Contempt of court: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be acknowledged in your name. |

What is or is not contempt

“Criticising judges is not a crime”

Feb 10 2015

Markandey Katju

Contempt law threatens freedom.

Judges are meant to serve the people, criticising judges is not a crime.

In a recent judgment, a bench of the Indian Supreme Court convict ed a Kerala ex-MLA for contempt of court for calling some judges fools, and sentenced him to four weeks imprisonment.

In my opinion this judgment is incorrect, totally unacceptable in a democracy, and violates the freedom of speech guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India.

In a democracy the people are supreme and all authorities, whether President or Prime Minister of India, other ministers, judges, legislators, bureaucrats, police, army and so on are servants of the people. Since the people are the masters and judges their servants, the people have a right to criticise judges just as a master has the right to criticise his servant.

Why should Indian judges be so touchy? When the House of Lords delivered the judgment in the 1987 Spycatcher case, a prominent newspaper published as its headline “You Fools“.

Fali Nariman, the eminent Indian lawyer, was in London at that time and he asked Lord Templeman who had delivered the majority judgment why the judges did not take action for contempt of court.Lord Templeman smiled, and said that judges in England do not take notice of such comments.

In Balogh vs Crown Court, a case contested in England in 1975, the defendant told the judge “You are a humourless automaton. Why don't you self destruct?“ The judge smiled, but took no action.

In my opinion the Supreme Court judges, before convicting the former Kerala MLA, should have reminded themselves of the following words of the celebrated Lord Denning in R vs Police Commissioner (1968): “Let me say at once that we will never use this jurisdiction to uphold our own dignity .That must rest on surer foundations.Nor will we use it to suppress those who speak against us. We do not fear criticism, nor do we resent it. For there is something far more important at stake. It is no less than freedom of speech itself.“

A basic defect in the law of contempt of court in India is that it is uncertain.Nariman described it as “dog's law“. The British jurist Bentham said that when a dog does something nasty you beat it.Similarly, the law of contempt of court is known only when someone is punished, and thus it is a standing threat to freedom of speech.

We may consider an example. In Duda's case (1988) the facts were that a Union cabinet minister had said that the Supreme Court sympathised with zamindars and bank magnates. He further said “FERA violators, bride burners, and a whole horde of reactionaries have found their haven in the Supreme Court“ and that Supreme Court judges have “unconcealed sympathy for haves“.

A contempt of court petition was filed against the minister but no action was taken by the Supreme Court. Nariman wondered whether, if the statement was made by a common man and not a minister, that person would have gone unpunished.

But in the case against EMS Namboodiripad, former chief minister of Kerala, he was convicted for contempt of court for saying that courts were biased in favour of the rich, which is practically the same thing that was said by the Union minister in Duda's case.

Where then is the certainty and consistency in the law of contempt of court? Is it not “dog's law“ as Bentham called it? Moreover, it is settled law that contempt jurisdiction is discretionary jurisdiction. In other words, a judge is not bound to take action even if contempt of court has indeed been committed.Personally in my 20 years' career as a judge i dismissed perhaps 99% of contempt petitions, saying i was not inclined to take any action.

I remember once when i was sitting in my chamber at lunchtime in the Madras High Court, two senior judges came to meet me looking very upset. It appeared that a leaflet had been circulated against them calling them fools.

On reading the leaflet i started laughing. At this they got even more upset, and said to me, “Chief, we have been defamed, and you are laughing.“

I replied, “Look, you better learn how to ignore all this, or you will get blood pressure. So many things are said in a democracy and you must develop a thick skin, as these are occupational hazards.“

At this the judges tore up the leaflet and also started laughing.

History, issues

Dec 4, 2022: The Times of India

Should the judiciary be subject to criticism? This should be a rhetorical question. But criticism of the judiciary is circumscribed. As everyone knows, and as the Constitution states, the right to free speech (Article 19) isn’t absolute. It is constrained and that restriction includes “contempt of court”. The insertion was debated in Constituent Assembly debates on October 17, 1949.

Those who write on this are likely to quote R K Sidhva from those debates. “…In cases of contempt of court, the high court judge is the prosecutor and he himself sits and decides cases in which he himself has felt that contempt of court has been committed… After all, judges have not got two horns; they are also human beings. They are liable to commit mistakes. ” Beyond Article 19(2), there are Articles 129 and 215. The first permits the Supreme Court to punish contempt of court of SC, the second permits high courts (HCs) to punish contempt of court of HCs. Add to that Entry 77 in Union List and Entry 14 in Concurrent List. (1) What is contempt? (2) Who decides there has been contempt? (3) Who punishes? All three are important questions and (2) and (3) are related.

There were earlier Contempt of Court Acts (CCAs), in 1926 and 1952. But today’s law, based on the 1963 H N Sanyal committee on contempt law, is the 1971 statute. In common parlance, by contempt, we understand disobedience of court orders and interference with administration of justice. There have been quite a few cases of such contempt, when aspersions have been cast on specific judges, or mala fide motives attributed. The law separately defines these as civil and criminal contempt. “Civil contempt means wilful disobedience to any judgment, decree, direction, order, writ or other process of a court or wilful breach of an undertaking given to a court. ” This is what we normally understand by contempt and indeed, such action should be treated with contempt and chastisement. All jurisdictions have such provisions and there is less subjectivity for civil contempt. However, common law jurisdictions, unlike civil law jurisdictions, also have provisions on criminal contempt, inherently more subjective.

The 1971 statute defines it thus. “Criminal contempt means the publication (whether by words, spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representations, or otherwise) of any matter or the doing of any other act whatsoever which — (i) scandalises or tends to scandalise, or lowers or tends to lower the authority of, any court; or (ii) prejudices, or interferes or tends to interfere with, the due course of any judicial proceeding; or (iii) interferes or tends to interfere with, or obstructs or tends to obstruct, the administration of justice in any other manner. ” One can understand that part about interfering with a judicial proceeding or administration of justice. What is this about a court being scandalised? The language, imported and implanted from elsewhere, is courtesy the Sanyal committee. The cognoscenti will know it was imported from Britain and those fond of quoting case law will quote the 1899 McLeod versus St Aubyn case.

