Citizenship: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be acknowledged in your name. |

The basics

The Constitution of India provides for a single citizenship for the whole of India. Every person who was at the commencement of the Constitution (26 January 1950) domiciled in the territory of India and: (a) who was born in India; or (b) either of whose parents was born in India; or (c) who has been ordinarily resident in India for not less than five years became a citizen of India. The Citizenship Act, 1955, deals with matters relating to acquisition, determination and termination of Indian citizenship after the commencement of the Constitution.

Citizenship, grant of

1950: “minorities” in the 1950 Nehru- Liaquat pact

J.P. Yadav | Nehru is BIG | Deal with it, Mr Half-Truth | Telegraph India

The word “minorities” in the 1950 pact between Nehru and his then Pakistan counterpart Liaquat Ali Khan:

The very first line of the Nehru-Liaquat pact mentioned “irrespective of religion”. The first line of the April 8, 1950, agreement reads: “The Governments of India and Pakistan solemnly agree that each shall ensure to the minorities through its territory, complete equality of citizenship, irrespective of religion, a full sense of security in respect of life, culture, property and personal honour, freedom of movement within each country and freedom of occupation, speech and worship, subject to law and morality.”

The pact also said: “Both governments wish to emphasise that the allegiance and loyalty of the minorities is to the State of which they are citizens, and that it is to the government of their own State that they should look for the redress of their grievances.”

A letter Nehru had purportedly written to the then chief minister of Assam, Gopinath Bordoloi, about a year before the 1950 pact. Nehru wrote: ‘You’d have to differentiate between Hindu refugees and Muslim migrants. You’ll have to take full responsibility of settling refugees’.

Nehru had purportedly written to Bordoloi in response to a letter from the Assam leader expressing concern over influx of people from the erstwhile East Pakistan.

Nehru in the Parliament, in 1950, said that ‘there is no doubt that the affected people who have come to settle in India deserve citizenship and if the law isn’t suitable then it should be modified’.”

2014-19: govt gave citizenship to 600 Pakistani Muslims from, 6 lakh SL Tamils

India Today Web Desk, Dec 17, 2019: India Today

600 Muslims from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh have been given citizenship by the Modi government in the last five years, Union Home Minister Amit Shah said while speaking at the Agenda Aaj Tak

New Delhi

Modi govt gave citizenship to 600 Muslims from Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh: Amit Shah

Union Home Minister Amit Shah claimed that around 600 Muslims from three neighbouring countries have been given Indian citizenships since 2014 when the Narendra Modi government first came to power. Shah also claimed that the Modi government has given citizenship to more than 6 lakh Sri Lankan Tamils.

"600 Muslims from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh have been given citizenship by the Modi government in the last five years," Shah also said. "We've given citizenship to over 6 lakh Sri Lankan Tamils."

2014-19

January 20, 2020: The Times of India

CHENNAI: Pointing out that states cannot refuse to implement the Citizenship (Amendment) Act as “that is against law and the Constitution”, Union finance minister said that as many as 2,838 Pakistanis, 914 Afghans and 172 Bangladeshis had been given citizenship in the past six years.

Reeling out statistics issued by the Union home ministry, the finance minister added that 391 Afghans and 1,595 Pakistanis had been given citizenship in the past two years. “Obviously, they include Muslims too,” Sitharaman said, while adding that 566 Muslims from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh were given citizenship since 2014.

Participating in a discussion organised by the Chennai Citizens’ Forum and New India Forum, Sitharaman said, "Political parties can make a political statement by passing resolutions against CAA in the assembly, but states cannot refuse to implement it." She said there was an attempt by the opposition to distort the truth and create fear about the CAA. “Every question that the opposition raised in Parliament about the CAA was answered…

The CAA is to offer citizenship and not to deny citizenship to anyone,” Sitharaman said.

The Citizenship Act of 1955 continues to remain in force and citizenship will continue to be given to people if they fulfill the conditions under the four categories — birth, descendency, registration and naturalization. “Just by bringing in changes and amendments does not make the existing categories go away,” she pointed out.

Sitharaman said the people who have been granted citizenship are the ones who had come to India from the then East Pakistan, which later became Bangladesh. “People like them had to be given citizenship and hence the amendment to the Citizenship Act,” she said.

She said the condition was very pitiable in camps where Sri Lankan Tamils live. “Political parties raising the issue for not granting citizenship (to Sri Lankan Tamils) will not talk about these. No human rights organisation will speak about them. Since 1964, more than four lakh Sri Lankans have been granted citizenship. Sri Lankan Tamils living in camps, around 95,000 of them, too will be given citizenship in the coming years,” she said.

Clarifying that the CAA had nothing to do with the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the National Population Register (NPR), Sitharaman said the NRC had been implemented in Assam as per the directions of the Supreme Court. “There have been no talks about the NRC being implemented across India and whether the process will be the same as done in Assam. There have been no talks at all.”

2014-19: 15k from B’desh among 19k granted citizenship

March 5, 2020: The Times of India

Over 15,000 Bangladeshis were among the nearly 19,000 foreign immigrants from neighbouring countries who were granted Indian citizenship between 2014 and 2019, the home ministry told Rajya Sabha.

Of the 18,999 foreigners given Indian citizenship by registration or naturalisation in the past six years, 15,036 were from Bangladesh (14,864 became Indian citizens on account of inclusion of 53 enclaves in Indian territory in 2015), 2,935 from Pakistan, 914 from Afghanistan, 113 from Sri Lanka and one from Myanmar, junior home minister Nityanand Rai said.

In 2019, the number of Pakistanis acquiring Indian citizenship was the highest in the past six years. As many as 809 Pakistani immigrants became Indian nationals last year, up from 450 in 2018, 476 in 2017, 670 in 2016, 263 in 2015 and 267 in 2014. The maximum number of Afghan immigrants were granted citizenship in 2014-2015, though the number fell to double digits after 2017. In 2018 and 2019, just 30 and 40 Afghanistan nationals were given Indian citizenship. TNN

2015- 2019

‘15k Bangladeshis among 19k given citizenship in 4 years’, February 5, 2020: The Times of India

As many as 21,408 foreigners were granted Indian citizenship in the last 10 years since 2010, the home ministry told the Lok Sabha.

In reply to a written question, junior home minister Nityanand Rai said that 19,008 foreigners were granted citizenship between 2015 and 2019, with the biggest batch comprising 14,864 Bangladeshis who were given Indian citizenship under Section 7 of the Citizenship Act, 1955 (citizenship by incorporation of territory) following signing of the Indo-Bangladesh land boundary agreement.

Under this agreement reached in 2015, 53 enclaves of Bangladesh were included in Indian territory.

In comparison, 2,400 foreigners were conferred citizenship of India between 2010 and 2014.

Rai further informed the LS that, as reported by the Bureau of Immigration, 445 Bangladeshi immigrants were deported in 2018, 51 in 2017 and 308 in 2016.

As per the data put out by the home ministry, 987 foreigners were granted citizenship in 2019, 628 in 2018, 817 in 2017, 1,106 in 2016, 15,470 in 2015, 617 in 2014, 563 in 2013, 553 in 2012, 425 in 2011 and 232 in 2010. Rai said the records of persons granted citizenship by registration or by naturalisation are not maintained religion-wise.

Citizenship for minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan

2011-18

Mostly Pakistanis On Long-Term Visas To Gain

Around 31,000 immigrants from minority communities of Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, granted long-term visa by India on grounds of ‘religious persecution’ and who have applied for citizenship, will be the immediate beneficiaries of the proposed amendments to the Citizenship Act. However, contrary to the perception that the bill will confer citizenship on a large number of Bangladeshi immigrants living in Assam, no more than 187 Bangladeshis were granted long-term visa from 2011 to January 8, 2019.

The majority of the beneficiaries may be Pakistani immigrants, with as many as 34,817 issued long-term visas between 2011 and January 8. The religion-wise break-up of Pakistani long-term visa holders was not available, though as per the report of the joint parliamentary committee (JPC) on Citizenship Amendment Bill, there were 31,313 migrants — 25,447 Hindus, 5807 Sikhs, 55 Christians, two Buddhists and two Parsis — from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh staying on long-term visas.

