Childcare institutions: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Government oversight is limited

Audit, c.2018

From: Ambika Pandit, Step up registration of child shelters, Centre tells states, August 9, 2018: The Times of India

1,339 Homes Yet To Register, SC Deadline Ended On Dec 31 Last Yr

At a time when cases of sexual abuse from children homes in Muzaffarpur and Deoria have shocked the nation, it turns out that the agency appointed for pan-India mapping and audit of children’s homes as per the

directions of the Supreme Court has been denied access to childcare institutions in nine states, including Bihar and UP. This despite the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) and the ministry of women and child development writing to the states to comply with the SC’s orders.

The states where the audit agency is yet to access homes also include Delhi, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Kerala and West Bengal. Odisha, too, was on this list but the Centre’s intervention finally led to it agreeing to the audit exercise. The view emanating from these states is that they want to do their own audits.

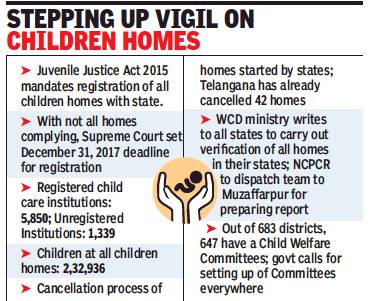

According to data available with NCPCR, there are 5,850 registered childcare institutions as on date and 1,339 homes that are yet to register though the SC had set a deadline of December 31 last year.

71 childcare institutions in Bihar, 231 in UP: NCPCR data

There may be more such institutions which are not in the NCPCR list and hence the mapping exercise under the audit is critical. In Bihar, as per NCPCR data, there are 71 childcare institutions and 231 in UP.

The NCPCR has intimated the status of the audit to the SC in a recent hearing in the ongoing public interest litigation, officials said. So far, the Lucknow-based Academy of Management Studieshas carried out the audit and mapping of 3,000 institutions across states.

According to senior NCPCR officials, the audit agency assigned the task in March conveyed to them in May that 10 states were not giving them access to their CCIs. Before that some of these states had written to the child rights body on their own expressing reservations over allowing the audit agency into these homes. NCPCR wrote back to these states and then sought the intervention of the WCD ministry to step in to resolve the impasse.

The ministry’s brass is learned to have issued an advisory in July. Meanwhile, NCPCR put forth its status report before the SC.

While Odisha had agreed to the audit exercise, NCPCR or the WCD ministry are yet to hear from the nine states on allowing the audit exercise, officials said. The NCPCR, too, has not yet heard from the audit agency if they have received any response from these nine states.

B

With over 1,300 child care institutions still out of the registration framework set out under the Juvenile Justice Act, the ministry of women and child development has stepped up action sending out letters to states asking them to verify all their homes and cancel those that fail to register. Telangana has so far cancelled 42 child care institutions and more reports are pouring into the WCD of the action taken.

Recognising that registering or cancelling homes was not enough, WCD minister Maneka Gandhi has decided to write to MPs and MLAs asking them to visit homes in their constituencies. In order to bolster monitoring mechanism, the government has also asked state commissions to fill up vacancies in Child Welfare Committees which hold magisterial powers.

Parliament was informed last week that the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) has reported that it has registered 43 complaints regarding child abuse and neglect of children in Child Care Institutions (CCIs) during the last three years up to June this year. Out of the 43 complaints, 38 have been closed and the remaining five cases are still pending.

Gandhi also feels that there was a need to consolidate the Child Care Institutions more systematically to prevent adding more and more homes and instead create more centralised facilities. She has asked the ministry to put in place a scheme in consultation with states where centralised facilities for children can be created in states and which are run only by state authorities.