In that case, the judicial committee of the privy council actually said, the scandalising provision has “become obsolete in this country. Courts are satisfied to leave to public opinion attacks or comments derogatory to them. ” In other words, scrap that provision.

But, it also said, in a bit less quoted, “In small colonies, consisting principally of coloured populations, the enforcement in proper cases of committal for contempt of court for attacks on the court may be absolutely necessary to preserve in such a community the dignity of and respect for the court. ” In other words, retain it for a colony like India, as we have continued to do. The cognoscenti should know Britain has now done away with these scandalising provisions. In 2012, UK Law Commission produced a report recommending abolition and the 2013 Crime and Courts Act did precisely that. (The last such case in Britain was in 1931. )

Our Law Commission disagreed. After all, we are a former colony. It felt (274th Report, 2018) that scandalising provisions should continue. CCA was amended in 1971 and 2006. Especially in 2006, defence has become easier. But the scandalous clause remains. Justice Krishna Iyer became a judge of Kerala HC in 1968 and a judge of SC in 1973. In between, he was a member of the Law Commission. How many lawyers and judges know he fell foul of CCA? This was a case in Kerala high court in 1983 (Vincent Panikulangara versus V R Krishna Iyer). Justice Krishna Iyer delivered a speech on judicial reforms and a case of criminal contempt was brought against him. The petition was dismissed and if one reads the judgment, Kerala HC favoured action against civil contempt. “Contempt may be committed by a person wilfully disobeying the order or process of court or wilfully committing breach of undertaking given to a court. ” It was more circumspect about criminal contempt, including scandalising. That vestigial organ is a scandal. We should get rid of it.

■ Bibek Debroy is chairman and Aditya Sinha is additional private secretary (research) of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister

This is part of an occasional series on legal reforms

Judges accountable to society, not scared of fair criticism

Judges accountable to society, not scared of fair criticism: SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra | TNN From the archives of The Times of India 2007, 2009

New Delhi: At a time when many feel sweeping contempt powers are stifling critical views of the judiciary, Supreme Court on Thursday signed a bold new approach saying judges are accountable to society and are not scared of fair and reasonable criticism of their judgments and public actions.

“In fact, fair and reasonable criticism must be encouraged as no one, including judges, can claim infallibility,” said a bench comprising Justices J M Panchal and A K Patnaik while dismissing a petition seeking initiation of criminal contempt proceedings against HRD minister Kapil Sibal for his remarks as a senior advocate 15 years ago expressing concern over the falling standards in the judiciary and the legal profession.

A relieved Sibal expressed his happiness over the broadshoulder stand taken by the apex court. For, SC showed remarkable resilience by taking Sibal’s statement as fair criticism of the judiciary and terming them as concerns of a senior advocate who has practised long in the apex court about the spread of corruption. It said Sibal’s critical remarks along with his suggestions to root out the malaise were nothing but representative of his constructive approach.

The petition seeking initiation of contempt proceedings against Sibal for his statement, which was meant to be published in a bar association souvenir, was filed by an advocate in the Punjab and Haryana High Court. The case was later transferred to the SC in 1997.

The SC noted that despite repeated notices, the petitioner did not appear before the apex court to assist in the hearing. But, it decided to go ahead with the hearing and look into the merits of the allegations given the importance of the issue.

SC lays down criterion for contempt/ 2021

June 4, 2021: The Times of India

The Supreme Court said contempt action can be proceeded only in respect of established wilful disobedience of the order of the court. A bench comprising Justices A M Khanwilkar and B R Gavai made the observation while discharging show cause notices to the authorities issued in respect of annulment of recruitment process of some employees of Uttar Pradesh Jal Nigam.

The apex court was hearing a batch of pleas challenging orders issued by the chief engineer of Uttar Pradesh Jal Nigam. The SC had directed the Uttar Pradesh chief engineer to comply with the judgement of the Allahabad HC of November 28, 2017 in a batch of writ petitions.

The chief engineer then issued orders thereby reengaging the petitioners and other appointees to their previous place of posting. However, with a caveat that the said appointment was subject to the liberty granted by this court and that no arrears would be paid by the respondent corporation.

This order of the chief engineer, according to the contempt petitioners, is “in the teeth” of the decision of the top court and, therefore, the respondents be proceeded for having committed wilful disobedience of the SC order. “In exercising contempt jurisdiction, the primary concern must be whether the acts of commission or omission can be said to be contumacious conduct of the party who is alleged to have committed default in complying with the directions given in the judgment and order of the court,” the bench said.

While examining the submissions of the petitioners,, the bench noted that the orders passed by the HC and the apex court do not contain explicit direction to reinstate the petitioners with continuity of service and back wages as such. PTI

Remarks against SC, CJI: Nishikant Dubey not punished / 2025

Srishti Ojha, May 9, 2025: India Today

The Supreme Court censured BJP MP Nishikant Dubey over his recent remarks targeting the judiciary and the Chief Justice of India (CJI) Sanjiv Khanna, calling them “highly irresponsible” and an attempt to “scandalise and lower the authority” of the top court.

A bench comprising CJI Sanjiv Khanna and Justice Sanjay Kumar, while hearing a plea for contempt proceedings against Dubey, observed that although it chose not to entertain the petition, the MP’s statements were “absurd,” “ignorant,” and made with the intent to undermine public trust in the institution.

Dubey had criticised the Supreme Court for hearing petitions challenging the Waqf Act, alleging that the court was “taking the country towards anarchy” and that the CJI was “responsible for civil wars” in India. These remarks, the Court said, reflected a “penchant to attract attention” and had “the tendency to interfere and obstruct the administration of justice.”

In its order, the Court made it clear that "any attempt to spread communal hatred or indulge in hate speech must be dealt with an iron hand." It stated unequivocally that hate speech cannot be tolerated, noting that it undermines the dignity and self-worth of targeted groups, fuels disharmony, and erodes the values essential to a multicultural society.