While 15,107 Pakistani longterm visa holders are living in Rajasthan, 1,560 are in Gujarat, 1,444 in Madhya Pradesh, 599 in Maharashtra, 581 in Delhi, 342 in Chhattisgarh and 101 in Uttar Pradesh.

As per the JPC report laid in both Houses of Parliament on January 7, Intelligence Bureau in its deposition before the committee had said 31,313 minorities from the three countries, granted long-term visa based on claims of ‘religious persecution’ and who had applied for citizenship, would be the immediate beneficiaries of proposed changes in the Citizenship Act.

However, it added that others who did not claim “religious persecution” at the time of their arrival in India would find it difficult to do so now. “Any future claim will be enquired into, including through RAW, before a decision (on grant of citizenship) is taken,” the IB director had told the panel.

He further hinted that even the 31,313 immigrants on long-term visa could be subjected to fresh security vetting.

2019, December

LS passes bill 311-80 at midnight

A heated, polarising debate on Monday marked the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) in the Lok Sabha after midnight with home minister Amit Shah repeatedly drawing a distinction between refugees fleeing religious persecution and infiltrators even while asserting an all-India national register of citizens (NRC) is on the anvil.

The CAB offers a path to citizenship for Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh on grounds of religious persecution with December 31, 2014, as the cut-off. The bill was passed by 311-80 votes.

Divisions sought by the opposition over amendments seeking removal of references to Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh and to make the legislation “religion-neutral” were defeated. Divisions sought by the opposition were negated by wide margins of 304-94, 311-12 and 312-09.

The stage is now set for a clash in the Rajya Sabha where the numbers are closer even as NDA seems to have requisite support with the backing of BJD, AIADMK, TDP and YSRCP. The government’s cause could be further assisted by abstentions. On Monday, Shiv Sena was the centre of attention with the party supporting the bill’s introduction, but setting out several caveats.

Introducing the bill, home minister Amit Shah denied that the legislation targeted any community or religion, saying its provisions do not affect the existing rights of any group. He also read out inclusions intended to keep Nagaland,

Mizoram and Meghalaya out of the bill’s purview. He added that Manipur will now be covered by the inner line permit system that imposes restrictions on non-locals. He also said exceptions for minorities, such as minority-run institutions, had been carved out earlier and this was not seen as a violation of the Constitution. “This bill is not even .001% against Muslims. It is against infiltrators,” he added.

Shah catalogued instances of what he called persecution: killings and rapes, forcible conversions and destruction of places of worship: of non-Muslims in the Muslim-majority countries of Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. The minister defended the CAB’s provisions for non-Muslims, reminding Congress’s Shashi Tharoor of the basis on which those who came to India after Partition were given citizenship.

Shah’s CAB push: Partition faith-based

The division of country was on basis of religion, that was the reason for citizenship (to refugees) then,” Shah said, adding that Muslims could not have been brought under the ambit of the legislation because they are not minorities in the three Islamic countries. He expressed the government’s determination to bring an all India NRC, saying that this will be done smoothly.

Shah pointed out that the Muslim population of India had increased while Hindus in Pakistan and Bangladesh had declined while they were vulnerable to rape and assaults with no safety of their rights. He also made it clear populations like Rohingya would not be covered by bills like CAB. “There will be no politics of protection...offering ration cards, documents.” He also said Article 371, which offers measures for the northeast is not comparable to Article 370. “There no separate constitution or flag under Article 371. I assure the northeast that Article 371will not be touched,” he said Countering the opposition, Shah said the view that the right to equality before law under Article 14 was violated by the CAB was incorrect, saying the

Constitution provided for reasonable classification and the non-Muslims in the three Islamic nations constituted a specific class. He said the bill is intended to ameliorate the conditions of those who have fled their homes and do not have the option to return. He played on the word “minority” to remind the opposition that it was term that often figures in its formulation, only this time it applied to those in countries covered by the bill.

He also responded to the criticism that bill had failed to cover Tamils who face persecution in Sri Lanka. Shah said that India had taken specific measures to help specific communities at different points in time, saying that citizenship was indeed offered to refugees in 1964. “ We also took in people from erstwhile East Pakistan in 1969 and from Uganda. This bill is designed to specifically help the minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan”.

He took a dig at Congress, saying, “This party partners Muslim League in Kerala and Shiv Sena in Maharashtra.” The treasury benches were led by Shah with PM Narendra Modi not being in the House.

The opposition, led by interventions by Congress’s Manish Tewari, Trinamool’s Saugata Roy and RSP’s N K Premchandran, accused the government of masking political motives and bringing a bill that is divisive and singles out one religious denomination. They also said the bill does not pass the test of constitutionality and must not be admitted or taken up for consideration by Parliament.

The government, however, received the support of north east states barring Sikkim, assured by Shah’s references.

The opposition also questioned how the grounds of religious persecution will be established, with DMK also asking whether Muslims seeking to come into India from Pakistan occupied Kashmir should not be considered eligible. Contrary to earlier indications, TRS opposed the bill while TDP and YSR-CP supported it. Other supporters of the bill include BJD which has a sizeable presence. BJP ally JD(U), which has often differed on Hindutva issues, said the bill should not be linked to secularism.

“Bill is meant to provide citizenship to those originally from here, no need to combine it with religion or other countries,” said JD(U)’s Rajiv Ranjan.

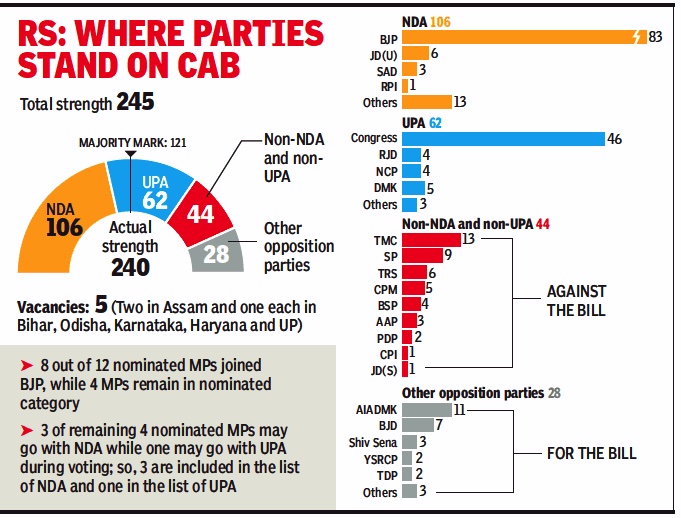

RS: Where the parties stand on the CAB

From: Dec 10, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Where the parties stood on the CAB in the RS

Will CAB legalise religious discrimination?

The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill touched off an expected storm in Lok Sabha on Monday after the BJPled NDA government introduced the proposed legislation that aims to extend Indian citizenship to specific categories of illegal migrants on the basis of religion. The contentious bill that seeks to amend the Citizenship Act, 1955, has been slammed for, among other reasons, discriminating against Muslims and for attempting to change the basis of citizenship for India. A look at the key questions it throws up

What is Citizenship (Amendment) bill?

The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill (CAB) passed in Lok Sabha seeks to change the basis of Indian citizenship by legalising religious discrimination. It seeks to amend the definition of illegal immigrant for Hindu, Sikh, Parsi, Buddhist and Christian immigrants from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh, who have lived in India without documentation. They will be granted fast-track Indian citizenship in six years. So far, 12 years of residence has been the standard eligibility requirement for naturalisation

What is the government’s logic?

The government’s logic is that these minority groups have come escaping persecution in Muslim-majority nations. However, the logic is not consistent – the bill does not protect all religious minorities, nor does it apply to all neighbours. The Ahmedia Muslim sect and even Shias face discrimination in Pakistan. Rohingya Muslims and Hindus face persecution in neighbouring Burma, and Hindu and Christian Tamils in neighbouring Sri Lanka. The government responds that Muslims can seek refuge in Islamic nations, but has not answered the other questions

Will it stand constitutional challenge?

