Chitrakoot, MP

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Fossils

The 2017 discovery

See graphic

The world’s oldest fossilised plants

Ian Johnston Science Correspondent

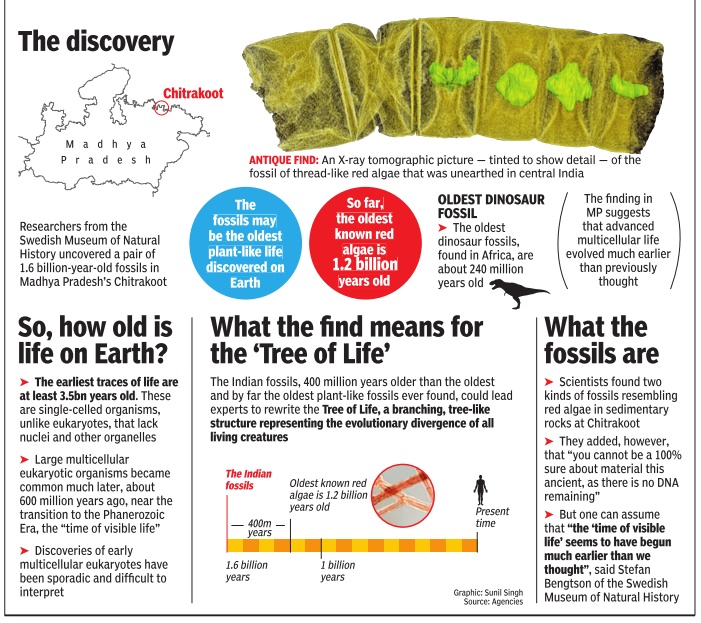

The world’s oldest fossilised plants have been found in rocks in central India, pushing back the first evolution of complex life on Earth by hundreds of millions of years.

It is a finding that suggests the so-called ‘Cambrian Explosion’ of plant and animal life about 600 million years ago may have taken much longer to develop than previously thought.

A student in Sweden made the stunning discovery while examining seemingly innocuous fossilised microbes dating from 1.6 billion years ago taken from rocks in Chitrakoot, central India.

As Therese Sallstedt looked at the samples of primitive, single-cell life through a microscope in her lab in Stockholm, she spotted something rather indistinct that seemed too advanced for the period.

But then, a few slides later, she suddenly found herself staring at a large, fleshy clump of what looked just like complex, multi-cellular red algae.

Previously the oldest accepted fossil of red algae – or any form of complex or ‘eukaryotic life’ – was from 1.2bn years ago.

But this was one of only a few known examples of complex life and it was thought that little happened before the Cambrian period.

Dr Sallstedt, who has since received her PhD, said the “million-dollar question” now was why complex life evolved but then took about a billion years to really take hold.

“Previously scientists have sometimes referred to this period of Earth’s history as the ‘boring billions’ when things are mostly microscopic and not much happens,” she told The Independent.

“The fossils we found show that complex life was there already by 1.6bn years ago, but the great radiation of animal life-forms still didn’t happen until 600m years ago.

“I guess they just waited for the right conditions. That’s like a big mystery.”

She described the moment of discovery.

“I had seen something similar a little bit before in other thin sections... but the ‘eureka moment’ was when I found this particular specimen when I saw these colonies of algae,” said Dr Sallstedt, of the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

“What I could see was the fossils were really, really big compared to the bacterial fossils surrounding them.

“They were very, very organised in this tissue-like structure in a way you don’t see in the pre-eukaryotic samples.

“That’s when I realised, wow, this must be more advanced than microbes."

Writing in the journal Plos Biology, Dr Sallstedt and colleagues at the museum and the Nordic Centre for Earth Evolution described the fossils as “exquisitely preserved... representing a shallow-water marine environment characterised by photosynthetic biomats”.

“These fossils pre-date the previously earliest accepted red algae by about 400m years, suggesting that eukaryotes may have a longer history than commonly assumed.”

Dr Sallstedt’s colleague Stefan Bengtson, professor emeritus of palaeozoology at the musem, said: “The ‘time of visible life’ seems to have begun much earlier than we thought.”

However he cautioned that, while the evidence was strong, there would always be a degree of doubt when assessing such an old fossil.

“You cannot be 100 per cent sure about material this ancient, as there is no DNA remaining, but the characteristics agree quite well with the morphology and structure of red algae,” Professor Bengtson said.

Two different types of algae, called Rafatazmia chitrakootensis, were identified, one that had a thread-like structure and another that formed fleshly colonies.

By using specialised X-ray techniques, the scientists were able to make out structures within the cells and ‘cell fountains’, bundles of splaying filaments that are characteristic of red algae.

They also believe that parts of chloroplasts – which enable photosynthesis to take place – can be seen in the fossils.

The earliest forms of life are at least 3.5bn years old, but these single-celled organisms do not have a nucleus, unlike multi-cellular algae and other complex forms of life.

Mining: A threat to historical site

The Times of India, Apr 29 2016

P Naveen

Miners have plundered idols, sculptures and remains of ancient temples dating back to the 10th and 11th century BC buried near Chitrakoot's Sarbhanga ashram, which is famous for footprints believed to be that of Lord Ram. A Madhya Pradesh archaeology department's study has highlighted the loot in the area rich in bauxite, laterite and ochre.

Sources said these items were stolen and smuggled during mining operations in last five years on the Sanwar Hill, where the ashram is located. The report said several idols were damaged due to use of heavy mining machinery . The heritage around another hillock near the ashram known as Siddha Pahar has almost vanished following rampant illegal mining. Lord Ram is believed to have spent nearly 12 years of exile at Siddha Pahar spread across 100 acres.

The Madhya Pradesh high court had in August 2015 ordered the archa eology department to study Lord Rama's route as per Ramayana (Ram Van Path) during his exile. It had asked the department to conserve sites of archaeological importance along the route within three months.

The study concluded historical importance of these sites. But the department failed to notify them as archaeo logical sites or ancient monuments.The study was ordered after the court heard a petition alleging no inquiry or study had been conducted and these sites had not been declared protected.

Petitioner Nityanand Mishra has now decided to move a contempt petition against the archaeology department. CM Shivraj Singh Chouhan had announced all routes the Lord had taken during his exile as per Ram Charit Manas would to be conserved under Ram Van Path Project in 2007. Mishra said Rs 8 crore had been spent on the project. He added a lease for carrying out mining activities just 50m from the ashram was cancelled in 2011, but it was again allowed three years later.