The bench also emphasised that imputing motives to constitutional courts displays a deep misunderstanding of the judiciary’s role under the Constitution. “The remarks made by the lawmaker show his ignorance about the role of constitutional courts and the obligations bestowed upon them,” the Court stated.

While refraining from initiating a contempt action, the Supreme Court explained that contempt powers are to be exercised with restraint. “Every commission of contempt need not erupt in an indignant committal or levy of punishment, however deserving it may actually be,” the bench observed. “Judges are judicious, their valour non-violent, and their wisdom deep-rooted.”

Reaffirming its trust in the public’s ability to discern biased and ill-intentioned critiques, the Court concluded: “Surely, courts and judges have shoulders broad enough and an implicit trust that people would perceive and recognize when criticism or critique is biased, scandalous and ill-intentioned.”

Contempt power protects rights of people, not court’s dignity: HC

Aug 22, 2021: The Times of India

Stating that the shoulders of its institution are “broad enough to shrug off such scurrilous allegations”, the HC of Bombay at Goa has declined to punish a man who allegedly made allegations on social media against the judiciary.

A bench comprising chief justice Dipankar Datta and Justice M S Sonak stated that the power to punish for contempt “is to be only sparingly exercised, not to protect the dignity of the court against insult or injury, but to protect and vindicate the right of the people so that the administration of justice is not perverted, prejudiced, obstructed, or interfered with”.

The bench held that the dignity and authority of its judicial institutions are “neither dependent on the opinions allegedly expressed by David Clever, nor can the dignity of our institution and its officers be tarnished by such stray slights or irresponsible content”.

The court made these comments in a petition filed by Kashinath Shetye stating that Clever, who is possibly based in the UK, committed criminal contempt of court by making false and scurrilous allegations against some judicial officers of the district judiciary, and uploading the content on Youtube and WhatsApp.

“Such content, allegedly uploaded by David Clever, is best treated with contempt, rather than in contempt, particularly since David Clever has neither bothered to cite any specific instances nor bothered to lodge any complaints backed by even prima facie, credible material,” said the HC. “The inquiries made on our administrative side revealed the irresponsibility of the comments and the possible use of the uploader as a front by some disgruntled litigants. To take this matter any further might only serve to feed the publicity craze of those that have uploaded this content to provoke, rather than out of some concern to bring to the fore some genuine grievance concerning the administration of justice in Goa.” TNN

Corruption in judiciary, if alleged

Surveys on corruption in courts can invite contempt

The Supreme Court has made it very risky for any organisation to publish a survey on alleged corruption in the lower judiciary . The court said on Tuesday that the law permitted one or many trial courts to make a reference to a high court to launch contempt proceedings against those responsible for the embarrassing findings.

This ruling came in an 11year-old case filed by Transparency International India (TII) and Centre for Media Studies (CMC), which, along with their top management, were asked by a magistrate in Kangan, J&K, in 2006 to show cause why contempt of court proceedings or action under criminal defamation provisions of the Ranbir Penal Code (RPC) should not be initiated against them.

The magistrate had taken objection to an article in the `Greater Kashmir' daily that quoted a survey , conducted by CMS and published by TII, on “rampant corruption“ in the subordinate judiciary. But neither TII's nor CMS's representatives appeared before the magistrate, who, later the same year, is sued bailable arrest warrants against their brass.The warrants were stayed by the SC in 2006 itself.

On Tuesday , a bench of Chief Justice J S Khehar and Justice D Y Chandrachud and Justice Sanjay K Kaul rejected senior advocate Jayant Bhushan's argument that the survey was conducted by asking litigants about their experience in court and projected the general state of affairs in subordinate courts without branding any single trial court or judge.

Bhushan said, “The magistrate against whom the contemptuous remarks or allegations were made, he alone could have initiated proceedings to refer contempt proceedings to the HC.It was a general survey on the health of judiciary . If the Kangan magistrate's decision is upheld, then it would mean any or every magistrate throughout the state can initiate such proceedings.“

The CJI said, “If I am a trial court judge and you publish a survey projecting that 90% (of the) people feel the judiciary is corrupt, then I will think it is an aspersion on my integrity . I will be fully within law to issue notice to you and seek your reply on referring contempt proceedings to the HC.“

However, the SC said the magistrate exceeded his powers in issuing bailable warrants to secure the presence of TII and CMS officials. It gave two months to TII and CMS officials to either appear personally or through their counsel before the Kangan magistrate's court, and show cause why such proceedings should not be initiated.

The SC also said the petitioners were at liberty not to appear before the court, which could proceed with the case and pass orders on referring the contempt proceedings to the HC. On Bhushan's argument that the trial court did not have power to initiate criminal defamation proceedings under sections 499500501 of RPC, the SC said the petitioners could challenge any such order before the J&K HC.

Apology

Late contempt apology may lead to jail

Late contempt apology may lead to jail, says SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra | TNN

From the archives of The Times of India 2007, 2009

New Delhi: In contempt of case proceedings, it is better to apologise unconditionally and that too swiftly. Any dithering could land the accused in jail, the Supreme Court has warned.

“An apology in a contempt proceeding must be offered at the earliest possible opportunity,’’ said a bench of Justices G S Singhvi and A K Ganguly in an order which toughens the already stringent laws dealing with criminal contempt of court. Criminal contempt of court is a higher degree of offence compared to civil contempt and is invoked against those who seek to brazenly slander a court’s reputation.

Justices Singhvi and Ganguly, however, stressed that the courts needed to exercise the power to punish for contempt with restraint. “Contempt power has to be exercised with utmost caution and in appropriate cases,’’ it said, explaining why the contempt power has not been vested in lower courts. They have to make a reference to the concerned HC for initiation of contempt against a person for his contemptuous behaviour. ‘No contriteness in belated apology’ New Delhi: Toughening its stand against contempt of court, an SC bench rejected a delayed apology by one Ranveer Yadav, who was sentenced to two months imprisonment and fined Rs 2,000 for creating a ruckus in a court in Bihar’s Khagaria forcing the trial judge to leave the room.