Malpractices

A 2018 report

From: Piyush Tripathi, Sexual abuse rampant in 15 Bihar shelter homes: Report, August 14, 2018: The Times of India

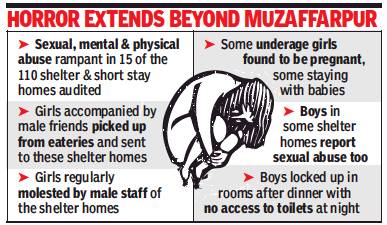

The infamous shelter home at Muzaffarpur where 34 inmates were raped is not the only one in Bihar where sexual, mental and physical abuse was rampant. Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), whose social audit report revealed the Muzaffarpur horror story and led to the arrest of kingpin Brajesh Thakur, has identified 14 other such shelter homes across the state.

Underage inmates were reported to be pregnant in some of these shelter homes “and some even had babies”.

TOI is in possession of the 100-page TISS report, which audited 110 shelter and shortstay homes across 35 districts. Sources said the government is likely to make the report public soon.

The TISS report elaborates on sexual and physical abuse in 15 centres, including the one run by Thakur, in a separate section titled “Grave Concerns — Institutions Requiring Immediate Attention”.

On Thakur’s shelter home, run by his NGO Seva Sankalp Evam Vikas Samiti, the report says: “The institution was exclusive in carrying out sexual violence on girls, all of tender age and from marginalised backgrounds, in the name of punishment and discipline. The girls said they were molested by the male staff regularly.”

Boys locked up after dinner, had no access to shelter toilets

Among the 15 notorious institutions are short stay homes run in Patna by AIKARD, Motihari (Sakhi), Kaimur (Gram Swaraj Sewa Sansthan), Madhepura (Mahila Chetna Vikas Mandal) and Munger (Novelty Welfare Society). The other shelter homes are government run Observation Home in Araria, Sewa Kutir run by Om Sai Foundation in Muzaffarpur, Kaushal Kutir run by Don Bosco Tech Society in Patna and Sewa Kutir run by Metta Buddha Trust in Gaya.

The boys’ home identified by TISS in this category are in Motihari run by Nirdesh, in Bhagalpur by Rupam Pragati Samaj Samiti, in Munger by Panaah and in Gaya run by DORD. Three specialized adoption agencies - Patna’s Nari Gunjan, Madhubani’s RVESK and Kaimur’s Gyan Bharti – are also in the “grave concerns” category.

The report highlights rampant physical and sexual harassment, corporal punishment, neglect and humiliation in “institutions of all categories”.

Elaborating on the living conditions of inmates in boys’ homes, the report says: “After dinner, the boys are locked up inside their wards and have no access to toilets throughout the night. We found plastic bottles with urine in them.”

The inmates of Muzaffarpur Sewa Kutir run by Om Sai Foundation showed bruises and broken bones to TISS members. They alleged sexual assault on them and thrashing on a daily basis by the caretakers.

The report said that many inmates lodged in short stay homes were girls who were picked up by police from eateries “while they were out with their male friends, and sent to these homes for protection”.

Life after leaving childcare institutions

48% of those who grew up in ‘homes’ lack jobs: Survey, 2019

AMBIKA.PANDIT, August 21, 2019: The Times of India

A worrisome 48% of 435 adults who grew up in child care institutions —shelters run by government and voluntary sector have shared that they were without an independent source of earning.

The information appearing in a study on the life of 18 plus adults who grew up in care institutions also shows that 93% of those who had a source of livelihood were in salaried jobs and the rest were self-employed. The average monthly salary of these adults or “care leavers” as they have been called in the study, was merely Rs 7,500-Rs 8,500. More females (63%) than males (36%) did not have an independent source of income. It is pointed out that this also reflects gender disparity and indicates that despite considerable percentage of girls completing class 12 there are fewer work opportunities for them.

The analysis is based on a study conducted in five states —Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Maharashtra. It is based on the responses of 435 adults who grew up in child care institutions and are now on their own, interviews with stakeholders and research of available literature and data. Voluntary organisation Udayan Care, Unicef and TATA Trusts have collaborated to bring out the study.

The report emphasises the fact that even though “aftercare” has been provided under the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, it has so far not been put to uniform practice, leaving children exiting CCIs, on attaining the age of 18 years, as vulnerable youth who are “no ones” responsibility.