Effectively, the CAB ringfences Muslim identity by declaring India a welcome refuge to all other religious communities. It seeks to legally establish Muslims as second-class citizens of India by providing preferential treatment to other groups. This violates the Constitution’s Article 14, the fundamental right to equality to all persons. This basic structure of the Constitution cannot be reshaped by any Parliament. And yet, the government maintains that it does not discriminate or violate the right to equality

Wasn’t partition also on basis of religion?

In Parliament, Amit Shah claimed that this would not have been necessary if the Congress has not accepted Partition on the basis of religion. However, India was not created on the basis of religion, Pakistan was. Only the Muslim League and the Hindu Right advocated the twonation theory of Hindu and Muslim nations, which led to Partition. All the founders of India were committed to a secular state, where all citizens irrespective of religion enjoyed full membership. Either way, this logic for the CAB also collapses because Afghanistan was not part of pre-Partition India

What about the North-East?

After the CAB faced resistance in the North-east, the region has been largely left out of its ambit. Areas under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution and states with an Inner Line Permit system won’t be part of CAB. Any person “declared foreigner” in these areas cannot apply for Indian citizenship even if he or she is from one of the six religious communities identified by the bill

What part does the Sixth Schedule play?

The Sixth Schedule lists special provisions for administration of North-east’s tribal areas, covering all of Mizoram and Meghalaya, and parts of Assam and Tripura. In Tripura, it’s the area under the jurisdiction of Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous Development Council. In Assam, it’s three small tribal-majority pockets in Dima Hasao, Karbi Anglong and Bodoland Territorial Area Districts. Since exemptions in CAB will only apply to these areas and not the entire state, it will add to the complexity of the incendiary politics of identity in the region

What is the Inner Line Permit system?

The Inner Line Permit (ILP) system draws legitimacy from a colonial-era law — the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873 — introduced to protect the economic interests of the British crown. To enter three states in the northeast — Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Mizoram — any outsider, including Indian citizens, needs an ILP. Only indigenous communities can settle, own land and get jobs in these areas. Because of these restrictions, which are already in place, the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill would not have applied to these states anyway. In the northeast, only Manipur remained outside the purview of both the ILP system and the Sixth Schedule and, therefore, the exemptions. On Monday, the Centre decided to extend ILP to Manipur as well

So, now a nationwide NRC?

The government wants a nation-wide register of citizens (NRC), as carried out in Assam. However, that exercise revealed the arbitrariness and mass exclusion of such a project, given the lack of paperwork that even citizens possess. If the CAB’s automatic immunity to Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, Buddhists and Christians is factored in, this will lead to widespread rights-stripping and isolation of Muslims.

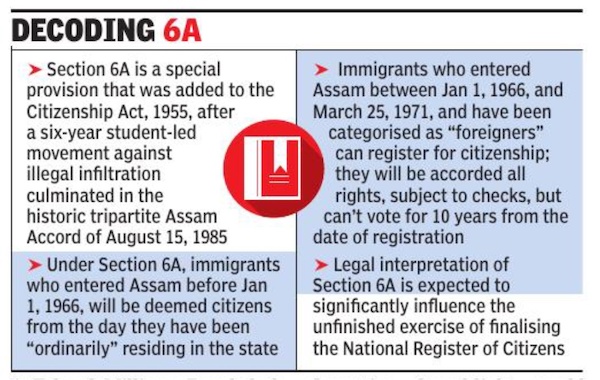

Citizenship Act, 1955: Section 6A

A backgrounder

Ajoy Sinha Karpuram, Oct 18, 2024: The Indian Express

Assam accord 1985 SC Verdict: In a landmark verdict, the Supreme Court on October 17, upheld the constitutional validity of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955, which granted citizenship to immigrants who entered Assam before March 24, 1971.

A five-judge Bench headed by Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud delivered the judgement. While reading out the verdict, the CJI said that while four judges, including himself, formed part of the majority verdict, Justice JB Pardiwala penned a dissent.

Section 6A was added to the statute in 1985 following the signing of the Assam Accord between the Rajiv Gandhi government at the Centre and the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), after a six-year-long agitation against the entry of migrants from Bangladesh into Assam.

The petitioners include the NGO Assam Public Works, the Assam Sanmilita Mahasangha, and others who claim that setting a different cut-off date for citizenship in Assam is a discriminatory practice.

What does Section 6A of the Citizenship Act provide?

A key element of the Assam Accord was determining who is a foreigner in the state. Clause 5 of the Assam Accord states that January 1, 1966 shall serve as the base cut-off date for the detection and deletion of “foreigners” but it also contains provisions for the regularisation of those who arrived in the state after that date and up till March 24, 1971.

Section 6A was inserted into the Citizenship Act to facilitate this. All persons of “Indian origin” who entered the state before January 1, 1966 and have been “ordinarily resident” in Assam ever since “shall be deemed to be citizens of India”. Additionally, it provides that anyone who entered and resided in Assam after January 1, 1966 but before March 24, 1971 who has been “detected to be a foreigner” would have the opportunity to register themselves according to rules made by the Central Government.

Following such registration, they would be granted the rights of citizens except that they would not be included in electoral rolls for the purposes of voting in elections for a period of 10 years. Those entering after March 24, 1971, would be considered illegal immigrants.

The verdict may also have an effect on the National Register for Citizens (NRC) in Assam. In 2019 a two-judge bench led by then CJI Ranjan Gogoi passed an order stating “We make it clear that subject to orders as may be passed by the Constitution Bench in Writ Petition (C) No.562 of 2012 and Writ Petition (C) No.311 of 2015, National Register of Citizens (NRC) will be updated.”

What did the court decide?

The majority opinion delivered by Justice Surya Kant (signed by Justices M M Sundresh and Manoj Misra) held that Parliament has the power to grant citizenship under different conditions so long as the differentiation is reasonable.

As the migrant situation in Assam was unique in comparison to the rest of India at the time, it was justified to create a law to specifically address it and doing so would not violate the right to equality under Article 14 of the Constitution. CJI Chandrachud pointed out in his separate but concurring opinion that the impact of immigration in Assam was higher in comparison to other states so “singling out” the state is based on “rational considerations”

Both the majority and CJI Chandrachud also held that the petitioners did not provide any proof to show that the influx of migrants affected the cultural rights of citizens already residing in Assam. Article 29(1) gives citizens the right to ‘conserve’ their language and culture. CJI Chandrachud stated that “Mere presence of different ethnic groups in a state is not sufficient to infringe the right guaranteed by Article 29(1)”.

The majority also held that the cut-off dates of January 1, 1966 and March 24, 1971 were constitutional as Section 6A and the Citizenship Rules, 2009 provide ‘legible’ conditions for the grant of citizenship and a reasonable process.

Justice Pardiwala on the other hand, in his dissenting opinion, held that the provision was unconstitutional and suffered from “temporal unreasonableness” as it does not prescribe a time limit for detecting foreigners and determining whether they were citizens. This, he held, relieves the government of the burden of identifying immigrants and deleting them from the electoral rolls which goes against the objective of providing citizenship while protecting the cultural and political rights of the people of Assam.

Further, he noted that there is no process for an immigrant to voluntarily be detected so if they fall in the timeframe provided under Section 6A. They must wait for the government to identify them as a “suspicious immigrant” before being referred to a foreigner tribunal for a decision, which Justice Pardiwala called “illogically unique”.

Why was Section 6A challenged?

The petitioner claim that the cut-off date provided in Section 6A is discriminatory and violates the right to equality (Article 14 of the Constitution) as it provides a different standard for citizenship for immigrants entering Assam than the rest of India — which is July 1948. The Assam Sanmilita Mahasangha (ASM), one of the lead petitioners in the case, argued that the provision is “discriminatory, arbitrary and illegal”.

They also claim that the provision violates the rights of “indigenous” people from Assam. Their petition, which was filed in 2012, states that “the application of Section 6A to the State of Assam alone has led to a perceptible change in the demographic pattern of the State and has reduced the people of Assam to a minority in their own State. The same is detrimental to the economic and political well-being of the State and acts as a potent force against the cultural survival, political control and employment opportunities of the people.” During the hearings, the petitioners argued that changing demographics in the state will affect the rights of “indigenous” Assamese people to conserve their culture under Article 29 of the Constitution of India.

What were the arguments in defence of Section 6A?