His apology came long after trying to justify his misbehaviour on the grounds that the other accused in the case had provoked him. His misconduct was aggravated by his earlier misdemeanour of being discourteous to public prosecutors. Rejecting his apology, the bench has said: “A belated apology hardly shows the contriteness which is the essence of the purging of a contempt. Apart from belated apology, in many cases such apology is not accepted unless it is bona fide.’’

Terming Yadav’s act as a clear case of criminal contempt on the face of the court, the bench said the court reserved the right to reject any apology if it suspected its bona fide. “It’s not incumbent upon the court to accept the apology as soon as it is offered. The court must find out that it is bona fide,’’ Justice Ganguly said.

Contempt of court by judges

Petitions have been filed against judges, though rarely

From the archives of The Times of India 2007, 2009

Contempt of court, which puts the fear of the judiciary into litigants and lawyers, has also been used against judges, though very rarely

Jyoti Punwani

Abbas Kazmi, the former lawyer of Pakistani gunman Ajmal Kasab, filed a contempt of court petition against Judge M L Tahiliani, the additional sessions judge presiding over Kasab’s trial. On November 30, 2009, the judge had dismissed him for “not cooperating’’ and ordered him to leave the court forthwith. By “humiliating’’ him for doing what Kazmi regarded as his duty, the judge had committed contempt of his own court, says Kazmi’s petition.

Contempt proceedings against litigants, lawyers and journalists are a dime a dozen. But contempt proceedings against a judge?

Section 16 of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, applies specifically to “judges, magistrates or other persons acting judicially’’. They are liable for contempt of their own court or any other court in the same manner as any other individual, except when they make observations while hearing appeals against judgments passed by lower courts.

Contempt of court is invoked when someone acts in a way that scandalizes the authority or lowers the dignity of a court or interferes in the due course of a judicial proceeding or in the administration of justice. There have been very few cases where this law has been invoked against judges, and fewer still where convictions have resulted.

The reasons are two-fold, says Justice (Retd) B N Srikrishna. “First, lawyers and litigants are scared of annoying judges by filing cases against them. Second, and more important, judges are a dignified lot who know how to maintain the dignity of the court and ensure that the court is not brought to ridicule,’’ he says.

But lawyers recall instances where judges have thrown papers at them. In a 1973 case, a member of the UP Revenue Board, a quasi-judicial authority, was alleged to have abused a lawyer appearing before him with the words “Nalayak gadhe saale ko jail bhijwa doonga; kis idiot ne advocate bana diya hai?’’ and to have ordered the court peon to throw the lawyer physically out of the court. The lawyer filed a contempt of court petition in the Allahabad high court against the member, saying that he deserved to be punished “to save the dignity, honour and decorum of his court’’.

The high court issued notice to the member, who appealed to the Supreme Court on the question of procedure. Upholding the procedure, the Supreme Court sent it back to the high court to be decided on merits. But there is no mention in law journals whether he was convicted.

“Judges don’t normally behave like this,’’ says Justice (Retd) P B Sawant, “but this section serves as a warning to them.’’

Supreme Court lawyer Prashant Bhushan says that contempt proceedings against judges are rare because “one would have to show that an act purported to have been done by a judge in the judicial discharge of his duty was deliberately mala fide and calculated to obstruct the administration of justice or that his remarks were scandalous, which is difficult to prove’’. Bhushan reiterates Justice Srikrishna’s opinion—that people are wary of taking on judges and adds that it is an uphill task. “Even if one wants to file an FIR against any high court judge, even in corruption matters, one needs written permission from the Chief Justice of India,’’ he says. “We are still waiting for permission in many such cases.’’

In a 2007 case, Delhi high court judge V B Gupta found the order of a sessions court judge amounting to contempt of court, and said as much in his order. The sessions judge had issued a warrant of arrest against an accused meant specifically for absconders, although the accused’s bail application was pending. So angered was Justice Gupta by this order that he ordered the sessions judge to go back to law school. “Since Mr R K Tewari does not have even elementary knowledge of the Code of Criminal Procedure, under these circumstances it would be appropriate if he undergoes a refresher course at the Delhi Judicial Academy in criminal law and procedure for three months. Director, Delhi Judicial Academy, should submit to this court the performance report with regard to this judicial officer,’’ said Justice Gupta’s order. However, contempt proceedings were not actually filed against the sessions judge.

There is one case, however, where a judge was actually sentenced for contempt—but the action was initiated by a higher court. District judge Baradakanta Misra was suspended by the Orissa high court in 1972. He challenged his suspension in a letter to the governor, wherein he ascribed mala fide upon the high court, describing it as “an engine of oppression’’.

He made similar allegations in letters written to the registrar. In 1973, Judge Misra was convicted by a full bench of the Orissa high court, on six counts of contempt, and sentenced to a fine and two months’ imprisonment. What’s more, his conviction was upheld by the Supreme Court, which reduced his sentence, considering that he was at the end of his career, to a fine of Rs 1000, or, in default, three months’ imprisonment.

But this was a rare case. So why did Abbas Kazmi choose to file a contempt petition? “I have put my career at stake because of my izzat. I cannot tolerate it when people point fingers at me and say: ‘You were the lawyer thrown out by the judge’. I was simply doing my duty as a defence lawyer.’’

Dissent against judgements

Some cases

Dhananjay Mahapatra, September 3, 2018: The Times of India

Dissent in a pressure cooker democracy: Some brushed aside and some punished

Cambridge dictionary defines dissent as ‘a strong difference of opinion on a particular subject, especially about an official suggestion or plan or a popular belief’. Black’s law dictionary defines it as ‘contrariety of opinion, refusal to agree with something already stated or adjudged or to an act previously perfor med’.

There is a common strategy to silence dissent. First, drown the dissenter with abuse, followed by intimidation and finally, threaten with legal and illegal counter-action. Let us revisit some past incidents to try decoding Justice D Y Chandrachud’s recent quote, “Dissent is the safety valve of democracy. If you muzzle democracy, the pressure cooker will burst.”

