Chidambaram Nataraja Temple

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Control of Temple

From: Jaya Menon & Pushpa Narayan, TNN, July 23, 2023: The Times of India

From: Jaya Menon & Pushpa Narayan, TNN, July 23, 2023: The Times of India

1885- 2014

Jaya Menon & Pushpa Narayan, TNN, July 23, 2023: The Times of India

PRAYERS AND PLEADINGS: THE MATTER IN COURT

1885: Dikshitars’ plea to have temple declared as private property nixed by Madras HC

1933: Dikshitars again denied by court when they seek exemption from rules formed under the Hindu Religious Endowment Board

1951: A law is passed that sees temple brought under government control. But on apeeal, court rules in dikshitars’ favour. Though government moves SC, it later withdraws notifications

1984: Government appoints ex- ecutive officer to run the temple under the Madras Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Act, 1959. Dikshitars move court. But the last of their petitions was dismissed in 2006

2009: Madras HC upholds appointment of executive officer, says state can intervene and regulate administration. Dikshitars’ appeal rejected

2014: Upon an appeal, SC quashes appointment of executive officer

As in 2023

Jaya Menon & Pushpa Narayan, TNN, July 23, 2023: The Times of India

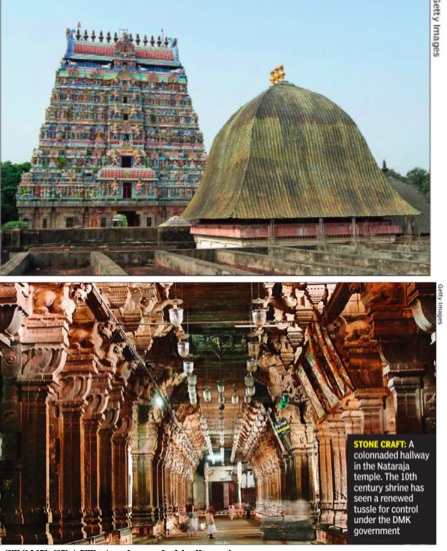

At the 10th-century Nataraja temple in Chidambaram, 230km south of Chennai, Lord Shiva’s cosmic dance – Ananda Tandavam – is frozen in an iconic metal sculpture. The temple is also believed to hold a cosmic secret, the ‘Chidambara Ragasiyam’. But, of late, the temple has been in the news for other reasons. Tussle For Control

An old tug-of-war between the Tamil Nadu government and the dikshitars (brahmin priests) over control of the temple has turned ugly since the DMK formed government in 2021. While the dikshitars cite two Supreme Court judgments from 1954 and 2014 to claim they are the temple’s legal custodians, the government says it is entitled to see the temple accounts under the Madras Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Act, 1951. Almost 50 years ago, in 1976, the state government had appointed a special tahsildar to manage the Nataraja temple’s properties that add up to 3,500 acres across Tamil Nadu. The government has been handling revenue from the land, and temple secretary T S Sivarama Dikshitar says, “Not a paisa from this comes to us”.

More recently, minister P K Sekar Babu had asked for an audit of the temple assets that include money and jewellery. The temple’s centuries-old collection of jewellery was audited for the period between January 2005 and June 2022 in July last year. But the temple custodians say they have not received a copy of the report of the latest audit, and the 2005 audit report was submitted only recently.

The government is also demanding that a ‘hundiyal’ (collection box) be kept at the temple for devotees’ offerings in cash and kind that currently go to the dikshitars. But S Rajasomashekar Dikshitar, a priest and trustee of the temple who works as an assistant professor at Annamalai University, says they can’t allow this. “Ours is the only vedic temple that does not appreciate materialistic worship since it is not mentioned in any veda,” he says.

‘Discriminatory’ Curbs

The latest flashpoint came in the last week of June when the dikshitars prevented devotees from getting onto the ‘kanagasabai medai’, an extended platform of the sanctum sanctorum during the ‘Aani Thirumanjanam’ festival. On the night of June 27, police and officials of the state Hindu Religious & Charitable Endowments (HR&CE) department got into a tussle with the dikshitars and removed a notice banning entry on the platform. In Chennai, HR&CE minister Sekar Babu announced that his government had ended a longstanding “discriminatory ban”. But the dikshitars say this restriction is not new. Every day during the ‘Aaru Kala Puja’ that lasts 25-40 minutes, one of the two lingams (Chandramouleeswarar and Ratinasababathi) placed in a box below the Nataraja statue is brought to the medai for worship. During the puja, only the dikshitars are allowed on the platform.

The same is done during three major festivals, ‘Aani Thirumanjanam’ and ‘Aarudra Darisanam’ (four days each) and Mahashiv- aratri. On these days, the ‘moolavar’ (the supreme deity) is kept on the medai before being moved to ‘rajasabai’ near the temple’s 1,000-pillar mandapam.

The medai was at the centre of a caste controversy in February 2022 when police booked 20 dikshitars under the SC/ST Act for “preventing a dalit woman from praying”. J Jayasheela, the 38-yearold woman, said when she tried to step on to the kanagasabai medai, several diskhitars shouted at her, asking her to get down. “They insulted me using my caste name. I complained to the local police,” she says. The case is pending.

Gemini M N Radhakrishnan, a Congress functionary, said he and a group of people protested when they were not allowed on the medai. “We were also not allowed to sing the ‘thevaram’ (Tamil hymns in praise of Lord Shiva) on the medai. ” The dikshitars themselves don’t agree on the medai question. Darshan Dikshitar, 33, who is facing ‘action’ by the dikshitars’ body for allegedly attacking a woman devotee, says, “While 110 dikshitars want to allow devotees on the medai, 150 others are opposed to it and the remaining 140 don’t care. ”

HR&CE joint commissioner J Bharanidharan, who was posted in Cuddalore about a month ago, says the focus is now on the medai. “Every day, an executive officer is sent to the temple to ensure devotees are permitted on the medai,” he says.

Other Controversies

The ‘Chidambara Ragasiya’ puja, which is offered to the formless nature of God behind a curtain, is also mired in controversy. The priest of the day parts the curtain and performs the puja. This is visible only from the kanakasabai medai. “Due to commercialisation, this puja has been discontinued,” says Rajasomashekar Dikshitar.

Now, the 2014 Supreme Court verdict is also a bone of contention. “The judgment says the rights of ‘denominational religious institutions’ are to be preserved and protected from any invasion by the state, as guaranteed under Article 26 of the Constitution,” says Temple Worshippers’ Society president and advocate T R Ramesh. But minister Sekar Babu counters: “Nowhere does the SC say the (Nataraja) temple is a denominational temple. ” The state should administer the temple, he insists.

Ramesh accuses the government of double standards. “The government that claims to protect minorities is out to decimate a micro-community (dikshitars) that has been in Chidambaram for 20 centuries,” he says. Many in the 1,200-member dikshitar community view the government’s interference as a battle for survival.

While fighting the government in courts – and the temple precincts – the dikshitars claim Lord Nataraja had brought them from Mount Kailash to Chidambaram and ordained them as the custodians of the temple. But the minister has a different view: “The temple is not meant for the 400 dikshitar families. It was built by the kings, not the dikshitars. ”