The Centre on the other hand has relied on Article 11 of the Constitution which gives Parliament the power “to make any provision with respect to the acquisition and termination of citizenship and all other matters relating to citizenship”. It argued that this gives Parliament the power to make laws on citizenship including for a “particular object” without violating the right to equality.

Other respondents, including the NGO Citizens for Justice and Peace, argued that if Section 6A is struck down a large swathe of current residents will be rendered “stateless” and be considered foreigners after enjoying citizenship rights for over 50 years. They also argued that the demographic pattern of the state changed in response to geo-political events even before Section 6A was introduced and that Assam has long since been a multi-lingual and diverse state.

SC, 2024

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Oct 18, 2024: The Times of India

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra, Oct 18, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi: In validating Section 6A of the Citizenship Act that conferred citizenship to Bangladeshi migrants entering India before March 25, 1971, Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud in his opinion said this cut-off date was reasonable as on that day Pakistan army had launched ‘Operation Searchlight’ to curb the Bengali nationalist movement in then East Pakistan.

Agreeing with the majority opinion of Justices Surya Kant, M M Sundresh and Manoj Misra on the validity of Section 6A incorporated in the Citizenship Act to honour the Centre’s commitment under the 1985 Assam Accord signed with students’ unions, CJI Chandrachud said application of the provision only to Assam had a reasonable nexus with the magnitude of the problem faced by the state due to unabated influx of illegal migrants from Bangladesh.

Quoting M Rafiq Islam’s book ‘A Tale of Millions: Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971’, the CJI said, “On March 25, 1971, the Pakistan army launched Operation Searchlight to curb the Bengali nationalist movement in East Pakistan. The migrants before the operation were considered to be migrants of partition towards which India had a liberal policy. Migrants from Bangladesh after the said date were considered to be migrants of war and not partition. Thus, the cut-off date of March 25, 1971, is reasonable.”

Referring to migrations from Bangladesh to India immediately after partition, the CJI said, “Since the migration from East Pakistan to Assam was in great numbers after the partition of undivided India and since the migration from East Pakistan after Operation Searchlight would increase, the yardstick has nexus with the objects of reducing migration and conferring citizenship to migrants of Indian origin (that is person born in undivided India).” Justice Chandrachud referred to the Sarbananda Sonowal judgment expressing concern over Assam facing “external aggression and internal disturbance” due to largescale illegal migration from Bangladesh and rejected the challenge to Section 6A’s validity based on the provision’s application only to Assam even though West Bengal, Meghalaya, Tripura and Mizoram shared longer borders with Bangladesh and faced illegal migrant influx.

“Though other states such as West Bengal (2,216.7 km), Meghalaya (443 km), Tripura (856 km) and Mizoram (318 km) share a larger border with Bangladesh as compared to Assam (263 km), the magnitude of influx to Assam and its impact on the cultural and political rights of Assamese and tribal populations is higher,” he said.

“The data submitted by the petitioners indicates that the total number of immigrants in Assam is approximately 40 lakh, 57 lakh in West Bengal, 30,000 in Meghalaya and 3,25,000 in Tripura. The impact of 40 lakh migrants in Assam may conceivably be greater than the impact of 57 lakh migrants in West Bengal because of Assam’s lesser population and land area compared to West Bengal,” the CJI said.

The petitioners, challenging the validity of Sec 6A, had argued that largescale entry of illegal migrants from Bangladesh and conferring them citizenship had jeopardised Assamese people’s fundamental right to protect and conserve their culture.

Rejecting this argument, the CJI said, “First, as a matter of constitutional principle, the mere presence of different ethnic groups in a state is not sufficient to infringe the right guaranteed by Article 29(1)… Second, various constitutional and legislative provisions protect Assamese cultural heritage.”

Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2019

Passed in Lok Sabha

LS okays plan to tweak citizenship law, January 9, 2019: The Times of India

ST Status Sop For 6 Assam Communities

Amid dissent from opposition, walkouts by Congress and Trinamool Congress, and allegations that the bill discriminated on religious lines, Lok Sabha passed the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2019 on Tuesday. It will now face the Rajya Sabha hurdle, where the larger bench strength of the opposition could stall its passage and eventual enactment.

The bill seeks to provide Indian citizenship to non-Muslims from Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan who have escaped religious persecution. It has faced allround resistance in Assam, including from NDA ally Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), which quit the BJP-led Assam government.

Piloting the bill in Lok Sabha, home minister Rajnath Singh asserted that the Centre would take all steps to protect the Assamese culture and traditions, but remained, at the same time, unapologetic about the need to give special protection to Hindus facing persecution in neighbouring countries.

Undercutting Congress’ arguments that the bill was discriminatory, Singh quoted former PMs Jawaharlal Nehru and Manmohan Singh to buttress his argument that India has the “moral obligation” to shelter refugees from neighbouring countries.

“They have no place to go to, except India,” Rajnath Singh said, adding that it was unfortunate that despite the Liaquat-Nehru Pact to protect minorities, it was not honoured as it should have been. Rajnath also asserted that “anyone eligible under the provisions under the law will be accorded citizenship”.

He also clarified that the government had acceded to the opposition demand for implementation of Clause 6 of the Assam Accord, to grant tribal status to six OBC communities — Tea Tribes /Adivasi, Tai-Ahom, Chutia, Koch-Rajbongshi, Moran and Motok. “A high level committee has been appointed to implement this,” he said, adding that a separate bill will be brought to grant ST status to Bodo Kacharis living in the hill districts of Assam and Karbis in the plains.

“Sixth Schedule of the Constitution is also proposed to be amended to strengthen the Autonomous District Councils,” he said.

In the House, the loudest opposition to the bill came from AIMIM MP Asaduddin Owaisi, who alleged the bill was made by those who supported the ‘Two Nation’ theory and was in contravention of various sections of the Constitution.

Congress said many states opposed the bill and demanded that it should be sent to a select committee, walking out after the government did not heed its demand. TMC’s Saugata Roy dubbed the proposed legislation “divisive” and “insidious” that goes against the basic tenets of the Constitution.

Why Assam, other NE states opposed the bill

January 9, 2019: The Times of India

• Why Assam is again in the vortex of pro- and anti- migrant politics

The immediate cause is the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016, seeking to facilitate granting of Indian citizenship for non-Muslim migrants from Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan on grounds of religious persecution. The bill stretches the cutoff date for granting citizenship to December 31, 2014 from March 24, 1971 as mentioned in the 1985 Assam Accord.

• How BJP justifies religion-based citizenship rules

BJP says such provisions will prevent Assam from being swamped by Muslims (or Jinnahs as Himanta Biswa Sarma, BJP’s face in the northeast, puts it). It believes Assam needs additional Hindu population to ensure Muslims cannot become a force reckon with in politics.

• Why there is so much resistance against the changes

In Assam, illegal migrants are not identified along religious lines and people want such migrants from Bangladesh, both Muslims and Hindus, who are incidentally Bengali-speaking, to be deported. The Assamese fear that illegal migrants from Bangladesh pose a threat to their cultural and linguistic identity.

• What is the general stand of Bengali-speaking people on the issue

In Bengali-dominated Barak Valley, most people welcome religion-based citizenship rules, which, they hope, will shield them from the National Register of Citizens (NRC). Until now, close to 40 lakh people have not found place on the NRC.

Bengali-speaking Muslims, who outnumber everyone else in at least eight districts of western and central Assam, are against the proposal to offer citizenship only to non-Muslim migrants. The minority-dominated AIUDF, headed by Bengali-speaking billionaire Badruddin Ajmal, supports the campaign launched by about 70 indigenous outfits, including AGP and Aasu, against the proposed bill.

In terms of percentage, Assam has the country’s second highest Muslim population after Jammu & Kashmir. Muslims, mostly Bengalispeaking, comprise 34% of Assam’s little over 3 crore people. Assamese-speaking Muslims, who are miniscule in number, support campaigns against migrants from all religious denominations.

• What steps have the Centre and BJP initiated to end the unrest

They propose to extend Article 371 of the Constitution and implement Clause 6 of the Assam Accord and to protect and preserve political rights, ethnic identity, cultural, literary and other rights of the state’s indigenous people. The use of Article 371, which has provisions for reservation of parliamentary and assembly seats for indigenous people, may upset Hindu Bengalis as well as Muslim Bengalis. Earlier, both had opposed the NRC.