In March 2004, Justice Arijit Pasayat had pummelled Gujarat government by likening it to “modern day Neros” for alleged machinations to derail the 2002 post-Godhra riot cases trials in the ‘Zahira Habibulla H Sheikh vs Gujarat’ judgment [2004 (4) SCC 158]. Social activist Teesta Setalvad had taken pains to help Zahira then.

Less than two years later, Best Bakery case’s star witness Zahira was back in the SC accusing ‘saviour’ Setalvad of “intimidating, threatening and coercing” her to “depart from the truth and depose in a manner which did not reflect the reality”.

While a Special Investigation Team probed riot cases, the then SC registrar general inquired into Zahira’s flipflop and castigated her both for perjury and financial immorality, which became the basis for the SC to convict and sentence her to jail.

During the SC-monitored probe, the SIT filed many status reports. One in 2009 contained allegations about how witnesses were ‘tutored’ by Setalvad and advocate Tirmiji and how exaggerated tales of riot survivors were circulated to make even stones weep.

Former Union minister P Shiv Shankar had employed vituperative language to register dissent against landmark Golaknath, Keshavananda Bharti and R C Cooper judgments. Attacking the apex court, he had said, “Anti-social elements — FERA violators, bride burners and a whole horde of reactionaries — have formed their heaven in the SC.”

In the contempt case against him — P N Duda vs P Shiv Shankar [1988 (3) SCC 167] — the SC took the minister’s dissent in its stride and termed the outburst as harmless opinion on the apex court’s endeavour to uphold rule of law.

In March 2002, celebrated author Arundhati Roy was convicted for contempt for a much milder criticism of the SC. Apart from accusing the SC of being partial and biased, she had said in her affidavit, “Indicates a disquieting inclination on the part of the court to silence criticism and muzzle dissent, to harass and intimidate those who disagree with it.” This charge from Roy against the SC contrasts with Justice Chandrachud’s recent outburst against the government on muzzling dissent.

Last but not the least, there is loud dissent in the SC corridors about the privilege accorded to a few famous lawyers as against the rebuffs reserved for lesser minions. It is about the SC’s tradition and convention not permitting advocates to mention and seek urgent hearing of petitions before the CJI, when he is heading a constitution bench.

In August 2007, a constitution bench headed by then CJI K G Balakrishnan carved out an exception for senior advocate Fali S Nariman when he mentioned and sought urgent hearing of interim bail plea for Sanjay Dutt in Mumbai serial blasts case after the trial court convicted him. The request was accepted and the plea was heard a few days later.

Similar courtesy was extended to senior advocate A M Singhvi when CJI Dipak Misra, while heading a constitution bench, permitted him to mention a petition challenging arrest of five rights activists. The CJI went out of the way to list the matter same day, constituted a bench and heard it after scheduled court hours.

In contrast, whenever advocate Mathews J Nedumpara attempts to mention or argue a petition, the bench’s irritation is palpable. True, he does not possess the stature or skills of renowned lawyers and may have a repetitive dissenting note to his arguments. There are many like him who are not endowed with the brilliance of successful lawyers. Their dissent needs to be addressed too. We hope they too get a patient hearing after Justice Chandrachud’s vitalising comment that dissent is intrinsic to democracy.

Famous contempt cases

1994-2017

From: Dhananjay Mahapatra, Furious SC makes ex-CBI chief ‘sit in a corner till court rises’, February 13, 2019: The Times of India

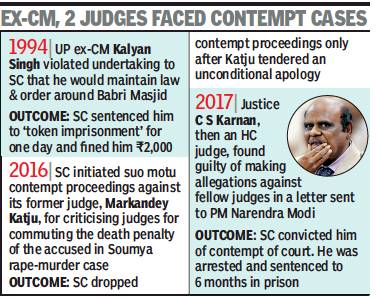

See graphic:

Famous contempt cases, 1994-2017

Judge vs. judge

When a judge alleges bias on the part of another

After retiring from the Supreme Court, Justice Kurian Joseph explained why he went with three senior SC judges — Justices J Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi and Madan B Lokur — to address an unprecedented press conference on January 12. He said all four shared a perception that then CJI Dipak Misra was being influenced by someone from outside and was allotting sensitive cases to benches headed by select junior SC judges perceived to have a political bias.

Coming from a seasoned judge like Justice Joseph, the charges were serious. He was imputing motives to two categories of judges — one, that CJI Misra was being influenced from outside; two, that some sitting SC judges harboured political bias while dealing with cases.

Can a commoner litigant, after his case gets dismissed, make similar allegations in public against the judge who decided his case and not get hauled up for contempt of court? Can a commoner dare make such perception-based allegations against sitting SC judges? Every day, a thousand perceptions run wild in the SC corridors. Lawyers discuss judges, their knowledge, demeanour, conduct,s judicial acumen and court behaviour. Howsoever strong their perception, no one dares to go public with their views on judges, for they know how choppy the contempt waters are.

Interestingly, a PIL has been filed in the SC seeking an inquiry into Justice Joseph’s statement about external influence on then CJI Misra. When it was mentioned for urgent hearing, CJI Ranjan Gogoi asked what the urgency for early listing was? The petitioner said “credibility of the institution is at stake”.

CJI Gogoi declined early hearing and said, “Credibility of an institution is best maintained by individuals who man it and not by newspaper reports.” It sounded similar to what Lord Dennings had said in R vs Commissioner of Police [1968 (2) QB 150].

Declining to initiate contempt proceedings against Quintin Hogg for his article in ‘Punch’, Lord Dennings had said, “Let me say at once that we will never use this jurisdiction to uphold our own dignity. That must rest on surer foundations. Nor will we use it to suppress those who

speak against us. We do not fear criticism, nor do we resent it. For there is something far more important at stake. It is no less than freedom of speech itself… All that we ask is those who criticise us should remember that, from the nature of our duties, we cannot reply to their criticism. We cannot enter into public controversy. We must rely on our conduct itself to be its own vindication.”