Delhi: 2019

Ambika Pandit, August 22, 2019: The Times of India

From: Ambika Pandit, August 22, 2019: The Times of India

The existing system lacks in a big way in terms of guiding and tracking the life of children as part of the “aftercare framework” once they move out of the care homes on attaining adulthood. This was highlighted in a five-state study of 435 adults who grew up in children’s homes in Delhi, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Gujarat. The study titled “Beyond 18 Leaving Child Care Institutions” is a collaborative work of voluntary organisation Udayan Care, Unicef and Tata Trusts.

For the Delhi specific study 55 adults who grew up in children’s homes were identified and interviewed to find out where they stood in life. Delhi has two aftercare homes, one for boys in Alipur area in northwest where there are around 13 boys currently, and one for girls in Nirmal Chhaya complex in west Delhi where there are around 25 girls. Aftercare is defined as “making provision of support, financial or otherwise, to persons, who have completed the age of 18 years but have not completed the age of 21 years, and have left any institutional care to join the mainstream of the society.”

The five-state report emphasises the fact that even though “aftercare” has been provided under the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, it has so far not been put to uniform practice, leaving children exiting CCIs, on attaining the age of 18 years, as vulnerable youth who are “no ones” responsibility. Care leavers, as these adults are called, also shared their struggles at the report launch. “Will you leave your child just because he or she is 18 years old now?” 24-year-old Siddharth Yadav asked. He said that he was left to fend for himself after he attained adulthood at the child care institution. “I took refuge in a hospital complex and felt I was back on the streets I came from,” Yadav shared. Currently doing his Masters in Commerce, Yadav works as a freelance accountant.

A beneficiary of an aftercare programme implemented by the NGO run children home she grew up in, Tanu Sharma is 20 and pursuing her graduation. She feels the guidance and support she has received has helped her aim for an MBA. Sharma found herself in a children home by the circumstances created by her dysfunctional family after her mother’s death. She said that in her family girls were considered unwanted and a burden.

A software developer with an IT company 26-year-old Manoj Udayan, who grew up in a care institution and transitioned through a good aftercare experience, said, “ Most of us face challenges at every stage. The society asks us about our family and chooses to classify us as per their understanding of our circumstances. Hence support is important to overcome these emotional challenges too.” Speaking at the report launch, Aastha Saxena Khawani, joint secretary ministry of women and child development, said that during the review of the future course of the Integrated Child Protection Scheme an assessment of the aftercare system and the changes required will also be taken up. She called upon the states to implement the aftercare system and strengthen it.

Status of childcare homes

As in 2017

The crackdown on child care institutions (CCI) violating norms has resulted in 539 children homes being shut down across states, with the highest number of these being in Maharashtra. Besides irregularities, the failure of the homes to register with the state as per the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, is one of the major reasons for the ministry of women and child deciding to close these homes.

Of the 539 homes 377 are in Maharashtra, followed by 78 in Andhra Pradesh and 32 in Telangana. In Uttar Pradesh, where shocking cases from Deoria have been in the news, 20 homes have been shuttered.

The Supreme Court had set a deadline for December 31, 2017, for all unregistered CCIs to register. In an attempt to ensure compliance, the WCD ministry kept on sending repeated reminders to the states. However, after cases of abuse came to light in a home in Muzzafarpur in Bihar and then in Deoria, the WCD ministry stepped up action to crackdown on non-compliant unregistered homes.

After cases of abuse in Muzaffarpur and Deoria were unearthed, the WCD ministry had asked the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) to conduct a social audit of all the CCIs and also directed the unregistered institutes to register themselves within two months.

TOI had reported in August that over 1,300 homes — with the maximum in Kerala where the matter is in court — were still out of the registration framework. To bolster the monitoring mechanism the government has also asked state commissions to fill up vacancies in child welfare committees and set up these critical committees that hold magisterial powers.

Parliament was informed in the monsoon session that NCPCR registered 43 complaints regarding child abuse and neglect of children in CCIs over the past three years.