• How other north-eastern states look at the new Citizenship Act

All NE states — Bengalimajority Tripura partially — are against it. Meghalaya and Nagaland, where the BJP shares power with regional forces, and Mizoram, where NDA ally MNF is in power, want a review. Mizoram fears Buddhist Chakmas from Bangladesh may take advantage of the Act. Meghalaya and Nagaland are apprehensive of migrants of Bengali stock. Groups in Arunachal Pradesh, where BJP is in power, fear the new rules may benefit Chakmas and Tibetans. Manipur wants the Inner-line Permit System to stop outsiders from entering the state. In Tripura, the BJP’s ruling partner, Indigenous People’s Front of Tripura, and opposition Indigenous Nationalist Party of Twipra are opposed to the Centre’s move.

• Possible political equations the region may see because of the new Act before the 2019 polls

AGP has quit NDA over the issue. The National People’s Party, BJP’s ruling partner in Meghalaya, does not rule out a similar action. BJP is hopeful that its plan to grant ST status to six Assam ethnic groups will take the wind out of the campaign against the new rules. These groups comprise 27% of Assam’s population and control 40 of the 126 assembly constituencies.

Why the NE is wary of the CAA

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Dec 16, 2019 Times of India

India’s journey as a nation began with the massive task of resettling a humongous number of refugees streaming in from Pakistan and East Pakistan. Refugees worked hard to establish themselves. Competition for land and preservation of culture became triggers for bloody violence between refugees and locals. It reverberated across north India.

A few West Pakistan refugee families were settled in Goran village in UP with cultivable land and plots for house. Skirmishes started as the cattle of the unwelcome refugees grazed on locals’ land. The Supreme Court in Balludin vs UP [AIR 1956 SC 181] records how mayhem followed on February 7, 1952, when enraged locals killed six male refugees in cold blood.

Things settled down for north India as the refugee influx was a one-time event. But north-eastern states are caught in a quagmire of continuous influx of refugees and illegal migrants since the 1960s from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), seriously threatening their rich culture and jeopardising the region’s unique demography.

Congress, in power at the Centre and most of the troubled N-E states, oversaw cooking of this dangerous potion for decades. It poisoned the social fabric and filled ‘original inhabitants’ of these states, particularly Assam, with suspicion, apprehending danger to their land, bread and identity.

Facing persecution and displacement by Kaptai Dam in East Pakistan, thousands of Buddhist Chakmas took refuge in Assam and Tripura in 1964. With Assam unable to cope with this massive influx, North-Eastern Frontier Agency (now Arunachal Pradesh) agreed to settle 4,000-odd Chakma families.

The 50-odd families settled in Gautampur and Maitripur in 1966 had swelled to 788 families by 1981 and encroached on 872 hectares in Miao district. When they sought citizenship encouraged by the Centre’s promises, the state government opposed it and asked them to vacate the encroached areas and get back to their allotted land.

The matter reached the SC [Arunachal Pradesh vs Khudiram Chakma, 1993 SCR (3) 401]. The SC rejected their claim for citizenship. It noted that they had been indulging in illegal procurement of arms and criminal activities to constantly trouble the locals.

The 4,000-odd Chakma refugee families of the 1960s had by 1991 grown into 65,000 units in Arunachal Pradesh. As their numbers grew, their relations deteriorated with the locals.

In August 1994, All Arunachal Pradesh Students Union (AAPSU) gave quit notices to Chakmas, asking them to leave the state by September 30, 1995, or face forced eviction. ‘Atithi Devo Bhava’ had transformed into ‘Atithi Tum Kab Jaoge’ (when will you leave, my guest). Assam inhabitants threatened to block Chakmas from entering their areas.

Three years after Khudiram Chakma case, the SC again dealt with the issue as the NHRC sought protection for Chakmas from AAPSU. The NHRC underlined the abject failure of Congress-led Centre and state governments to address grievances of locals and protect the refugees. In NHRC vs Arunachal Pradesh [1996 (1) SCC 742], the SC said, “State is bound to protect the life and liberty of every human being, be he a citizen or otherwise, and it cannot permit any body or group of persons, like AAPSU, to threaten Chakmas to leave the state.”

Importantly, the SC said, “No state government worth the name can tolerate such threats by one group of persons to another group of persons; it is duty bound to protect the threatened group from such assaults, and if it fails to do so, it will fail to perform its constitutional as well as statutory obligations.”

So true. Did the SC factor in that massive and continuous illegal Bangladeshi migration is irreversibly changing the demography of Assam and other N-E states to gradually undermine their identity and culture? The threat was not as overt as that by AAPSU but its effect is palpable on the ground.

A decade later, the SC realised it in Sarbananda Sonowal-I case [2005(5) SCC 665]. It termed the massive influx as an “external aggression” on Assam, severely criticised the Centre and the state government for adopting an ostrichlike approach towards the problem and struck down the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act. It ordered the Centre to form tribunals under the Foreigners Act to identify Bangladeshi migrants and deport them.

How did the Centre react to the SC judgment which said Bangladeshi migrants had overwhelmed the local population in border districts of Karimganj, Cachar and Dhubri? Vote-bank politics kicked in as foreigners tribunals fastpaced identification of Bangladeshis. The Manmohan Singh-led government nullified the judgment by amending the Foreigners Act to exempt only Assam from its purview.

The SC in Sonowal-II [2007 (1) SCC 174] angrily struck down the amendment. It ordered setting up of adequate number of foreigners tribunals to determine illegal migrants, keeping in mind the March 24, 1971, cut-off specified in the 1985 Assam Accord.

With the Narendra Modi government’s amended Citizenship Act setting a December 31, 2014, cut-off for accepting Hindu, Christian, Sikh, Parsi, Buddhist and Jain refugees as citizens, it is but natural for residents of Assam and other N-E states to apprehend a fresh attempt to legally settle many Bangladeshi migrants in their already crowded lands.

Assam and other N-E states for decades practised ‘Atithi Devo Bhava’ to accommodate refugees. Do not force them to violently ask ‘Atithi tum kab jaoge’? It is now the turn of politicians, bureaucrats, activists, lawyers and democratic institutions, each of whom function from acres of land in the national and state capitals, to practice ‘Atithi Devo Bhava’ by earmarking small portions of their sprawling residences for refugees. That will calm frayed tempers and growing apprehensions in NE states.

2024: The changes that the CA Act has brought about

March 12, 2024: The Times of India

Notification of Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019, rules, delayed by over four years, enforces CAA in the entire country. It is already in force in certain identified districts of nine states. The notification of rules will, in effect, fast-track citizenship to undocumented non-Muslim migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan for the rest of the country.

Where It’s Already In Force: Since 2022, govt has allowed 31 district magistrates and home secretaries of nine states to grant Indian citizenship to Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians who have come from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan under the Citizenship Act, 1955. These nine states are Gujarat, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi and Maharashtra.

According to MHA’s annual report for 2021-22, at least 1,414 foreigners belonging to these non-Muslim minority communities from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan were given Indian citizenship by registration or naturalisation under the amended Citizenship Act, 1955. Why It Was Delayed: The delay is mainly for two reasons: outbreak of mass protests in several parts of the country, leading to clashes between the agitators and the authorities, and the impact of Covid-19 pandemic that hit India in March 2020.

The Manual on Parliamentary Work says that the rules for any legislation should be framed within six months of Presidential assent or seek an extension from the Committees on Subordinate Legislation in Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha. Since 2020, the Union home ministry has been taking extensions at regular intervals.

What Happens Next: MHA has readied a portal for the convenience of applicants as the entire process will be online. Applicants will have to declare the year when they entered India without travel documents. No document will be sought from applicants, reports have quoted officials as saying. The law itself says that benefits under CAA will be given to undocumented minorities from the three neighbouring countries.

Where CAA Does Not Apply: The amendments introduced by CAA do not apply to areas covered by the Constitution’s sixth schedule. These are the autonomous tribal-dominated regions in Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram. This means migrants belonging to the identified communities from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan based on religion can’t be given Indian citizenship if they are residents in these areas.