Lord Dennings’s approach stood the test of time in the famous ‘SpyCatcher’ case in 1987. Britain had banned publication of the book ‘SpyCatcher’ in the UK as a former MI5 agent Peter Wright narrated his experience in identifying a Soviet mole in MI5. Guardian newspaper got permission from UK High Court for reportage on ‘SpyCatcher’. But, the House of Lords, the predecessor of the UK Supreme Court, reversed the HC judgment [Attorney General vs Guardian newspaper 1987 (3) AER 316].

Next day, the ‘Daily Mirror’ newspaper ran a front page headline screaming ‘YOU FOOLS’ and accompanied it with upside down photographs of three law lords in wigs, who decided the case against reportage on ‘SpyCatcher’. No contempt was initiated. ‘The Economist’, which ran a blank page with a caption ‘law is an ass’, too was not visited with adverse consequences.

If Justice Joseph’s statement about ‘external influence’ on CJI Misra was based on perception and shared by the other three SC judges on January 12, similar was the case with Chandan Mitra, who as executive editor of Hindustan Times, wrote an article in September 1995 that “some Supreme Court judges needed psychiatric counselling”, reacting to the SC censuring Punjab Police in a famous case.

Unlike the Daily Mirror, Mitra was hauled up for contempt and in open court, then CJI J S Verma told him in 1996 that it was Mitra who needed psychiatric treatment, not the judges. Spooked by contempt powers, Mitra apologised profusely and published a front page apology to escape unhurt.

CPM leader M V Jayarajan was not as lucky as Hogg, Daily Mirror or even Mitra. The former Kannur MLA in November 2011 criticised Kerala HC judges for banning road meetings, and in his exuberance called the judges ‘sumbhan’, which roughly means ‘idiot’ in Malayalam.

The HC judges could not stomach the criticism and convicted him for contempt of court and punished him with six months imprisonment. On January 30, 2015, an SC bench headed by Justice Vikramjit Sen upheld the HC verdict, but was kind enough to reduce Jayarajan’s punishment to four weeks in jail.

On November 9, 1967, then Kerala chief minister EMS Namboodiripad in a press conference described the judiciary as “an instrument of oppression” and was hauled up for contempt of court. A bench headed by then CJI M Hidayatullah convicted him of contempt, but fined him Rs 50 [1970 AIR 2015].

On November 28, 1987, then law minister P Shiv Shankar at a Bar Council of India function in Hyderabad made a scurrilous statement, “Anti-social elements i.e. FERA violators, bride burners and a whole horde of reactionaries have found their heaven in the Supreme Court.”

Referring to Lord Dennings’s views in R vs Commissioner of Police, a bench led by then CJI Sabyasachi Mukharji had let off Shiv Shankar and had said the SC’s shoulders were broad enough to take criticism [1988 AIR 1208].

Would a commoner have been lucky like Namboodiripad or Shiv Shankar? Arundhati Roy would not agree. What exactly hurts judiciary’s sensitivity and credibility is difficult to discern from judgments of the SC. Who makes the ‘objectionable’ or ‘contemptuous’ remark probably holds the key to the action that could flow from the SC.

Lawyers: contempt by

Chaudhary, Nedumpara cases

Dhananjay Mahapatra, August 24, 2020: The Times of India

Minnows get minced, big guns go on trumpeting

Advocate-on-Record Prashant Bhushan’s conviction for contempt of court has drawn angst, dismay and opposition from retired judges, notably R M Lodha, Madan B Lokur and Kurian Joseph. Their support, along with that of “thousands of lawyers”, was flaunted by Bhushan’s counsel during the hearing on sentencing before a bench of Justices Arun Mishra, B R Gavai and Krishna Murari.

Bhushan’s ilk, who project themselves as zealous protectors of right to free speech, seldom stood up for other advocates punished severely by the SC for much lesser crimes. Those advocates did not have the “you know who I am” credentials to flaunt. They were minnows who got minced in the contempt of court shredder without the ‘right to free speech’ brigade shedding a tear.

In the last three years [2017-20], advocate-on-record Mohit Chaudhary and lawyer Mathew Nedumpara were punished by the SC through suo motu contempt powers, which too has now been invoked against Bhushan. Pleadings of Chaudhary and Nedumpara and the punishments awarded to them by the SC did not stir a hair of Justices Lokur and Joseph, who were then sitting judges in the apex court.

In April 2017, Chaudhary had complained to a bench of then CJI J S Khehar and Justices D Y Chandrachud and Sanjay K Kaul that something fishy was going on in the SC Registry, which had listed a deleted matter. He also hinted at collusion between litigants and registry officials for ‘bench hunting’. Compared to what Bhushan got convicted for and what he has been saying and reiterating for the last 15 years, Chaudhary’s words were mere background music.

Hauled up for criminal contempt, Chaudhary tendered an apology. The bench was reluctant to accept it, finding hints of justification in what he had said. Chaudhary tendered an ‘unconditional apology’ again. When he was going through the nervewracking process, none of those reputed senior advocates who volunteered and signed resolutions for Bhushan made even a small noise for protection of right to free speech.

Those who sought mercy for Chaudhary included K K Venugopal, Salman Khurshid, R S Suri, Sidharth Luthra, Colin Gonsalves and Ajit Sinha. Forget support, the retired judges had no soothing word for him.

Two days after the Independence day celebrations in 2017, Justices Khehar, Chandrachud and Kaul said, “It was not an innocent act… but a well thought out decision to tread an unfortunate path which the existing Advocate-on-Record was unwilling to do… The allegations made against the Registry were false and there were innuendoes against the Court. The endeavour failed. Every action has to have an outcome. The contemnor thus must face some consequences of his conduct.” Chaudhary was debarred for a month from practicing as AoR in SC.

Last year, Nedumpara had questioned the process of designation of lawyers as ‘senior advocates’ by SC and alleged that it was conferred only on the kin of senior advocates and judges. While arguing before a bench headed by Justice R F Nariman, he took the name of senior advocate Fali S Nariman and repeated it despite warning from the bench. He was convicted for contempt.

