Cholistan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Cholistan

Sands Of Time

Text And Photographs By Sadaf Siddiqui Called the ‘land of rugged beauty’, Cholistan was described by Khwaja Ghulam Farid, the well-known mystic poet, in the following words:

“In these fair mounds and hills of sand,

These graceful stones, this gravel bland,

Ravines and tanks and gullies grand,

The rain all grief dismiss, my love”

Situated in the south of Punjab, about 30km from Bahawalpur, the desert is locally called ‘rohi’, or the land of rolling sand dunes. It extends into the Thar desert in Sindh and the Rajasthan desert in India.

Long ago Cholistan was a lush-green valley watered by the Hakra river (also known as the Ghaggar in India and as the Sarasvati in ancient Vedic times). The fertile farmland turned into arid desert when the Hakra river dried up and the population resettled near the upper course of the Ghaggar river. To date, more than 400 archaeological sites have been uncovered along the dry bed of the river.

The semi-nomads of the region wear bright clothing and speak Saraiki as well as Urdu. These people live in huts called ‘gopa’ and collect rainwater in ponds called ‘toba’ as the ground water is mostly brackish and cannot be utilised for drinking, cleaning and cooking purposes.

Encompassed by the desert on all sides is the Derawar Fort, one of the ancient forts, which was part of a trade route to India. Covering an area of about 1.5km, the fort was built by Deo Rawal, a prince from Jaiselmer in AD852.

In 1733, the fort was taken by the Abbasis from the Rajasthani royal house of Jaiselmer and presently belongs to the Nawab of Bahawalpur.

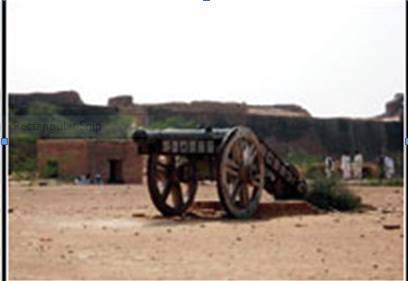

Earlier, the fort was closed to the public but not anymore. The fort walls are supported by enormous round buttresses, some of which are crumbling away. Once inside, one sees a number of buildings and structures, most of them in poor state. The exterior walls of the fort are more impressive than the inside: the bastions are made of burnt bricks and display geometric designs. Inside, a canon has been placed in the courtyard of the fort while, further along, one can see the retiring quarters of the royal family standing deserted, just like other complexes and structures that seem ready to fall any moment.

The general feeling one gets on visiting the place is that the site has been grievously plundered as a number of gaping holes lie at one’s feet. It was only at two places that one could witness some remnants of a grand life inside the fort. One was a wall behind some arches that still retained some of the white and blue patterns and the roof was inlaid with colourful patterns and beams of wood and bamboo.

Another structure situated on a slope, reached first by crossing a ramp and then a narrow stairwell, led to a room with an excellent view of the area. Bright and well-ventilated, this room has also retained most of its colourful wall painting, and exudes an aura of grandeur.

Beside the fort is the Derawar mosque, made of white marble and similar in design to the Moti Masjid in Delhi. Built by the nawab for his pir, Ghulam Farid, the mosque has three domes and four minarets. There is also a royal graveyard of the nawab’s family nearby, where tombs are again made of marble (glazed with blue tiles and patterns in some cases). Today, jeep and camel safaris can be taken into the desert from near the fort. However, the area needs more attention and efforts should be made to preserve what is left of the fort.

Merely holding the Cholistan Jeep Rally in March each year — this being the site where the rally converges — is not enough to mark the significance of the historical fort.