CAA also does not apply to states with an inner-line permit (ILP) regime — primarily in North-East India. ILP is a special permit required for non-residents to enter and stay in these states for a limited period. ILP system is operational in Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Nagaland, Manipur, Lakshadweep and Himachal Pradesh.

What Changes With CAA: The provisions of Citizenship Act of 1955 barred illegal migrants in India. Such persons who entered India without valid travel documents or entered with a valid travel document but stayed beyond the permitted period were defined as foreigners and were meant to be deported. They were barred from obtaining Indian citizenship.

The government brought CAA as an enabling law for any Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, or Christian migrant — that is, the minorities — from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, or Pakistan if they left these “Islamic Re- publics” due to religious persecution and arrived in India before 2015. CAA also grants such migrants immunity from any legal proceedings for illegally entering India or exceeding their stay in India.

In the old law, a migrant had to live in India for “not less than 11 years” to qualify for citizenship. CAA reduced it to “not less than five years” for the persecuted minorities who are eligible.

Why Some Opposed CAA: The opposition to CAA has been on two premises — discrimination against Muslims and the potential spillover effect on the updation of the now-delayed National Population Register (NPR), 2020, and another contentious proposal of preparing the National Register of Citizens (NRC) at the state or national level.

Civil society criticised CAA, accusing the government of furthering its Hindutva agenda. CAA had come against the backdrop of an NRC exercise in Assam, where in June 2018, the draft list of citizens excluded about 20 lakh people as they failed to furnish documented proof of their original residency in the state.

The assemblies of at least six Congress and left-ruled states of the time — Punjab, West Bengal, Kerala, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh — passed resolutions against the implementation of CAA, urging the central govt to recall the amendments.

Assam Has A Different Case: The opposition to CAA in Assam stems primarily from concerns about its potential impact on the Assam Accord of 1985 and the NRC process.

Violation of Assam Accord: Singed between the Rajiv Gandhi government at the Centre and the leaders of the Assam Movement, a sixyear-long agitation against illegal immigration from Bangladesh, mandating the detection and deportation of individuals who entered Assam from Bangladesh after March 24, 1971. Opponents of the CAA argue that providing a path to citizenship for certain migrants contravenes the spirit of the Assam Accord, an emotive issue in the state.

NRC fallout: The SCmandated NRC process in Assam was completed in 2019 but it could not be implemented. The issuance of rejection slips to those excluded from the final list has not yet been carried out by the authorities. The state saw the resumption of antiCAA protests in Februaryend, adding to the complexities surrounding the CAANRC link.

How Govt Defended CAA: The govt maintains that Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians have faced religious persecution in Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan and need protection. Based on this argument, it has defended CAA on three principal grounds: Historical obligation: CAA supporters argue that India has a historical responsibility and moral duty towards persecuted minorities from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Humanitarian grounds: CAA was framed as a response to the plight of religious minorities facing persecution in the three neighbouring countries. These minorities deserve special consideration and assistance for the hardships they have faced in their countries of origin. Protection of religious minorities: CAA aims to provide a legal pathway to citizenship for religious minorities who may have entered India illegally or overstayed their visas, fearing persecution in their home countries. Granting them citizenship would offer them long-term security and protection from persecution.

CAA rules leave no room for states to process, decide pleas

March 13, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi:Even as CMs of West Bengal, TN & Kerala have decided not to implement Citizenship (Amendment) Act, state govts may have little leeway to block the Centre’s move to grant citizenship to minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, reports Bharti Jain.

The constitutional scheme of things puts central govt in charge of all such matters, with ‘citizenship, naturalisation and aliens’ figuring as entry no. 17 in the union list under the Seventh Schedule.

CAA panels can take final call on citizenship

Additionally, CAA Rules, 2024 have ensured that committees at the district level and state/UT level, tasked respectively to verify documentation and take a final call on citizenship, are packed with central govt officers, even as the state/ UT concerned is represented by a sole invitee to each committee. What’s more, the quorum of each committee shall be two, including the Chair. This practically means that the committees can do complete verification of applications and decide on grant of citizenship without mandatorily involving the state representative.

The Chair of both the empowered committee and the district-level committee are central govt officers. While EC will be headed by director (census operations) of the state/UT concerned, DLC will work under senior superintendent or superintendent of posts. The officer of director (census operations) reports to office of census commissioner and Registrar General of India. . The senior superintendent/superintendent of posts is an officer of the department of posts under central govt.

Along with the head, all members of EC — officer of subsidiary Intelligence Bureau, jurisdictional foreigners regional registration officer (FRRO), state informatics officer of NIC of state/UT and postmaster general of state/UT — are central govt officers. Of the two invitees to EC, only one is a state/UT govt representative and the other is from railways.

US and UN express concern about CAA

March 13, 2024: The Times of India

Washington: The US govt and the United Nations expressed concerns about the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019, with the UN calling the legislation “fundamentally discriminatory in nature.”

“As we said in 2019, we are concerned that CAA is fundamentally discriminatory in nature and in breach of India’s international human rights obligations,” a spokesperson of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights told Reuters. He added the office was studying whether the law’s implementation rules comply with international human rights law. The US has also signalled reservations. “We are concerned about the notification of CAA on March 11. We are closely monitoring how this act will be implemented,” a state department spokesperson told Reuters separately. “Respect for religious freedom and equal treatment under the law for all communities are fundamental democratic principles,” the spokesperson added.

The Indian embassy in Washington did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the state department and the UN human rights office reactions.

The Indian government denies the law is anti-Muslim and says it was needed to help minorities facing persecution in neighboring Muslim-majority nations. It has called the earlier protests politically motivated.

REUTERS

Court verdicts

Citizenship for India-born, -bred daughter of OCI card-holders: HC

May 18, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi : Delhi high court has asked the Centre to grant citizenship to a 17-year-old girl, raised in India to parents who held Overseas Citizens of India (OCI) cards and US citizenship at the time of her birth.

“The petitioner, despite having been born in India to two OCI card holders, educated in India and lived in India with her family, is unable to obtain a passport. These are clearly special circumstances as contemplated under Section 5(4) of the Act,” Justice Prathiba M Singh noted while referring to provisions of the Citizenship Act of 1955 and the Passports Act of 1967. Petitioner Rachita Francis Xavier had moved court challenging rejection of her plea for a passport. She informed the court that both her parents were earlier Indian citizens. However, they acquired US citizenship by 2005 and hence her parents were not Indian citizens on the date she was born.

The petitioner submitted that she is not an illegal migrant and qualified as a person of Indian origin entitling her to citizenship by registration. HC saw merit in the plea and noted that her circumstances would be covered under Explanation 2, as both parents of the petitioner were Indian citizens who had later obtained US citizenship.

The court pointed out that even OCI card holders are free to stay in India and can also rear their families, noting that in Xavier’s case the parents were OCI card holders when she was born and she has continuously stayed in India since birth. She has been educated in India and now sought a passport, HC said.

It allowed the plea and permitted the girl to apply for registration as a citizen under Section 5 of the Citizenship Act.

Person born at mother’s house in Pakistan

Swati Deshpande, 50 yrs on, ‘Pak man’ set for Indian citizenship, June 3, 2018: The Times of India

Six months after the Bombay high court directed the Indian government to consider a citizenship plea made by a Pakistan-born man residing for 50 years in the city, the Mumbai collector administered him the oath of allegiance, the first step towards citizenship.

The court, while granting Asif Karadia (53) protection against deportation in January, had observed after hearing his lawyer Sujay Kantawala and government pleader Purnima Kantharia that it was a “unique case”. Karadia was born in Pakistan and came to India as a toddler. His father, Abbas, is an Indian citizen.

Karadia (L) came to India in 1967

Karadia’s dad got married in Guj in 1962

Asif Karadia’s father had got married in 1962 in Gujarat to a woman who had a passport from Pakistan, which said she was born in Mumbai. The HC observed that “though conceived in India, as per customs, his (Asif ’s) mother went to her parents’ place in Karachi where he was born on April 19, 1965.” Mother and child came to India in 1967 and have lived here since. Asif has been residing on long-term visas.