On March 27 last year, a Justice Nariman-led bench punished him with a three-month jail term despite Nedumpara pleading never to repeat his mistake. The bench ordered: “We sentence Nedumpara to three months’ imprisonment which is, however, suspended only if Nedumpara continues in future to abide by the undertaking given to us today. In addition, Nedumpara is barred from practising as an advocate before the Supreme Court of India for a period of one year from today.”

Lower courts and contempt cases

SC bar on contempt cases in lower courts

AmitAnand Choudhary, Jan 03 2017, The Times of India

Sending out a clear signal to all subordinate courts,the Supreme Court held on Monday that no other court could initiate proceedings for contempt of the apex court.

Setting aside an order of the Delhi HC convicting senior journalists, printer and publisher of an English daily for a report on former Chief Justice of India YK Sabharwal, the court said the HC was not empowered to initiate proceedings and punish a person for contempt of the SC.

The HC had taken suo motu action after the news story was placed before it by advocate R K Anand.

In its order, Delhi HC had said that being a court of record, it can initiate proceedings for its contempt as well as contempt of its subordinate courts and also of the SC.

“The power to punish for contempt vested in a court of record under Article 215 does not, however, extend to punishing for the contempt of a superior court“ a bench of Chief Justice T S Thakur and Justice A M Khanwilkar said.

Mercy

Mercy when contemnor accepts mistake, apologises

AmitAnand.Choudhary , Dec 11, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi: Holding that mercy must remain an integral part of judicial conscience and courts should take a liberal approach when a contemnor accepts a mistake and apologises, Supreme Court quashed a Bombay HC order sentencing a woman to one week’s imprisonment for a contemptuous statement on the judiciary pertaining to stray dogs.

Quashing the jail term awarded to a former director of a residential complex in Navi Mumbai Seawoods Estates Ltd, a bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Sandeep Mehta said the HC should have accepted her apology. It said the statutory scheme recognises that once a contemnor expresses sincere remorse, even if the apology is not unqualified in form, the court is competent to accept it and, where necessary, discharge the contemnor or remit the sentence imposed.

“The power to punish necessarily carries within it the concomitant power to forgive, where the individual before the court demonstrates genuine remorse and repentance for the act that has brought him to this position. Therefore, in exercise of contempt jurisdiction, courts must remain conscious that this power is not a personal armour for judges, nor a sword to silence criticism. After all, it requires fortitude to acknowledge contrition for one’s lapse, and an even greater virtue to extend forgiveness to the erring. Mercy, therefore, must remain an integral part of the judicial conscience, to be extended where the contemnor sincerely acknowledges his lapse and seeks to atone for it,” SC said.

Though the apex court came to the conclusion that the circular issued by her was contemptuous, it let her off after noting that she promptly filed her reply in HC in which she explained the circumstances, expressed unconditional remorse for her conduct and tendered an unqualified apology at the earliest opportunity.

“The Explanation to Section 12 (of Contempt Act) further provides that an apology shall not be rejected merely because it is qualified or conditional, if offered bona fide. The scheme of Section 12(1) thus reflects a balance, ie while the majesty of law must be preserved against attempts to malign the institution and those discharging judicial functions, the provision also recognises human fallibility. It is for this reason that the proviso empowers the court, upon being satisfied of genuine remorse, to accept the apology and discharge the contemnor or remit the punishment awarded,” the bench said.

The HC had taken suo motu cognizance after the circular was brought to its notice and proceedings were initiated after the residential society told the court it was not responsible for it. The woman had told HC that she had made a grave error in issuing the circular, which was done upon mental pressure exerted by residents. She further stated that she had also resigned from the board of directors of Seawoods.

“Therefore, in our considered view, HC failed to exercise its contempt jurisdiction with due circumspection. Once the contemnor had, from the very first day of her appearance in the suo motu proceedings, expressed remorse and tendered an unconditional apology, HC was required to examine whether such apology satisfied the statutory parameters under Section 12 of the Contempt Act. Thus, in our opinion, in the absence of any material suggesting that the apology was lacking in bona fides, HC ought to have considered remitting the sentence in accordance with law,” it said.

Misuse of power

Delhi HC apologises, awards relief to man sent to mental hospital by judge

The Delhi high court apologised to a 71-year-old man who spent 20 days in a mental health hospital on the orders of a judge hearing his accident case because he had lost his temper over the slow pace of the hearing.

The court also ordered the Delhi government to pay Rs 2 lakh as token compensation to the senior citizen.

“This court expresses its apology to Ram Kumar and his family members, including Ravinder (the petitioner), for the unlawful orders passed by the magistrate,” a bench of Justices S Muralidhar and I S Mehta observed, adding that Kumar, “a heart patient, was subject to tremendous stress on account of his illegal confinement at Institute of Human Behaviour and Allied Sciences (IHBAS). In short, there was a cascade of violations that had a domino effect on Kumar, denuding him of his rights to life, liberty, dignity and privacy”.

Taking a grim view of recurring instances of persons being taken illegally to mental health hospitals, the HC ordered the legal services authority to “conduct a survey of mental health institutions and facilities in Delhi to ascertain how many inmates are being illegally held, in violation of the Mental Healthcare Act and the Constitution of India”.

In 2017, the court had quashed the magistrate’s order after Kumar’s distraught family filed a writ questioning his forcible confinement at the IHBAS.

Procedure

‘No one can be a judge in his own cause’

Judges cannot demand respect through contempt power: SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra The Times of India Nov 03 2014

Since its inception, the Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that “no one can be a judge in his own cause”. This principle brings fairness to the justice delivery system and upholds equality of all before law.

It also lays down a sound ground rule for adjudication, decision and punishment. It bars anyone from becoming a complainant, investigator and also the judge, all rolled into one.

Against this backdrop, newspapers last week published an interesting news item. An MLA in Uttar Pradesh had barged into a school to slap a Class 5 student.

The boy allegedly had a brawl with the MLA’s son. Taking his son’s complaint against his classmate, the father took it upon himself to punish the alleged aggressor. Since he was the local MLA, he thought he had the sanction to punish the alleged wrongdoer. He executed the punishment without bothering to hear the classmate’s version of the story.

