamau Raja married a sister of ManincHh Sing, Raja of Ramgarh, and this is amongst them elves an admission of identity of origin. As both claimed to be Rajputs, they could not intermarry till it was proved to the satisfaction of the family priests that the parties belonged to the same class. But the Palamau Cheros, and I suppose all Cheros, claim to be descendants of Chain M uni, one of the Hishis, a monk of Kumaon. Some say the Rishi took to wife the daughter of a Raja, and that the Cheros are the offspring of their union; others, that the Cheros are sprung in a mysterious manner from the dshan, or seat of Chain Muni. They have also a tradition that they came from the Morang. '

Marriage

Cheros profess to marry their daughters as infants, but it seems , doubtful whether this practice has yet become Marriage. fully established among them. ']'he poorer members of the caste, particularly the totemistic Cheros of ChotaNagpur, have not yet completely out themselves loose from the non-Aryan custom of adult-marriage; while the landholding cheros find the same difficulties in getting husbands for their daughters which hamper all pseudo-Rajput families in the earlier stages of their promotion to the lower grades of the great Rajput group. The marriage service conforms on the whole to the orthodox pattern, but retains a few peculiar practices which may perhaps belong to a more ancient ritual. At the close of the bhanwar ceremony, when the couple march round an earthen vessel set up under the bridal canopy of boughs, the bridegroom, stooping, touches the toe of the bride and swears to be faithful to her through life. Again, after the binding rite of sinclu1dan has been completed, the bridegroom's elder brother washes the feet of the bride, lays the wedding jewellery in her joined hands, and then, taking the patmauri from the mattr or pith head• dress worn by the bridegroom, places it on the bride's head. The practice known as amlo also deserves notice. This is performed by the bridegroom's mother before the bridal procession (tarat) starts for the bride's house, and by the bride's mother after the procession has arrived. It consists of putting a mango leaf into the mouth and then bursting out into tears and loud lamentation: the maternal uncle of the bride or bridegroom meanwhile pours water on the leaf.

Polygamy is permitted, but is not very common. There is said to be no theoretical limit to the number of wives a man may have. Widows may many again, and among the less Hinduised members of the caste they usually do so. ,Vidow-marriage, however, is regarded with disfavour by the wealthier Cheros, who affect orthodoxy, and within a generation or so we may expect that the practice will be abandoned. Where it is still recognised, the widow is expected, on grounds of family convenience, to marry her late husband's younger brother or cousin. Sbe may, however, marry anyone else provided that she does not infringe tllfl prohibited degrees which were binding on her before her marriage, and does not select a man whose sister could not have been taken in marriage by her late husband. Divorce is not allowed. A woman found in adultery is turned out of the caste, and can under no circumstances marry again.

Religion

The Religion of the Oheros is still in a state of transition, and Kanaujia or Sakadwipi Brahmans, who are received on terms of equality by other members of the sacred order. Their spirit.ual guides (gurus) are either Brahmans or Gharbiri Gosains. They also reverence animistic deities of the type known to the Kharias and Mundas-Baghaut, Chenri, Darha, Dharti, Dukhnahi, Dwar¬par, and others, to whom goats, fowls, sweetmeats, and wine are offered in the month of Aghan so as to seoure a good harvest. In these sacrifies Brahmans take no part, and they are conducted by a priest (baigd) belonging to one of the aboriginal raoes. cheros also, like the Kols, observe triennial sacrifices. "Every three years," says colonel Dalton, "a buffalo and other animals are offered in the sacred grove of sama, or on a rook near the village. they also have, like some of the Kols, a priest for eaoh village, called palin. TIe is always one of the impure tribes, a Bhuiya, or Kharwar, or a Parheya, and is also called baiga. He alone can offer this great sacrifice. No Brahmanical priests are allowed on these occasions to interfere. The deity honomed is the tutelary god of the village, sometimes called Dual' Pahar, sometimes Dharti, sometimes Purgahaili, or Daknai, a female, or Dura, a sylvan god-the same perhaps as the Darha of the Kols. I found that the above were all worshipped in the village of Munka, in Palamau, which belongs to a typical chero, Kunwar Bhikari Sinh."

Social status

The Cheros of Palamau affect the ceremonial pnrity characteristic of the higher castes of Hindus, and the con naxian of their leading families with the land secures to them a fairly high social position. Many of them wear the sacred thread with which they are invested by a Brahman at the time of their marriage. Brahmans will take water from their hands, and eat anything but rice that has been cooked by them. They are held, in faot, in much the same estimation as any of the local Rajputs. In Chota Nagpur, on the other hand, the status of the caste is by no means so high, and the Bhagtas, while admitting the Cheros to be a sub-caste of their community, decline to eat with them, and regard them as socially their inferiors. Agriculture is supposed to be the original occupation of the caste, and in Palamau many of them still hold various kinds of jagir tenures. Some have taken to shopkeeping and petty trade, while others live by cartage, working on roads or in coal-mines, and by collecting tasar cocoons, catechu, and lac. For all this, says Mr. Forbes, "the cheros are a proud race, and exceedingly jealous of their national honour. They cave never forgotten that they were once a great people, and that their descent was an honourable one. Only the very poorest among them will hold the plough, and none of them will carry earth upon their heads."l

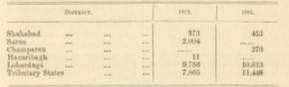

The following statement shows the number and distribution of the cheros in IH72 and 1881 :¬