The father had filed the petition to seek Indian citizenship for his son after a deportation scare. Asif had applied for citizenship in March 2015. Their case was that under Section 5 of the Citizenship Act, Asif was eligible to be granted Indian citizenship. Article 5 of the Indian Constitution allows a person “either of whose parents was born in the territory of India” to become a citizen. Asif ’s name was stamped on his mother’s Pakistani passport after his birth. But in 1972, the Indian government granted citizenship to his mother after she surrendered her passport.

Detention centres

What are detention centres?

Ruchika Uniyal, Dec 25, 2019: The Times of India

PM Modi while addressing a rally on Sunday to assuage concerns over the Citizenship Amendment Act and a nationwide National Register of Citizens (NRC) said rumours were being spread that Muslims would be sent to such places. Soon after the speech, social media was flooded with images of detention centres under construction.

So what are detention centres?

• Detention centres are meant to house illegal immigrants after they are declared ‘foreigners’ by tribunals/courts or foreigners who have served their sentence for an offence in India and are awaiting deportation to their home country. Under Section 3(2)(c) of The Foreigners Act, 1946, the Centre has powers to deport foreign nationals staying illegally in India. States can also set up detention centres.

What do detention centres have to do with NRC?

• In Assam, the NRC is a list of residents prepared to identify bonafide residents and detect illegal migrants. In 2013, in response to a series of writ petitions, the SC directed the Registrar General of India to start the updating exercise. The process started in 2015 and the updated final NRC was released on August 31 this year, with over 19.07 lakh applicants failing to make it to the list. Non-inclusion in NRC does not automatically mean that someone is a foreigner. They are allowed to present their case before the foreigners’ tribunals which are quasi-judicial bodies that exclusively adjudicate matters of citizenship. The tribunal’s verdict can be challenged in the high court and, then, the apex court.

Which states have detention centres?

• In Assam, detention centres were first set up in 2005 by the Tarun Gogoi-led Congress government. Instructions have been issued to all states/UTs administrations in 2009, 2012, 2014 and 2018, for setting up detention centres as per requirement to restrict the movements of illegally staying foreign nationals so that they are available when deportation is ordered.

Assam has six temporary detention centres — in Goalpara, Tezpur, Jorhat, Dibrugarh, Silchar and Kokrajhar — set up inside district jails where government says 988 people are housed. One standalone detention centre is being built in Matia that will be India’s biggest with a capacity to house 3,000 inmates.

There’s one in Karnataka. The facility is yet to house anyone. Mumbai also had plans to set up a detention centre, but it is unlikely to see the light of day. Earlier this year, the Bengal government also gave its nod to build a detention centre each in New Town and Bongaon. There is one in Goa too and Delhi.

Are detention centres prisons? They aren’t supposed to be.

• Activists say it is essential to differentiate between those serving time for a crime and those in detention centres awaiting decision on whether they can stay in a country legally. A Model Detention Centre Manual sent to states this January by the Centre directs that detention centres should have modern amenities like skill centres, creche for children and a cell to help detainee foreigners contact the concerned mission/embassy/ consulate or their family through proper procedure. In May this year, the Supreme Court allowed those who have completed three years in detention camps to be released on bail after furnishing surety bonds of Rs 1 lakh each from two Indian citizens and biometric details. They have to report to the local police station regularly while they fight the legal battle to prove their citizenship in higher courts.

Biggest foreigner detention centre in Assam

Sep 7, 2019: The Times of India

Centre funding country's biggest foreigner detention centre in Assam

GUWAHATI: The country's biggest detention centre to house foreign convicts and people declared "foreigners" by tribunals, coming up in Assam's Goalpara district, will be operational early next year. Sanctioned by the Union home ministry in June last year, Assam's first detention centre is being constructed on 20 bighas (28,800 sq ft) of land at Matia, about 124km west of Guwahati, at an estimated cost of Rs 46.5 crore. The entire expense on the facility, with a capacity to house 3,000 detainees, is being borne by the Centre. Incidentally, Goa opened a detention centre for foreigners in May this year. In 2014, the Centre had asked all states to set up at least one 'detention centre/holding centre/camps' to detain "illegal immigrants and foreign nationals awaiting deportation/or repatriation after completion of sentence due to non-confirmation of nationality".

The objective was to separate declared foreigners from criminals in jails. Recently, the Supreme Court set the detention period of foreigners at 3 years. After completion of this period, those in detention would be eligible for bail after furnishing a surety bond of Rs 1 lakh each from two Indian citizens along with their proposed residential address and biometric details. Assam home commissioner and secretary, Ashutosh Agnihotri, said the Goalpara detention centre cannot be linked to the outcome of the final NRC.

"The camp will become operational early next year. But don't link it with NRC. In case of (dropouts), it has been already clarified (dropouts are not foreigners and can appeal in foreigners' tribunals). We do not know what policy comes after that," he added. He further said, "The Matia camp is only for those detainees who have been declared foreigners and are in the existing six detention camps (which are attached to state's six central jails), besides foreign convicts. Once it's ready, we'll shift these people here." There are 1,136 detainees in the six temporary detention camps located in the jails in Kokrajhar, Goalpara, Jorhat, Tezpur, Dibrugarh and Silchar. Last month, nine detainees, who completed three years in detention, were released on bail as per SC guidelines.

Further, 25 others have died in detention due to health issues. The Centre.

Assam detention centres set up on HC order

Prabin Kalita, Dec 24, 2019 The Times of India

Assam finance minister Himanta Biswa Sarma on Monday took it upon himself to explain why PM Narendra Modi was “very much correct” when he said at Delhi’s Ramlila Maidan on Sunday that the Centre hadn't set up any detention centre in the country. He pointed out that each of the six such camps that already exist in the state had been built on the orders of the Gauhati HC.

“The PM was very much correct because the central government has not set up any detention centre. The detention centres in Assam were set up exclusively on the basis of the high court’s orders. The Centre and the state government had nothing to do with it,” Sarma said.

There are six temporary detention centres in Assam that together house about 900 people — most of them either declared foreigners or convicted of living illegally in the state. These centres are attached to central jails in Kokrajhar, Goalpara, Jorhat, Tezpur, Dibrugarh and Silchar. The first detention camp was set up within the Goalpara central jail 10 years ago after it was found that illegal migrants declared as foreigners by tribunals invariably vanish into thin air, making it impossible for the police to trace them.

The country’s largest detention centre, currently under construction at Matia in Assam’s Goalpara district, will become operational early next year. Sanctioned by the Union home ministry in June last year, the detention centre is being constructed across a 20-bigha (28,800sq ft) plot about 124km west of Guwahati at an estimated cost of Rs 46.51 crore. The facility will house 3,000 detainees, including those declared foreigners and currently lodged in the six camps. Foreign convicts will also be kept there.

“The high court has ordered that detention centres be set up. Construction will, of course, have to be funded by someone — either the state or the Centre,” Sarma said.

The SC recently fixed the detention period for foreigners at three years. After completion of this period, those in detention become eligible for bail after furnishing a surety bond of Rs 1 lakh each from two Indian citizens along with their proposed residential addresses and biometric details.

2019: Karnataka opens its 1st detention centre

Maharashtra’s stillborn plans

Anil Gejji and BV Shivashankar, Dec 24, 2019 The Times of India

Contrary to PM Modi’s statement, Karnataka has already launched its first detention centre for illegal immigrants near Nelamangala, about 40 km from Bengaluru.

Addressing a rally at Ramlila Maidan in Delhi, Modi had said, while referring to the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC), that there are no detention centres in India. “We’ve opened the centre and it’s ready to house illegal immigrants,” RS Peddappaiah, commissioner, social welfare department, told TOI. A top state home department official confirmed the development.

The state government had planned to open the centre in January, but advanced it reportedly following a directive from the Union government. Since the centre has been operational only for a few days, no illegal immigrant has been lodged there yet. “The Foreign Regional Registration Office identifies illegal immigrants and sends them to the detention centre. We are ready to house them with necessary infrastructure and staff,” Peddappaiah said.

The government has converted a social welfare department hostel into a detention centre. The facility has six rooms, a kitchen and a security room, and it can house 24 people. Two watchtowers have been built and the compound wall is secured with barbed wire.