A similar story got enacted in Delhi High Court in Oct 2014. A magazine published a report alleging that an HC judge’s son had a stake in a hotel where the dance floor remained open much beyond the scheduled closure time.

It also alleged that police turned a blind eye because the stakeholder was an HC judge's son.

The publication came to the judge's notice. He inquired from his son, who told him that he had no connection with the hotel. On completing the inquiry with his son, the judge came to the conclusion that the report was published to tarnish his image and also to bring disrepute to the judiciary .He also termed it an attempt to shake the public's confidence in judiciary , which would impede administration of justice.

He took up the case for hearing and issued contempt of court notice to the magazine's entire editorial staff, from the editor-inchief to the sub-editor and photographer. Importantly , he also directed the Delhi Police commission er to seize all copies of the magazine, which contained the `baseless' story, from its offices across the country.

These two incidents show that aberrations continue despite repeated pronouncements by the SC cautioning everyone, including judges of the higher judiciary , against donning the dangerous `judge in his own cause' robe.

In 2010, the apex court in Mohd Yunus Khan vs UP had referred to its own judgments in A U Kureshi vs High Court of Gujarat [2009 (11) SCC 84] and Ashok Kumar Yadav vs State of Haryana [1985 (4) SCC 417]. In both, the court had held that no person should adjudicate a dispute in which he or she has dealt with in any capacity .

“The failure to observe this principle creates an apprehension of bias on the part of the said person. Therefore, law requires that a person should not decide a case wherein he is interested.The question is not whether the person is actually biased but whether the circumstances are such as to create a reasonable apprehension in the minds of others that there is a likelihood of bias affecting the decision,“ it had said in the 2010 judgment.

More than 60 years ago, the Supreme Court had laid down the parameters for contempt of court proceedings in Rizwan-ul-Hasan vs Uttar Pra desh [1953 SCR 581].

It had said, “The jurisdiction in contempt of court is not to be invoked unless there is real prejudice which can be regarded as a substantial interference with the due course of justice. The purport of this court's action is a practical purpose and the court will not exercise its jurisdiction upon a mere question of propriety .“

In 2007, the court in Rajesh Kumar Singh vs High Court of Madhya Pradesh had elaborated and expanded the contempt ground rule laid down in 1953.

It had said, “This court has repeatedly cautioned that the pow er to punish for contempt is not intended to be invoked or exercised routinely or mechanically , but with circumspection and restraint. Courts should not readily infer an intention to scandalize courts or lower the authority of court unless such intention is clearly established. Nor should they exercise power to punish for contempt where mere question of propriety is involved.“

Expressing anguish at the invocation of contempt jurisdiction by some judges at the drop of a hat, the court had said, “Of late, a perception that is slowly gaining ground among public is that sometimes, some judges are showing over-sensitiveness with a tendency to treat even technical violations or unintended acts as contempt. It is possible that it is done to uphold the majesty of courts, and to command respect.“

What it then said is worth its weight in gold. “Judges, like everyone else, will have to earn respect. They cannot demand respect by demonstration of power. Nearly two centuries ago, Justice John Marshall of US Supreme Court had warned that the power of judiciary lies not in deciding cases, not in imposing of sentences, not in punishing for contempt, but in the trust, confidence and faith of the common man.“

Truth as a defence

Must meet criteria of “bona fide + public interest”

NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court said that right to free speech was no licence to derogate the judiciary and denigrate judges but agreed that truth was a valid defence against contempt of court offence if it met the twin criteria of “bona fide and in public interest”.

Rejecting activist-advocate Prashant Bhushan’s defence that his tweets were his bona fide opinions forming part of his right to free speech, which could not be regarded as contemptuous, a bench of Justices Arun Mishra, B R Gavai and Krishna Murari said: “That free speech is essential to democracy cannot be disputed but it cannot (be used to) denigrate one of the institutions of democracy.

“No doubt, one is free to form an opinion and make fair criticism but if such an opinion is scandalous and malicious, the public expression of the same would also be at the risk of contempt jurisdiction. It cannot be forgotten that rights under Article 19(1) are subject to reasonable restrictions under Article 19(2) and rights of others cannot be infringed in the process. The same has to be balanced.”

On freedom of press, the bench said that it was an important aspect of democracy. “We cannot control the thinking process and words operating in the mind of one individual, but when it comes to expression, it has to be within constitutional limits.”

Referring to Bhushan’s remarks, the bench said: “Lawyers’ noble profession will lose all its significance and charm and dignity if lawyers are permitted to make any malicious, scandalous and scurrilous allegations against the institution of which they are a part. Lawyers are supposed to be fearlessly independent and robust but at the same time respectful to the institution.”

The SC added: “If a scathing attack is made on judges, it would become difficult for them to work fearlessly and with the objectivity of approach to issues. The judgment can be criticised. However, motives to the judges need not be attributed, as it brings administration of justice into disrepute.”

Responding to the argument that Bhushan, in his 35-year career, had made a huge contribution to society through PILs in the SC, the bench said: “Merely because a lawyer is involved in the filing of PIL for the public good does not arm him to harm the very system of which he is a part. It cannot be said that a person who is a lawyer having 35 years’ standing, who has made malicious and scandalous comments in tweets and amplified them by the averments made in the affidavit in reply which have the effect of denigrating the very institution to which he belongs, can be made honestly or in good faith.”

The bench said for considering truth as valid defence, it must meet two requirements. “The sine qua non for considering truth as a valid defence are that the court should be satisfied that defence is in the public interest and the request for invoking the said defence is bona fide,” it said.

“We are of the considered view that the defence taken is neither in public interest nor bona fide, but the contemnor has indulged in making reckless allegations against the institution of administration of justice. As referred by the attorney general, the averments are based on political consideration, and therefore in our view cannot be considered to support the case of the contemnor of truth as a defence. The allegations made are scandalous and are capable of shaking the very edifice of judicial administration and also shaking the faith of the common man in the administration of justice,” the bench added.