In November the state government had informed the Karnataka HC that it had identified 35 temporary detention centres in all districts of the state to house illegal immigrants. The submission came during a hearing of bail petitions of two illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

The government had said 612 cases were registered under the Foreigners Act and other laws against 866 persons of different countries.

Planned centre for aliens: Maha ex-CM

Former Maharashtra CM Devendra Fadnavis said there was a proposal to set up a centre to house those staying illegally in Maharashtra based on a letter from the Union home ministry, reports Abhijeet Patil. Fadnavis, who said the letter was sent to all state governments, had written to CIDCO to identify land in Navi Mumbai. “There are many foreign nationals whose visas have expired in Mumbai. They have to be deported to their country of origin,” he said.

Persecuted people from Bangladesh, Pakistan

Ease citizenship rules for them: Meghalaya HC

December 12, 2018: The Times of India

The Meghalaya high court has urged the PM, law minister and the Parliament to bring a legislation to allow citizenship to Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, Christians, Khasis, Jaintias and Garos who have come from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan without any question or documents. The 37-page judgment by Justice S R Sen was given on Monday while disposing of a petition filed by Amon Rana, who was denied domicile certificate.

The judgment observed that Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Christians, Parsis, Khasis, Jaintias and Garos are tortured even today in the three neighbouring countries and they have no place to go.

Although the Centre’s Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016 also seeks to make Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan eligible for Indian citizenship after a stay of six years, there was no mention of this bill in the court order.

The judge directed the Centre’s assistant solicitor general, Meghalaya high court, A Paul to hand over the copy of the judgment to PM, Union home and law ministers latest by Tuesday for their perusal and necessary steps to bring a law to safeguard the interest of the communities.

“I can simply say that the Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, Christians, Khasis, Jaintias and Garos residing in India, on whichever date they have come to India, are to be declared as Indian citizens and those who will come in future also to be considered as Indian citizens. The court said these communities may be allowed to come anytime to settle in India and the government may provide rehabilitation “properly” and declare them citizens of India.

2012/ CPM on minority community refugees from Bangladesh

In contrast to his party’s opposition to Citizenship Amendment Act, CPM’s Prakash Karat had drawn a distinction between minorities who came fr om Bangladesh due to historical circumstances and those driven by economic reasons in a letter to then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2012.

Karat, who was then CPM general secretary, had called for a “suitable amendment to Clause 2(i)(b) of the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2003, in relation to minority community refugees from Bangladesh”. He had noted that the Aadhaar drive was increasing insecurities regarding exclusion and deportation.

Pointing out that a majority of minority refugees were from Scheduled Castes like Namashudras and Majhi, he reminded Singh of a previous speech he had given in Rajya Sabha seeking a more liberal approach to citizenship to unfortunate people who had faced persecution in countries like Bangladesh.

“While we advocate a humane approach to all sections, on the specific issue of citizenship, we share the opinion you had advocated as leader of opposition when it was debated in Parliament in 2003,” he had said.

Karat pointed out that the NDA government in its amendment bill in 2003 did not differentiate between sections affected by proposed legislation. He quoted Singh as having said, “With regard to the treatment of refugees after the partition of India, minorities in countries like Bangladesh have faced persecution, and it is our moral obligation...circumstances force people, these unfortunate people, to seek refuge in our country, our approach to granting citizenship to these people should be more liberal.” Then deputy PM L K Advani had responded that he was fully in agreement with Singh’s views. Karat said Singh could take steps needed, included the amendment in law referred to, to bring relief to these unfortunate families, living across India.

Karat regretted that despite a consensus in Parliament, the matter remained pending. “This should have been followed by a suitable amendment in relation to minority community refugees from Bangladesh,” he wrote.

Proof of citizenship

Voter ID card, passport, yes; ration card, no/ 2019

Rebecca Samervel, Dec 15, 2019 Times of India

Holding that passports and voter identity cards are sufficient proof of citizenship, a magistrate court has acquitted a father and son accused of illegally entering the country from Bangladesh.

Mohamed Mulla (57) and Saiful (23) were arrested in 2017 after police received a tipoff about “Bangladeshi infiltrators” living at Shiva ji Nagar in Mumbai. The cops claimed they spoke in a language native to Bangladesh and could not produce sufficient documents to prove that they were Indians. But the duo presented Indian passports and voter ID cards in court.

“To my mind, the passport is a document sufficient to prove the nationality of Saiful. Similarly, the voter card or the election card used to be issued in favour of the voter on the declaration that he is citizen of India. The document is sufficient to prove the nationality of accused Mohamed,” said the court. It clarified that documents like ration card, Aadhaar and other IDs are not enough to prove nationality.

FATHER, S0N FREED

Ration card no proof of citizenship: Court

While Aadhaar card does not confer any right or proof of citizenship, the ration card is issued only on “humanitarian grounds” for protecting the persons from starvation and cannot be termed as proof of citizenship. “However, at the time of issuance of passport, the authorities verify the nationality and other relevant factors of the applicant,” said the court.

Ruling in favour of the Mullas, the court held that police had not produced any evidence to show that the documents — passport and voter ID card — were fabricated or forged. “I have arrived at the conclusion that the prosecution miserably failed to prove that the accused persons are foreigners and that they had entered India through unauthorised routes without holding valid documents,” said the court.

The prosecution had submitted that at the time of being booked in June 2017, the Mullas had “admitted” that they are Bangladeshis and had come to India without passports through an unauthorised route to escape poverty. Hence, they were booked under the Passport (Entry into India) Rules and the Foreigners Order. The court said no written confession was given by the accused before any judicial authority. “The confession before police is not admissible evidence,” it pointed out.

A Mumbai court held that passport authorities verify nationality while voter cards are issued after a declaration that the holder is a citizen of India

Voter ID is not conclusive proof: Gauhati HC

An electoral photo identity card cannot be treated in isolation as conclusive proof of citizenship in the context of the Assam Accord, the Gauhati HC has said while invoking a 2016 ruling to dismiss a petitioner’s claim to being Indian by virtue of his name being on a voters’ list.

The division bench of Justice Manojit Bhuyan and Justice Parthivjyoti Saikia made the observation in the case of Munindra Biswas, who had filed a writ petition challenging the decision of a foreigners tribunal to declare him a foreigner last July. Biswas had claimed that he was Indian by birth and a permanent resident of Margherita town of Tinsukia district. He submitted the voters’ list of 1997, which includes his name, as proof of his citizenship.

According to Biswas, his grandfather hailed from Nadia district of West Bengal and his father migrated from there to Assam in 1965 and settled in Tinsukia. The petitioner submitted to the tribunal a registered sale deed for a plot of land purchased by his father in Tinsukia in 1970, but the tribunal refused to accept that as proof of the latter being a resident of Assam.

The high court observed that since no voters’ lists prior to 1997 were submitted by the petitioner, the tribunal was right in deducing that he failed to prove his parents entered Assam prior to January 1, 1966 (the first cut-off in the accord).

“Regarding electoral photo identity card, the court in the case of Md Babul Islam versus state of Assam (2016) had held that a photo identity card is not a proof of citizenship,” the bench said.

Can’t pick anybody randomly, ask for citizenship proof: SC

AmitAnand Choudhary, July 12, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi : Noting that while Section 9 of the Foreigners Act outs the burden on an individual to prove he/she is not a foreigner, Supreme Court, in an important ruling, has held that this does not mean govt can pick a person at random, knock on their door, and demand they prove their citizenship. There must be some material against the person before proceedings under the law can be initiated, it stressed.

A bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Ahsanuddin Amanullah held that “in the absence of the basic/primary material, it cannot be left to the untrammelled or arbitrary discretion of the authorities to initiate proceedings”, which have life-altering and very serious consequences for the person. It said, Section 9 could not be invoked on the basis of hearsay or bald and vague allegation(s).

“...the question is that does Section 9 of the Act empower the executive to pick a person at random, knock at his/her/ their door, tell him/her/they/ them ‘We suspect you of being a foreigner’?... Obviously, the State cannot proceed in such a manner. Neither can we as a court countenance such an approach,” the bench observed, while setting aside the order of the Foreigners Tribunal and Gauhati high court declaring a person from Assam an illegal Bangladeshi migrant.